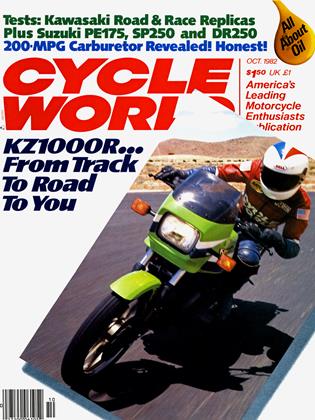

THE 200 MPG CLUB

You Remember Us. We're the Folks Who Didn't Go 200mph at Bonneville. Now We Haven't Gotten 200 mpg.

Steve Kimball

Yes, friends, there is a 200 mpg carburetor. I’ve seen it, and watched the motorcycle equipped with it. Honest people have carefully measured hundredths of a gallon of gasoline filling the gas tank on the 200 mpg motorcycle after it had ridden up the coast of California at normal highway speeds. You don’t have to buy a $9.95 book advertised in Mechanix Illustrated to find the 200 mpg carb. It’s not a secret, the patent isn’t owned by an oil company and there isn’t one mounted on a 1936 Buick hidden in a warehouse in Flint, Michigan.

This 200 mpg carburetor belongs to Charlie Perethian. The how and why of his carburetor requires some explanation. . .

Until the last year or so there were no trophies for motorcyclists who could get

the best mileage, no win posters from the manufacturers of high mileage bikes. No world championship for mileage exists. You don’t get your picture on the evening news by winning a mileage contest. Hunter S. Thompson doesn’t write books about riding on an economy run. Neither does P. J. O’Rourke.

There is someone out there who would like to change that, however, and he may have enough notoriety to do it. He is Craig Vetter, leader of a revolution in motorcycle fairing design and now a prosperous former fairing manufacturer and genuinely interesting fellow.

Craig is infatuated with motion. He has a giant metal building filled with all sorts of old motorcycles and a few strange cars, not things usually seen in museums, but just old machines that he likes and wanted to own. He’s tried racing motorcycles and flying ultra-light airplanes and as a result of those experiences has even developed his own idea of a wheelchair, lighter and easier to operate than the conventional collection of steel tubes. His is an inventive mind.

Vetter is also a natural media person. He has an appreciation of media attention matched only by a few politicians and entertainment types, so to showcase fuel efficiency, Craig has created an economy run. As he has done with everything else in his life, his economy run is not like any others. He has tried to keep it realistic, by running it on fairly normal roads and setting time limits that require realistic riding or driving.

Last year he put on the inaugural Vetter mileage contest, held in the rural central California county of San Luis Obispo. That being my favorite part of the world and adopted home town, I used it as an excuse to ride a tiny Honda C70 up the coast and somehow won the perpetual industry trophy, thanks mostly to the good work Mr. Honda did 25 years ago when he originally designed that bike.

This year the run would be different, starting at San Luis Obispo and running up the Coast Highway to Monterey the same weekend as Laguna Seca, always an exciting race and a lovely racetrack. The route would be longer than last year’s, and the average speed would be much higher. Though Highway One up the California coast has a well deserved reputation as a scenic winding road, it’s much straighter than the HO-scale lanes of the previous route, which affects economy and choice of motorcycle.

The only way the Passport kept up with the average speed last year was by flogging through the corners. No way the 70cc Passport would run the 55 mph needed on the long relatively straight sections of the coast highway. That calls for something bigger. Our normal mileage tests have shown that bikes under about 500cc often get better mileage around town than they do at steady highway speeds. Bigger bikes get better mileage on the road, cruising 55 or 60 or more. What this economy run called for is a careful mixture of both sizes, a small engine with high gearing and maybe a little detuning.

Because the Cycle World mileage loop includes about one half highway travel, really tiny machines haven’t gotten notably better mileage than bikes around 250cc. Perhaps the most noteworthy performance has come from the Yamaha Exciter I 250 because it is tuned for lower engine speed than some of the other 250cc bikes. But if speeds are held down, a bike could be geared up and if the rider is willing to crouch down and pretend he’s a gas cap, an even smaller engine might help. To be strictly freeway legal, the SRI85, also known as the Exciter 185, was picked.

Like the larger Exciter, the 185 is a good running bike with better than average power at low and medium engine speeds. It also has only a four-speed gearbox with wide ratios. Its electric start and good clutch would make coasting a little more convenient and with only the four speeds it would be easier to shift to neutral.

Figuring that the most telling conditions for the motorcycle would be highway travel, I laid out an all highway loop. Run at normal freeway speeds with everything set to specifications, the 185 returned 90 mpg, an outstanding figure. This is not only better than any other bike has done on the test, but significant improvement seemed possible.

Encouraged by a good baseline figure, the next step was to make changes that cost nothing. The biggest improvement of all would be to change the rider position to reduce frontal area. The stock 185 handlebars force the rider to sit straight up. It’s not a bad posture for typing out stories about motorcycles, but it catches a lot of wind on the road. Just crouching down on the bike would add at least 5 mph to the top speed, or it would save gas when held at a slower speed. To help get out of the wind the simplest change was to swap the handlebar position. After pulling the grips and controls the handlebars came off and were reversed, extending down below the steering head. It was also possible to cut a couple of inches off each end of the handlebar, making everything fit just a little better. As strange as this sounds, the handlebars fit surprisingly well. I could now lean down on the gas tank or on the small pad mounted on the tank and find a comfortable position. While the bike was in the garage the tires were pumped up to 50 psi, the carburetor was pulled off so the float level could be dropped 2mm and the needle lowered slightly by removing a small washer, and the valves adjusted to maximum clearances for reduced effective duration.

None of these changes hurt the small Yamaha’s running noticeably. The lower bars took a couple of miles to get used to. The engine still ran well, with no signs of excessive leanness. Ridden on the same loop maybe a little more gently the 185 now needed 0.90 gal. of gas to run a 100 mi. loops for 111 mpg, fantastic mileage for a relatively stock motorcycle that hadn’t had a penny spent to improve mileage.

Astounding numbers can be a little misleading, though. Taking advantage of what could be done with the stock bike added nearly one-quarter to the mileage. That would be the same kind of gain it would take to improve a truck’s mileage, for instance, from 9 mpg to 12 mpg. But in terms of gas saved and dollars saved, things get much different. If the Yamaha driver rode 10,000 mi. in a year and increased his mileage from 90 to 120 mpg, he could save as much dollars and as much gas as he could if he drove his 9 mpg truck a little more gently and got 9.2 mpg over the same 10,000 mi. Either way it works out to just about 28 gal.

To make the really high mileage seem useful, other ways of thinking about it are needed. Like how useful it would be to have a 200 mpg transportation machine the next time the Arabs hold their fuel hostage and gas gets hard to get. Let’s see. If I filled all my cars and bikes I would have 56 gal. of gas available. That would> go 840 mi. in my pickup, or 1400 mi. in the small car, or 2800 mi. in the big motorcycle. But in a successful economy special it would provide 11,200 mi., enough travel to get me to work and back for two years. On 56 gal. of gas.

With this kind of crazed rationalization going on, the 200 mpg figure began getting more appealing. Vetter sent a note announcing this year’s economy run and declared that I’d better be there to defend the title. He said 200 mpg was the goal this year. The other guys were getting serious this year, too. Don Vesco was building a streamliner for Suzuki, using a 125cc motor. Paul Van Valkenburgh was talking about adapting a one horsepower four-stroke motor to one of his super-efficient human powered vehicles. Defend my title? Of course I would defend my title.

As in all performance modifications, one thing affects another. As all those people who have written us asking for jetting information know, you can’t just put on the K&N air filter and take home the trophy. Same thing applies here. I couldn’t just reverse the sprockets and make sure the choke was turned off. According to my old high school auto shop book the best economy comes at a nearly wide open throttle and the lowest possible engine speed. For driving that means get in the highest possible gear as soon as possible and then don’t go too fast. The little Yamaha had more power than I needed, so if it could be geared for lower engine speed and tuned -for that speed, it would work better.

Checking at the friendly, neighborhood Yamaha dealer turned up a 17-tooth front sprocket that would fit the 428 chain and the engine cases. That’s a sizeable change. For a rear sprocket, not only did the dealer not have any smaller replacement sprockets, he didn’t have any stock sprockets. Custom-made sprockets were available, however, if the stock rear sprocket was sent to the sprocket company. So off came the stock sprocket and it was sent to Circle Industries, with a request for a 35 and a 40 tooth sprocket.

The engine was taken to Web-Cam for an economy camshaft. Most of the work done at Web-Cam is for more performance, and they have gotten good results on a wide variety of motorcycles and cars. But Henry Pilcher and his crew were familiar with the Vetter Economy Run and were interested in the effort so they set to work measuring and calculating and grinding a new cam. Measuring the stock cam at 0.040 in. of lift, it had 215° of intake duration and 231 ° of exhaust, with 0.318 in. of lift on intake and 0.322 of lift on exhaust. This timing produced a wide powerband in the 185, extending the useful range of engine speeds from just above idle to 9000 rpm, with no surge in power anywhere. Just the sort of power characteristics needed for an economy machine in normal use, in other words. To take advantage of the higher gearing, Web-Cam produced a cam with shorter duration and higher lift, the kind of changes that would lower the torque peak from the stock 6500 rpm to maybe 6000 rpm. Not big changes, these, but enough to help boost the mileage a little. What the Yamaha ended up with was duration of 210 ° intake, 217° exhaust, and 0.354 in. of lift on both.

One way cam timing can be easily changed is by altering valve lash. Reduce the valve lash and the effective duration and lift is increased. In order to allow more tuning with valve lash, the Web-Cam grind used a very shallow ramp early on in the rotation, then sped up to a high acceleration.

With the new cam installed and the engine back in the bike, the project was temporarily halted. Two weeks after the stock rear sprocket was sent away as a pattern, nothing had come back. To get testing under way again, I checked all the Yamaha dealers in the county. None of them had a stock rear sprocket. The parts ordering computer was having difficulty at Yamaha, one dealer told me, so it would be next week if they ordered one.

Fortunately, I was not alone in the quest for more mileage. A variety of motorcycle companies, accessory companies and motorcycle enthusiasts were working on mileage specials. One of the teams, the gang from Rifle Fairings, was also working on a Yamaha 185 and, this being a casual and fun event, we had been sharing information on engine changes. A quick phone call to San Luis Obispo and the Rifle shop and one of their spare sprockets, a 38tooth alloy sprocket from C.T. Sprockets, was delivered to the local bus station half a day later.

Tall gearing, super cam and all, the Yamaha ran through the mileage loop at about 120 mpg several times. That was an 8 percent increase, but to be sure whether it was gearing or cam, in went the stock cam again. Mileage dropped back to the 110 mpg level. The cam did provide more power at the lower engine speeds and it was easy to run the bike with the much larger frönt sprocket and tiny rear sprocket.

Experimenting with carb jetting was my first venture in the real world of high performance tuning. The real world of high performance tuning (RWHPT) differs from everything ever written about the subject because Things Don’t Work. Take for example what happened when I lowered the needle in the carburetor. The bike ran fine, mileage dropped 10 mpg and the plug looked as though the bike were running richer. Substitute a smaller main jet and the same thing happened. Return the carb to stock and mileage bounced back up to around 120 mpg.

By this time Charlie Perethian from Rifle Fairings would call about once a week and we’d swap results. Actually, he had results, I didn’t. His experience with jetting was the same as mine. He even tried letting the local Yamaha dealer change the jetting with the help of the Yamaha exhaust gas analyzer. It didn’t help. Finally, he tried another carb, still the stock 24mm TK for a 185 Yamaha, but just changing one stock carb for another helped his mileage. Mine went back to nearly stock, only a 2mm lower float level remaining mostly because Something Had To Be Done.

Ignition timing has always made a big difference in fuel economy and that’s one technique that had always worked for me. Advance the timing until the engine pings, then retard it slightly and mileage picks up along with power. I’ve done that with every car or motorcycle I’ve ever owned, all to good effect. Except the Yamaha had fixed timing. Pickups for the electronic ignition were mounted solidly in the cases. Perethian worked around this by remounting the magnets in the flywheel for about 4° of advance and got good results. He also damaged the flywheel enough to eliminate the generator so he had to run total loss ignition.

Perethian had discovered some other techniques. His piston was coated to insulate it from combustion heat, keeping more heat from leaving the combustion chamber. That was good for a little more mileage. So was milling the head 0.040 in. for higher compression. I tried loosening up valve lash, going from 0.003 and 0.004 in. to 0.008 and 0.009 in. Mileage stayed the same. Opening the lash until the valves clattered doubled that lash figure, again not affecting the mileage.

Higher gearing had not yielded much improvement in mileage, though that is what had helped Perethian the most. In order to take advantage of any gearing, some kind of streamlining would be needed. Perethian was working on a shell for his bike, and he had lowered the machine slightly to lower his side area, making it less affected by sidewinds. Suzuki was having a streamlined bike built by Don Vesco, world’s fastest motorcyclist, and Honda was reputed to be working on a streamliner as they had the previous year.

To compete with these people, the world’s biggest manufacturer of motorcycles, the world’s fastest motorcyclist, and some talented plastic manufacturing people, I stopped by the local hardware store after work and bought a roll of thin sheet aluminum and a wad of strap steel to fashion brackets. I wasn’t going to give up my trophy without a fight.

According to all I had read or heard, more drag on a motorcycle came from the back of the machine than the front, so that’s where I started. All the paraphernalia on the back of the Yamaha was removed. The giant pillion seat, its support frame, the signal lights and numerous brackets holding them and even the fender and its incorporated taillight were all taken off.

Working with sheets of cardboard purloined from our art department I fashioned a wrap-around streamlined shape for the back of the bike. Aluminum sheet was cut to follow the cardboard pattern and the steel strap was bent to the same shape for support and bolted to the rear frame. The aluminum was pop-riveted to the support. With the sheet metal smoothly wrapped around the back of the bike, a tiny taillight was mounted with the turn signals tucked in tightly, just behind the seat, out of any possible draft.

Lots of irregular shapes were now smoothly enclosed, while nothing was made wider. The tailsection looked clean and neat. It added only a couple of pounds to the stripped bike, certainly less weight than the stock fender or lights. With the tailsection firmly mounted and still allowing the rear suspension to move, I headed around the test loop expecting the best mileage yet. Back in the garage, filling the tank with the same glass measuring device, the mileage turned out to be about 98 mpg. Horror. Shock. Disbelief. On with a smaller front sprocket again to check with the more normal gearing. The results were virtually the same.

Taking a fresh look at the tail in the morning the problem was apparent. Air from beneath the bike was scooped right into the inside of the tail from around the

rear tire. The lower section of the bike had less bulk than I did, and fairing the sheet metal around this area did little to reduce any turbulence on the outside of the skin, while erecting a wall for air that normally filtered up toward the back of the bike. Streamlining, it turns out, is easy to do wrong, as are many other skills.

Disappointed but not discouraged, I removed the tailsection. Without fully streamlining the machine, there were still some possible improvements to be coaxed from my roll of aluminum. All the economy record machines I’d read about insulated the engine and heated the intake mixture, though for the kinds of competition usually entered, the bike could be coasted considerably and the insulation kept the engine from cooling off too much. Still, the standard Yamaha had enough engine cooling to keep the cylinder happy when the throttle was held wide open and all of the 1 5 or so horsepower was being pumped out. With the rider in a good crouch, it shouldn’t require more than half the maximum power to run the 60 mph that would be needed for this run. So I had cooling to spare and the run would no doubt be on a cool and foggy morning up the coast. To keep things warm for the engine and also heat the intake, I fash-

ioned a sheet of aluminum that wrapped around the engine and ran from right leg to left leg. It was a simple piece, trimmed thinner than the standard width of the aluminum, and riveted to a pair of steel straps bent around from the front engine mount.

On the next mileage check the engine didn’t show any signs of running hot. It didn’t make funny smells or sounds, still idled at stoplights, and didn’t even feel particularly warm. Without as much air blowing on my pant legs, it felt as though the bike ran easier. Back at the garage I knew it was going to be a good run as I poured the first quart of gas into the tank. But then it took more gas and more and when it was all filled, the mileage was back down around 100.

A look at the plug explained the low mileage. It was brown, about the color of coffee, but without any cream added. Hot air is less dense than cold air, and just as pulling the carb heat on an airplane richens the mixture, so too did shrouding the engine. Only my mixture control on the Yamaha was never effective. Smaller number Keihin jets (there were no TK jets available at the local Yamaha shop) never made much difference, so the front shield came off and got stacked neatly on the back fairing that didn’t work. >

By the time my experiments in aluminum were finished, my hopes of keeping the trophy were piled with the bent aluminum. Reports from the Vesco grapevine indicated he was getting around 200 mpg. Actually it was Matt Guzzetta who was building the Suzuki streamliner. Matt has been such an integral and important part of Vesco’s operations for so long, it is sometimes hard to think of Vesco’s shop as other than Matt.

It was now a week until the economy run and there wasn’t any time left for extreme experiments. The Yamaha had always been an after hours and weekend project and there were no more weekends and few after hours, so the project Yamaha became a Gesture. Once again I would ride the bike to the economy run, and ride it home. There would be no trucks or chase vehicles, and somehow I was determined to carry that huge trophy back to San Luis Obispo, 240 mi. away, on the Yamaha.

Practicality is easier to accomplish than economy. Where the tiny taillight and signal lights had been mounted, I put a Vetter Roostertail storage box. It fit right behind the seat and, if anything, smoothed the closing path of the air. It also provided enough room for my cameras and film and part of the trophy, along with half a week’s worth of socks and shorts, provided I sat on the top of the box when latching it. A giant Harro tankbag carried most of the trophy, but only after it had been dismembered.

With the two-foot-tall tankbag in front and the tiny tail behind, the 185 was ready to hit the road. Leaving at 5:30 a.m. to beat some of the rush-to-work crowd on the freeways, the Yamaha settled down to an easy 60 mph. With the gearing as I had been running it (the Circle sprockets never did arrive) the Yamaha ran at 60 mph with the engine spinning somewhere around 5000 rpm. It would also pull 60 in 3rd gear, or in 2nd. In 4th it was marvelously relaxed, one of the smoothest bikes I’ve ridden.

Last year Peter Egan and I took the scenic route to San Luis Obispo, not just because there is lots of scenic between here and there, but because the tiny bikes we were riding weren’t freeway legal and we were stuck traversing the Los Angeles basin one block at a time, racing from stoplight to stoplight. The trip took nine hours on the Honda C70 and the MB5, both the machines running about 50 mph on the rare straight and level. The Passport C70, the more economical of the two, averaged 102 mpg for the trip.

Getting to San Luis Obispo in four hours this year, the Yamaha got the same mileage for the trip that the Honda 70 had the previous year. It got the same mileage over a shorter distance because it could run on freeways, so the total fuel consumed was about two-thirds as much as the smaller motorcycle had used the year before. Consider that a moral victory.

Once in SLO, I stopped at a friend’s hangar to reassemble the trophy. It would be bad form to return it in pieces. The hangar is located at the airport at the bottom of the hill from Vetter’s retreat, so all I had to do was prop the trophy up on the tankbag, strap it down with bungee cords and balance the thing while riding up the mountain. No problem.

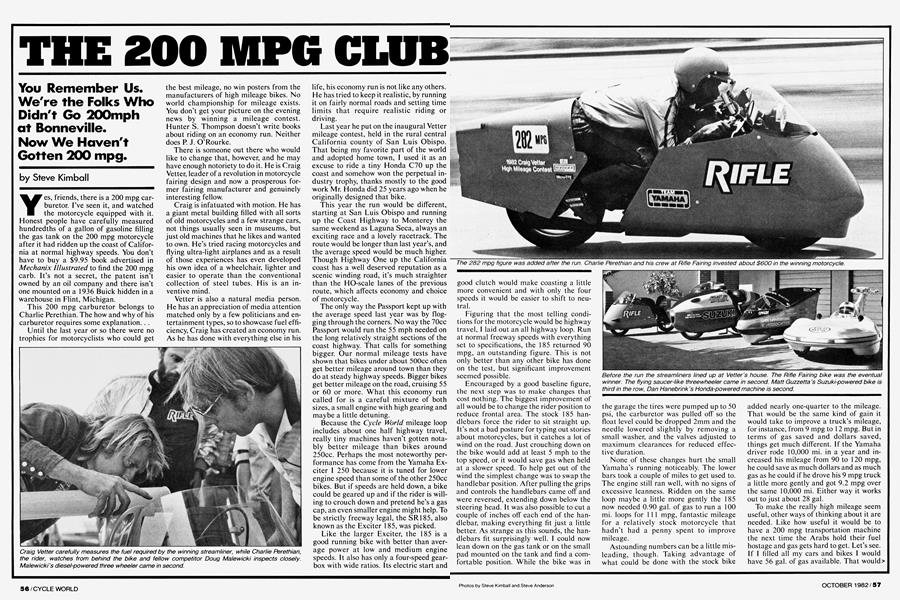

All the industry-class motorcycles were gathering at Vetter’s the afternoon before the economy run to show off their efforts, spy at the competition and tell the other guys how stock their own machines were. Vetter had his own semi-enclosed, laidback, touring economy cycle. It wasn’t running when he tried to start it, so it was pushed the rest of the way up the hill. A loose ignition cam screw turned out to be the problem. Perethian and his crew from Rifle Fairings were in early. Just parked in the shade it looked like a winner. Not having access to a wind tunnel, Perethian talked to the head of the aeronautical engineering school at Cal Poly, the local university. From that he determined the streamliner should have the smallest frontal area possible, be kept low so the center of pressure didn’t get too high and make the machine unstable, and have a gently tapering tail behind the full dustbin-style fairing. Not only did it look streamlined, it was easy to sit on, having a normal enough roadracer-type crouch for the rider. It still had good steering lock, all the controls worked normally and, except for the high gearing, it was about the same to ride as my stock, unfaired 185 Yamaha.

Doug Malewicki showed up with his diesel-powered tricycle, driven by Lynn Tobias, the president of the International Human Powered Vehicle Association. The diesel trike competed last year and has run a number of other mileage demonstrations, usually getting somewhere around 150 mpg, so it couldn’t be considered one of the bigger threats of the event, unless that frightful-sounding banging-and-popping thing inside the sleek fiberglass shell exploded.

Guzzetta showed up next with the Suzuki-based streamliner. This was a much larger device than the Rifle ‘liner. It was tall, had probably twice as much frontal area, was nicely shaped and looked very comfortable, A nice big little bike, it didn’t look quite the threat I had anticipated, but it looked practical enough to finish the run, something that couldn’t be said about all the entries.

That brings us to Dan Hanebrink. Hanebrink had made a variety of genuine nutball vehicles that might have been amazingly economical if the bugs had been worked out. Last year he showed up with three tiny pods, powered by weedeater motors and built around bicycle chassis. A couple of weeks before this year’s run he brought up his tiny machines and attacked the course, discovering that his powered bikes couldn’t finish the course in a reasonable amount of time. With a couple of weeks to work he came up with a completely new machine, powered by a small Honda four-stroke engine, looking as streamlined as a raindrop. It was obviously faster than the old bicycle-based ’liners, and it proudly proclaimed on the nose of the new bike a drag coefficient of 0.11. It was a full streamliner, all enclosed with a sliding bubble top and a tail that looked too high to survive the expected winds of the course. It was about half a mile outside the left field fence, but much closer than previous Hanebrink efforts and it looked as if it would finish the course this year.

One streamliner didn’t show up at Craig’s house Friday. That was Honda, about which everyone had heard indirect rumors, but which no one had seen. Last year the Honda streamliner was based on a fully enclosed shell originally made for human powered two-wheelers. It had some connection in design to Paul Van Valkenbuirgh, though he claimed no part in the venture. Paul, in fact, is very knowledgeable about small streamlined vehicles and has questioned whether some of the more extreme streamliners would be stable on a real road course.

A lady from the local television station showed up and asked questions like, “What’s your strategy this year?” Strategy? Here I am, sitting on the bench, and she’s asking about strategy. Maybe I’ll hide in the bushes alongside the road and throw rocks at the other bikes.

After a leisurely pre-race conference, the gathering broke up. I followed Perethian and his crew back to the Rifle fairing shop where we made last minute changes on the bikes and took time out to watch the six o’clock news and see ourselves interviewed on the electric television. In typical TV news fashion, all the good comments were cut and I looked like the hero of an Alka-Seltzer commercial.

Back to the bikes. Charlie was creating plexiglass sidecurtains to clean up the shape of the streamliner just a little more. I found a smaller rear sprocket, a 34-tooth, and figured that if a little bit was good, a little more was better, and hammered it into place. A last-minute check showed everything was set, except that the rear tire was low. Oh, well, not to worry.

The next morning at the sign-in the tire was low again. A more careful look still didn’t turn up any sounds or sights of damage and I installed a new valve core just to make sure. It seemed to be holding.

Honda showed up in typical Honda fashion. A giant van opened up and a crew of dozens rolled out the streamliner. It was taller than the others, with a large, windowed cantilevered canopy enclosing the cockpit. Built around a CB125 engine and with enormously tall gearing, it looked as though it could get 300 mpg. At least as long as there were no side winds it might get 300. The side area was like a billboard. The center of pressure was obviously way above the center of gravity, just as it had been the previous year. Van Valkenburgh was right, I thought. This will never survive.

To make sure their effort survived, Honda had hired a professional trials rider, Debbie Evans, to ride the streamliner. A wonderfully talented rider, she would certainly do as good a job balancing the streamliner as anyone available, plus adding the least weight and looking pretty in the film that Honda would no doubt produce. As the crew fastened her into the cockpit and connected two-way radios so she could communicate with the chase van and crew, other competitors crowded around and took pictures.

On the other side of the parking lot Brenda Wilvert was rolling her tiny Kawasaki AR80 through tech inspection. Brenda works at Kawasaki, not as a motorcycle rider but she likes to ride bikes. So a week before the run she talked her bosses into breaking an AR80 out of the crate so she could run it in the mileage contest. Nobody was crowding around the Kawasaki taking pictures. Small two-strokes aren’t efficient, everyone knows, and this was a purely stock bike, barely broken in, ridden by a desk-jockey no one had ever heard of.

Just before leaving on the run I saw Jim Wolcott from Road Rider magazine on a Honda XL 185. Not having titles to our borrowed bikes, we agreed on competing for a beer. TV cameras were running as I left the starting line, had the engine die, started up again and ran down the driveway to a signal that stayed red for at least two minutes and probably longer, though I couldn’t testify about that.

There were no highway patrolmen lurking in the bushes as the various bikes, several too small to be legal on the freeway, headed up the short stretch of Highway 101 through San Luis. Halfway through town our route sheet guided us off the freeway and onto Highway 1, the Coast Highway.

If there is a motorcyclist who hasn’t heard of Highway 1, I haven’t met him. California’s Coast Highway is the archtype scenic road. It has been shown in countless movies where heroes chased bad guys, raced to meet girl friends, or just looked at colorful sunsets while riding along the gentle winding highway. This is the road to Hearst’s Castle, where William Randolph Hearst created his monument to conspicuous consumption and entertained the most important people of his generation.

Vetter preran the course several times on a variety of motorcycles and set a time limit accordingly. Two hours and 43 min. were needed to run the route at a normal pace, 55 mph on the straights, no delay and no special hurry. To provide plenty of flexibility, a 15 min. window allowed riders enough leeway so none would be disqualified without cause, while requiring a reasonable pace for the contest. A route sheet showed landmarks with the time necessary to ride to those spots, so entrants could judge if they were running ahead or behind schedule.

continued on page 76

continued from-page 61

Given such leeway, I expected to use the 15 min. grace period for going slower than required. Without streamlining, the little Yamaha was sensitive to speed, sacrificing extra fuel to keep running 55 or 60 up hills or into headwinds. The coast was a surprise for the economy run. During the summer it is almost always shrouded in a heavy, cold fog. This year it was clear. Thanks to the 7 a.m. start, the traffic was light, too. Instead of cruising at 55 mph I went 50 mph on most of the level stretches, speeding up slightly going downhill and slowing more up hills. The southern sections of the road are mostly straight with a few gentle corners, so I expected to lose more time here, and make it up through the tighter sections.

At the first checkpoint everything was going well and the Yamaha was only 2 min. behind schedule. Even dropping 2 min. each checkpoint would only put me down 8 min. at the end, right at the middle of the window, so I continued at the same pace. No one passed me or got in my way; most of the riders must have been running about the same speed.

Still 2 min. behind at the second checkpoint, it looked as though I could slow down even more. Curves up ahead and a slowly rising sun made the big, slow four and six-wheeled boxes come out from their hiding places beside the road and plug the highway. Passing wasn’t difficult for the 185 because it still could accelerate faster than most cars and didn’t have any trouble with the corners, though it was feeling less than its usual self. A glance at the back tire showed why. It was slowly losing pressure again, though it still had enough to keep the rim off the pavement. Not having a patch kit along made it easy to decide to finish the run with low air pressure.

Farther up the coast the campers and cars were more numerous and harder to pass. A few were going almost as fast as the average speed of this economy run, though passing them at the earliest opportunity kept them from slowing me down on the downhills and corners.

Only at the last quarter of the run did the wind pick up. A headwind had been anticipated for the run, one of the reasons I left as early as possible. But the wind at the north end of the course came in straight off the ocean, making for a fine crosswind. Depending on how soon the streamliners left, I might have enough time to come back to this windswept, winding area and take pictures of streamliners being blown off the road, I thought.

The wind hardly bothered the little Yamaha at all, but it had little side area. This wasn’t one of the stronger crosswinds I’d encountered on this road, but it was enough to make the ride more interesting. Mostly all it did to the Exciter was require a lower gear when headed directly into the wind.

More traffic backed up close to the finish line, and with plenty of time to spare, I slowed and followed the line of vacationers into Carmel, where the route turned off at the first stoplight and ended at an Arco station. A half dozen motorcyclists had left and finished ahead of me, and others were arriving just behind. The organization was efficient. A welcoming committee wrote the incoming time on the time sheet, others guided the bike to the pump where Dick Arnold was in charge of filling the tanks, each one to the lowest spot on the filler neck, the same as they had been filled at the start, before the tanks were sealed with glue.

As the pump clicked off about a gallon of gas I waited for it to stop, expecting the taller gearing to help more than the nearly flat rear tire and headwind hurt. It kept running. Another tenth. Then another. Just before a gallon and a half it stopped, the tank filled the same as it had been before. Ninety-two lousy miles per gallon, my calculator said. That was worse than any mileage the bike got running up the freeway at 65 mph. It was worse than the previous year’s Passport got.

About that time Jim came in on the small Honda. He used a couple of tenths of a gallon more, earning me a beer, if not a trophy. A fellow with a Gold Wing was asking everyone what they got, then gloating when he could boast that his GL beat them by getting 60 mpg. I pulled the Yamaha to one side and pulled the back wheel to patch the rear tube. There was a tiny staple hidden in the tread, and a tiny easily patched hole in the tube. The guy at the station patched it for free.

Brenda Wilvert came in on the screaming green AR80 Kawasaki. The pump stopped surprisingly soon on that, giving her 112 mpg, the best mileage seen so far.

At about the same time, Perethian came in, followed by his wife riding the family BMW as the backup bike, then followed by Craig on his bike and what was left of the Honda streamliner, followed closely by the big, white van filled with people wearing Honda shirts. The Honda crashed when it ran into the wind, enough to destroy the top of the enclosure and scrape the rider’s elbow, but not causing any serious injury. After that, she said, it was more controllable. Hanebrink also came in looking more scraped up than he was at the beginning.

The diesel crew provided a graduated cylinder for filling the streamliners and a large crowd poured around the tiny ’liners as they were filled. It only took 0.491 gal. (76.3 cents) to fill the Honda after 136 mi. of riding and crashing, for 276.78 mpg. (The chase van wasn’t filled there.)

Perethian’s Yamaha took 0.482 gal. (three quarters worth of gas) to carry him to Monterey. Mileage was 282.15 mpg, even better than the Honda. Would it be the best?

Hanebrink’s streamliner took 0.572 gal for 237.8 mpg. Both Hanebrink and the Honda came in over the time limit as the result of delays from crashing.

Official second place went to Lynn Tobias in the three wheeler with 169.79 mpg, just ahead of Guzzetta in the Suzuki with 152.31 mpg. Both reported difficult con trol in the wind. Last place among the streamliners went to Craig with only 108.19 mpg.

As it turned out Brenda Wilvert was the top privateer on the tiny Kawasaki. She won $600. Among the various class winners was Dan Wilson who bought a wrecked Kawasaki KL250 for $100, put on a $3 used tire and some handlebars and got 102.9 mpg, winning $300.

Craig’s goal of 200 mpg was easily surpassed, though only one bike finishing within the time limit beat that. The results show that the route is a good determinate of practicality. Not just anything with two wheels and a motor can finish it, yet virtually any stock bike would have no trouble. The course requires the same combination of handling ease, stability, power and brakes that any bike would need to be safely operated on a regular basis.

But a practical 200 mpg motorcycle can and has been built. It doesn’t have a secret carburetor. It isn’jt unstable in sidewinds. It is reliable and easy to ride. The secret of such incredible mileage is a small frontal area, with a clean aerodynamic shape, powered by virtually any relatively stock small motor geared as tall as possible

Several sources have figured out that a properly designed streamliner needs about 1.5 bhp to sustain 60 mph. Current good gasoline-fueled engines use about 0.45 lb. of fuel per horsepower-hour. That works out to a theoretical maximum mileage of just over 500 mpg for a well-built streamliner at freeway speeds.

That’s'in theory. There are good minds at work here. Before this year’s bikes were finished, most of the teams knew what they were going to try for next year. There are better shapes, and more efficient ways to run engines.

What this year taught the entrants and should teach the world is that motorcycles can be a lot more efficient, that they’re already much better than any other useful means of travel, and that it’s fun to find out how much motorcycling can be squeezed from a gallon of fuel.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAdvice To the Lovelorn

October 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1982 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1982 -

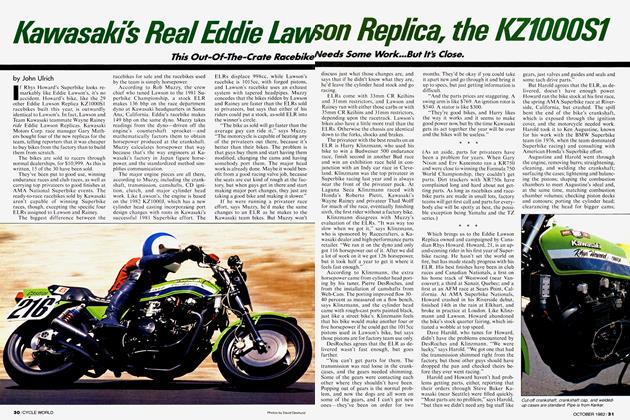

Competition

CompetitionKawasaki's Real Eddie Law Son Replica, the Kz1000s1

October 1982 By John Ulrich -

Features

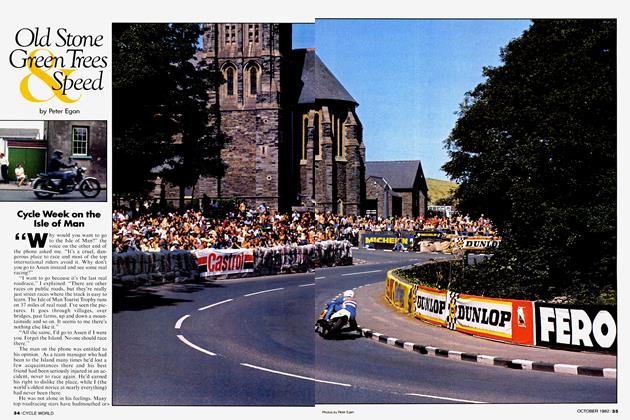

FeaturesOld Stone Green Trees & Speed

October 1982 By Peter Egan -

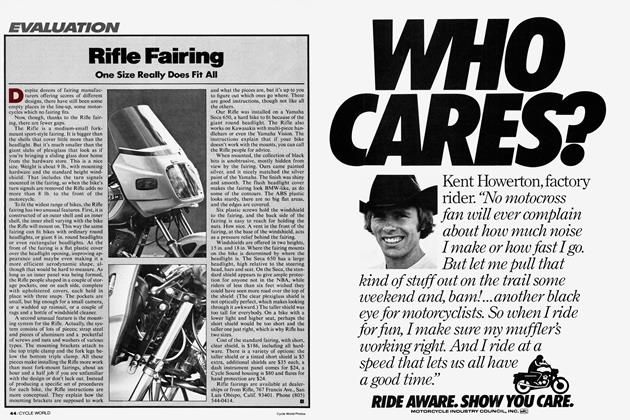

Evaluation

EvaluationRifle Fairing

October 1982