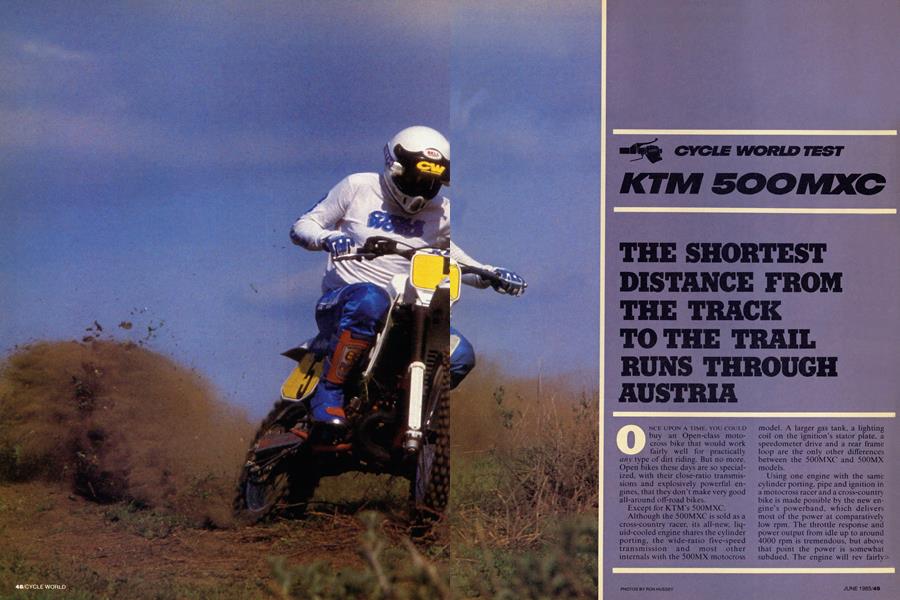

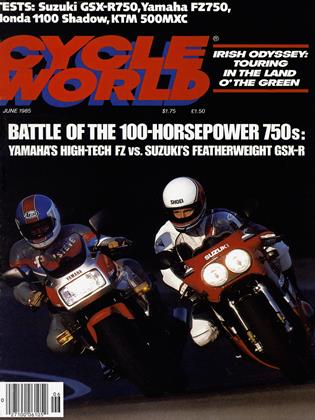

KTM 500MXC

CYCLE WORLD TEST

THE SHORTEST DISTANCE FROM THE TRACK TO THE TRAIL RUNS THROUGH AUSTRIA

ONCE UPON A TIME, YOU COULD buy an Open-class motocross bike that would work fairly well for practically any type of dirt riding. But no more. Open bikes these days are so specialized, with their close-ratio transmissions and explosively powerful engines, that they don’t make very good all-around off-road bikes.

Except for KTM’s 500MXC. Although the 500MXC is sold as a cross-country racer, its all-new, liquid-cooled engine shares the cylinder porting, the wide-ratio five-speed transmission and most other internals with the 500MX motocross

model. A larger gas tank, a lighting coil on the ignition’s stator plate, a speedometer drive and a rear frame loop are the only other differences between the 500MXC and 500MX models.

Using one engine with the same cylinder porting, pipe and ignition in a motocross racer and a cross-country bike is made possible by the new engine’s powerband, which delivers most of the power at comparatively low rpm. The throttle response and power output from idle up to around 4000 rpm is tremendous, but above that point the power is somewhat subdued. The engine will rev fairly> high, but little power is produced once it’s past that 4000-rpm mark.

SHORT-SHIFTING I WINDING THE ENG PRODUCES LOTS 0' LITTLE IN THE WA ANDATORY; : TIGHTLY FOISE BUT F ADDED SPEED.

With so much power concentrated at low engine revolutions, short-shifting is mandatory; winding the engine tightly produces lots of noise but little in the way of added speed. Stay down in the lower rpm ranges, though, and the KTM is torquey and tractable—and fast.

Because the engine has so much low-end and the overall gearing is so low, first gear is almost unusable for anything except crawling up nearvertical hills or negotiating ultra-tight woods. Starting in second or third gear, even in sand, is no problem with the standard gearing. So, to make better use of the five-speed gearbox and the low-rpm powerband, and to provide higher top speed for desert-style cross-country riding, we replaced the stock 13-tooth countershaft sprocket with a 15-tooth sprocket. That, combined with the stock 48-tooth rear sprocket, made first gear more usable and upped the top speed from 76 mph to 89 mph. And for less wideopen riding, such as in not-too-tight woods and most motocross tracks, a 14-tooth countershaft sprocket offered the best compromise between speed and lugging ability. If the gearing is suited to the condi-

tions, the big 500 is as much fun to ride as any Open-class bike on the market. But there’s nothing fun at all about starting it. The kickstart lever is placed high on the left side of the engine, the internal mechanism engages when the lever is near the top of its arc, and tremendous force is required to spin the engine. So you can forget about kicking the lever through unless you use your entire body weight; simply stabbing at the lever with your leg won’t even move it. Luckily, one or two leaps on the lever is all it usually takes to get the engine going.

Once running, the engine rewards you for your kickstarting efforts by producing buckets of highly usable power, and by running more smoothly than any other Open-class motor we’ve ever tested. There’s no bothersome vibration anyplace in the entire rev range, and at certain rpm there is almost no vibration at all.

That’s no accident. The liquidcooled, 485cc engine in the 500MXC is all-new and designed to be smoother-running, even though it is very compact in size and, amazingly, 17 pounds lighter than the aircooled, 495cc motor it replaces. Compact center cases wrap around a new, larger-diameter crankshaft that, along with close attention to balancing, is responsible for the reduction in engine vibration. The 485’s bore is 3.3mm smaller (89mm vs. 92.3) than the 495 ’s, and the stroke is 4mm longer (78mm vs. 74); the cylinder is all-aluminum with a Nikasil bore surface. This electronically applied bore coating, which previously was used by KTM only on its 125cc and 250cc engines, reduces cylinder weight by two to three pounds, but it can’t be rebored; the cylinder can, however, be machined to accept a steel liner if disaster should strike.

These weight-saving measures in the engine are responsible for most of

the weight difference between the 500 and last year’s 495, because the rest of the bike is not significantly lighter. The chrome-moly steel frame is the same as used on KTM’s other 1985 250c and 500cc motocross and cross-country models, and has a 26.5degree steering head angle and 4.0 inches of trail. The rear subframe is detachable for easy servicing of the shock, and can be quickly removed by unscrewing four hardened bolts and two hose clamps. The 500’s extruded aluminum swingarm is about a half an inch longer than the 250’s, and is hard to fault until it’s time to adjust the chain: The rear axle nuts> are recessed into the arm, meaning that a socket is needed to loosen them. Any kind of open-end, boxend or adjustable wrench won’t fit. This is only a minor nuisance in the garage, but it’s a major aggravation out on the trail.

On the other hand, maintenance of the rear-suspension linkage that bolts to the swingarm has been made easier by the inclusion of grease fittings on the pivot points. Even the needle bearings on the swingarm pivot can be lubed through grease fittings. The Pro-Lever linkage also has revised geometry to provide a flatter progression curve for ’85, and the shock has adjustable compression and rebound damping.

Although the shock appears unchanged for '85, its internal damping rates are different. And, as in past years, the White Power shock has very tight internal clearances. This may be good for longevity, but the internal friction makes the ride brutal for the first 300 miles or so. After that break-in period the shock starts working so smoothly that it’s necessary to adjust the external compression and rebound damping knobs. We started the test with the compression set on its No. I (softest) position, and the rebound on No. 2. But once the shock was broken-in, the compression and rebound adjusters had to be notched up to their No. 3 settings, which provided a smooth, pleasant ride through the woods and in the desert. On the motocross tracks, setting No. 4 worked best for both compression and rebound.

White Power also makes the “upside-down” front fork that is standard on all '85 KTMs. Its compression and rebound damping are adjustable, but not externally; the fork must be disassembled and fitted with different shims to change the damping rates. Our bike’s fork was perfect as delivered, so we didn’t bother with the rather complicated, time-consuming job of changing the damping or the oil level. The triple-clamps are aluminum and have double bolts that securely hold the beefy, 54mm fork legs. The rubber-mounted handlebar pedestals are interconnected so they can move fore and aft but can't twist if subjected to a crash.

With a dry weight (all oils but no gas) of 229 pounds, the 500MXC is light for an Open-class cross-country bike. And it feels even lighter than it is. The quick steering geometry helps mask the long, 59.5-inch wheelbase when snaking through tight turns, yet the bike easily lofts the front wheel over rocks and logs. Straight-line stability in high-speed sandwashes is excellent, and there’s no headshake or wobble. Sliding fireroads takes a little practice, though, because the back of the 500 will quickly pass the front if the rider isn’t very careful

Nothing gets in the way of the rider’s legs when standing on the pegs across whoops and such, for the KTM is narrow in the middle. The 3.1-gallon gas tank is placed low on the frame and is just barely wider than a motocross tank. The seat is fairly hard when new, but it’s not as firm as previous KTM seats and gets softer yet with use. By the time the bike has 400 or so miles on it, the seat has become quite comfortable.

The 500’s controls are well-placed, but the disc front brake and Magura throttle require more muscle to operate than those on most other Open bikes. The extra effort is especially noticeable when riding a tight enduro, for the rider’s right hand tires just from twisting the throttle and pulling the front brake. The same sort of complaint applies to the dual-leading-shoe rear brake: It requires a heavy push to operate, there’s little feel, and the engine can be easily stalled if the pedal is jabbed.

That sort of high-effort operation is fairly typical of KTMs, and so is a reputation for reliability. But our test KTM broke, and in a fairly big way: The kickstarter mechanism failed when the bike had approximately 500 miles on the it. The kick pedal would noisily move through its arc but wouldn’t turn the engine. The KTM people asked us not to disassemble the engine to diagnose the problem, but instead to give it back to them in exchange for a new one. So we didn’t see the damage for ourselves. But what apparently happened is that the engine backfired during kickstarting (which it easily can do, what with the aforementioned difficulty of kicking it through), and the lever flew back so violently that it broke the kickstarter stop inside the engine, destroying the engine cases in the process.

As with most off-road bikes, the 500MXC has no warranty, but KTM America representatives said that the company would, for a reasonable period of time, stand behind such an obvious defect. And they were not unfamiliar with the problem, either; we know of three other 1985 500MXCs that have suffered a similar failure and have had their engines replaced free of charge by KTM.

It’s admirable that KTM is so willing to back up its products, but the real problem is that the factory had not, as of this writing, effected a cure for this kickstarter failure. Thus, the replacement engines are just as likely to break their engine cases as the original ones. And unless a 500MXC owner is willing to change engines about as often as most riders change sparkplugs, KTM’s willingness to replace any broken motors is no solution at all.

That’s a tragedy. We really like the way the 500MXC performs, for it’s a rare bird in this day and age of specialization, a bike that can be competitive for motocross, enduros, desert racing or just plain trail riding. But until KTM comes up with a permanent cure for the kickstarter problem, we can’t heartily recommend that everyone go out and buy one. Potentially, it’s the niftiest all-around Open bike you can buy. But there’s one important qualification: You first have to get it running. S

KTM

500 MXC

$3077

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialCountering the Steering Myths

June 1985 By Pauldean -

At Large

At LargeInside the Accidental Fortress

June 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1985 -

Rounup

RounupLand Closure: the Fight For the Open Range

June 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupWave Bye-Bye To Street Hawk

June 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe World's Largest Gas Tank

June 1985