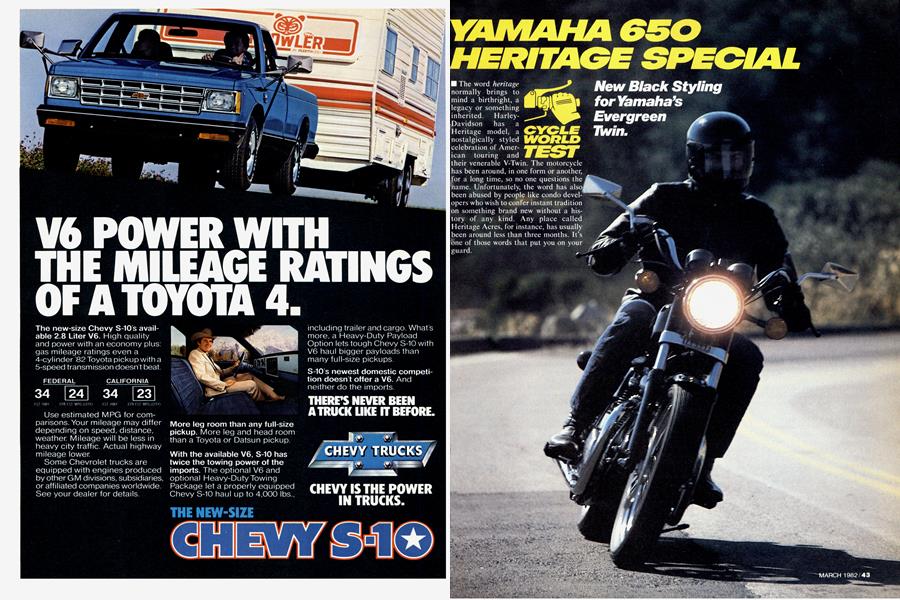

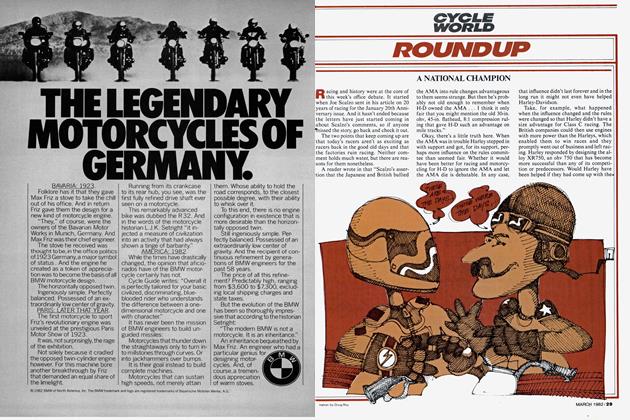

YAMAHA 650 HERITAGE SPECIAL

CYCLE WORLD TEST

New Black Styling for Yamaha's Evergreen Twin.

The word heritage normally brings to mind a birthright, a legacy or something inherited. HarleyDavidson has a Heritage model, a nostalgically styled celebration ol American touring and their venerable V-Twin. The motorcycle has been around, in one form or another, for a long time, so no one questions the name. Unfortunately, the word has also, been abused by people like condo developers who wish to confer instant tradition on something brand new without a history of any kind. Any place called Heritage Acres, for instance, has usually been around less than three months. It’s one of those words that put you on your guard.

In the case of the 1982 Yamaha XS650S, however, the Heritage title has also been legitimately earned. Yamaha’s big vertical Twin may not reach as far back as the Harley, but the XS650 has been with us now for 12 years, enjoying a model run of unusual length in the fast moving world of Japanese motorcycle development. In that time the bike has built up a loyal following, establishing a large owners’ club with a thick monthly newsletter and also making a name for itself as rival to the Harley XRs on the American flat track circuit. If that is not history enough, it can also be maintained that the XS650 inherited a bit of its design, image and no doubt a fair number of buyers from the traditional British Twin. In Japan, a part of its lineage also goes back to the Hosk, a 500cc vertical Twin from the Fifties, bought out by Yamaha in its early motorcycle days.

Whatever its inspiration, the XS650 has been a tremendous sales success for Yamaha over the years. Sales figures have reached McDonald-like proportions now, with over a quarter of a million sold. For several years during the Seventies, the XS650 was Yamaha’s biggest seller, even as late as 1978. Marketing people within the company still have a warm fondness for the durable Twin, and the bike’s popularity has kept it rolling off the assembly line, in various forms, right up to the present.

Cynics might ask (and occasionally do) how a vibration-prone vertical Twin with no counterbalancer, considerably less performance than the average 550 Four and only a single overhead cam can continue to sell in this age of multis, turbos, computers and digital everything. The answer, of course, is partially contained within the question. There are still a lot of motorcyclists who prefer their machines to be as simple and straightforward as possible, and there will probably always be a certain number of buyers who prefer the sound and feel of a pulsing Twin to the more electric smoothness and whirr of a multi. Not all Twins are alike, of course, and the Yamaha is a mixed bag of the advantages and disadvantages that go with the genre.

While the XS650 is often compared with British Twins of the past—and present—it differs from the BSA, Norton and Triumph designs in having a single overhead camshaft, chain driven, rather than one or two gear driven camshafts in the upper engine cases and pushrod valve actuation. The Yamaha’s overhead cam rides on two pairs of single-row ball bearings in the cylinder head and the cam lobes act directly on the rocker arms. The rocker arms pivot in a removable casting that also forms the upper half of the camshaft bearing support shell. The cam is driven by a single-row roller chain between the cylinders.

Another departure from earlier vertical Twin designs is the bore and stroke configuration of the Yamaha, 75 x 74mm, making it just barely oversquare, compared with the severely undersquare,, long-stroke Twins from England. Even the current Triumph Bonneville, bored out to 750 from an original 650, has a bore and stroke of 76 x 82mm. The Yamaha, therefore, has lower piston speed at a given rpm and, all other things being equal, better piston and bore life and a higher redline. The Yamaha uses aluminum pistons, slightly domed and relieved for valve clearance. The alloy barrels have iron cylinder liners, and the head and barrels are held together with fulllength studs extending upward from the cases. The cases themselves follow modern Japanese practice, being split horizontally rather than vertically, changing the age-old vertical Twin tradition of leaving small pools of oil wherever the bike is parked.

The 650’s 360° crankshaft is supported by four main bearings, with roller bearings on the timing side and the two center mains and a ball bearing cage on the drive side. Caged roller bearings are also used on the big ends of the connecting rods and the small ends have caged needle bearings. Rather than one or two large flywheels, the Yamaha uses four small ones, two flanking each connecting rod on the crank. The crank drives the clutch via straight cut gears. Overall, the bottom and top ends of the motor are robust and solidly designed, leaving the 650 open for much of the high performance development work it has seen these past 12 years.

Maintenance tasks on the 650 are fairly simple and straightforward. The left cam cover, which used to house the contact points and advance unit, is. now empty. The non-adjustable trigger for the transistorized ignition is located opposite the generator brushes under the left case cover. The screw-and-locknut type valve adjusters under the four separate rocker covers can be easily adjusted by the home mechanic, though the owner’s manual recommends that both valves and cam chain be adjusted by an authorized dealer and the book provides no instruction for doing either. This omission has become the rule rather than the exception in modern owner’s manuals, even on simple bikes like the XS650. The manufacturers are no doubt weary of warranty claims or lawsuits involving home maintenance mistakes (“After I adjusted my valves, Your Honor, the bike threw me right into a guard rail and I’d hardly been drinking at all. . .”) The twin air cleaner elements, one under each sidecover, are of a dry foam material and can be blown out with compressed air at cleaning time.

Carburetion on the 650 is handled by a pair of 34mm Mikuni CVs. The carbs are parallel to one another and linked by a common throttle shaft operated by a single pull-cable from the twist grip. The choke, or more accurately, the enrichening tubes, are controlled by a thumb lever at the left handgrip.

In an era of air forks, monoshocks and multi-adjustable damping the XS650’s suspension is also dead simple. The rear shocks offer four preload positions for the springs, period, and the front legs each have a preload screw under a rubber cap at the top of the leg. Normally these screws can be cammed downward with a screwdriver, stopping at two or three detent positions for increased amounts of spring preload. On our test bike, however, the adjusting screws turned but would not lock down, always snapping back into > the upper position. In effect, they didn’t work, so we were unable to experiment with front suspension settings. In any case, the forks worked well for normal street riding in the lowest setting, though people who install large fairings or other touring weight will probably want the extra preload.

The first XS650s were not good handling bikes; in fact very soon after their release they developed a reputation for wobbling and doing other strange things in corners. In the early Seventies Yamaha revised the frame and made substantial improvements in the bike’s overall stability. Since that time, a great many other Japanese bikes have made great leaps forward in handling—so much so that the XS650 now feels a bit strange by comparison. It does nothing unsafe or nasty, but has a resistance to being turned that often causes the bike to run slightly wider in the exit of a corner than the rider intended. Once the rider adjusts to this trait he can make the bike go where he wants, but fast riding takes more concentration with the XS650 than it does with more neutral steering bikes, like Yamaha’s own 550 Seca. The bike never becomes truly comfortable at higher speeds. The awkward handlebars, their length badly out of proportion to the shortness of the bike, accentuate the problem, as does the confining stepped seat.

With its pullback bars, styled seat, fat rear tire and black-on-black paint scheme, however, the 1982 650 is clearly not aimed at the canyon racer and peg scraping crowd, who have plenty of other good bikes these days (several of them made by Yamaha) to keep them happy. Ergonomics, as much as styling, dictates that the bike and its owners will be more content in an urban setting than out on the highway. Any long riding stint at highway speeds is tiring on the 650, as the rider is forced to brace himself against the wind from a bolt upright seating position. Hard on the back and elbows. A full day on the road will leave the owner wishing he’d bought the understated and much more comfortable “standard” version of this bike we tested in 1979. Progress is a funny thing.

One thing progress hasn’t changed is the sound and feel of the large vertical Twin. When first started up in the morning on full choke, the 650 is subdued enough to warm up and get out of the immediate neighborhood without shaking windows or annoying anyone. But when accelerating up to speed or cruising at normal rpm the engine puts out a nice deep burble, always pleasantly audible but never bothersome. The engine works best between 3500 and 6000 rpm. Within that range the engine provides instant, strong throttle response with no carb hesitation or flat spots. The engine also works well below 3500 rpm, but has less flywheel effect coming off the line than we’ve come to expect from most larger Twins and doesn’t really start to pull at the arms until revs build. Above 6000 rpm the lack of counterbalancer (or a couple of extra cylinders) makes itself known and the handlebars and footpegs develop a healthy level of vibration. Fortunately, there is little need to run the engine to redline, as it pulls like a tractor through its entire midrange and it’s possible to ride the bike quickly without ever twisting the tach needle much beyond 5000 rpm. Engine speed at 60 mph is 4206 rpm, so at anything within 20 mph of a reasonable highway speed the 650 is running at its smooth, well-mannered best, which is the way it should be, to borrow Yamaha’s own slogan. Highway cruising is relaxed (for the engine) and relatively smooth up to about 70 mph, where vibration begins to intrude again.

Lack of flywheel effect, along with a fairly high first gear makes the XS650 harder to get off the line smoothly than most other big Twins. First gear feels almost as though it should be second, so it takes some clutch slippage to get the bike rolling before the rear tire catches up with the engine and the two can be solidly hooked up. This isn’t much of a problem once the bike is fully warmed up (after about five minutes of riding) but makes it easy to bog and stumble when taking off from a stoplight with the choke still partially on. After first gear the ratios seem tighter than they need to be on a bike with such a cheerfully wide powerband, so if we could wave our magic ratio wand over the gearbox we’d specify a lower low, a wider spread and maybe even a slightly higher high gear.

One thing everyone noticed about the XS650 engine was how little mechanical noise it makes at idle, especially compared with some of the older pushrod vertical Twins that made enough clanking, tapping and whirring noises to worry a whole roomful of people, even when everything was properly adjusted. The Yamaha idles quietly and confidently. Part of this quiet has been achieved by eliminating clutch rattle, in turn made possible by tighter tolerances between the plates and friction discs. This keeps the noise down, but also creates just enough clutch drag to make for sticky shifting, particularly on downshift. It occasionally makes a second dab at the gear lever, and a firm one at that, to change gears. This may be a condition that will loosen up and improve as the miles are piled on, but on our new test bike shifting was notchy.

When our bike was delivered the idle was set at about 900 rpm, which made for a nice relaxed loping idle but allowed the engine to die any time the brakes were used with the throttle closed. We set the idle up to the 1200 rpm recommended on the emissions/tune-up sticker under the seat, which mostly solved the problem. But even with the idle set up our test bike would occasionally spit back and die at stoplights. The electric starter, of course, makes this an only momentary inconvenience, not like in the kickstart-only days when men were men and long lines of cars would honk while you tried to restart your stalled Twin. And, of all blessings, the Yamaha also comes with a real kickstarter, so if your battery runs a little low you are also spared the rigors of a runand-bump start.

The single front disc and rear drum on the XS haul the bike down in 36 ft. from 30 mph and 138 ft. from 60 mph, neither impressive nor too bad for a bike with the Yamaha’s 474 lb. The 650, however, demands fairly high lever pressure in both low and high speed stops and the front brake lever has a vague, mushy feel that didn’t endear it to any of the test riders. One rider, who climbed off the Yamaha and traded for a Suzuki GS650 (admittedly a bike with dual front discs) on a weekend ride commented that after building up his grip on the Yamaha he almost threw himself over the Suzuki handlebars the first time he used the brakes. In short, the XS650’s brakes work okay but are not quite up to the best current standards in feel and leverage.

At the drag strip the XS650 ran through the quarter-mile in 14.01 sec. at 93.26 mph, which makes it a little quicker and faster than the first XS650 we tested in 1970 (14.23 sec. at 93.26 mph) and just a hair off the pace of our 1979 test bike (13.86 sec. at 96.05 mph). Interestingly, all three had a top speed of 105 mph in the half mile. The XS650’s drag strip performance makes it quicker and faster than that other vertical Twin in town, the Triumph 750 Bonneville (though the Bonneville, with its larger flywheels, gets off the line a little better) and puts it roughly on a par with the BMW R65 (13.99 sec. at 93.16 mph). In all-out performance the XS650 ís simply not in the hunt with the current lineup of 650 Fours and most 550 Fours, but then the drag strip and road racing course are not really the Heritage’s venue. In the everyday world of street riding, the Yamaha’s power and speed are more than adequate, even two-up. Tuning a lot more upper end performance into the Twin would only interfere with its nice, useful powerband and tractability.

At the end of the usual CW mileage test loop the 650 measured in at 56 mpg, which has become about the norm for mid-sized bikes in this era of EPA leanness and generally refined cylinder head design. This is also the era of fewer and more far-flung gas stations, so we regretted to note that the Heritage tank holds only 3.1 gal, when the very handsome tank on the discontinued standard model held 4 gal. The 140 mi. range to reserve is not bad, but it could be 50 mi. more, and was.

Instrumentation on the 650 is simple, lightweight, good looking, well-lighted at night and accurate. The headlight’s nice strong beam is a good compromise between reach and width. Sidestand placement is the worst since BMW invented bad sidestand placement; it’s right where you can’t see it, under the footpeg as you look down. We don’t have an old model to measure against, but the sidestand is probably right where it’s always been and the footpeg has been moved to accommodate the revised seating position.

While a few of the details of function have been looked to here and there on the 1982 XS650, the only changes of real substance on the new model have been in styling. The Heritage has a lot of black paint on it now—carbs, head and barrels, handlebar cover, headlight shell, front fender, fork legs, taillight bracket and turn signal shells—all are black. Thankfully, the trim is silver (people discovered that black and gold looked nice together on the John Player Lotus and Norton Commandos a few years back and the world is now reeling from things black and gold). The cooling fins on the engine have been rounded off and the edges of the fins polished to contrast with the black engine. The bike has a stepped seat, pullback bars, shorty mufflers, a fat rear tire and a small gas tank. The front wire wheel has 64 small spokes rather than 32 big ones, and the sidecover emblem that used to say OHC 650 in block letters now says Heritage Special in greeting card script.

Is the XS650 a better bike?

Only if you like the way it looks now better than the way it used to look. If you do, the bike is good enough that the upright riding position and small tank won’t be discouraging. If you liked the old standard model better, you will feel that a certain amount of comfort and practicality has been given up to get the Heritage look.

In either case, the bike underneath it all is a solid, proven machine. Our Owner Survey in June, 1980, showed that, barring dead batteries due to the easily-replaced generator brushes wearing out, the Yamaha 650 was one of the most reliable bikes on the road. The bike produced a largely contented group of owners, and a high 73 per cent said they would buy another XS650. They were also in general agreement that the look and sound, and the relative simplicity, of the 650 Twin were what motorcycling is all about.

By comparison with more recent designs, the Heritage Special shows how far we’ve come in polishing the small, rough edges off our motorcycles. And at the same time it provides enjoyment for people who also appreciate where we’ve been and like an element of tradition in their motorcycling.

And more than that, the XS650 lists for only $2299, a very good price when many 650s are pushing toward, and over, the $3000 mark. Like another long running machine, the Model T Ford, the XS650 has managed to remain accessible and inexpensive as a consequence of its own popularity.

YAMAHA

650 HERITAGE SPECIAL

$2299