UP FRONT

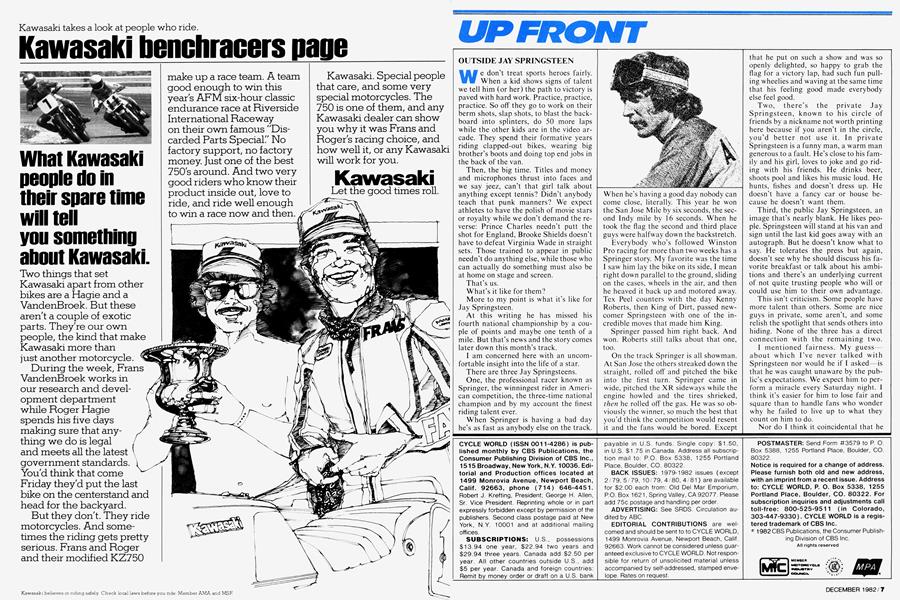

OUTSIDE JAY SPRINGSTEEN

We don’t treat sports heroes fairly. When a kid shows signs of talent we tell him (or her) the path to victory is paved with hard work. Practice, practice, practice. So off they go to work on their berm shots, slap shots, to blast the backboard into splinters, do 50 more laps while the other kids are in the video arcade. They spend their formative years riding clapped-out bikes, wearing big brother’s boots and doing top end jobs in the back of the van.

Then, the big time. Titles and money and microphones thrust into faces and we say jeez, can’t that girl talk about anything except tennis? Didn’t anybody teach that punk manners? We expect athletes to have the polish of movie stars or royalty while we don’t demand the reverse: Prince Charles needn’t putt the shot for England, Brooke Shields doesn't have to defeat Virginia Wade in straight sets. Those trained to appear in public needn’t do anything else, while those who can actually do something must also be at home on stage and screen.

That’s us.

What’s it like for them?

More to my point is what it’s like for Jay Springsteen.

At this writing he has missed his fourth national championship by a couple of points and maybe one tenth of a mile. But that’s news and the story comes later down this month’s track.

I am concerned here with an uncomfortable insight into the life of a star. There are three Jay Springsteens.

One, the professional racer known as Springer, the winningest rider in American competition, the three-time national champion and by my account the finest riding talent ever.

When Springer is having a bad day he’s as fast as anybody else on the track. When he’s having a good day nobody can come close, literally. This year he won the San Jose Mile by six seconds, the second Indy mile by 16 seconds. When he took the flag the second and third place guys were halfway down the backstretch.

Everybody who’s followed Winston Pro racing for more than two weeks has a Springer story. My favorite was the time I saw him lay the bike on its side, I mean right down parallel to the ground, sliding on the cases, wheels in the air, and then he heaved it back up and motored away. Tex Peel counters with the day Kenny Roberts, then King of Dirt, passed newcomer Springsteen with one of the incredible moves that made him King.

Springer passed him right back. And won. Roberts still talks about that one, too.

On the track Springer is all showman. At San Jose the others streaked down the straight, rolled off and pitched the bike into the first turn. Springer came in wide, pitched the XR sideways while the engine howled and the tires shrieked, then he rolled off the gas. He was so obviously the winner, so much the best that you'd think the competition would resent it and the fans would be bored. Except that he put on such a show and was so openly delighted, so happy to grab the flag for a victory lap, had such fun pulling wheelies and waving at the same time that his feeling good made everybody else feel good.

Two, there’s the private Jay Springsteen, known to his circle of friends by a nickname not worth printing here because if you aren't in the circle, you’d better not use it. In private Springsteen is a funny man, a warm man generous to a fault. He’s close to his family and his girl, loves to joke and go riding with his friends. He drinks beer, shoots pool and likes his music loud. He hunts, fishes and doesn't dress up. He doesn’t have a fancy car or house because he doesn’t want them.

Third, the public Jay Springsteen, an image that's nearly blank. He likes people. Springsteen will stand at his van and sign until the last kid goes away with an autograph. But he doesn’t know what to say. He tolerates the press but again, doesn't see why he should discuss his favorite breakfast or talk about his ambitions and there’s an underlying current of not quite trusting people who will or could use him to their own advantage.

This isn’t criticism. Some people have more talent than others. Some are nice guys in private, some aren’t, and some relish the spotlight that sends others into hiding. None of the three has a direct connection with the remaining two.

I mentioned fairness. My guess about which I’ve never talked with Springsteen nor would he if I asked is that he was caught unaware by the public’s expectations. We expect him to perform a miracle every Saturday night. I think it’s easier for him to lose fair and square than to handle fans who wonder why he failed to live up to what they count on him to do.

Nor do I think it coincidental that he won the No. I plate three times and then began getting sick at the races.

I have been thinking on this since my day with the Harley team at the first Indy mile.

Late in that race Springsteen crashed. There is more to some crashes than meets the eye. No bones were broken, no blood was spilled. All he did was catapult off the bike at 90 or so and get slammed into the ground.

This isn’t something I’ve experienced firsthand. But I’ve seen it enough so that if I rubbed the brass tank on a 1912 Scott and the Wicked Witch of Racing popped up and said I could win the San Jose Mile at a record speed of 102 mph provided Ld first take a hit like Springer took, I'd thank her for her time and get right back on the infield fence with my red Cycle World jacket and my photo pass.

With help Springer climbed into the team truck and they brought him back to the pits. Debbie, his girl, came as close as she dared and Jay told her, softly, politely but firmly, to keep clear. He let Bill Werner ease off his steel shoe and loosen his boots. Springsteen was in pain and shock. All he wanted was to be left alone.

They were in the middle of a circle, a silent crowd that assembled from Godknows-where, a sea of wide-eyed faces, standing and looking. Pushing through the mass came Vickie Werner, the tuner’s wife. She and her two daughters had been in the stands, watching their friend. “When the announcer said a rider was down Angela (age 10) said T know it’s Jay’ and she burst into tears.’’

The girls were too shy to come closer so they sent their mom. Other riders and tuners came into the circle, asked Jay if he was okay and went away. A second circle, people who felt close to the team but not that close, asked the inner circle for news and suddenly the crowd was more human.

They weren't morbid. They weren’t the thrill-seekers you see at a fire or an accident. They were concerned. They care about Jay Springsteen. He means something to them so when he crashed they came from the stands, the infield, the pits because they needed to know Springer was safe.

They kept their silent vigil because they wanted to do something while knowing there wasn’t anything they could do.

What they did, finally, was make Jay Springsteen take off his leathers and put on his jeans in the middle of a circle of strangers.

Then he stood up and with Debbie close by walked through the circle, out to the parking lot and the long drive home.®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1982 -

Cycle World

Cycle WorldRoundup

December 1982 By Lawyers -

Features

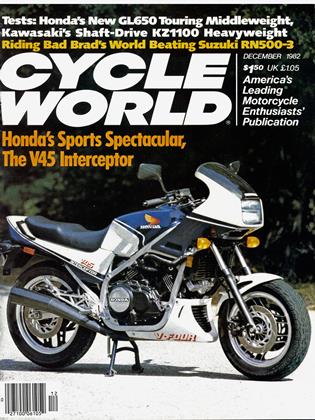

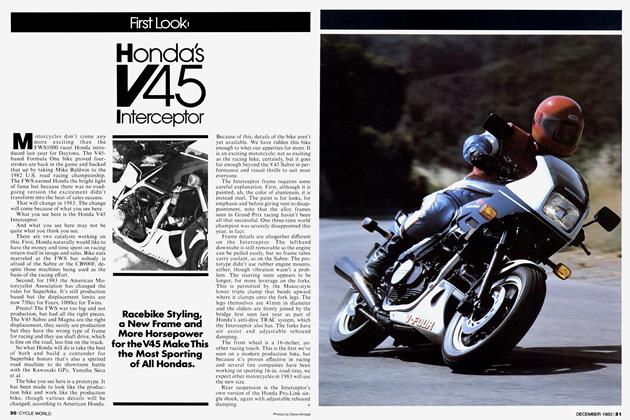

FeaturesFirst Look: Honda's V45 Interceptor

December 1982 -

Evaluations

EvaluationsHonda Silver Wing Interstate Package

December 1982 -

Features

FeaturesElevator Syndrome Part Ii

December 1982 By Steve Anderson -

Features

FeaturesHarley-Davidson For 1983

December 1982