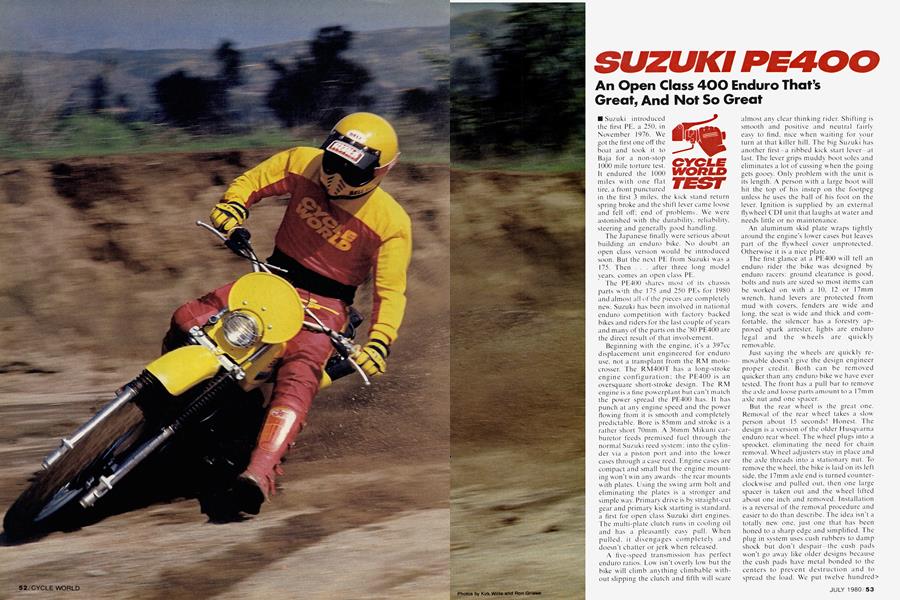

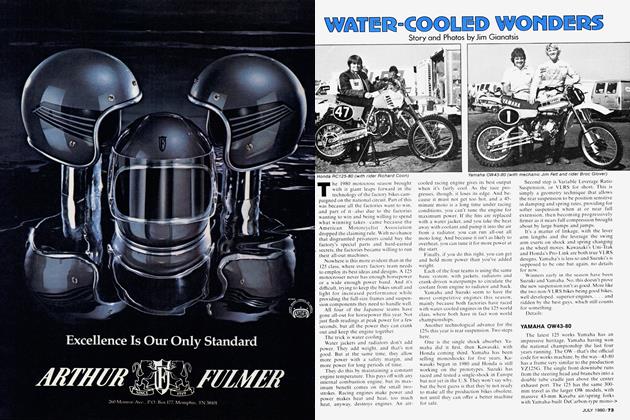

SUZUKI PE400

CYCLE WORLD TEST

An Open Class 400 Enduro That's Great, And Not So Great

Suzuki introduced the first PE, a 250, in November 1976. We got the first one off the boat and took it to Baja for a non-stop 1000 mile torture test. It endured the 1000 miles with one flat tire, a front punctured in the first 3 miles, the kick stand return spring broke and the shift lever came loose and fell off; end of problems. We were astonished with the durability, reliability, steering and generally good handling.

The Japanese finally were serious about building an enduro bike. No doubt an open class version would be introduced soon. But the next PE from Suzuki was a 175. Then . . . after three long model vears, comes an open class PE.

The PE400 shares most of its chassis parts wfih the 175 and 250 PEs for 1980 and almost all of the pieces are completely new. Suzuki has been involved in national enduro competition with factory backed bikes and riders for the last couple of years and many of the parts on the ’80 PE4Ö0 are the direct result ofthat involvement.

Beginning with the engine, it’s a 397cc displacement unit engineered for enduro use. not a transplant from the RM motocrosser. The RM400T has a long-stroke engine configuration; the PE400 is an oversquare short-stroke design. The RM engine is a fine powerplant but can’t match the power spread the PE400 has. It has punch at any engine speed and the power flowing from it is smooth and completely predictable. Bore is 85mm and stroke is a rather short 70mm. A 36mm Mikuni carburetor feeds premixed fuel through the normal Suzuki reed system; into the cylinder via a piston port and into the lower cases through a case reed. Engine cases are compact and small but the engine mounting won’t win any awards—the rear mounts w ith plates. Using the swing arm bolt and eliminating the plates is a stronger and simple way. Primary drive is by straight-cut gear and primary kick starting is standard, a first for open class Suzuki dirt engines. The multi-plate clutch runs in cooling oil and has a pleasantly easy pull. When pulled, it disengages completely and doesn't chatter or jerk when released.

A five-speed transmission has perfect enduro ratios. Low isn't overly low but the bike will climb anything climbable without slipping the clutch and fifth will scare

almost any clear thinking rider. Shifting is smooth and positive and neutral fairly easy to find, nice when waiting for your turn at that killer hill. The big Suzuki has another first—a ribbed kick start lever at last. The lever grips muddy boot soles and eliminates a lot of cussing when the going gets gooey. Only problem with the unit is its length. A person with a large boot will hit the top of his instep on the footpeg unless he uses the ball of his foot on the lever. Ignition is supplied by an external flywheel CDI unit that laughs at water and needs little or no maintenance.

An aluminum skid plate wraps tightly around the engine's lower cases but leaves part of the flywheel cover unprotected. Otherwise it is a nice plate.

The first glance at a PE400 will tell an enduro rider the bike was designed by enduro racers: ground clearance is good, bolts and nuts are sized so most items can be worked on with a 10, 12 or 17mm wrench, hand levers are protected from mud with covers, fenders are wide and long, the seat is wide and thick and comfortable. the silencer has a forestry approved spark arrester, lights are enduro legal and the wheels are quickly removable.

Just saying the wheels are quickly removable doesn't give the design engineer proper credit. Both can be removed quicker than any enduro bike we have ever tested. The front has a pull bar to remove the axle and loose parts amount to a 17mm axle nut and one spacer.

But the rear wheel is the great one. Removal of the rear wheel takes a slow person about 15 seconds! Honest. The design is a version of the older Husqvarna enduro rear wheel. The wheel plugs into a sprocket, eliminating the need for chain removal. Wheel adjusters stay in place and the axle threads into a stationary nut. To remove the w heel, the bike is laid on its left side, the 17mm axle end is turned counterclockwise and pulled out. then one large spacer is taken out and the wheel lifted about one inch and removed. Installation is a reversal of the removal procedure and easier to do than describe. The idea isn't a totally new one. just one that has been honed to a sharp edge and simplified. The plug in system uses cush rubbers to damp shock but don't despair-the cush pads won’t go away like older designs because the cush pads have metal bonded to the centers to prevent destruction and to spread the load. We put twelve hundred> miles on our test bike and had no problem with them.

The owner’s manual that comes with the PE400 is generally good and shows complete engine disassembly but don’t consult it about removing the rear wheel. The technical writer obviously didn't have the foggiest idea, and the written procedure tells the unknowing to remove the drive chain and disconnect the brake cable, then loosen the sleeve nut. then remove the wheel assembly with the axle shaft. The wheel is impossible to remove if the instructions are followed. None of the above things need be touched for wheel removal and in fact, have nothing to do with the removal. The only thing that needs removing or loosening is the axle—and the instructions never tell you to loosen or remove it. So, beware. Follow the procedure we described here and with practice removal can be cut to less than 10 seconds.

The throttle is a straight pull design. It looks like a Magura copy made from plastic. Like a Magura. the cable can be changed from the outside without disassembly. Unlike a Magura, the unit looks fragile, and is. A dead stop tipover broke off the cable snout. Luckily we had some trick 4-min. epoxy along and did a quick repair. It's designed around a gear drive and sealed nicely with an O-ring. But the only thing that holds the grip piece on is an extension of the top cap. also plastic. Better pitch it and put on a Gunner or Magura before it lets you down on the trail.

Foot controls aren’t up to the rest of the bike’s development. Ehe cost accountants must have stepped in. The brake pedal is saw-toothed but doesn't fold, the shift lever is steel and doesn't fold. The brake can be bent back if it is snagged and won't cause major damage. The shift is a different matter. If it smacks a rock, internal transmission damage can result. We replaced it with an International Motor Sports folding unit.

The PE400 frame is made from chromemoly steel and shaped much like the RM frames. A large single downtube splits into two smaller tubes under the engine, forming a wishbone. A large diameter backbone is strengthened by a small tube forming a triangle and the steering head area is heavily gusseted. The seat rail tubes leave the backbone tube and go back to form a loop for the rear fender. The upper shock mounts are formed by a couple of short tubes that weld to a large vertically placed tube that butts into the wishbone tubes behind and below the engine. The junction of these tubes is strengthened on the left side by a short curved tube and by a flat plate on the right. RM-style footpegs are mounted to these supports and offer excellent grip to muddy boot soles. The healthy return springs ensure they won't stick in the up position. A folding side stand, also like the RM's, is bolted to the left side and the return spring is strong and> placed on top of the tubing w here rocks can't prune it off.

An extruded aluminum swing arm is standard and provides excellent strength and good looks. Shock placement is semiradical for an enduro machine, with the lower mount several inches ahead of the rear axle. An RM-type chain guide is mounted close to the rear sprocket and uses plastic chain rollers. The unit is made from aluminum and doesn't protrude anv lower than necessary. The front of the arm has a protective rub block that wraps around the top. front and bottom, to keep the chain from sawing on it. It holds up well but is very noisy. A small plastic guard is mounted between the rear wheel and the chain to deflect mud throw n from the rear wheel.

Both wheel assemblies are good units that are properly designed and shouldn't cause problems. The front brake is large and powerful, although it took several outings before it seated fully. The rear brake drum has been moved to the same lefthand side as the sprocket, and is activated with a cable. We're not crazy about rear cable brakes on dirt bikes, but the PE’s cable has a large diameter woven wire center that’s teflon coated and provides feedback equal to a rod. The rear backing plate is hooked to the swing arm and doesn't float but doesn’t chatter either. The system is sound engineering for an enduro bike—a full-floater is easily snagged on tree roots and rocks; nothing can snag on the PE. W heel sizes are accepted standards; a 3.00-21 front and 5.10-18 rear. Our bike came equipped with new model K.290 Dunlops. Both worked well in mud but control is poor on dry and even damp ground. The front is particularly bad —it will grip well in some corners, just good enough to give the rider confidence, and then skate without warning. We threw it away and installed a iVletzeler.

The 400 has 9.8 in. of fork travel and 10.1 in. of rear w heel travel. The forks look like shortened RM units and have good rubber boots. They are air/oil/spring jobs providing good control and adequate travel for the bike’s intended use. Triple clamps have wide clamping surfaces and the top clamp has rear-set handlebar pedestals. The shocks are KYB non-reservoirs with dual springs. Spring preload can be adjusted to three positions but damping isn't adjustable and the shocks can't be rebuilt.

Suzuki’s nitty six-day wrench has been updated and now contains a removable 12mm end wrench w ith an axle puller pin. The smaller wrench connects quickly to the rrïain wrench that has been standard for the last couple years. The complete wrench will fix or adjust many pieces of the PE. The largest end loosens the axle adjuster sleeves, the other end removes the spark plug and the back side of the plug wrench fits both axles. The 12mm wrench adjusts the rear axle and handlebars, tightens the engine bolts and many other attached parts. A definite effort has been made at using as many 12mm sized nut and bolt heads as possible. The wrench is mounted to the right side of the triple tree and it's quickly removable.

Fenders, tank, headlight/numberplate, and side number plates are good quality plastic. The side plates are rear-set although most enduro riders don't use side numbers. The gas tank is the same 2.8 gal. part used on PEs for the past couple of years. It has a stepped bottom and places the fuel's weight low on the bike. The peteock is a simple on/off device—some testers liked it. some prefer a reserve. The tank has worked well on PE 250s and 175s. but isn't large enough for the 400. The odometer showed 53 mi. when we ran out of gas on the first ride. The loop included fast trails, sand washes, rocky low gear trails and fiat-out fifth gear terrain, so a really fast course would probably mean an even shorter distance could be covered.

We were excited about riding the big bore PE but somew hat disappointed once riding. The PE turns slowly and the steering is best described as sluggish and inaccurate. Suzuki delivered the bike with the top of the fork stanchions flush with the fork crown, so we did some measuring and decided to experiment with different height adjustments. The distance between the bottom triple tree and the top of the fork slider measures almost 12 inches so the stanchions can be safely moved up a couple of inches. We moved them up one inch for starters. The improvement was noticeable but the steering was still slow. We stopped beside the trail and adjusted them up another inch for a total of 2 inches. The bike responded by going through the bumps w ith a bucking motion and the steering was better but not nearly quick enough for tight woods use. Since the bucking motion was less than desirable. we ended up with the stanchions adjusted 1.5 inches above the top clamp. Straight line stability is good but the steering still exhibits a sluggish indifference to rider input and it’s hard to tell where the front w heel is. Placing the front wheel next to rain ruts or steering between buried rocks at speed is impossible: the bike controls its own position in tight areas. The rider can direct the PE's general direction and position down to a width of about 12 inches, then the bike takes over and goes where it wants. Very unnerving when the front wheel placement makes a difference between following a precarious trail or running off it. Forget about trying to keep the bike above rain ruts w hen the trail has a side slope to it—may as well aim for the rut-the bike is going to end up in it anyway. Best to enter at a spot you choose. These tactics on the bike’s part quickly cause arm seizures and an uptight, uneasy rider. Steering precision improved with the

3.25 Metzeler but no lire is going to quicken steering. After the second test session an inspection of the bike turned up a cut casing on the rear tire and we replaced it with a Dunlop K88HT. The complete tire swap added control to the PE but the steering still has a delayed and remote feel to it.

The rest of the package is good for a first year model: Brakes are strong and progressive. Both brake arms have external return springs so mud doesn't slow or prohibit the return. The silencer is strongly mounted and quiet although it isn't repackable. The foam air cleaner is in a good plastic airbox with a top that diverts water from its

opening. Clutch pull is a one finger procedure and the primary kick starting simplifies restarting in a mud hole or on a side of a hill. The seat is wide enough to be comfortable for 100 miles yet narrow enough so it doesn't rub the rider's legs. Lights are enduro legal and will get the rider in from the woods after dark it' caution is used.

The suspension is poor. The forks aren't as plush as the ones offered on. say. a Huskv WR or Maico E. They are a little harsh in the slow stuif and hop in the rough. Lighter oil helped but didn't end all of our test rider's complaints. The shocks have double springs w ith perfect spring > rates and marginal damping rates. They are fine for play and novice/C riders but a fast B or any A rider will soon override their action. When pushed hard the shocks don’t react quickly enough and the back wheel hops through the bumps. Strangely, the bike still stays straight and has no tendency to side step or swap. And fairly good control can be maintained, the ride just becomes rough and tiring.

SUZUKI

PE400

$1899

SPECIFICATIONS

DIMENSIONS

FEATURES

We learned more about the suspension by following the PE than riding it. From behind, the bike twitches constantly. Funny, the rider is never aware it is happening. The constant twitch is probably responsible for the uneasy feeling all our test riders noted. The suspension, especially the shocks, is responsible for the twitch.

The previously mentioned gas consumption is the only fault we could find with the engine. It is extremely smooth, doesn't vibrate at any speed and has power at any rpm. And the power is progressive and completely useable. In fact it has the most useable power output of any Japanese open class two-stroke we have tested to date. Power delivery' to the rear wheel is always smooth and predictable. But don’t try and follow one too close, the roost will knock you off your bike. Funny thing is. the PE400 rider is never aware the bike is spinning the rear wheel. This kind of power is great when that muddy enduro is raced. Slippery side slopes and greasy uphills don’t pose a problem w hen the mount has useable power like the PE400. The short-stroke engine is more versatile than the long-stroke RM engine. The PE will pull second gear from a near dead stop. even uphill, without a chug or whimper, and it’ll w ind like a 125 motocrosser if the rider desires. All this means the racer or play rider doesn’t have to shift every 10 feet.

The PE400 is a good first year effort but can’t be considered great due to its steering indifference and suspension quality. Suzuki’s national enduro team has had a good influence on the bike's development but we would guess their bikes turn better. Someplace down the line someone has opted for the slow steering geometry to satisfy the less serious rider. We think this was a mistake. An enduro bike has a need for quick steering. The rest of the bike is so nice we have decided to keep it around for a long range test, probably a vear. We’ll let you know if we come up w ith a cure for the sluggish steering.