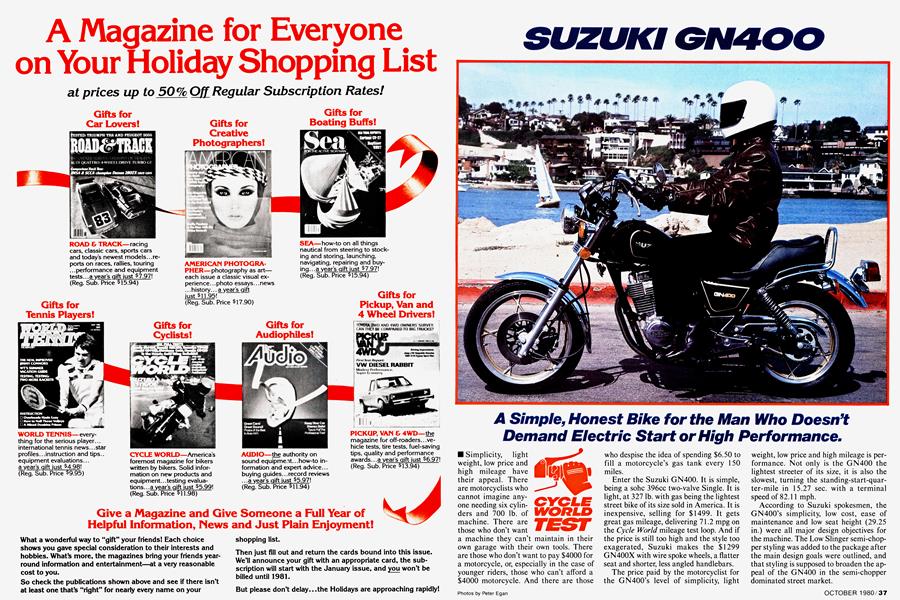

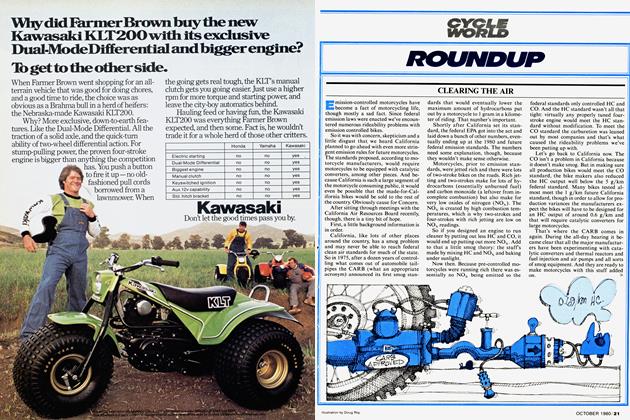

SUZUKI GN400

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A Simple, Honest Bike for the Man Who Doesn't Demand Electric Start or High Performance.

Simplicity, light weight, low price and high mileage have their appeal. There are motorcyclists who cannot imagine anyone needing six cylinders and 700 lb. of machine. There are those who don't want a machine they can't maintain in their own garage with their own tools. There are those who don't want to pay $4000 for a motorcycle, or, especially in the case of younger riders, those who can't afford a $4000 motorcycle. And there are those who despise the idea of spending $6.50 to fill a motorcycle’s gas tank every 150 miles.

Enter the Suzuki GN400. It is simple, being a sohc 396cc two-valve Single. It is light, at 327 lb. with gas being the lightest street bike of its size sold in America. It is inexpensive, selling for $1499. It gets great gas mileage, delivering 71.2 mpg on the Cycle World mileage test loop. And if the price is still too high and the style too exagerated, Suzuki makes the $1299 GN400X with wire spoke wheels, a flatter seat and shorter, less angled handlebars.

The price paid by the motorcyclist for the GN400’s level of simplicity, light

weight, low price and high mileage is performance. Not only is the GN400 the lightest Streeter of its size, it is also the slowest, turning the standing-start-quarter-mile in 15.27 sec. with a terminal speed of 82.11 mph.

According to Suzuki spokesmen, the GN400’s simplicity, low cost, ease of maintenance and low seat height (29.25 in.) were all major design objectives for the machine. The Low Slinger semi-chopper styling was added to the package after the main design goals were outlined, and that styling is supposed to broaden the appeal of the GN400 in the semi-chopper dominated street market.

Fair enough. More puzzling is Suzuki’s contention that the GN400 is equally suited for beginning, first-time motorcycle buyers and experienced enthusiasts as well.

We can understand the appeal to some long-time enthusiasts, like the man with 24 years riding experience who wrote to say that he found the GN400 ideal for “a maturing person like myself who no longer gives a damn about having his arms pulled out of their sockets but likes ease of maintenance, simplicity and just taking a real nice bike out on a back country road.”

But in the quest for low cost and light weight, Suzuki engineers left off the electric starter usually found on beginner’s bikes. The GN400 has a kick-starter only. More on that later.

The GN powerplant is the same as found in the DR and SP400s, and that motor started life in the SP370. A 3mm overbore gave the engine its current displacement of 396cc. Compression ratio is 9.2:1. Its two valves are operated by rocker arms/cam followers riding on the sohc. Cam drive is conventional roller chain. The crankshaft has roller bearings, and primary drive is by helical gear direct to the clutch. The transmission has five speeds.

Ignition is a CDI magneto, with additional mag coils charging the battery and powering the headlight. The tiny 6 volt battery has a 4 ampere hour rating and powers only the taillight, turn signals, instrument lights and horn. Because the headlight is directly powered off the magneto, it only operates when the engine is running. The electronic ignition system has no points and requires no maintenance.

The GN’s ignition and lighting system is the same as used on the dual-purpose SP400, and contributes to the GN’s light weight—a system using only batterypowered lights and ignition would require a bigger, heavier battery.

The GN has a 36mm Mikuni CV carburetor, which makes it pretty difficult for even an inexperienced rider to stall the engine when underway. Incorporated into the carburetor is a deceleration valve designed to riehen the mixture and prevent backfiring if the rider slams the throttle shut at high rpm. Without such a valve, the instantaneous leaning of the mixture when the throttle was closed would prevent the mixture from firing in the combustion chamber. Instead, the unburned fuel would accumulate in the muffler until it was exploded by hot exhaust gases from the next cycle that did fire in the combustion chamber. That phenomenon is why the SR500, for example, spits and backfires when the throttle is abruptly closed while approaching a signal or simply slowing down.

Our test GN400 developed an exhaust leak where the head pipe joins the muffler and started backfiring and spitting when

slowing, in spite of the deceleration valve. And because the EPA carburetion is very lean at small throttle openings, the GN400 will stall leaving a signal unless the rider grabs enough throttle to get past the lean spot, which, of course, results in higher rpm starts. If low-end torque is judged by the ability to move away at low rpm, the GN400 has less torque than any of the 400cc-class four-stroke Twins. Unfortunately, the popularly-held belief that Singles have a torque advantage over Twins or Fours isn’t always applicable, depending upon many factors, including cam timing and lift, valve sizes, carburetion and exhaust tuning.

Overall, however, the GN400 carburâtes better than many other 1980 Suzukis we’ve ridden, particularly when cold. Which brings us to the choke and coldstarting. Specifically, the location of the choke, on the left side of the carburetor, hidden away under the gas tank.

This is a good bike for beginners, remember? And maybe beginners don’t know any better, but locating the choke on the carb is inconvenient. The reason it is there, of course, is to hold down the retail price.

And then there’s the kick starting. To make it easier, Suzuki engineers have come up with an ingenious compression release system. The rider puts the bike on the centerstand, pulls in the compression release lever (located near the clutch lever on the left handlebar), and takes his fingers off the compression release lever. The lever stays depressed indicating the exhaust valve is being held open. The rider slowly pushes the kick start lever until the compression release lever snaps closed, which means that the rocker arm has started to open the exhaust valve and that the piston is in the best position for easy starting. The rider lets the kick start lever return to its top position, gives it a strong kick, and the engine should start.

Using that method and giving the engine choke and one-eighth throttle when cold and no choke with one-eighth throttle when hot, the GN400 usually started on the first kick, even for a 98-lb. woman we recruited to test the system’s applicability for beginners.

The biggest problem for beginners may be that they don’t give the lever enough of a kick, or that they don’t follow the directions. If they are willing to follow the instructions, they won’t have any problems.

This may be mostly a matter of definitions, i.e. who are these beginning riders and what do they expect the motorcycle to do?

All the major dual-purpose Singles, two-stroke or four, come with kick only and nobody wonders at that, because bikes with off-road potential are expected to appeal to a more sporting crowd that appreciates light weight and simplicity. Honda uses kick only on the CB125, which doesn’t need any other devices. Kawasaki and Yamaha provide electric legs for their street 250s and Yamaha at least makes it plain they don’t think new riders want to kick, or even to learn about anything beyond the little black button. And Honda and Yamaha provide automatic assistance for their compression releases, via lifters linked to the kick lever.

So here’s the Suzuki GN400 and it’s a largish Single and can use the compression release fitted. But, the rider must use it, on purpose, and that’s one more thing to learn, which may mean the GN400 only appeals to people who like mechanical devices, want the light weight and simplicity and low seat height and don’t want a dirtpotential motorcycle. At the same time Suzuki has covered its bets with the GS250 Twin, electric start and everything, for a little more performance, weight and money. All very interesting, and we’ll how to wait for the sales report to see just who many people want what.

Once running, the GN400 would stay running, without giving the rider any worry of having the engine stall while waiting at an intersection, requiring a kick-restart in the middle of traffic. (Anybody who used to ride old British Singles with Amal carbs can relate to that particular trauma).

And the GN400 got excellent gas mileage, even when ridden way over the speed limit. As mentioned before, the GN delivered 71.2 mpg over the standard two laps of the 50-mile Cycle World mileage test loop, incorporating city traffic, country roads and interstate highway, with the bike ridden at close-to-legal speeds. In constant stop-and-go commuting the bike would achieve 63 mpg, and full-throttletop-speed open-country-road jaunts moderated with some freeway riding on the same tankful still produced over 55 mpg.

Like all Singles, the GN400 vibrates and it vibrates more than Twins of the same displacement. But while the mirrors

blurr slightly on the highway and the front end shakes at idle, the GN’s vibration levels are not so high to cause rider discomfort. The rider can feel the buzz through the seat and pegs at speed, but the rubbermounted handlebars do a good job of controlling vibration at the grips. Now, it isn’t electric-motor smooth, but on the other hand there is no way the rider will forget he’s on a machine, a pulsing, working motorcycle.

The rider may wish he could forget he was sitting on the GN400 seat, which outdoes the 1980 Honda Hawk for the worstseat-on-a-small-bike championship. The GN’s seat is hard, shaped wrong and generally miserable. About the best thing that can be said about the seat is that it is light, since the seat base is plastic. Seating position in relationship to handlebars and pegs was all wrong for our usual riders, (ranging from 5-ft-10 to 6-ft.-2) riders, but we must admit that the seat height was a big hit with the woman we recruited to test the viability of the kick starting system for beginning riders.

Standing a bit over five feet tall, our volunteer woman loved the GN compared to her own Honda CM 185, which she bought because it was the only 1979 street bike that allowed her to firmly plant both feet on the ground at a stop sign. The GN’s seat was low enough for her to touch down, as well, and she liked the additional power. She loved the styling and the digital gear indicator, too.

One look at the frame shows that Suzuki engineers took extra pains to get the seat height low. And they did a pretty good job of building suspension compliance into an economy bike, the GN’s forks and laid-down shocks performing well on repetitive small bumps and larger jolts, too.

It’s unlikely that buyers of the GN400 will run it as hard as we did during the high-speed part of our testing. But if they do, they’ll find that the GN, as to be expected from such a light bike, changes direction rapidly, whether from rider input or pavement irregularities or sidewinds. It

turns well enough, although the head pipe and muffler join the footpeg in scraping on the right side (the footpeg and stands touch on the left) during spirited riding. And while the GN has trouble pegging its 85-mph speedometer even with the rider fully tucked in, there is a hint of wander in the front end in top-speed sweeping turns.

What we mean is that the rider gets the distinct feeling that if he isn’t careful, if he makes one fast move or demands that the bike change direction or even if he runs over a big bump or pebble or dip that the GN’s front wheel will do something drastic, like wash out.

It didn’t, and nothing awful happened to our test riders, but the bike does give that impression.

The fault could lie in one or both of two areas. First, the tires on an econo-bike can be expected to be, naturally, econo-tires. Which means inexpensive with acceptable grip for econo-riding, i.e., not backroadblitzing.

Second, the GN has an unusual combination of lots of rake (29.5°) and not much trail (4.06 in.) which may be designed to complement style (giving the impression of an extended front end) while maintaining easy slow-speed manueverability.

The result is that disconcerting feedback through the bars at speed, a feeling that discourages twisty-road charging. Only experimenting with better tires would determine whether the front end uncertainty could be easily cured.

Even if the GN didn’t have that handling strangeness, we doubt that anybody would try any fast riding after sunset. The lighting system, again designed for light weight, won’t win any awards for excellent road illumination. The lights meet legal requirements and are acceptable for speed-limit riding on well-lit roads or sedate riding on un-lit country roads.

Perhaps the best judge of the GN400 are the people likely to be drawn to it on the dealer’s floor, people willing (or able) to spend just so much money, people who have trouble touching the ground on other bikes, people who don’t want any more weight in a machine than necessary.

Maybe the best reflection of the reaction of those people to the GN400 is the fact that the woman with the CM 185 came back from riding the GN400 full of praise and enthusiasm. “How much does one of these cost?’’ she asked. You could see her bank balance being figured in her head, and if a salesman had been present she would have written a check on the spot.

If the horsepower wars no longer excite you, if maintenance bills for multis are too high for you to tolerate, if wrestling a big bike around your garage floor has lost its appeal, if you need a low seat, if you’re just beginning and are looking for an inexpensive bike, then by all means consider the GN400. S

SUZUKI

GN400

$1499