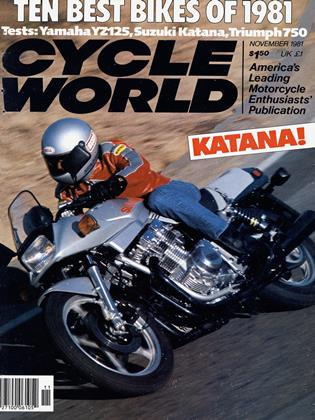

SUZUKI GS1000S KATANA

CYCLE WORLD TEST

“Let Us Leave Pretty Women To Men Of No Imagination” ...Marcel Proust

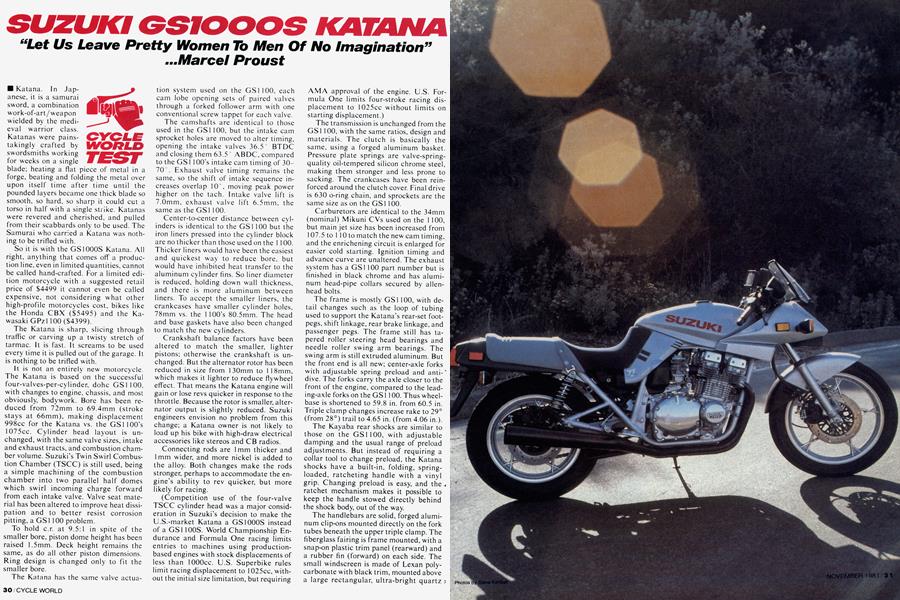

Katana. In Japanese, it is a samurai sword, a combination work-of-art/weapon wielded by the medieval warrior class. Katanas were painstakingly crafted by swordsmiths working for weeks on a single

blade; heating a flat piece of metal in a forge, beating and folding the metal over upon itself time after time until the pounded layers became one thick blade so smooth, so hard, so sharp it could cut a torso in half with a single strike. Katanas were revered and cherished, and pulled from their scabbards only to be used. The Samurai who carried a Katana was nothing to be trifled with.

So it is with the GS1000S Katana. All right, anything that comes off a production line, even in limited quantities, cannot be called hand-crafted. For a limited edition motorcycle with a suggested retail price of $4499 it cannot even be called expensive, not considering what other high-profile motorcycles cost, bikes like the Honda CBX ($5495) and the Kawasaki GPzl 100 ($4399).

The Katana is sharp, slicing through traffic or carving up a twisty stretch of tarmac. It is fast. It screams to be used every time it is pulled out of the garage. It is nothing to be trifled with.

It is not an entirely new motorcycle. The Katana is based on the successful four-valves-per-cylinder, dohc GSl 100, with changes to engine, chassis, and most obviously, bodywork. Bore has been reduced from 72mm to 69.4mm (stroke stays at 66mm), making displacement 998cc for the Katana vs. the GSl 100’s 1075cc. Cylinder head layout is unchanged, with the same valve sizes, intake and exhaust tracts, and combustion chamber volume. Suzuki’s Twin Swirl Combustion Chamber (TSCC) is still used, being a simple machining of the combustion chamber into two parallel half domes which swirl incoming charge forward from each intake valve. Valve seat material has been altered to improve heat dissipation and to better resist corrosion pitting, a GSl 100 problem.

To hold c.r. at 9.5:1 in spite of the smaller bore, piston dome height has been raised 1.5mm. Deck height remains the same, as do all other piston dimensions. Ring design is changed only to fit the smaller bore.

The Katana has the same valve actuation system used on the GSl 100, each cam lobe opening sets of paired valves through a forked follower arm with one conventional screw tappet for each valve.

The camshafts are identical to those used in the GSl 100, but the intake cam sprocket holes are moved to alter timing, opening the intake valves 36.5° BTDC and closing them 63.5° ABDC, compared to the GSl 100’s intake cam timing of 3070 . Exhaust valve timing remains the same, so the shift of intake sequence increases overlap 10°, moving peak power higher on the tach. Intake valve lift is 7.0mm, exhaust valve lift 6.5mm, the same as the GS 1 100.

Center-to-center distance between cylinders is identical to the GSl 100 but the iron liners pressed into the cylinder block are no thicker than those used on the 1 100. Thicker liners would have been the easiest and quickest way to reduce bore, but would have inhibited heat transfer to the aluminum cylinder fins. So liner diameter is reduced, holding down wall thickness, and there is more aluminum between liners. To accept the smaller liners, the crankcases have smaller cylinder holes, 78mm vs. the 1 100’s 80.5mm. The head and base gaskets have also been changed to match the new' cylinders.

Crankshaft balance factors have been altered to match the smaller, lighter pistons; otherwise the crankshaft is unchanged. But the alternator rotor has been reduced in size from 130mm to 1 18mm, which makes it lighter to reduce flywheel effect. That means the Katana engine will gain or lose revs quicker in response to the throttle. Because the rotor is smaller, alternator output is slightly reduced. Suzuki engineers envision no problem from this change; a Katana owner is not likely to load up his bike with high-draw electrical accessories like stereos and CB radios.

Connecting rods are 1mm thicker and 1 mm wider, and more nickel is added to the alloy. Both changes make the rods stronger, perhaps to accommodate the engine's ability to rev quicker, but more likely for racing.

(Competition use of the four-valve TSCC cylinder head was a major consideration in Suzuki’s decision to make the U.S.-market Katana a GS1000S instead of a GSl 100S. World Championship Endurance and Formula One racing limits entries to machines using productionbased engines with stock displacements of less than lOOOcc. U.S. Superbike rules limit racing displacement to 1025cc, without the initial size limitation, but requiring AMA approval of the engine. U.S. Formula One limits four-stroke racing displacement to 1025cc without limits on starting displacement.)

The transmission is unchanged from the GSl 100, with the same ratios, design and materials. The clutch is basically the same, using a forged aluminum basket. Pressure plate springs are valve-springquality oil-tempered silicon chrome steel, making them stronger and less prone to sacking. The crankcases have been reinforced around the clutch cover. Final drive is 630 o-ring chain, and sprockets are the same size as on the GSl 100.

Carburetors are identical to the 34mm (nominal) Mikuni CVs used on the 1 100, but main jet size has been increased from 1 07.5 to 1 10 to match the new cam timing, and the enrichening circuit is enlarged for easier cold starting. Ignition timing and advance curve are unaltered. The exhaust system has a GSl 100 part number but is finished in black chrome and has aluminum head-pipe collars secured by alienhead bolts.

The frame is mostly GSl 100, with detail changes such as the loop of tubing used to support the Katana’s rear-set footpegs, shift linkage, rear brake linkage, and passenger pegs. The frame still has tapered roller steering head bearings and needle roller swing arm bearings. The swing arm is still extruded aluminum. But the front end is all new; center-axle forks with adjustable spring preload and anti-1 dive. The forks carry the axle closer to the front of the engine, compared to the leading-axle forks on the GS l 100. Thus wheelbase is shortened to 59.8 in. from 60.5 in. Triple clamp changes increase rake to 29° (from 28°) trail to 4.65 in. (from 4.06 in.).

The Kayaba rear shocks are similar to those on the GS1100, with adjustable damping and the usual range of preload adjustments. But instead of requiring a collar tool to change preload, the Katana shocks have a built-in, folding, springloaded, ratcheting handle with a vinyl grip. Changing preload is easy, and the ^ ratchet mechanism makes it possible to keep the handle stowed directly behind the shock body, out of the way.

The handlebars are solid, forged aluminum clip-ons mounted directly on the fork tubes beneath the upper triple clamp. The fiberglass fairing is frame mounted, with a snap-on plastic trim panel (rearward) and a rubber fin (forward) on each side. The small windscreen is made of Lexan polycarbonate with black trim, mounted above a large rectangular, ultra-bright quartz; halogen headlight. The 5.8 gal. sculptured gas tank is steel, while the contoured seat has a light plastic pan and two-tone (blue and gray) synthetic suede (vinyl) covering. The seat is low at 30.5 in., but not as low as the high-backed tank makes it appear. The tail section is plastic, as are the fenders. The front fender hides a stampedsteel fork brace.

Side covers running from the rear of the tank along the bottom of the seat are plastic, ending abruptly on each side to let some mechanical and electrical parts show. The choke controlan unusual large, rotating knob, is recessed into the left side panel. Below the choke control are two accessory on/off switches, and the covered fuse box directly rearward of the panel includes a pair of screw terminals for accessories.

Instruments are carried in a neat pod above the upper triple clamp, idiot lights on the bottom, 85-mph speedometer on the left and rotating from bottom right to upper left, electronic tach on the right and rotating from upper left to bottom right. The ignition switch, located beneath the instruments, does not include a steering lock. Instead, a stronger type Germanmade, anti-theft lock is built into the steering head on the left side.

Control pods—including self-canceling turn signals—are conventional enough, but the front master cylinder is shaped to fit the clip-on bar while keeping the fluid reservoir mostly horizontal. The mirrors are masterpieces, actually providing excellent rearward vision, adjustable to accommodate any riding position from completely tucked-in to sitting upright.

To those who value function, the GS1000S follows the maxim “beauty is as beauty does.” It takes some getting used to, this futuristically-styled, limited production monster bike from Suzuki. But high-speed riding sessions across desert roads, around a twisty race track and down the uncompromising straightaway of the dragstrip wear down reservations and make the Katana look better and better.

It is the quickest and fastest lOOOcc production motorcycle we’ve tested, turning the quarter-mile in 11.32 sec. with a terminal speed of 120 mph. It stops in a shorter distance from 60 mph—122 ft.— than any larger-than-500cc motorcycle we’ve tried. And, delivering 54.2 mpg on the Cycle World mileage loop, the GS1000S gets better mileage than anything in its class.

When riding tucked in, the rider is so completely behind the fairing/windscreen that frontal area is reduced, a fact reflected in the Katana’s record-setting halfmile speed of 140 mph, a full five mph faster than the GS1100 and GPzl 100.

The accumulation of all those parts and changes weighs less than one might expect, 543.6 lb. with half a tank of gas. That’s less than the GSl 100 (556 lb.), the GPzl 100 (551 lb.) and the CBX (662 lb.), and only slightly more than the lightest Four in the class, the standard model KZ 1000J (535 lb.).

For all its looks and style and trick parts, the Katana is not what one would call an ideal in-town mount. It wasn’t as bad as some riders feared from experiences with clip-on equipped bikes. Underneath it all, the Katana remains a normal motorcycle, which means it idles and the clutch always works and it’s easy to find neutral. Seating position for low-speed work is the best we can remember for a bike with rearsets and clip-ons, but at low speeds the rider still must support his upper body weight in the lean-forward riding position the bar/ seat/pegs relationship was designed for. Some riders had to remember to consciously pull their feet up and clear their boot heels off the pegs before rolling to a stop, lest they be caught with feet up and no momentum. There’s something about the angle of the clip-ons that puts the control switches, for example the horn button, not quite where expected and in traffic that takes some attention at first.

The CV carburetors are terribly touchy at low engine speeds. Coupled with the reduced alternator rotor weight, this makes the bike lurch forward at the tiniest change in twist grip position. When threading through a traffic jam, holding steady throttle and/or road speed is difficult.

Contributing is the harshest, stiffest ride this side of a hardtail. Hit a bump— say, a frost heave in the roadway—at 35 mph and the rear end jumps upward and the rider’s right hand moves a tiny bit and the bike lurches in response in that nonprogressive manner common to CV carbs. In very slow turns and in driveway maneuvers, the Katana feels top heavy. One doesn’t want to lean the wrong way when traversing a sloped drive.

In spite of the reduced flywheel effect the Katana will very happily torque away from a stop at 1 500-2000 rpm. But while close to the GS 1 100 version in peak power, the Katana doesn’t have the same grunt at low rpm, instead making its best power over 5000 rpm. Which makes it a little harder to launch at the drags than the GSl 100.

And it vibrates. At an indicated 55-60 mph on the highway, the Katana buzzes the bars enough to tingle hands through heavy gloves and blur the rearview mirrors. Step up the pace to 70 mph and the buzzing diminishes in the bars. At 80 mph the bars are better still, but the buzz intensifies in the footpegs. An hour’s fast riding can leave the outside edge of the rider’s soles tingling. An hour’s ride at legal or near-legal speeds will leave feet untouched but hands tingling.

And kidneys and other internals feeling like a bowlful of jelly.

Remember that stiff ride? Few motorcycles are as bad on concrete highway expansion joints as the Katana ridden solo by a 1401 50 lb. pilot. Even at minimum fork and shock spring preload settings the Katana seems to transmit every little jolt directly to the rider’s insides. One man took to wearing his off-road kidney belt and reported that it made the ride bearable. The closer to the legal speed limit, the worse the Katana was over small repetitive bumps, especially those awful concrete seams.

Even on relatively smooth asphalt highways, hitting the occasional significant bump at 50-55 mph would launch the rear end of the bike off the ground, air appearing between the rider’s butt and the seat.

The answer is to ride fast. Very fast. The faster, the better. At 80 mph on open country roads, the air blast reaching the upright rider around the small windshield balances nicely against the weight of the rider’s body leaning on the bars. The effect is to relieve the pressure on the arms and make the position feel neutral. The bike is most comfortable well into the powerband (80 mph equals 5100 rpm) and as smooth as it’s going to get. At that speed the suspension, on the minimum preload, is only marginally too stiff, and the bike does better over the bumps. Complaints about carb snatchiness disappear. The pegs and bars feel right, the seat is comfortable for an hour or so of blasting past all comers. The Katana is in its element.

Turn up the throttle yet another notch, take the Katana to the race track, and the situation changes again. The suspension is radically oversprung. Pitch the bike into a w ide-open, top-gear sweeping turn and the first bump bounces the rear wheel off the pavement and sets up an intimidating wobble. On smooth, flat corners the Katana gets away with too much spring. But it cannot handle the bumps.

We can understand why. Suzuki’s test track near Hamamatsu, Japan, has several top-gear sweeping turns, but they are nothing like the bumpy test of man and machine that makes up Willow Springs Raceway’s notorious Turn Eight. The problem has shown up before, when prototype racebikes tested at Suzuki's track arrive in the U.S. for testing at Willow, or even at Suzuka Circuit in Japan. Other manufacturers have the same problem . . . their test tracks are too good, the surfaces too smooth, too perfect to determine best real-world performance.

What the Katana needs is new shocks with softer springs and maybe less compression damping as well. And softer fork springs. Bolting on a set of aftermarket shocks and experimenting with available springs would take care of the rear end. Locating proper-length, softer springs for the forks may be tougher, but just as important. Then again, springs from center-axle forks used on another Suzuki model might be applicable.

Ignore the springing problem, slow a bit in the bumpy turns and concentrate on what the Katana does elsewhere. It screams down the straightaway, flies through smoother turns, cuts through leftright transitions. The rider has to work to ride the Katana fast, wrestling the clipons, but the perspective the bike gives is different from that of a normal street bike.

It is in feel, in performance, in looks, the closest thing to a Formula One racebike any body can buy off the showroom floor.

The Katana’s cornering is limited in slower turns by the center and side stands, the centerstand feet dragging on both sides and the sidestand tip touching down on the left. The tires work well enough at the kind of speeds that can be risked with the too-stiff suspension, although the combination of stiff fork springs, turning and braking hard over bumps sets up a frontend chatter close to that plaguing slicktired Formula One racebikes, the horizon tilting and bobbing as the rider struggles to get into the turn deep and get out the other side.

The brakes are excellent, with good feel. The anti-dive feature is not drastically noticeable when riding normally, except that the front end does not collapse with full braking and then hop over bumps. Instead, especially in stops to zero mph, the forks retain some ability to deal with road irregularities when the brakes are on. The result is better traction and control under braking, which shows in the Katana’s outstanding stopping distances of 1 22 ft. from 60 mph and 29 ft. from 30 mph.

The anti-dive works the same way the system used on Suzuki GP bikes (and the Yamaha Seca 750) works. When the brakes are applied, fluid pressure closes a valve in an externally-routed damping oil passageway, restricting the flow of damping oil and slowing fork compression. The valve is spring-loaded, so if a sharp bump is hit, the extra pressure blows the valve off its seat and allows the forks to compress a bit to handle the bump.

We seem to be image-deep in the Age of the Statement. This goes beyond Specials and Grand Prix replicas. Honda introduced the CX500 Turbo in part because the company wants everybody to know motorcycles can be elegant . . . and as complex as the average space shot. Yamaha is double-timing it in style and electronics, flashing lights and display panels and bold color and line. Kawasaki is flexing muscles and trimming away excess weight.

Suzuki has not always been good at image. Some of the better Suzukis of the past, i.e. the GT750, were great bikes that looked clumsier than they were. Parked in our garage is a GS1100 and the more we ride it, the better we like it. The performance we knew from the test but the other virtues; the lightness and precision of the controls, the logic of the switches, etc., are things that only are appreciated after months of use. Good design, in short, which increases customer satisfaction.

That isn’t the same thing as consumer awareness, so last year Suzuki’s designers worked with consultant Hans Muth and came up with the arresting collection of shapes known as the Katana.

The shapes add up to more than a collection. The fairing is a narrow wedge, the windscreen is separate and more upright than usual. The front fender is two-tone, silver and black but the black panel is nearly invisible, obviously by intent. The tank is large and peaks at the back. The seat is a valley, with the dark panel accentuating the dip and the aft panel is gray. The color is so close to that of the bodywork that the Katana’s ability to carry a passenger is disguised.

Parked, all this doesn’t quite add up. The eye races madly across divergent lines. There is no unity. One bike nut said it seemed almost a shame, somehow, that such a machine had an ordinary engine in it. The normal Four brought the design back down to earth, so to speak.

In motion, the Katana changes. The shapes flow together. The rider fills the valley behind the tank and blends into the machine. The creases on the sides of the fairing become intense speed lines. Banked into a turn the Katana is one shape, moving fast and aggressively, a silver shark . . . and we are looking at a motorcycle designed to be seen with rider, in motion.

That may be the most radical idea of all.

Nor will Suzuki’s statement stop here. In Europe there is already a selection of Suzukis with the Katana theme. The 650s and 750s don’t go this far. The tanks are more round and the fairing is absent, but the impact is there and Suzuki has a look at least as distinctive as Honda’s beltline ar the Kawasaki ducktail fender.

What the Katana is—finally, completely, simply—is a no-compromise sport bike, with flaws. The flaws are centered around the too-stiff suspension. Beyond that, the Kantana is not rationalized or toned down to appeal to a larger group of buyers. It is what it is, does what it does, looks like it looks, and makes no apologies.

The Katana cries out to be ridden, and ridden hard, to be used every time it is pulled from the garage. It attracts strong emotional responses. That in itself makes this radical machine a remarkable Japanese motorcycle. S

SUZUKI

GS1000S KATANA

SPECIFICATIONS

$4499

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1981 -

Departments

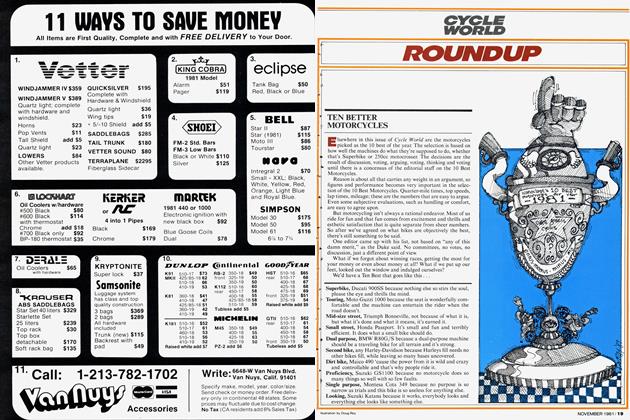

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1981 -

Laguna Seca

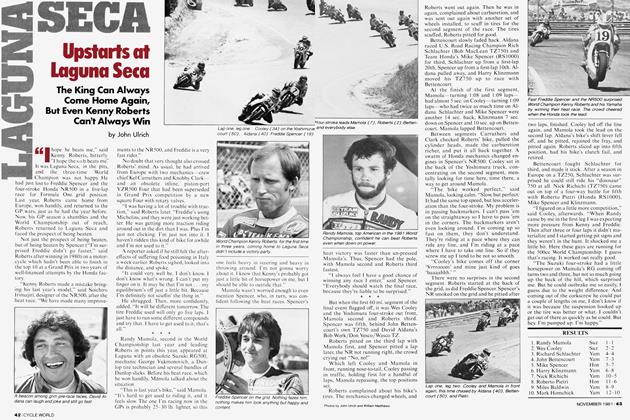

Laguna SecaUpstarts At Laguna Seca

November 1981 By John Ulrich -

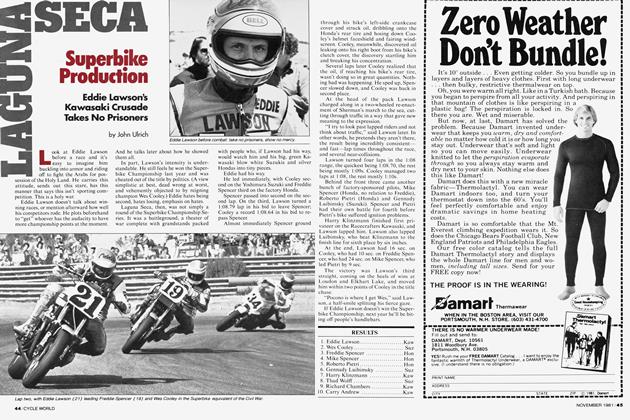

Superbike Production

November 1981 By John Ulrich -

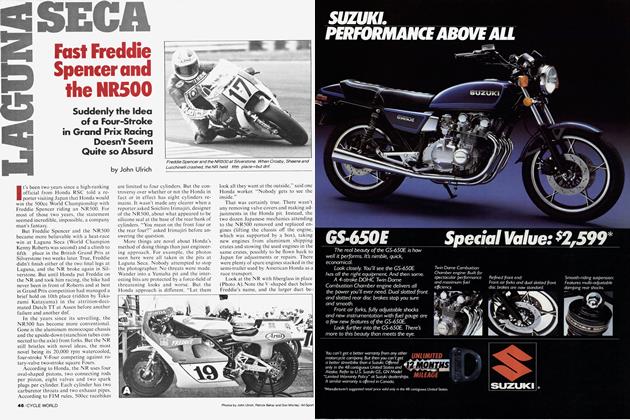

Fast Freddie Spencer And the Nr500

November 1981 By John Ulrich