ROAD RACING

COMPETITION GUIDE

Road racing has its roots in races held on real, honest-to-goodness roads through towns and across the countryside. Nowdays a few races on true street circuits still exist but because public roadways are typically lined with all manner of hard objects for errant racers to run into (like houses, street lamps, etc.) most road races are now run on purpose-built racetracks.

Those tracks vary in length and design, some providing the racer with lots of runoff room (or space to stop in after running off the track), some closely lined with the deadly Armco barriers preferred by automobile racers. But they're all on pavement, usually asphalt.

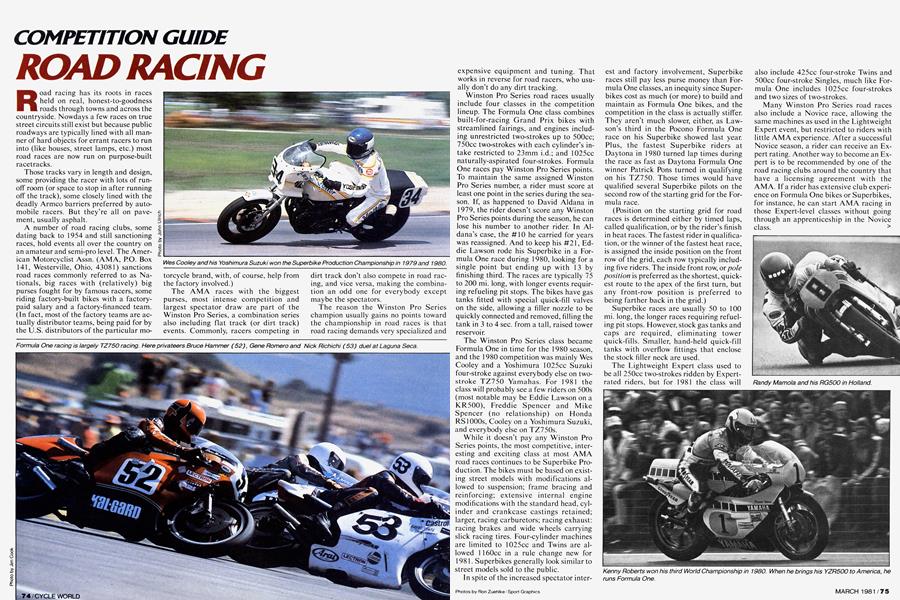

A number of road racing clubs, some dating back to 1954 and still sanctioning races, hold events all over the country on an amateur and semi-pro level. The American Motorcyclist Assn. (AMA, P.O. Box 141, Westerville, Ohio, 43081) sanctions road races commonly referred to as Nationals, big races with (relatively) big purses fought for by famous racers, some riding factory-built bikes with a factorypaid salary and a factory-financed team. (In fact, most of the factory teams are actually distributor teams, being paid for by the U.S. distributors of the particular motorcycle brand, with, of course, help from the factory involved.)

The AMA races with the biggest purses, most intense competition and largest spectator draw are part of the Winston Pro Series, a combination series also including flat track (or dirt track) events. Commonly, racers competing in

dirt track don't also compete in road racing, and vice versa, making the combination an odd one for everybody except maybe the spectators.

The reason the Winston Pro Series champion usually gains no points toward the championship in road races is that road racing demands very specialized and expensive equipment and tuning. That works in reverse for road racers, who usually don't do any dirt tracking.

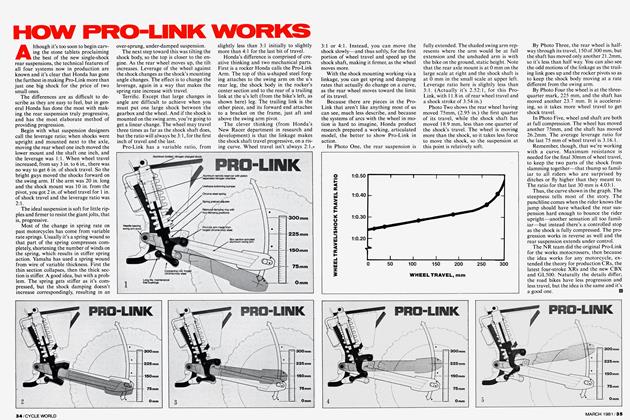

Winston Pro Series road races usually include four classes in the competition lineup. The Formula One class combines built-for-racing Grand Prix bikes with streamlined fairings, and engines including unrestricted two-strokes up to 500cc; 750cc two-strokes with each cylinder's intake restricted to 23mm i.d.; and 1025cc naturally-aspirated four-strokes. Formula One races pay Winston Pro Series points. To maintain the same assigned Winston Pro Series number, a rider must score at least one point in the series during the season. If, as happened to David Aldana in 1979, the rider doesn't score any Winston Pro Series points during the season, he can lose his number to another rider. In Aldana's case, the #10 he carried for years was reassigned. And to keep his #21, Eddie Lawson rode his Superbike in a Formula One race during 1980, looking for a single point but ending up with 13 by finishing third. The races are typically 75 to 200 mi. long, with longer events requiring refueling pit stops. The bikes have gas tanks fitted with special quick-fill valves on the side, allowing a filler nozzle to be quickly connected and removed, filling the tank in 3 to 4 sec. from a tall, raised tower reservoir.

The Winston Pro Series class became Formula One in time for the 1980 season, and the 1980 competition was mainly Wes Cooley and a Yoshimura 1025cc Suzuki four-stroke against everybody else on twostroke TZ750 Yamahas. For 1981 the class will probably see a few riders on 500s (most notable may be Eddie Lawson on a KR500), Freddie Spencer and Mike Spencer (no relationship) on Honda RSI000s, Cooley on a Yoshimura Suzuki, and everybody else on TZ750s.

While it doesn't pay any Winston Pro Series points, the most competitive, interesting and exciting class at most AMA road races continues to be Superbike Production. The bikes must be based on existing street models with modifications allowed to suspension; frame bracing and reinforcing; extensive internal engine modifications with the standard head, cylinder and crankcase castings retained; larger, racing carburetors; racing exhaust: racing brakes and wide wheels carrying slick racing tires. Four-cylinder machines are limited to 1025cc and Twins are allowed 1160cc in a rule change new for 1981. Superbikes generally look similar to street models sold to the public.

In spite of the increased spectator inter-

est and factory involvement, Superbike races still pay less purse money than Formula One classes, an inequity since Superbikes cost as much (or more) to build and maintain as Formula One bikes, and the competition in the class is actually stiffen They aren't much slower, either, as Lawson's third in the Pocono Formula One race on his Superbike showed last year. Plus, the fastest Superbike riders at Daytona in 1980 turned lap times during the race as fast as Daytona Formula One winner Patrick Pons turned in qualifying on his TZ750. Those times would have qualified several Superbike pilots on the second row of the starting grid for the Formula race.

(Position on the starting grid for road races is determined either by timed laps, called qualification, or by the rider's finish in heat races. The fastest rider in qualification, or the winner of the fastest heat race, is assigned the inside position on the front row of the grid, each row typically including five riders. The inside front row, or pole position is preferred as the shortest, quickest route to the apex of the first turn, but any front-row position is preferred to being farther back in the grid.)

Superbike races are usually 50 to 100 mi. long, the longer races requiring refueling pit stops. However, stock gas tanks and caps are required, eliminating tower quick-fills. Smaller, hand-held quick-fill tanks with overflow fittings that enclose the stock filler neck are used.

The Lightweight Expert class used to be all 250cc two-strokes ridden by Expertrated riders, but for 1981 the class will also include 425cc four-stroke Twins and 500cc four-stroke Singles, much like Formula One includes 1025cc four-strokes and two sizes of two-strokes.

Many Winston Pro Series road races also include a Novice race, allowing the same machines as used in the Lightweight Expert event, but restricted to riders with little AMA experience. After a successful Novice season, a rider can receive an Expert rating. Another way to become an Expert is to be recommended by one of the road racing clubs around the country that have a licensing agreement with the AMA. If a rider has extensive club experience on Formula One bikes or Superbikes, for instance, he can start AMA racing in those Expert-level classes without going through an apprenticeship in the Novice class.