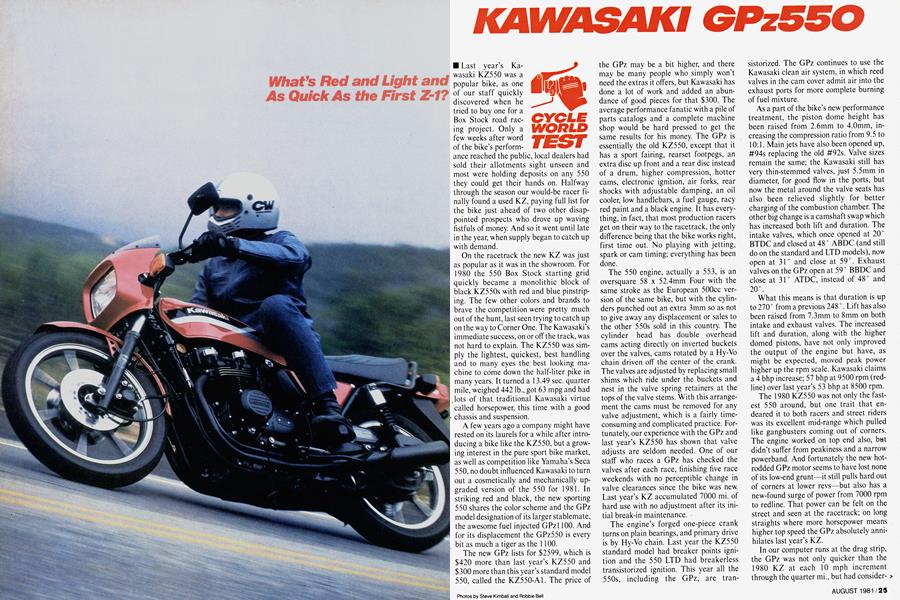

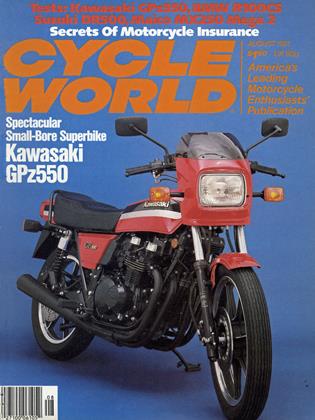

What's Red and Light and As Quick As the First Z-1?

KAWASAKI GPz550

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Last year's Kawasaki KZ550 was a popular bike, as one of our staff quickly discovered when he tried to buy one for a Box Stock road racing project. Only a few weeks after word of the bike's performance reached the public, local dealers had sold their allotments sight unseen and most were holding deposits on any 550 they could get their hands on. Halfway through the season our would-be racer finally found a used KZ, paying full list for the bike just ahead of two other disappointed prospects who drove up waving fistfuls of money. And so it went until late in the year, when supply began to catch up with demand.

On the racetrack the new KZ was just as popular as it was in the showroom. For 1980 the 550 Box Stock starting grid quickly became a monolithic block of black KZ550s with red and blue pinstriping. The few other colors and brands to brave the competition were pretty much out of the hunt, last seen trying to catch up on the way to Corner One. The Kawasaki's immediate success, on or off the track, was not hard to explain. The KZ550 was simply the lightest, quickest, best handling and to many eyes the best looking machine to come down the half-liter pike in many years. It turned a 13.49 sec. quarter mile, weighed 442 lb., got 63 mpg and had lots of that traditional Kawasaki virtue called horsepower, this time with a good chassis and suspension.

A few years ago a company might have rested on its laurels for a while after introducing a bike like the KZ550, but a growing interest in the pure sport bike market, as well as competition like Yamaha's Seca 550, no doubt influenced Kawasaki to turn out a cosmetically and mechanically upgraded version of the 550 for 1981. In striking red and black, the new sporting 550 shares the color scheme and the GPz model designation of its larger stablemate, the awesome fuel injected GPzl 100. And for its displacement the GPz550 is every bit as much a tiger as the 1100.

The new GPz lists for $2599, which is $420 more than last year's KZ550 and $300 more than this year's standard model 550, called the KZ550-A1. The price of

the GPz may be a bit higher, and there may be many people who simply won't need the extras it offers, but Kawasaki has done a lot of work and added an abundance of good pieces for that $300. The average performance fanatic with a pile of parts catalogs and a complete machine shop would be hard pressed to get the same results for his money. The GPz is essentially the old KZ550, except that it has a sport fairing, rearset footpegs, an extra disc up front and a rear disc instead of a drum, higher compression, hotter cams, electronic ignition, air forks, rear shocks with adjustable damping, an oil cooler, low handlebars, a fuel gauge, racy red paint and a black engine. It has everything, in fact, that most production racers get on their way to the racetrack, the only difference being that the bike works right, first time out. No playing with jetting, spark or cam timing; everything has been done.

The 550 engine, actually a 553, is an oversquare 58 x 52.4mm Four with the same stroke as the European 500cc version of the same bike, but with the cylinders punched out an extra 3mm so as not to give away any displacement or sales to the other 550s sold in this country. The cylinder head has double overhead cams acting directly on inverted buckets over the valves, cams rotated by a Hy-Vo chain driven off the center of the crank. The valves are adjusted by replacing small shims which ride under the buckets and nest in the valve spring retainers at the tops of the valve stems. With this arrangement the cams must be removed for any valve adjustment, which is a fairly timeconsuming and complicated practice. Fortunately, our experience with the GPz and last year's KZ550 has shown that valve adjusts are seldom needed. One of our staff who races a GPz has checked the valves after each race, finishing five race weekends with no perceptible change in valve clearances since the bike was new. Last year's KZ accumulated 7000 mi. of hard use with no adjustment after its initial break-in maintenance.

The engine's forged one-piece crank turns on plain bearings, and primary drive is by Hy-Vo chain. Last year the KZ550 standard model had breaker points ignition and the 550 LTD had breakerless transistorized ignition. This year all the 550s, including the GPz, are tran-

sistorized. The GPz continues to use the Kawasaki clean air system, in which reed valves in the cam cover admit air into the exhaust ports for more complete burning of fuel mixture.

As a part of the bike's new performance treatment, the piston dome height has been raised from 2.6mm to 4.0mm, increasing the compression ratio from 9.5 to 10:1. Main jets have also been opened up, #94s replacing the old #92s. Valve sizes remain the same; the Kawasaki still has very thin-stemmed valves, just 5.5mm in diameter, for good flow in the ports, but now the metal around the valve seats has also been relieved slightly for better charging of the combustion chamber. The other big change is a camshaft swap which has increased both lift and duration. The intake valves, which once opened at 20° BTDC and closed at 48° ABDC (and still do on the standard and LTD models), now open at 31° and close at 59°. Exhaust valves on the GPz open at 59 ° BBDC and close at 31° ATDC, instead of 48° and 20°.

What this means is that duration is up to 270 ° from a previous 248 °. Lift has also been raised from 7.3mm to 8mm on both intake and exhaust valves. The increased lift and duration, along with the higher domed pistons, have not only improved the output of the engine but have, as might be expected, moved peak power higher up the rpm scale. Kawasaki claims a 4 bhp increase; 57 bhp at 9500 rpm (redline) over last year's 53 bhp at 8500 rpm.

The 1980 KZ550 was not only the fastest 550 around, but one trait that endeared it to both racers and street riders was its excellent mid-range which pulled like gangbusters coming out of corners. The engine worked on top end also, but didn't suffer from peakiness and a narrow powerband. And fortunately the new hotrodded GPz motor seems to have lost none of its low-end grunt—it still pulls hard out of corners at lower revs—but also has a new-found surge of power from 7000 rpm to redline. That power can be felt on the street and seen at the racetrack; on long straights where more horsepower means higher top speed the GPz absolutely annihilates last year's KZ.

In our computer runs at the drag strip, the GPz was not only quicker than the 1980 KZ at each 10 mph increment through the quarter mi., but had considerably more hustle in top gear roll-ons. It knocked 0.2 sec. off the 40 to 60 mph time and a full second off the 60 to 80 mph roll on. Those are figures that have real meaning when you're passing motor homes on an uphill two-lane.

This kind of comparison also shows up at the drag strip, of course. Our GPz turned a remarkable 12.65 sec, at 104.16 mph. That's a 550 class record.

It's more than that. The 1980 KZ550 turned 13.49 sec. at 95.23 mph. Our 1981 Seca 550 had a best of 12.99 sec. at 98.57 mph. The GPz out-does a bunch of 650s, like the Yamaha Midnight Maxim, and some 750s, like Honda's CB750C.

The GPz out-performs Kawasaki's legendary 500 Mach III two-stroke Triple, which ran a 13.20 sec. at 100.22 mph in 1969, and most impressive of all, the 550 GPz is virtually as quick as the original

Kawasaki 900 Z-l, which turned a 12.61 sec.—only 0.04 sec. quicker than the GPz—in 1972. Amazing.

But this sort of quantum leap is normal these days. The GPz has power on the Seca 550 but in the road races both bikes are so good and so close in all-around performance that a well-prepared, well-ridden example of either machine is capable of beating the other.

The Kawasaki might be even quicker through the traps if it had slightly lower gearing. Instead of gearing down, as is often done when manufacturers are searching for good ETs, Kawasaki has geared the 550 up, dropping the rear wheel sprocket from 40 to 38 teeth. The GPz is therefore pulling a 5.93 6th gear, as compared with a 6.25 ratio last year, and this in turn means the engine speed at 60 mph has dropped from 4902 rpm to 4750.

That slightly more relaxed cruising rpm is a bonus for street and touring riders as it makes for a less hectic-sounding engine at highway speeds, but it makes 6th gear too tall to be really useable on the race track. Performance buffs, of course, can always drop a tooth on the front sprocket or use a bigger rear sprocket to make the power multiplication a little more favorable, while everyone else can enjoy the advantages of the longer-legged stock gearing. The combination of well-spaced ratios in the six-speed transmission along with the bike's solid mid-range will leave few riders groping for gears they need but can't find.

In fact, the only gear that is ever hard to find on the 550 is 2nd. The GPz has a ball lockout system on the engagement dogs so that when the bike is at a standstill an upshift from 1st will always give you neutral rather than an accidental 2nd. That1 way you don't have to play footsie with the shift lever while searching for the neutral light at stop signals. The only disadvantage here is there's no way to engage 2nd gear for a bump start if the battery goes dead; the bike has to be rolling, engine running. Except for that drawback, the transmission works beautifully, free from notchiness, false neutrals and missed shifts.

The keen of eye will notice on the spec chart that the new GPz weighs 460 lb. with half a tank of gas, and the long of memory will recall that the 1980 KZ weighed only 442 lb. While such small incidentals as the fairing, gas gauge and rearsets may have added a pound or two, most of the weight increase is due to the triple disc brakes. And those who rode the KZ in combat last year will probably regard the weight as well-spent. There was no particular complaint with the rear drum, but the front disc had a slightly mushy feel under hard braking. This was traced to the front caliper, which could be seen to flex outward when the brake lever was squeezed hard. The single disc worked pretty well, especially if the stock pads were replaced with KZ650 pads, but the softness of the lever didn't inspire the same confidence as the rest of the otherwise firm, mechanical feeling KZ. The softness is gone from the new double discs; they simply work. Lever feel is firm, the effort-to-stopping ratio is progressive, and the easily controlled front brakes allow you to dive deep into corners and get on the lever hard without the unpleasant surprise of wheel lockup or road shortage. The GPz stopped six feet shorter than the single disc 1980 KZ, with 18 lb. of added weight.

Both the GPz and the 1981 KZ550 now have air forks. There is no crossover tube so each leg is filled separately through a valve hidden under a rubber dust cap at the top of the fork leg. When we first picked up our test bike one rider immediately complained of brake dive and a slight hobby-horse tendency over road:* seams. The forks had just under the 8.5 psb minimum recommended pressure, so we tried it at the maximum setting of 11.4 psi (or as close as we could get to it; might be 11.3 by now). At maximum pressure brake dive is greatly reduced, the hobby-^ horse feel gone, and yet the front suspension is compliant over rough surfaces and, stable in fast corners. On the race track, where the road surface is relatively smooth, 15 to 17 psi seems to work best.

The rear shocks have four damping adjustments and are easily set by rotating the chromed collar at the top of each'1 spring. Our bike felt best with the spring preload set on bottom or second notch and the shocks on full damping. The shocks do a perfectly good job of damping for fast road work, though our club racer found they faded after a few laps of fast bumpy turns, like Willow Springs' Turn Eighth and began to cause some wallowing problems. He replaced them with a set of S&W street shocks and the problem went away.

Steering geometry is identical to that on last year's KZ; i.e. quick and steep. With 26° of rake and 3.9 in. trail, combined with the Kawasaki's 54.9 in. wheelbase,* you won't have time for a cup of coffee or a cigarette after flicking the GPz into a corner. It goes where directed, when directed. Steering is quick and precise, and only small movements and changes of balance are needed to guide the 550 in and out of S-bends. An unexpected plus in the GPz's handling composure is its excellent directional stability despite the rather steep* fork angle. Whether the steering is deflected by a road obstacle like a rock or by a sudden correction for rear end slide on a loose surface, it has a remarkable ability to center itself quickly and continue down the road as though nothing had happened. In airplanes this is known as a “forgiving”^ trait. You have to get really crossed up in a corner or hit something fairly slippery to induce the 550 to drop you on your ear or assume a point-of-no-return attitude. This doesn't mean you can't make mistakes and run off the road; it just means the bike will do its best to stay upright and on the pavement.

Cornering clearance on the GPz is very, good for normal-to-slightly crazy riding, though pushed hard the Kawasaki will ground various hard parts on both sides. In a fast sweeper the right footpeg, then entire length of the brake lever, then exhaust pipes will touch down; in left turns it's the^ footpeg and then the sidêstand bracket. The sidestand bracket can make an abrupt and solid contact with the pavement in really hard cornering, and most competition riders end up grinding it down on the track or in the shop. Most street riders will be in more danger from oncoming traffic than from protruding hardware before they go fast enough to ground anything significant on the GPz's undercarriage.

Starting the motorcycle on cool or warm mornings, or any other time the bike has been sitting for more than half an hour, demands full choke. Until the bike is warmed up, choke and throttle need a bit of fussing to keep the engine running smoothly. Full choke starts the engine, but has to be reduced slightly right away or the engine goes over-rich and sputters. From there it needs a steady but gradual movement of the choke lever to keep the engine running properly as it warms up. During the first five minutes of riding the engine will stagger if the choke is set a littler over-rich or lean, but will come on with a kick-in-the-pants surge of power when you get it just right. Once warm, the GPz provides the rider with the uncommon joy of perfect throttle response. There is no lag or sputter at any throttle opening. Whack the throttle open at low rpm and the 550 responds with solid, willing acceleration and no sign of detonation; downshift to get the revs up and that same open throttle goes into sling-shot mode and provides a spirited rush of revs and acceleration right up to redline. And the gears are closely enough spaced that shifting up from redline will keep you firmly in the hard-working power band. The four 22mm TK slide-throttle carbs do their job well.

They also manage to be very stingy when it comes to doling out fuel to the engine. Our 1980 KZ got a miserly 63 mpg on our test loop, so we naturally expected the new high-performance GPz to Jail well short of that figure. Our fears were confirmed; the GPz gets only 62.3 mpg—a whopping 0.7 mpg loss. Who says you don't pay for horsepower? This mileage was measured on a 100 mi. loop of average street and highway riding, of course, which does not keep the engine hyped up into the hot and thirsty end of its ^powerband. But even on fast mountain rides we were able to drive mileage down only into the mid 40s, which won't be causing any enthusiasts to cancel the Sunday morning ride because of high fuel costs. The tank holds 3.8 gal., half a gallon of which is reserve, so a range of 170 to 200 mi. is possible before reserve is needed, depending on riding verve. The GPz has a small fuel gauge mounted at the top of the instrument cluster, which eliminates the need to peer into and shake the tank. Our test bike's gauge liked to stick on a reading of full-and-one-quarter »for about the first 25 mi. of each tank, but was accurate once it started to move downward. The gas cap is our favorite type, hinged and non-dropable.

The GPz's seat has been redesigned with flashier stitching, but not much detectable change in padding. The seat is no .luxury cushion, but is comfortable enough as sport saddles go. Any soreness GPz riders suffer will come from spending too much time in the saddle rather than from any failing of the seat. Footpegs, now rearset, are actually lower to the ground than

those on the standard KZ, but have been moved back and inward so cornering clearance is slightly improved. The new pegs, along with the GPz's low sport bars, put the rider in an excellent position for both highway cruising and Ticking the bike down winding roads.

At last-—at long last—after years of grumbling and gnashing of teeth, sport riders are finally able to buy a few models of bikes right off the showroom floor with handlebars that don't poke you in the shoulders and footpegs that aren't six inches ahead of your knees. Kawasaki deserves (and will no doubt get) praise for the control layout on both their GPz models, the 1100 and the 550. They, along with the 550 Seca, the Suzuki 450S and the CBX now number among the few Japanese sport bikes we are able to ride comfortably without immediately throwing the handlebars away.

The comfortable riding position and small size of the 550 make it an attractive choice for running errands around town, when it isn't being used on country roads or the open highway. The engine can get a bit buzzy near redline, but for anything but banzai attacks on the pavement the vibration level is low and doesn't gnaw at the feet and hands. The small bikini fairing, as you would expect, doesn't overwhelm anyone with wind-free weather

protection, but it does take some of the wind pressure and cold air off the rider's torso, and it does so without concentrating a hard blast of air right in the face shield as some small fairings do. It seems to diffuse the air flow fairly well, while making cool weather riding just a little more comfortable.

The instruments are easy to read, control switches and buttons well-placed and clutch pull is light. Overall, the GPz is a comfortable, easy to handle bike. And that is the amazing thing about the new sporting middleweights like the GPz, or the Yamaha 550 Seca. In an earlier generation of motorcycles 500 class bikes approaching this kind of performance would have been cranky, hard to start, thirsty, short-lived machines with lumpy idle characteristics and engines that liked to spit back through the carbs. Instead, we now have the Kawasaki GPz550, a hot rodded version of what was already a high performance bike, and it has none of those problems. The bike is smooth at idle, docile around town, easy on fuel and, from what we've seen so far, nearly unbreakable. If there is any price to be paid for the 550's extra power, it is only that added $300 out the door. After that it's free. The GPz offers a lot of what the first Kawasaki Z-l had going for it; performance without the sacrifice of civility.

KAWASAKI GPz550

$2599

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontA Satisfied Mind

August 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1981 -

Book Review

Book ReviewBrooklands Behind the Scenes

August 1981 By Henry N. Manney III -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

August 1981 -

Motorcycle Insurance

Motorcycle InsuranceWhat It All Means, And How To Know What You Need.

August 1981 By David D. Mallet -

Motorcycle Insurance

Motorcycle InsuranceNot All Motorcycle Insurance Companies Are Alike. Some Take Your Money And Go Out of Business.

August 1981 By John Ulrich