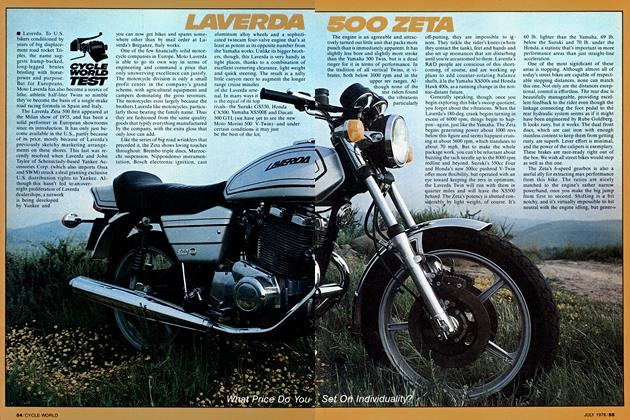

KTM 500GS AND MX FOUR-STROKE

CYCLE WORLD TEST

With Its Modified Can-Am Motor, the KTM Four-Stroke Looks -And Works— Like a One-Off Custom. A Heavy Custom.

“Why would anyone want to ride one of these big heavy four-stroke Singles when there are so many lightweight two-strokes available?” asked the guy on the other side of our garage. “Hell, a good 250 two-stroke Single will stay right with most of those big lungers and you know for sure you’ve gone mad when it’s time to start one of those beasts. Everyone who rides one of those has his own secret way of starting the damn thing. No one used to a two-stroke can get one to start,” he continued. “It must be something magical, I just plain don’t understand it.”

Of course the fellow has a point. Unless you have owned a big four-stroke Single, mastered the starting drill, felt the wonderful power impulses in your arms and butt and experienced a fulllock slide on a slippery off-camber fire road, you probably won’t understand the attraction. If you have experienced it you still may have difficulty trying to explain it to your riding buddies. You might bab-

ble on about the reliability and how you hate to carry two-stroke oil on long rides, and the gas mileage. But down deep you know these things really aren’t any better than the modern two-stroke offers. What it really boils down to is the pleasurable power impulses. And that alone is enough to keep large companies building them, and individuals building custom-framed one-offs. It also explains the rebirth of the big four-stroke Single.

Rotax, the engine company owned by Bombardier, which also owns Can-Am, started developing a new four-stroke Single three years ago. When the engine got into production the Austrian engine company sold engines to Can-Am and any other company that wanted them. Since KTM is just a few miles down the road from Rotax, KTM helped in the development of the engine’s top end and of course bought some of the engines when they became available. After a somewhat lengthy development time, KTM has two production bikes with the 500cc Rotax single engine. Both models have single shock rear suspensions and both will be available as ’83 models sometime this fall.

Both models, the GS enduro and the> motocrosser are the same bike, the GS having a center stand, enduro lights, brake light switch, larger rear fender and a rear frame loop. The motocross model, which really isn’t intended as a motocross racer, but a stripped bike for the hard-core off-road rider, doesn’t have any lights or other unnecessary parts, but does have the same Japanese electrical system with 190 watts of output. If you want to attach a couple of lOOw quartz halogen lights it’s no problem. Our GS enduro was a production bike offered in Europe as well as the U.S. The U.S. version has a different silencer, a 4 in. Trapp instead of the huge boomerang-shaped muffler on the European model. The motocross bike was the final prototype of an American-only model. The MX will come with longer travel forks, 11.7 in. compared with 10.6 in. for the GS. The Marzocchi forks have 40mm stanchion tubes on the GS, 42mm stanchions on the MX. The MX will also come with a bolt-on side stand instead of the center stand.

Excellent suspension travel and components also come stock on the rear of the bikes. Both U.S. models have American-made Fox Twin-Clicker shocks (European models use White Power shocks) connected to KTM’s Pro-Lever risingrate linkage. The Twin-Clicker Fox shock has an aluminum body, remote reservoir with a knob on top that adjusts compression damping to eight different positions, and an adjuster knob above the lower clevis that adjusts rebound damping to 30 positions. Both adjusters are easily reached and adjusted. We found the standard setting very close to our liking, but, that’s why they are adjustable. Spring preload is also adjustable but reaching the adjuster wheel at the top of the shock isn’t easy. The shop manual suggests you remove the left side cover, airbox cover, air cleaner and inlet hose. KTM reps suggest loosening the inlet hose clamp, removing the two lower subframe bolts and tilting the sub-frame forward. Yes, the sub-frame bolts on just like the two-stroke motocrossers from KTM. Anyway, the spring preload adjustment is a bitch to get at. Luckily, it too suited our riders in its stock 10.0 in. spring length position. The Pro-Lever rockers under the swing arm appear the same as those used on the ’82 two-stroke KTM motocrossers but KTM spokesmen say there is a slight difference in the lengths of the rocker and struts.

KTM’s single shock system is similar to the designs used by other factories, but has important differences. KTM uses a straight rocker that attaches to the frame at the front, to the lower shock shaft at the rear, and to the swing arm via short aluminum struts just in front of the lower shock mount. The top of the Fox shock mounts to the chrome-moly frame’s backbone end, very much like Honda’s Pro-Link does. At first glance the frame and aluminum swing arm appear transplants from the 1982 production KTM two-stroke motocrossers. The swing arm is the same, the frame is heavier and stronger to handle the heavy power impulses produced by the big four-stroke Single. Once the tank and seat are removed, an extremely beefy frame with a huge main backbone and front downtube is exposed. And massive boxed gusseting is placed between the two. These frame parts look too big for the bike but make sense when you learn the frame members are the oil tank for the dry-sump engine. The filler hole is located just ahead of the fuel tank, just aft of the steering head. The plug has a dip stick connected to it, marked with a high and low mark, and fitted with double O-rings so oil and fumes don’t escape. The huge front downtube terminates at about the base of the cylinder. Two smaller tubes start at this point, forming a wishbone. They roll under the engine then turn and circle the back side of it before connecting to the end of the backbone tube. The downtube end is fitted with a four-bolt plate. The plate can be removed to change or clean the oil filter, one of three on the bike. The other two are part of the engine. Like the production two-stroke motocrosser, the fourstroke frame has a bolt-on rear section. The GS enduro rear section has a frame loop to help support the big rear fender and taillight, the MX doesn't. The bolton rear makes shock adjustment and maintenance easier and if you crash really hard and bend the rear tubes beyond repair, the whole section can be replaced for approximately $75.

The Rotax 504cc four-stroke engine is a modern design right down to its looks: Some people like the styling, some think it looks like a fire hydrant. It has a fourvalve head, overhead cam driven by a cog-belt, a five-speed transmission and dual exhaust ports. Many components are identical to the parts used in CanAm’s 500 four-stroke, some are different. The biggest difference between the two is the stroke. The Can-Am Rotax engine has an 89.0 x 79.4mm bore and stroke configuration that totals 494cc. The KTR Rotax engine has an 89.0 x 81mm bore and stroke for a total of 504cc. Can-Am’s engine uses 30mm intake and exhaust valves. The KTM Rotax has 30mm exhaust valves and 34mm intake valves. The Can-Am has a Mikuni carb, the KTM a Bing, both are 36mm. Add a more radical cam and higher compression for the KTM and you have the difference between the two engines. Innovative engineering appears in the Rotax engine: the rocker arms are connected in pairs but operated by a single arm complete with a roller instead of a flat shoe, the cam turns in roller bearings, the top of the rod uses a bronze bushing, the bottom a needle bearing, the crank rotates on caged ball bearings, the three-ring piston has a chrome top ring, the transmission is lubricated by an oil spray, the clutch basket turns on caged needle bearings, the clutch has eight plates, and the ignition is a pointless Japanese-made ND.

Oil from the frame leaves the bottom of the front downtube after passing through an in-frame filter, enters the engine and goes directly to one side of the double oil pump, is pumped through a one-way check valve then through a replaceable engine oil filter. After leaving the engine filter the oil is pumped into a T-junction that directs part of it to the right side main bearing and an oil slinger that throws oil on the bottom of the piston and over the transmission gears, the other half goes to the head to lubricate the rocker arms and cam. Next, the oil from the head drops into the left side cover to lubricate the left main bearing, clutch and bearings. As it falls to the bottom of the pan it passes through a fine wire screen, the third filter. The engine uses the dry-sump principle, meaning no oil is stored in the engine’s lower end. All the oil reserve is in the frame and the oil pump capacity is greater than the volume reaching the lower end. The cogbelt is one place the oil isn’t pumped. The belt is in a chamber on the left side of the engine and care is taken to keep all lubricants out. Cog-belts are designed to run dry. The inspection cover is easily removed by taking out a few alien screws. Once inside the belt looks too loose when properly adjusted. It runs rather loose intentionally. An eccentric tensioner outbound of the belt and another roller on the inside of the belt stops whip. KTM’s owner’s manual recommends adjusting the belt every 900 mi. and replacing it every 9000 mi.

Wheel assemblies are as impressive as the rest of the big KTM’s parts. The rear hub and brake are the same as used on the 495 motocrosser. The aluminum rim is different. The motocrosser has Sun rims, the four-stroke uses Nordisk deepcenter aluminum rims. Spokes are pencil-sized jobs that look strong enough for a 1000 lb. bike. The brake backing plate is a full-floating design on the MX model, a short static arm attaches to the swing arm on the GS. The front hub is a spool-type with a 230mm disc rotor. A Nordisk rim is also used and laced with spokes nearly as large as those on the rear. The disc caliper and handlebarmounted master cylinder are made by Brembo. The line between the master and slave cylinder is nicely shielded and routed and the hand lever is a dogleg type. Tires are Metzelers.

Many small parts go into building a complete motorcycle. The quality of these parts and pieces are first rate on the KTM four-strokes: A 520 chain is nicely routed through an aluminum chain guide just in front of the rear sprocket and it’s kept away from the airbox and frame by another guide on the top front of the swing arm. The rear brake pedal has a heavily serrated top, the shift lever has a folding tip, the throttle and left hand lever are made by Magura, the chrome-moly steel bars are the right shape and height, the grips are good, the air cleaner is a K&N, the right side of the airbox doubles as a tool box and a good set of hand tools comes with each bike. And all of the plastic parts are nicely made and durable. Complaints? The seat is the same narrow and hard item used on the two-stroke motocrossers and it shouldn’t be. A wider and softer seat would better suit the bike’s personality and make long off-road rides easier on the rider’s bottom. When that sorebottomed rider gets off the KTM GS, he has another problem in store. Getting the bike on the centerstand is hard work. There is no catch or footing on the stand, so the rider carefully picks it from beside the swing arm, holds it down with his toe, hunts for a convenient grab spot to lift the bike, and then burns his hand on the exhaust while he desperately fumbles the bike onto the stand. It’s awful.

Starting an open four-stroke Single can be an extremely frustrating chore for anyone who hasn’t owned one. All modern four-stroke Singles have some type of compression release device to ease starting. The idea is to hold a valve open, reducing compression pressure so the starter can turn all of the various parts fast enough for the ignition to fire. Some bikes have completely automatic units connected to the kick starter’s mechanism, others like the KTM have a manual compression lever on the bars. The procedure on the KTM is to bring the piston to a compression stroke, pull the compression release lever so it becomes easier to push the kick lever, carefully push the kick lever moving the piston past top dead center and the maximum compression point until a yellow spot shows in the sight window at the top left of the cam drive cover. Then let the kick lever return to the top of its stroke, make sure the choke is on if the engine is cold, and kick the lever as if mad at someone. If you kicked hard enough and don't turn the throttle, the bike will start right up. If you turn the throttle or give a halfhearted kick, nothing will happen, not even a burp. Try again. If the engine still doesn’t start, pull the compression lever and turn the engine over rapidly three or four times and then repeat the starting drill. After the engine starts, let it idle for a few minutes until the engine warms. If the throttle is turned too soon after starting the engine will probably die. It has to be warm before it’ll take any throttle. If you aren’t used to starting big Singles, you may swear it can’t be done. With practice it can as long as the starter does it by the book if you just kick at it, not bothering with the sight window, you’ll be very lucky to get the bike running. It'll only start using the proper procedure! Some of our lighter staff members had great difficulty starting the 500 thumper. Very frustrating for them. Others, the heavier ones and those who have owned big-bore singles before, could start the bikes almost every time with a single kick, hot or cold.

That done, the rider is instantly aware of almost no internal engine noise; no valve clatter, no cam drive noise, no thrashing or clanging. The GS with counterbalancer runs smoothly with little or no power impulses to shake the frame and front wheel while idling. The MX, still in prototype form, shakes and the front wheel jiggles around while idling. It too will be equipped with the counterbalancer in production form.

Clutch pull is a little harder than we’d like but still nothing like an open Maico. The transmission shifts into low gear with no lurching or clanging. Getting the bike moving is no problem although the clutch does engage suddenly and the tendency to leap from a dead stop is more severe than a two-stroke, but no more so than other four-stroke Singles. Low gear is extremely low, 24.03:1 and the jump from low to second is wide, (16.52 for second). The rest of the gear changes are spaced about right but using a bigger front sprocket or smaller rear would make for a better gear spread. For riding in mountain terrain, the stock gearing is fine, for open country the bikes would be better with taller secondary gearing.

These bikes are big and they are heavy. Having the oil in the frame’s backbone and the tall engine puts much of the weight at the top of the bike. Slower speeds amplify the top heavy feel and the bikes are somewhat clumsy despite the steep head angle of 27°. As speed increases, so does stability and the bikes feel less top heavy although the feel never completely disappears. Horsepower is adequate but nothing spectacular. May-

be a little more power than an XR500 but not much more. Forget about wheeling with horsepower, only someone really used to riding large four-stroke Singles will be able to get the front wheel in the air, and only between first and second at best. The trick is to short shift, using the torque. Blipping the throttle to elevate the front wheel to clear ditches and such is out of the question. The lack of power and the heavy engine with much of its weight on the front wheel eliminates the possibility. Just charging into them is the

only way. Luckily the great suspension at both ends allows it, as long as some restraint is exercised. Any off-road bike weighing 300 lb. or more (296 and 310 with a half tank of gas) has limitations. Trying to race an open motocrosser of the modern two-stroke design across deep whoops or through an area with sharp washouts isn’t a smart thing to do. Plan on having a sore or injured body if you try. The sheer weight of the bike may suddenly turn you off course 30° or 40°. When it happens it happens sudden> ly and with no warning. It happened several times during the three days we rode the bikes. Up to that point, the bikes get through the bumps and rough stuff better than any heavy bike we’ve tested. These bikes aren’t intended as pure race bikes, they are serious play bikes. Evaluated as such, they are better than any four-stroke play bike you can buy. The weight of the MX is about the same as an XR500R for example. The difference is the quality and travel of the suspension, the strong, flex-free frame and swing arm and the strong brakes.

Most 300 lb. dirt bikes get difficult to stop above 50 or 60 mph. Not the KTMs. If anything the front brake may be a little too much for some riders. It is extremely strong and a little sudden. Our faster riders loved the disc, our slower riders were a little spooked although none of them crashed due to it. The rear brake is large and everyone thought it was just right. But, back to the suspension. The forks are some of the plushest we’ve tried. The 42mm jobs on the MX are slightly better and have a little more travel but the 40mm GS forks work almost as well. Both soak up small ripple type terrain with ease and don’t bottom on deep ditches and such. The rear shock can be easily changed to do whatever you think it should.The rebound and compression damping are easy and the adjustments actually make a difference. Spring preload isn’t as quick to change but once set shouldn’t require further attention. Both bikes had the fork oil level set at 7.5 in. when compressed. We thought the setting correct on the GS but the MX dove quite a bit under hard braking. We raised the oil level to 6.5 in. from the top of the tubes and eliminated the complaint. Then the fork action suited all our different weight riders. The rear rebound damping was left at the stock settings but we reduced the compression damping a notch or two depending on the weight of the rider. Only our lightest riders needed the spring preload backed off.

Anyone used to riding two-stroke Singles will have a day or so of adjustment before they are comfortable on the big four-strokes. Timing is one of the biggest stumbling blocks. A quick blip on the throttle is all that’s needed to raise the front wheel over rolling terrain on most two-strokes. The same blip on a fourstroke will result in a front wheel landing. It’s necessary to turn the throttle on sooner and more when riding four-stroke Singles. Same thing applies when sliding corners. Turn the throttle on sooner and farther. Big, long, full-lock slides are possible on the KTMs once your timing adjusts. The bikes handle much like a good motocrosser when entering corners—they stay straight. When the rider adjusts and dives into the corner deep, (the compression will help slow you down) turns the throttle on early, and pitches the bike flat track style, the KTM responds with beautiful half-mile type slides. No sawing, no wallowing or attempts at high-siding. The Metzeler tires add to the secure feel, as does the front end which never pushes or lets go suddenly.

KTM 500GS & MX FOUR-STROKE

$3095 ($3080)

Trying to make square turns simply doesn’t work on the KTMs. Too much weight and not enough brute power. KTM or Trapp is going to offer a 3 in. high performance silencer as an option to use in place of the standard 4 in. unit. We had one of the 3 in. prototypes along and installed it on the MX the third day. It increased the power dramatically. It had 18 defuser discs which added slightly to the noise level but not enough to be concerned about. With the accessory 3 in. Trapp it was possible to make tighter turns and square turns. Without it, only wide turns could be made. The increase in power made the bike much easier to place where you wanted it. Lofting the front wheel was easier also. The 3 in. Trapp is still a legal spark arrester and a worthwhile addition if more power is wanted. Price wasn’t set yet but it should go for less than $40.

Since we planned on riding long distances without gas (the mountains and desert around Prescott, Arizona) we got a 3.3 gal tank for the MX model (it comes with a 2.4 gal. motocross tank, the GS has a 3.3 gal. tank stock). It’s another available accessory and slips right on. Gas mileage, one of the claimed advantages of four-stroke Singles, isn’t all that wonderful. Hard riding by desert experts and B enduro riders averaged 20 mpg. In other words, 60 to 70 mi. per tank. Riding the bikes at an easier pace increased the range to around 100 mi.

These bikes are more suited for open riding like Baja than tight woods. Riding in the woods, even open woods, is work. Sixty or seventy miles of woods riding is a chore. You’ll feel like you’ve been doing push ups with someone on your back. And really tight stuff where you have to try and jump logs is torture. Same thing if you get into a rocky box canyon where you have to physically lift the bike to turn it around—better be in excellent shape. Stay in the open area and on the slider fire-roads, that’s where the big Single is FUN.

Even with these limitations, the same ones that apply to other heavy off-road bikes, the KTMs comes out way ahead of the competition. There’s not one cheap or questionable part on these bikes. The suspension at both ends is super and has enough travel, the frame and swing arm won’t need replacement, ditto the smaller components. Thirty-one hundred dollars sounds like a lot of money for one until you check into building a custom framed four-stroke and learn it’s going to run between five and seven thousand dollars, then you start to see what a bargain the price is. If you want a four-stroke Single with all the right parts already on it, check out one of the 1983 KTMs. You won’t need to take out a second mortgage on your house to buy an accessory frame and suspension components. ESI

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1982 -

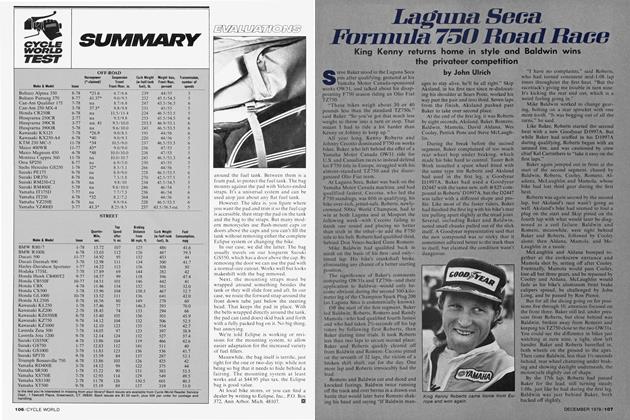

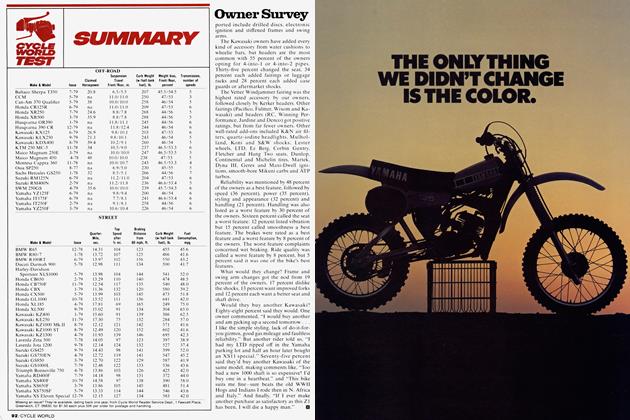

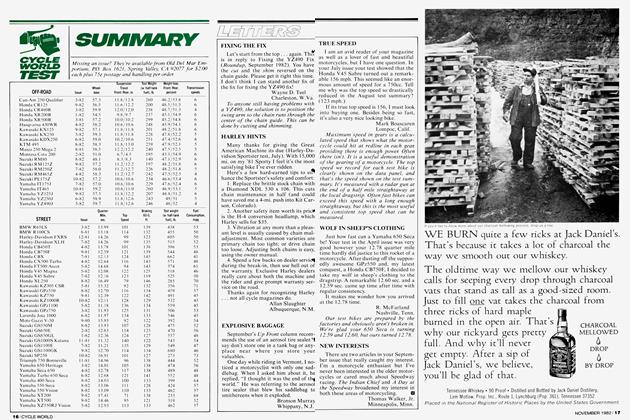

Cycle World Test

Cycle World TestSummary

November 1982 -

Cycle World Roundup

Cycle World RoundupAutomatically Faster

November 1982 -

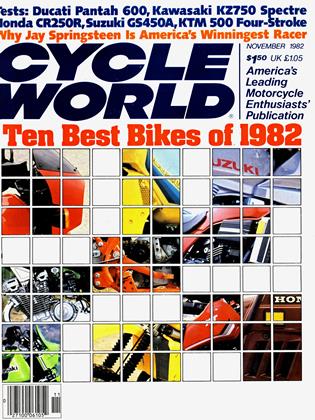

Ten Best Bikes of 1982

Ten Best Bikes of 1982Even When They're All Good, Some Are Better.

November 1982 -

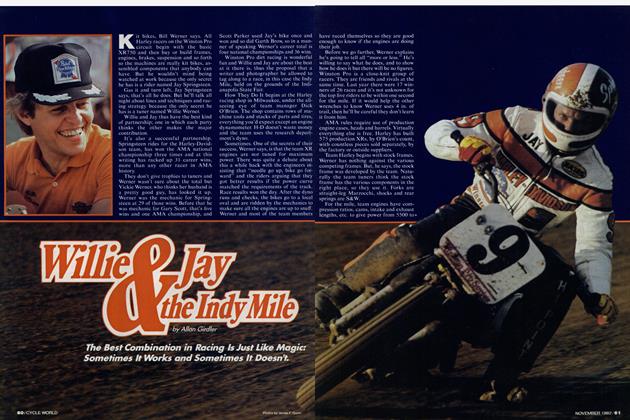

Competition

CompetitionWillie & Jay the Indy Mile

November 1982 By Allan Girdler