"What a lovely machine!” said the little old lady in the little old English car. “Harley-Davidson, is it? I’ve heard of them. And you’re going to the TT races? Ooh, I went there in my younger days. Why, I’d climb right on the back and go with you now if"—and here I began thinking of saying I wish I’d met her when I was younger, but she fooled me—"It wasn’t for this broken leg.

“Mad keen on speed, that’s my problem.”

England. Whether there will always be an England is a question for history, but the sure bet is that England will always be, well, English. Mad keen on speed and motorbikes, as the lady said.

That’s half the story. The other half begins in downtown Liverpool. Catch the boat early, they’d told me but they hadn’t told me just where the boat was. No problem. Soon as I rode away from the hotel I blended into a stream of bikes, all loaded for the road and all headed in the same direction, so I got into line—make that queue—and sure enough, there was the steam packet for the Isle of Man.

How long this has been going on, I didn’t have to ask. Seventy-five years. TT Week on the island is the oldest ongoing racing event in the world, and it’s that because England is England and the Isle of Man isn’t England.

TT Week is also a wonderful place to watch races but first, the background behind the wisecrack.

In the closing days of the 19th Century the industrial revolution had progressed to the point of allowing most people in England to take vacations. They all wanted to go to the beach. The Isle of Man heretofore had been a beautiful bit of land in the Irish Sea, appreciated mostly by Vikings and Monks and fishermen and smugglers and farmers who’d come up with their own language, a scramble of Gaelic, English and Norse if I read the road signs right. .. and their own government, which has run things there for 1000 years.

Enterprising people built steamers and boarding houses and great swarms of tourists came to visit. They brought money and the Manx decided this was a good thing.

Parallel to this came the invention of motor racing. There were competitions on ordinary roads, between teams from various countries. Feelings ran high and speeds went up and there came the day when the English had no place to host the events. To the rescue came the head man on the IoM, mad keen on speed, he was too. The Manx government, thanks to home rule and the Manx habit of not always doing what the English did, voted to allow racing on public roads. First cars, then bikes but because bikers are what they are, long after the cars settled for short circuits and controlled conditions the motorcycles were cranking ‘round the 37.75 miles of country road, city street and winding mountain passes, dotted with curbs and bridges and rock walls and cliffs that still, to some of us, mean road racing.

MAD KEEN ON SPEED

An Electra-Glide's View Of TT Week On the Isle Of Man

Allan Girdler

Which brings up part three. Ten or 15 years ago there arose objections to the IoM and racing on real roads. Too risky, said some, not enough money said others and as a group the Grand Prix riders pulled out. The rules changed and what had been a world championship event became a fraction of a world championships the TT Class with one race on the island and the other in Ireland.

The Manx and the motorcyclists reacted in their obstreperous way, that is, they don’t care what Barry and Kenny don’t allow, gonna race ‘round the island anyhow. The Auto Cycle Union, sort of like our AMA, sanctions and organizes the week-long racing. The Isle of Man Tourist Board puts up starting and prize money in amounts that would give U.S. promoters the blind staggers and the House of Keys, Manx’s government, votes to close the public roads for racing whenever needed. Try that in Congress or Parliament!

All the above was secondhand to me. All I knew was what I'd read in the racing papers, and heard on those records sold by none other than Cycle World some time ago (Not an advt, sorry to say, CW went out of the record business about the time MV quit racing.) TT Week was a myth, a legend and an ambition until the British classic racers came to Daytona and one of them, Alan Cathcart, who also writes for various publications and enjoyed being showm around American racing, said how would I like to come over for TT Week?

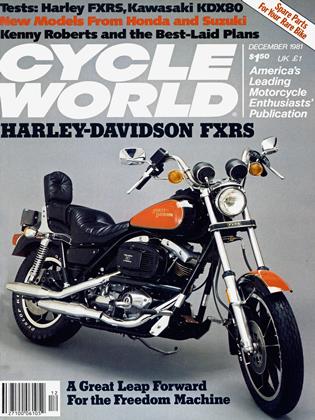

A lot, is how' I would like it. Overcome by common sense I said no to an offer of a ride for the old bike event, nor did I hit one of the factories for a sporting new machine. Instead I asked Malcolm Forbes, Biker/Balloonist/Yachtsman Extraordinaire, for the loan of his Harley-Davidson FLH, back in London after having been across Europe west to east, as in Russia, and south to north, up past the Arctic Circle. A reliable piece and wonderful at starting conversations and comfortable and anyway I love to fly the flag. Sure, said Malcolm, provided you don’t drop it as I am riding to Scotland the week after TT Week.

So it was that I got out of bed in London, saw not a cloud in the sky and rode west. England is a usefully sized country. I chuffed along country roads, visited Woodhenge (dress rehearsal for Stonehenge but that’s another story) had lunch in a pub, got wet while struggling into my rainsuit in time for the shower to cease instantly I was protected from it, visited a muffler shop for a bolt missing from the front cylinder, had tea with a Vincent owner also on his way to the TT and got to Liverpool just before dark. The hotel was ever so nice about letting me park at the front door.

In the morning into the stream of motorcycles and down to the docks. One of the non-sporting reasons TT Week still lives is simply tourism. They schedule the races at the beginning and end of the tourist season, stretching things and adding to the visitor total. And although the racing is free—no way could they fence off all 37 miles of public road—one must pay to get there and stay there and get back. It’s 70 miles from the coast of England and nearly as far from Ireland and Scotland. Thus, the boat ride, one bike and one rider, round trip, cost $95 in cash.

All we cyclists got in line and had our tanks nearly drained, for safety they said although there were mutterings about just where does the gas go, anyway? Then we all did a sardine number into the hold of the steamer, where crewmen handed out ropes and we lashed our machines to each other. Then we spent four hours drinking tea and turning pale and came wobbling down the ramp into Douglas, largest town on the land.

Motorcycles! Wow! Back in the Victorian tourist days the seaside of Douglas was covered with boarding houses and that’s where many thousands of fans stay. The police have arranged for motorcycle parking, at the curb, on the sidewalk, all over the place. Here’s a Bimota with Suzuki power, there’s a Triumph TR5, two Velocettes, a Honda GL with CR1100 fairing, a Nimbus Four with sidecar, a Sportster with German plates, a variety the average motoring museum couldn’t match, all being ridden.

Time for a lap, which nearly overcame the power to believe one’s eyes. First, this really is racing on roads. Normal roads. The start-finish is on the high street in Douglas. Picture a mining town, crowded and hilly. The course drops down Bray Hill, a real hill and slams through a kink, through a residential neighborhood, around a traffic circle, all with curbs and gutters and walls and utility poles. Out of town and along what looks like a New England country road, then into a winding section, the sort of terrain you find in Idaho and New Hampshire; trees and haystacks and driveways, all festooned with racing banners and shielded, in hopes anyway, by straw bales. Your traffic engineers and mine would post these places 35 to 55 mph. Before the week is out the lap record will be an average of 1 1 5.

1 loved it. Not the speed, an FFH is not that sort of vehicle, but one could get some impression and there before me were all the signs of legend. Bray Hill. Quarter Bridge. Ballacraine, Ballaugh Bridge, Sulby Straight (which isn’t at all, being more like a series of gentle bends). Hairpin, Waterworks, Gooseneck, Windy Corner, Keppel Gate, Kate’s Cottage, tearing down through Creg-ny-Baa, into Brandish straight where the big jobs hit 175, banked around Signpost into the kink known as Governor’s Bridge, where I thought we’d made a mistake and gone into somebody’s driveway, and across the finish line. Forty minutes if you hustle, less than 20 if you’re Joey Dunlop, Mick Grant or Graeme Crosby.

Escalating from there, TT Week is like Daytona, Assen and Suzuka in that every fan who can attend, does. But IoM is pub-

lic roads. Right, open to the public when not closed by act of the House of Keys.

And there are no speed limits outside the towns.

Got it right first time. While we normal chaps are briskly riding around, taking note and admiring the view ZzzrrrrWhaAAA!, there goes the Bimota-Suzuki with a Trident in pursuit, paced by two Desmo Dukes, all this when you’re moving into the center of the road to pass the white-haired couple in the Nimbus combination.

More of this to come.

TT racing has evolved into its own formula. This is a week-long event, two weeks if you count practice. There is a series of races, with modern rules using names dating back to 1907. Because I’d read about this and never had it explained, I took some trouble to obtain a translation from the natives.

First race in TT Week is the TT, short for Tourist Trophy but nothing like our TT racing. Instead it’s Formula One, like our Superbikes except that we use stock frames (or we’re supposed to and don’t) and radical carburetors and the English use racing frames and stock carbs, sort of. Daytona four-strokes, in sum, with a 1000cc limit or you can use a 500 two-stroke if you wish. Factory teams here, from Honda, Suzuki and Kawasaki and the big four-strokes have the edge.

Then a two-part sidecar race, to FIM rules except that the rough roads would fatigue a GP combination so mostly it’s British clubmen.

The Senior Race is freeform, 500cc limit so that’s where the Grand Prix machines appear, sometimes from the factories but mostly privateers. The Junior race is likewise except that it’s FIM-style 250s, again a GP class.

Clubmen dominate the Formula Two and Formula Three world championship, which is like our Production or Modified Production: mass-produced engine, with mods and any frame you please. The smaller formulae are the home of tuned Aermacchis and Ducatis and a screaming horde of water-cooled Yamaha FC250s and 350s.

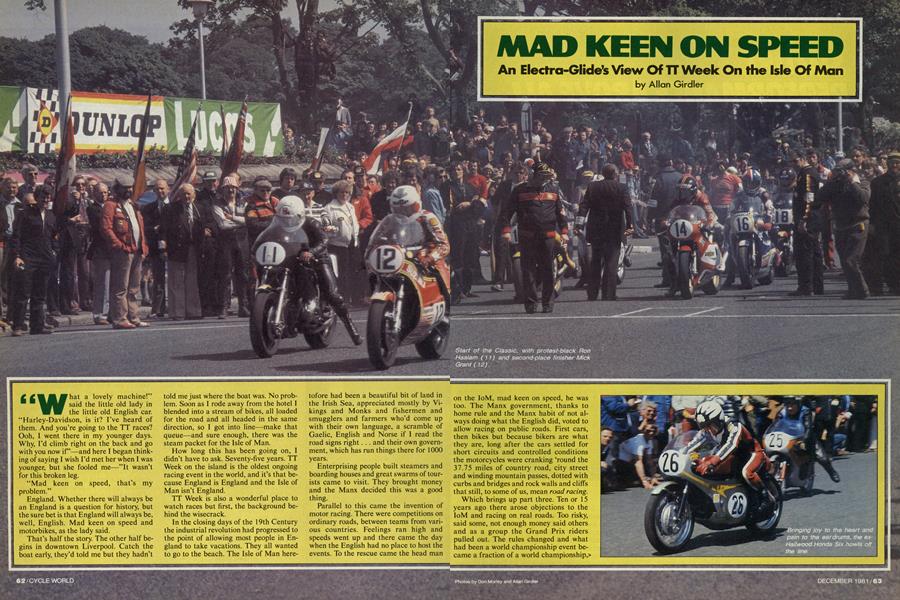

Final and Biggie of the week is the Classic, sort of a run-what-you-already-run class. It’s open to the Formula Ones, and the GP 500s plus anything else you have in the back of the shed, the only restriction being no more than 1300cc displacement. There weren’t any stroker Harleys or super big bore Ducatis, sad to say. Instead, it’s a repeat—underline that—of the TT race.

On top of the machines, so to speak, are the riders. Roberts and Sheene and Mamola et al don’t race here any more. But heroes aren’t born, they’re created. If we didn’t have Roberts and Hannah and Springsteen, we’d have to appoint other guys to take their places on the pedestal.

There’s extra reason for that at the Isle

of Man. TT Week has been The Race for generations, then here come these outsiders who don’t want to ride in it, who don’t care. The Italians and the Americans and even some English and worse, they were and are good racers and brave men, so you can’t even call them names. Instead, TT racing has evolved its own stars, usually riders who have displayed world-caliber talent, like Mick Grant, but who lack Grand Prix rides for one reason or another. At this peak are Grant, Ron Haslam, Alex George and Joey Dunlop, with nearly equal rank going to Crosby and Jon Ekerold, who both do Grands Prix and ride on the island, albeit Ekerold was paid lots of money and didn’t look all that good. Then there are a whole bunch of British club racers, followed by sportsmen. The British have a sporting tradition and the TT has always lured guys who simply wanted to be there. If you finish within a certain percentage of the winner’s time, you get a replica of the winner’s trophy and mighty good it looks on the mantlepiece.

Which means there may be 100 or more entrants per race. On a two-lane road? To take care of that the riders start by the clock, two men every 10 seconds and it’s all computed during the six laps. If, say, the first man out is eight seconds ahead of the second man, he’s behind by two seconds and so forth. (This became critical, as we’ll see.)

TT Week has to be heaven for spectators. There are grandstands at the startfinish line, but don’t bother. Because this is a road course and they want to have a full week and need to allow for weather, the race may begin at 11 a.m. The road is closed at 10, so at 9 all the fans ride along the course until they come to a vantage point they fancy. You park your bike on a side road, and find a place on the wall or the hillside. Manx Radio serves as the announcer so you watch a close-up of the action right in front of you while the radio gives reports of all the standings and times and drama everywhere else.

My host Cathcart races old bikes and has raced in the TT and the formula classes, so he picked the sites. For the TT proper we went to Glen Helen, a corner named Black Dub although nobody seemed to know why.

Amazing. We motored into the country, along a winding lane bordering a trout stream. We parked behind a gas station and hiked past a cafe to a stone wall. To our left, the winding, tree-shaded road. To our right, a kinked left and cambered right across a bridge with stone walls on both sides.

News from the radio. Crosby wasn’t in his place in line. He was in the back, helmet off. Seems his Suzuki’s front tire began to go soft as he lined up near the front. He’s been told he could swap tires and start last, with no penalty. But as the first rows fired up, we were told Crosby> would have to make up the six minutes, that is, his times would start with the row he was supposed to be in while he himself would be flagged away six minutes after that.

The race was on. We heard the reports from the corners and watched the map . . .

First comes the noise, an echoing shriek then Bang! out of the trees came Joey Dunlop on the red Honda four-stroke, crouched on the bars, concentration so intense it crackled out of his eyes, neat sharp motions as he swung wide at the gas station, took a late apex and came into the kink just right to slam the bike up and over, across the bridge and gone.

A few words about Dunlop. He’s an underdog, an Irish rider trained in their rough-and-tumble club events. He came to the IoM last year on a budget so tight he hitched a ride to the island on a friend's fishing boat. He brought a privateer Yamaha TZ750. And he won the Classic. I heard an interview on the radio. Never met the man, never seen him ride but from the sound of his voice, I decided to root for Dunlop. He sounded like one of our guys. No, not the accent, that was so Irish I could hardly catch one word of three. But hearing him talk about racing was hearing the spirit of American club events.

Dunlop’s win got him a ride on the Honda team. More odd stuff. Dunlop and Haslam and Alex George are heroes. Team Honda is not. If I interpreted the natives right, Honda is considered poor sports, always trying to buy victory. And Crosby, who I thought was entertaining and open and funny, if sometimes too frank about his feelings concerning other riders and officiais, is not popular.

There was a stream of riders and something less than six minutes after Dunlop whammo!, Crosby on the Suzuki, high wide and handsome, using all the road, the steering lock and the throttle, slashing between two hapless mid-packers and away, all loose and sideways.

We sat and watched and listened. Dunlop was pulled in for a tire change as rain threatened, and Haslam had the lead while Crosby chopped away at that six minute handicap and Dunlop whittled away at the minute he’d lost. At the end of the six laps it was Haslam, Dunlop and Crosby and they waved the flag and poured the champagne.

Suzuki filed a protest. Not until the next day did the jury rule that Crosby had been properly advised to go to the back of the line without penalty. His times were computed from when he crossed the starting line, Crosby was the winner with Haslam second and Dunlop third. The crowd booed Crosby at the belated prize giving, Honda threatened to pull out of TT Week altogether. I don’t know what they did about the champagne.

Sidecars next, more an exhibition than race. Jock Taylor is Britain’s only world champion and the other GP chairs didn’t show. Taylor and passenger Bengt Johansson, a Swede, whipped around at record speed, waving at the crowd.

For Sunday there was a break in the uh, official racing.

Get ready. Not only do they have these races and allow fans to ride around the circuit, they encourage it. On the Sunday between races the back portions are made one way. Down the straight and over the mountain with no oncoming trafile.

They call it Mad Sunday.

They call it right.

There were Ducatis and Suzukis and CBXs and Laverdas and all like that, plus the occasional Norvin (Vincent Twin in Norton frame) and Triton (Triumph Twin in Norton frame) and flocks of homebuilts, many of which showed work and talent. Not really a race, in the sense of having to come in first, as along with the scratchers came full-dress BMWs, a virtual parade of Harleys and so many Velocettes we stopped looking except for the

really good ones. All going the same direction, some faster than others. Maybe the rain and fog slowed things down, but there were no incidents.

For the Senior, the 500 GP, we went to Gooseneck, a tight turn as you'd guess and again, there’s a network of roads and lanes leading to the course. The popular places even have hot dogs and tea and you can park nearby and hoof it to a vantage point. Rain again and fog, so thick they couldn’t use the emergency helicopters and stopped the race after two laps. Also after the parking lot turned into mud and all the cars and bikes were stuck. Except for one chap on a Rickman Triumph. He putted up the hill and down the hill and up again and down again while all about him people slid into ditches or dug themselves deeper. He was laughing a lot.

Tor the Junior, Ballaugh Bridge. That’s the one with the hump, where all the pictures of leaping bikes are taken.

It’s pronounced with an “r”, by the way, as in “Don’t mike me larf, mite.’’ You can still hear Manx spoken in the street and

some of the names retain their original flavor. Our cottage was in the village of Onchan, which I pronounced to rhyme with Charley Chan and they all looked puzzled. The proper way is Onkin, as in “ ‘E ain’t af ‘onkin’.’’

This works both ways, of course. We had lunch in the Ballaugh parish hall, where the ladies of the parish, all right out of an Agatha Christie novel, do well for the church by doing good cooking for the fans. “You must be from America,’’ said one after I'd ordered. “You Americans call everybody ‘m’am.’’

All I could think of to say was “Yes, m’am.''

The bridge is a fine test of talent. Some riders rolled off and coasted over, some gassed it and got the front wheel up, just like motocross, and many came down “kablunk’’ on the front wheel, as if they’d been caught by surprise six laps in a row.

There’s more to the Isle of Man than motorcycles. Not being all that interested in the smaller formulas the AMA’s Garry Winn and I took time out to visit King> Orry’s grave, a prehistoric burial site, and toured the Manx Museum and rode on the tiny steam train and bought sweaters, just like tourists anyplace.

Nor are all the motorcycles racing. There was a vintage rally and various onemake club functions, even a Harley one although I didn’t know until I’d already been elsewhere at the time. By this late in the week we were having a daily collection of neat machines, with voting as to which of the best we’d like best, but because they varied so—Wednesday’s bag included a Panther Sloper, a Brough Superior with chair and a Seeley-Triumph—we never actually had a winner.

Came Friday, the big race, the Classic. We went to the start/finish line. A mistake, on hindsight. Somehow when you’re out on the course, watching the racers flash past while getting the news from headquarters works. But when the racers leave you there and go off and perform someplace else, it takes away.

But there was drama in the pits. Team Honda’s reaction to the reversal of the TT finish was to Not Officially Appear. They painted the machines black, the riders wore black leathers and the mechanics had black coveralls. “We hope in this way to express our disgust at events,” team manger Gerald Davison said, “without in-

terfering with the racing.”

No worry there. Dunlop’s second lap was the fastest in IoM history, 19 min. 37 sec., 1 15.4 mph. On his third lap Dunlop ran out of gas. He pushed nearly a mile, made it to the pits and dropped out down the road, the engine ruined. Crosby and

the Suzuki won that one, too, followed by Mick Grant and his Suzuki and lone Team Honda survivor Alex George.

The real reason for being at start/finish, though, was the old bikes. Confusion again, in that what we loosely refer to as vintage in the U.S. means really oldies in the U.K., so their just-outmoded racing machines are classics. So they take part in the T.T. Classic laps of honor.

Impossible to describe or list. There were fully 100 true classics, everything good ever built. Riders? Standing next to that MV is Geoff Duke. And there with the 1939 KTT Velocette is Stanley Woods, age 78, who first rode here in 1922. Eleven wins, in all and he still looks fast. What will we ride like when we’re 78?

Double high. They were bump-starting the older Singles, which sound like racers despite those funny saddles and rigid frames, when cutting through the boom came the damnedest Banshee wail any of us is likely to hear.

Honda’s fantastic Six, as ridden by

Hailwood here. They had to start it on rollers and keep it revving 5 thou or so while it warmed up. Then Tommy Robb came off the line like a missile and the sound was enough to literally turn your head. Unbearable and yet I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.

The second Hailwood machine was the Ducati on which Mike made his comeback in 1978, ridden this time by American journalist Dale Boiler, who was editor of Motorcyclist and ran the first story about Hailwood’s plan. The Ducati’s tuner thought it would be appropriate if Dale rode the bike.

Two laps and Boiler was nearly speechless. Because he’d ridden racing Ducatis before, for instance Cook Neilson’s Daytona Superbike winner, he thought he knew what he was in for. No, he said, everything is so compressed, it all comes rushing at you so fast, that practice laps on a road bike are a waste of time. What fun, in other words.

That also begins to sum up TT Week. The Isle of Man is not at all like other racing. It’s unique. Dangerous and demanding and one cannot fault racers who won’t ride there. On other tracks, modern short circuits, the trick is to know when to go slowly. At IoM, the trick is knowing when you can go fast, which of the countless and confusing corners exits onto a straight, and which kinks back the other way. The penalty for not knowing is severe

and the men who do go quickly here are a breed and a talent apart.

The trip contained one unpleasant experience, which I could have avoided if I’d appreciated the character of the island in time.

We were driving to dinner one night and Cathcart said get ready. We’re coming to a bridge controlled by the Little People. If we don’t pay homage, they will get even. So as we drove across, we all in foolishfaced unison chorused “Good Evening, Fairies” and felt as ridiculous as that looks on paper. Ditto the return trip, and then I forgot all about it.

After the races we got back on the steamer and rocked back to England. Docked at 2 a.m. and rode to the hotel. In the rain. I parked the Harley in front of the door and went inside to be sure our reservations were good. They were, so I went back to get my gear . . .

My helmet was gone. My lovely new red Bell Star. Figure the odds for a thief to be walking past the hotel at 2:15 in the morning, just in time to see my helmet unguarded and leg off down the street before I got back.

Odd, nothing. I was standing, staring at where my helmet had been, muttering that old lament, Why me. Lord? when I realized that I’d ridden to the vintage rally and back, on that road, across that bridge. I had forgotten the Little People. They hadn’t forgotten me. g

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

December 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1981 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

December 1981 -

Features

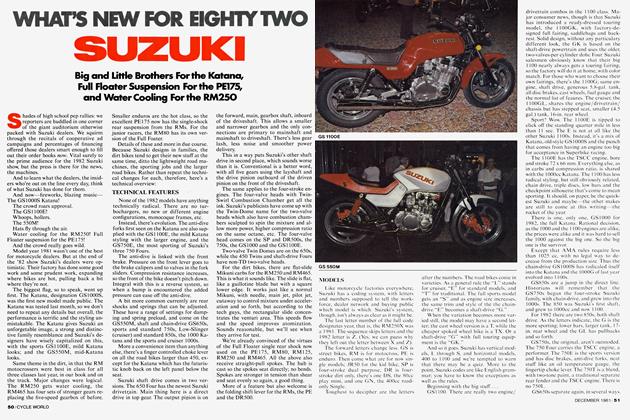

FeaturesWhat's New For Eighty Two Suzuki

December 1981 -

Departments

DepartmentsBook Reviews

December 1981 By Henry N. Manney III -

Features

FeaturesA Guide To Orphan's Homes

December 1981 By Dee Winegardner