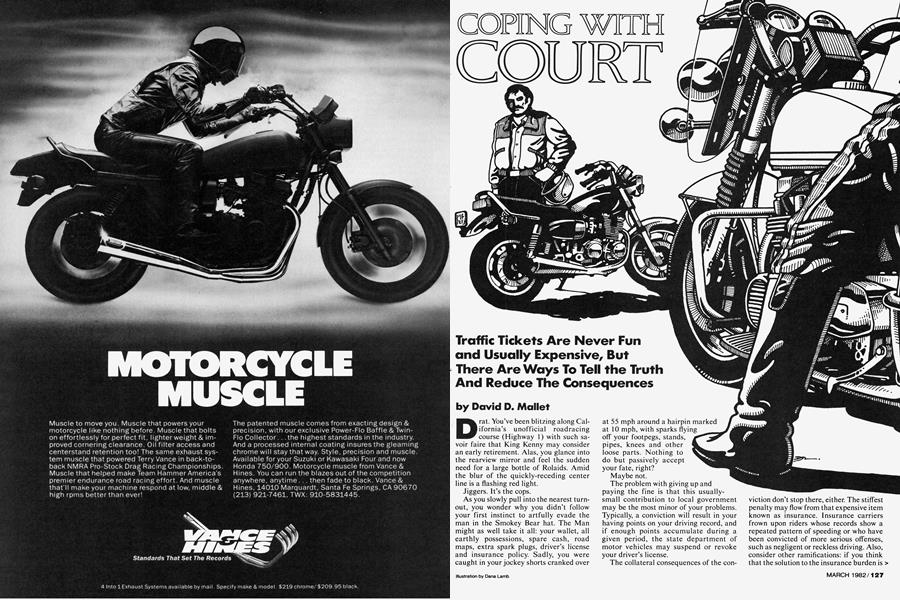

COPING WITH COURT

Traffic Tickets Are Never Fun and Usually Expensive, But There Are Ways To Tell the Truth And Reduce The Consequences

David D. Mallet

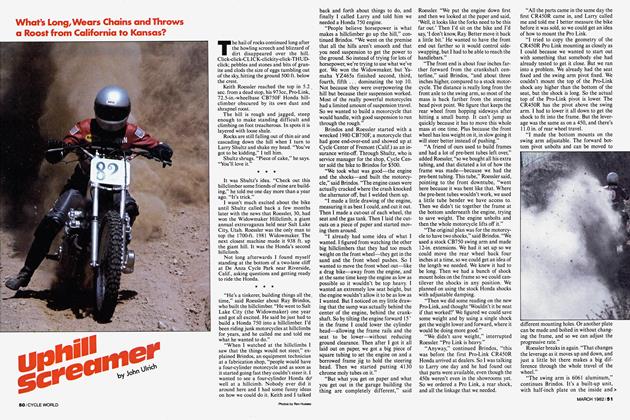

Drat. You've been blitzing along California's unofficial roadracing course (Highway 1) with such savoir faire that King Kenny may consider an early retirement. Alas, you glance into the rearview mirror and feel the sudden need for a large bottle of Rolaids. Amid the blur of the quickly-receding center line is a flashing red light.

Jiggers. It’s the cops.

As you slowly pull into the nearest turnout, you wonder why you didn’t follow your first instinct to artfully evade the man in the Smokey Bear hat. The Man might as well take it all: your wallet, all earthly possessions, spare cash, road maps, extra spark plugs, driver’s license and insurance policy. Sadly, you were caught in your jockey shorts cranked over at 55 mph around a hairpin marked at 10 mph, with sparks flying off your footpegs, stands, pipes, knees and other loose parts. Nothing to do but passively accept your fate, right?

Maybe not.

The problem with giving up and paying the fine is that this usuallysmall contribution to local government may be the most minor of your problems. Typically, a conviction will result in your having points on your driving record, and if enough points accumulate during a given period, the state department of motor vehicles may suspend or revoke your driver’s license.

The collateral consequences of the conviction don’t stop there, either. The stiffest penalty may flow from that expensive item known as insurance. Insurance carriers frown upon riders whose records show a repeated pattern of speeding or who have been convicted of more serious offenses, such as negligent or reckless driving. Also, consider other ramifications: if you think that the solution to the insurance burden is to not carry insurance, your local DMV may not permit you to drive unless you show proof of insurance. And, tickets you receive while riding a motorcycle may equally affect your automobile insurance. Even if you are rich enough to pay what can be as much as $ 1000 per year more for a poor driving record, because of the limited motorcycle insurance market (see CW, August, 1981), you may not be able to acquire motorcycle insurance at all. In short, the most recent $30 ticket could mean no more motorcycling for a lengthy period of time.

With a little knowledge, your chances of avoiding the consequences can be increased. It is the rare instance in which you should automatically pay the fine by mail or a quick plea of guilty in open court. Even in those instances in which you feel the case against you is airtight, you may be able to do a little vicarious wheeling-and-dealing to your benefit.

The idea is, that since the police have broad discretion to charge you in the first place, they also have the discretion exercised to reduce the charge to one of a lesser degree (or, ideally, to have the charge dismissed entirely).

To begin with, the police have broad discretion whether or not to cite a given offender. Obviously, many more traffic violations occur before the eyes of a police officer than that officer has the time to cite. Thus, the officer must select those individual violators of the more serious offenses. Unfortunately, this process of selection can be highly arbitrary, as the owners of sports cars or motorcycles can attest. Motorcyclists probably do receive more than their fair share of citations. To give benefit of the doubt to the well-meaning cops (a majority), the probable reason is not one of actual, overt bias on the part of the officer. Rather, motorcycles not only give the appearance of speed but are also distinctive by reason of being the exception. In other words, while we are invisible to cab drivers and little old ladies in station wagons, we are instantly noticed by the police.

The police also have broad discretion as to the nature of the charge. Take the apexstrafing example of Benny Banana and his fire-breathing 1100. The police officer who prevented Benny from continuing up Highway 1 at a delicious rate of speed might cite Benny for a basic speed violation for traveling too fast under prevailing conditions. Or, in his ignorance, the officer might charge Benny with exceeding the speed limit (55 around a corner marked 10 mph), even though the sign was merely cautionary in nature. Or, the officer might cite Benny for exhibition of speed under the guise that Benny was engaged in solo racing. If two motorcycles had been involved, the officer might charge either or both of them with a speed contest. Of, if there were a threat to life, limb or property (even to Benny himself), Officer Stoppum could charge Benny with either negligent or reckless driving. Finally, the good gendarme, if he observed Benny for several miles, might charge Benny with several distinct offenses, otherwise known as the multiple-ticket routine.

Whatever the charge you, personally, must consider the long-range economics, particularly the insurance problem. Every ticket, even a simple speeding violation for someone with a perfectly clean record, can be very serious.

The main thing you can do on your own behalf is to exercise some basic psychology with the officer at the time of the citation. The key word is: courtesy. Remember that the officer may have discretion as to the charge; excessive lip on your part is guaranteed to not only alienate the officer but also create the possibility that you will admit your own guilt. This accidental admission of guilt is one of the biggest headaches for defense attorneys. In the typical case, the violator makes what he thinks are exculpatory statements (“My pet pig, Oleander, went into labor, and I was speeding her to the hospital.”). Unfortunately for Benny Banana, the only thing Officer Stoppum heard, was: “I was speeding.”

In a nutshell, be courteous to the officer but exercise your right not to incriminate yourself. As the saying goes, tight lips and loose hips. You don’t need to offer to polish the officer’s boots, but should, instead, be commonly polite. If the officer seems particularly inquisitive about your riding style (“Man, those sparks were flying off your pegs like a 4th of July sparkler!”), it is your sworn duty to produce your driver’s license, wipe the bugs from your teeth and give your best, silent Howdy-Doody smile. Remember: the curbside isn’t the place to dispute the charges.

Depending on the charge, it may be wise to consult an attorney. Look again at the possible consequences. It may be worthwhile spending a few extra dollars for competent legal advice. Many attorneys make only a small charge, if any, for an initial consultation. If you stand to lose your license, pay higher insurance rates, are charged with a misdemeanor (e.g., negligent or reckless driving), it is essential to consult an attorney. But, even in those cases involving a small speeding ticket, you may find yourself dollars ahead by seeking professional help. The attorney may be able to help you negotiate a plea to a lesser offense, even in those situations in which the charge against you is a solid one. Plea-bargaining is a middle ground used frequently, for it helps reduce the workload of the police department.

Nonetheless, negotiation can be a positive course of action. Let’s look at a hypothetical example. Suppose Benny, who has an absolutely clean driving record, was cited at another time for speeding at the rate of 79 in a 55 zone. In a sample jurisdiction, upon conviction he would receive a fine of $ 120, have six points on his record (with suspension of license for 12 points in ' one year), plus suffer the possibility of higher insurance rates. Benny may be money ahead to pay his lawyer a small amount (for example, $75 for an hour’s work) to have Officer Stoppum reduce the ticket to one of 19 mph over the limit, as opposed to the original 24. In such a case, the fine will be reduced to $38, plus only four DMV points.

But, even before venturing to see an attorney, you should arm yourself with some basic knowledge. This is absolutely essential in those situations in which you decide to play F. Lee Bailey on your own accord by defending yourself in court.

Lest this advice to consult an attorney seem to be self-serving—I am one—remember again that the police and other officials will not ordinarily deal with lay persons. Unfortunately, many lay persons would rather do without good legal advice than consult a lawyer. Typical fears are that either the fees will be too high or the ordeal is too complicated for a mere traffic ticket.

While the method of dealing with an attorney is not the subject of this article, a few pointers will make the undertaking less costly and more effective:

1 ) Establish in advance what it will cost for an initial consultation (cheap. It shouldn’t exceed $25).

2) Find an attorney who (a) is experienced with traffic problems and (b) doesn’t think motorcyclists are out to lay physical waste to his secretary, law partner, wife, etc. The easiest way to obtain answers to these questions is to either obtain the recommendation from a friend or use the telephone book and ask the attorney himself.

3) If you want your attorney to investigate the matter, establish in advance that you are willing to authorize him to do X amount of work and that after he has ex-' pended that authorized sum of money, you (the paying client) want to have the power of decision as to whether or not to continue, and, if so, to what extent.

4) Obtain an estimate of the total charge. This is not dissimilar from obtaining an estimate from a mechanic.

5) Minimize your legal expenses by taking all court documents and a short written statement of the basic facts to your attorney.

6) Since you are paying for services, don’t be buffaloed by what you think is an incomprehensible legal system of mumbojumbo. A good attorney will explain the workings of the case to your satisfaction. If he or she doesn’t, think about finding another lawyer.

Negligent or Reckless Driving. These offenses are normally categorized as misdemeanors, rather than simple infractions. Because of this, it is very foolish to undertake your own defense. Under the typical statute, reckless driving requires that you show a “reckless disregard for persons or property.” Negligent driving, a lesser-included offense of reckless driving, requires that you “negligently endanger persons or property.” The statute in your jurisdiction may give examples of what can constitute either negligent or reckless driving: an actual collision or an instance in which the -operator of any vehicle, including the offender, undertook evasive measures to avoid a collision.

For example, if Benny Banana had scattered pedestrians during his wayward flight up Highway 1, the charge of negligent or reckless driving might be appropriate. But, where no such endangerment occurs, the charge is probably inappropriate. A real life example occurred in the author’s home town, where certain nonmotorcycling police officers undertook to charge several individuals with negligent driving for popping low-quality wheelies on public streets. The charges weren’t proper, since there was no actual endangerment to anyone. In general, look to the attendant circumstances. Was there an actual endangerment of persons or property, as qualified by the location of the offense, the number of people or types of property in the vicinity, the proximity of persons or property, speed of the motorcycle, road/ ,weather/lighting/traffic conditions and, lastly, your riding experience?

Then, if you don’t think you should have been charged, go and see a lawyer.

Speeding. This is a little devil that, in its various forms, haunts us most of all. In all instances, the police must prove that:

1 ) You were the individual operating the 'motorcycle;

2) You were voluntarily speeding;

3) The posted speed limit was XXX miles per hour;

4) The officer observed your speed to be in excess of the limit;

and

r 5) The measuring device used by the officer was accurate.

While these elements of the prima facie case may sound like tame stuff, you would be surprised at the occasional difficulty encountered by the police in proving all of the elements.

i» Many a traffic case has been lost by the police by virtue of the fact that the officer was unable to make positive identification of the operator of the vehicle at the time

the offense was committed. This lack of identification will occur most typically when there is a break in visual contact between the officer and you after the offense has been committed. This is not to suggest that you follow the Neanderthal instinct to evade the police. However, if you are lucky enough to be caught standing next to your non-running motorcycle after the officer lost sight of you for a couple of blocks, the chances of him identifying you are somewhat lessened. This is particularly true if you have had the good fortune to shed any identifying clothing. Your good fortune is compounded if you were wearing a non-descript helmet, for helmets tend to look the same, especially from the rear.

The element of “voluntariness” is not the same as “willfully.” In other words, you do not have to be speeding intentionally to be cited. You could, of course claim that your throttle hand went into immediate, uncontrollable seizure (“I saw a Suzuki GS1100, Your Honor, and my hand went into spasmodic fits”), but Hizzoner will receive this argument with the same disfavor as he would a claim that you were unduly harrassed by the officer. Better you should claim to have a weak heart, and bring a note from your mother to court.

Occasionally, you may be able to prove that you were not put on notice as to the posted speed limit, as in those situations in which you physically could not see the signs.

But, secondary perhaps to the inability of the officer to identify you as the offender, the best plan of attack is against Nos. 4 and 5 above.

Non-Radar Speeding. The officer must show that he was afforded an adequate opportunity to observe and accurately measure your speed. Without radar, the only effective manner in which this can be done is for the officer to follow you in a patrol car in which the patrol car’s speedometer has been recently and competently calibrated. For your part, the most likely defense you will have is that the officer didn’t clock you for a lengthy enough distance; that because of this insufficiency, the officer himself wasn’t able to maintain a steady rate of speed. If you can show that he accelerated after you and, because of traffic, was unable to maintain a steady speed, your chances of prevailing are good.

Radar speeding. Radar has been coming under increasing fire, and several editorials have forecast radar’s near-future demise. Unfortunately, it appears that what will happen is that radar will actually get better electronically. No more trees that can be clocked at 85 mph.

Despite the technological advances, radar can be challenged. The officer bears a heavy burden of proof to establish his testimony. He must show that he operated the machinery without human error and

that the machine was mechanically accurate. Usually, the officer will testify that he knew how to operate the machine and that it was in good working order. Most defense attorneys would make mincemeat of such insufficient proof.

Your task is to show that there is doubt in the operation. Motorcycles in particular pose special problems for radar. Bikes have substantially less frontal and side areas than do automobiles. Also, the shape and configurations of motorcycles are such that a smooth surface is not presented. Some police officers believe that the irregular configuration of a motorcycle can cause deflection of the radar waves and, hence, an erroneous reading. Contrary to popular belief, radar reflects solid surfaces, including fairing, rider, helmet, saddlebags, etc.

You may be able to show that the police officer had insufficient training. Some courts will be inclined to rule in your favor if the cop’s training took the form of the radar manufacturer’s short course, especially if the officer has not had much in the way of field experience. But, if the officer received extensive training and has had years of radar experience, don’t waste your time trying to show him up.

You may decide to ask the court to permit an on-the-scene demonstration of the radar. While the court may not want to be bothered with such an inconvenience, the author believes this to be a last-ditch, important undertaking in winning a radar case. During the course of investigating this article, the author spent time watching an experienced traffic cop use an accepted radar device. The officer demonstrated that he could clock nearby power lines at 14 mph, and the patrol car’s heater fan showed itself to be a participant in the race. The radar reading jumped 12 mph

while clocking a non-speeding car, ostensibly due to the interfering presence of a metal speed limit sign between the patrol car and clocked vehicle. In short, radar, even in the hands of an experienced police officer, can err.

Each traffic violation has its own unique set of facts, and no one article can give you the information necessary to defend and win.

However, with some basic knowledge, perhaps the help of an attorney, and the incentive to spend some time working on the problem, you may find that you do have an alternative to simply paying the fine and worrying about the consequences later.