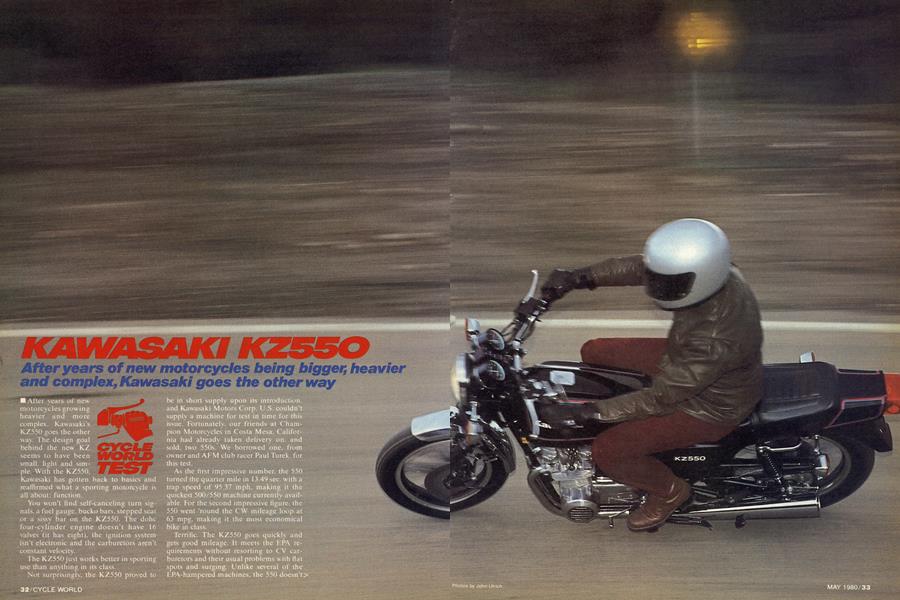

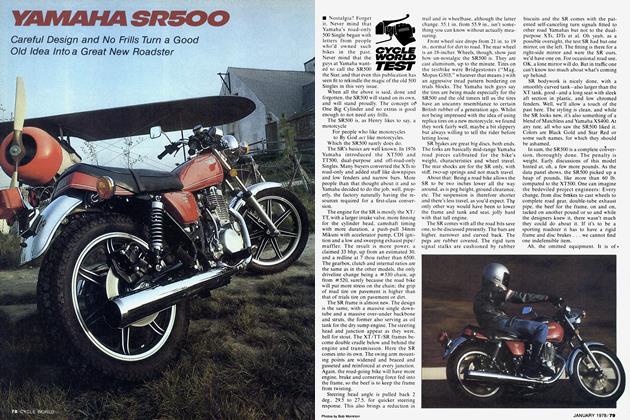

KAWASAKI KZ550

CYCLE WORLD TEST

After years of new motorcycles being bigger, heavier and complex, Kawasaki goes the other way

After years of new motorcycles growing heavier and more complex. Kawasaki’s KZ550 goes the other way. The design goal behind the new KZ seems to have been small, light and simple. With the KZ550, Kawasaki has gotten back to basics and reaffirmed what a sporting motorcycle is all about: function.

You won’t find self-canceling turn signals. a fuel gauge, bucko bars, stepped seat or a sissy bar on the KZ550. The dohc four-cylinder engine doesn't have 16 valves (it has eight), the ignition system isn’t electronic and the carburetors aren't constant velocity.

The KZ550 just works better in sporting use than anything in its class.

Not surprisingly, the KZ550 proved to be in short supply upon its introduction, and Kawasaki Motors Corp. U.S. couldn’t supply a machine for test in time for this issue. Fortunately, our friends at Champion Motorcycles in Costa Mesa. California had already taken delivery on. and sold, two 550s. We borrowed one, from owner and AFM club racer Paul Turek. for this test.

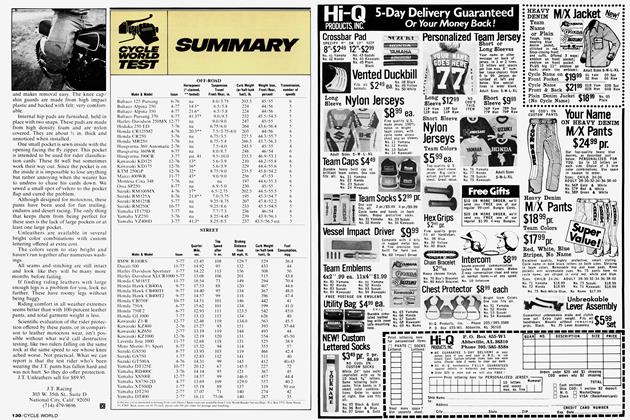

As the first impressive number, the 550 turned the quarter mile in 13.49 sec. with a trap speed of 95.37 mph. making it the quickest 500/550 machine currently available. For the second impressive figure, the 550 went 'round the CW mileage loop at 63 mpg. making it the most economical bike in class.

Terrific. The KZ550 goes quickly and gets good mileage. It meets the EPA requirements without resorting to CV carburetors and their usual problems with fiat spots and surging. Unlike several of the EPA-hampered machines, the 550 doesn’t> need special riding techniques to cruise around town.

The factories using CV carbs are using them because they perform well in emissions tests, and because lean jetting doesn’t give the cold-ride bothers common to some of the EPA-legal slide-throttle jobs.

So. In the same package, Kawasaki has provided power, economy, smoothness and done all the law requires. How?

The key is Kawasaki’s clean air injection system. It feeds fresh air, drawn from the airbox through a system of hoses, a oneway valve and two reed valve assemblies, into the exhaust ports in the head, where unburned hydrocarbons ignite upon contact with the oxygen in the fresh air. As the exhaust gas passes through port and the valve closes, a vacuum is created and it pulls in more clean air, so an air pumpused in many car engines—isn’t needed. The effect is simply reduced emissions at the exhaust pipe, without the problems associated with ultra-lean carburetion.

The 553cc KZ550 engine has a bore and stroke of 58 x 52.4mm, and is based on the European model Z500 introduced in 1979. The only difference between the European model 500cc engine and the America market 550cc engine is the air injection system used on the U.S. model and an increase of 3mm in bore size.

The 550 has 27mm intake valves and 24mm exhaust valves, with two valves per cylinder. The valve stems are just 5.5mm in diameter, both for light weight and minimal interruption of gas flow in the port. (For comparison, a KZ650’s valves have 7mm o.d. stems.) The valves are operated by double overhead camshafts with lobes riding directly on valve buckets, with adjustor shims located on top of the valve stems, underneath the buckets. Like the similar KZ650 engine, the buckets must be removed to reach and replace the shims for valve lash adjustment purposes, and like the 650, the camshafts must be removed before the buckets can be pulled and the shims replaced.

But while that system has maintenance disadvantages, it has three advantages. First, since a small shim is used underneath the bucket instead of a large shim held on top of the bucket by a lip, the shim cannot be kicked out of place (and through the cylinder head casting) by the lobe of a radical aftermarket hop-up camshaft (stock cams kicking a shim isn’t very common). Second, the smaller shim weighs less than a large top-mounted shim, so valve train weight is reduced and valve control at high rpm is improved (although that’s not a factor using stock cams at the stock redline). Third, because the system is very stable, valve adjustments are generally not required as often as in the case of a conventional screw and locknut adjustment system.

The camshafts are connected to the crankshaft by a narrow Hy-Vo cam chain, and an automatic cam chain tensioner is used. As the cam chain wears and slack increases, a spring-loaded tensioner bar moves forward, bearing on a long shoe which contacts the chain. Another springloaded bar comes in at a right angle. Each bar is wedge shaped at the point of intersection, and as the tensioner bar advances, the lock bar’s wedge tip moves underneath the tensioner bar’s wedge tip. keeping the tensioner push bar from retreating. A rubbing block in the cam cover bears on the chain between the intake and exhaust cams.

The intake valve in each combustion chamber is recessed, creating in effect a ridge around the edge of the valve closest to the spark plug. That ridge increases the velocity of the incoming fuel mixture as the intake valve opens, helping to efficiently fill the cylinder at slow engine speeds while increasing mixture turbulance and flame speed at all engine speeds.

Another neat touch here. Because the 550 breathes well and develops good power without resorting to hyper-tuning, the valve timing can be designed to work well at relatively low revs. The 550’s intake valves open at 20° BTDC and close at 48°ABDC, while the exhaust valves open at 48°BBDC and close at 20°ATDC, for a duration of 248°, measured at 0.3mm lift. Mild indeed. Lift for all valves is 7.3mm.

The end result is that the KZ550 makes about as much peak horsepower as say. a GS550 Suzuki but has much more midrange and low-rpm response and power with better fuel economy as well.

(If the whole idea of improved cylinder charging, shorter cam timing and improved torque sounds a lot like the touted benefits of the TSCC—Twin Swirl Combustion Chamber—system used in Suzuki GS450, GS750 and GS1100 engines, that’s not surprising. What we’re seeing in the case of the KZ550—as we saw in the case of the Suzukis—is combustion chamber design used to significantly accentuate the swirl and turbulance found in all engines, and to use that swirl to improve volumetric efficiency at usable engine speeds. At least one wag, comparing the Kawasaki system to the Suzuki method, referred to Kawasaki’s “ Single Swirl Combustion Chamber.”)

The rest of the Kawasaki engine is straightforward and conventional. Pistons are slightly domed, producing a 9.5:1 compression ratio. The crankshaft is forged one-piece, with plain bearings.

Power from the crankshaft is transferred through a Hy-Vo primary chain to a jackshaft. which drives the clutch basket b> gear. The KZ550 clutch has the same number of plates as the KZ650, but has a smaller o.d. and thinner plates. Yet the width of the contact surface area on the drive plates is actually wider, measuring 11.5mm to the 650’s 11mm. The steel driven plates are smooth, without the usual spanking die dimples. The clutch hub is secured to the splined end of the input shaft by a large nut which has been pressed into an oval shape—it takes a big wrench or an air gun to remove the nut. but chances are slim it’ll ever come off on its own.

Kawasaki engineers did another unconventional thing with the internal gear ratios. Everybody knows that close-ratio gears are used in racing, so the normal technique is to provide close ratios for the road, whether needed or not.

The KZ550 has relatively wide ratios, in particular the jump between 5th and 6th. where the difference is a whopping 21 percent. (For comparison, the jump from 4th to top (5th) on the KZ650 is 14 per cent.)

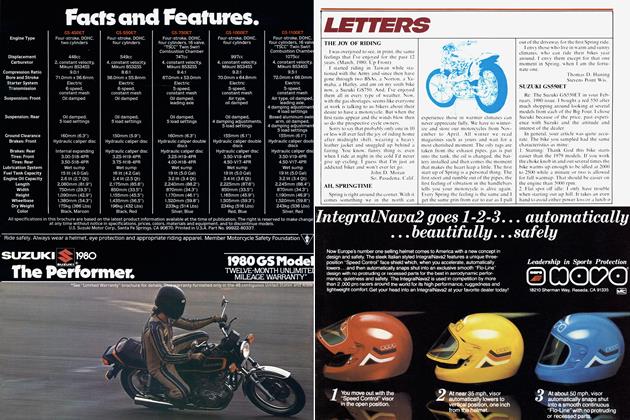

The lower five of the 550’s six speeds are lower than, for example, the ratios of the rival Suzuki GS550. Overall, the KZ goes 6.25.7.06, 8.31, 10.14, 13.08 and 18.89. For the GS, it’s 6.30, 6.89, 7.73. 9.09, 11.71 and 17.57.

Now. What this means is that the GS ratios keep the engine from having to speed up or slow down a lot when the rider is shifting, i.e. the engine can be held at peak. The KZ has more of a jump and the engine could fall off the cam. as the racers say.

Except there is no cammy. peaky power band to fall off of. Instead, the KZ is turning more revs in the intermediate gears at the same road speeds, which means more acceleration, while in top gear both the GS550 and the KZ550 are running at the same engine speeds. The KZ gets good acceleration through the gears and doesn’t have to buzz on the highway.

An interesting feature of the KZ550 transmission—as well as other Kawasaki gearboxes—is a neutral lock-in. Three ball bearings are positioned inside the output shaft’s slider fifth gear, which moves to engage first gear. When the output shaft is moving, i.e.the bike is rolling, the three balls are thrown to the outside of their cavity. If the shaft isn’t moving, at least two of the balls fall against the output shaft.

What this means is that when the rider rolls to a stop in first gear and pulls up on the shift lever, the transmission will only go into neutral. The balls have dropped into a bevelled groove and the shift drum can’t rotate any farther. When the bike moves, though, the balls are spun clear and the drum will rotate.

Mixed reviews here. This does mean you can’t possibly not find neutral when you want it. Just go to first and pull up.

On the other hand, suppose you want second and the bike is stopped? What if the battery is flat and you want to bumpstart the engine? Like the clutch lever lockout, the no-reserve petcock and a few more, it’s a clever idea for which we haven’t heard a demand.

The KZ550’s countershaft sprocket is held on the output shaft’s splines by a plate and two 6mm bolts, instead of the previously-used giant nut. That means that owners wanting to alter gearing won’t have to have a 27mm socket and a breaker bar to change the sprocket.

Ignition is conventional breaker points firing 12mm spark plugs. No. points aren’t as “trick” as an electronic ignition, and yes. they will require maintenance at regular intervals. But on the plus side, points ignitions don’t have a potted-in-resin black box to go bad in the middle of nowhere and can more easily be repaired on the road in case of failure. A points system is also cheaper.

The important thing about the ignition system is not what it is but that it works. And since coils determine spark intensity, an electronic switching system replacing the points wouldn’t necessarily mean a hotter spark at the plugs.

Like the rest of the bike, the KZ550 chassis is simple and straightforward. The frame has a single backbone with double downtubes. with heavy bracing at the steering head. Rake is 26°, trail 3.9 in., wheelbase 54.9 in.

The front forks have 36mm stanchion

tubes (same size as the 650 and 1000 stanchion tubes) and the front axle is positioned in front of the sliders. The swing arm is tubular steel and shocks are conventional dampers with spring preload adjustments only. The leading axle front forks yield 6.0 in. of travel, while the rear wheel travels a maximum of 3.7 in.

Tires are Japanese Dunlops, a 3.25-19 ribbed F7 in front and a 3.75-18 TT100 K81 in the rear. That’s an interesting combination in light of recent Dunlop advertisements featuring tire engineer Tony Mills advising against mixing tire profiles. The K81 has what Dunlop calls a “Trigonic” profile, which means that it is more triangular in profile than the rounded F7 front tire. We asked Mills about the tire combination of the Kawasaki. According to him, the combination is not ideal, but if tires must be mixed, it is better to fit the rounder profile in front, as Kawasaki has done. Mills had no explanation as to why Kawasaki would pick that combination of tires. We don’t either.

Brakes are a single, drilled 11.6-in. hydraulic disc in front and a 7.0-in. drum in the rear. The front brake pads have a very high metal content to improve wet weather stopping performance.

As always, it’s how the chassis and engine work together that counts, and the KZ550 is a good partnership. Because the bike has a relatively light weight, (442 lb. ready to go, vs. the Suzuki GS550’s 467 lb.), short wheelbase (54.9 in. compared to the GS550’s 56.5, the SR500 Yamaha’s 55.5, the Laverda 500 Zeta’s 55.1). steep rake (26° vs. the GS550’s 29°,) and short trail (3.9 in. to the Suzuki’s 4.7), it feels light and steers quickly. The first impression is that it is a very small motorcycle. Changing direction around town is a snap. Turning around in the parking lot or getting out of the garage is not the wrestling match it can be with long-wheelbase, heavy, big motorcycles. Low speed handing is perfect.

As nimble as the 550 is around town, once the suspension is set correctly. the> Kawasaki is also stable at top speed in a straight line and at a fast pace on canyon roads.

But when the rider really starts to push, some flaws show up. To evaluate high speed handling safely, we took the KZ550 to Riverside Raceway and flung it around the road course.

The KZ550 wobbled after hitting bumps in fast, sweeping turns with the shock preload set at maximum. After a pit stop to reset the preload to the third of five possible positions, the bike stopped wobbling. When setting up suspension, assuming that the motorcycle does not have a serious cornering clearance problem, it’s best to try for achieving maximum suspension travel possible without setting the suspension too soft. With too much spring rate or spring preload, the suspension won’t react to bumps and dampen the shock, and a wobble can result. Too little preload or spring rate can result in the suspension bottoming constantly and wobbles starting as the suspension hits bottom. The goal is somewhere in between.

The Riversides esses can be taken flatout on a bike of the Kawasaki’s size and speed, but the front end flexes in transitions from left to right to left. The rider can feel a delay in steering as he levers on the bars to make the motorcycle turn. What feels like a delay in steering reaction is actually the front end twisting under handlebar input before moving the front wheel.

At high speed the gyroscopic effect of the spinning wheel acts to hold the wheel upright and straight, so it takes more force to turn the wheel—and thus the motorcycle—as speed increases. In town or at lower speeds, the 550 feels fine.

The high speed flex seems to be coming from the willingness of the forks to twist between the axle and the clamps.

Most of the time, the flex won’t be felt because most of the time most of us plain aren’t riding at the limit. Even on the track it won’t be too much of a handicap. Riders will adapt, just as they have to other flexing fronts in the past.

The flex appears to be a matter of not having enough resistance built into the front axle mount, or the triple clamps, or both. A matter of wanting to keep the weight down, perhaps, or of building leading axle forks to a competitive price.

What makes the KZ550 work as a sports bike is its light, predictable behavior in slower speed corners, where it’s possible to turn at any point the rider wants and pick any one of many lines. Passing traffic? No problem. A moving chicane in mid-turn can be ridden around or underneath without trouble.

The Kawasaki doesn’t have to be fought into, around or out of a curve. It will dive in and out instantly.

Cornering clearance is exceptional. helped not only by the positioning of the footpegs and stands, but also by the narrowness of the engine across the crankcases, including the alternator and ignition covers. The KZ550 powerplant is 19.5 in. wide, a full inch narrower than the Suzuki’s 20.5-in. width.

But the cornering clearance cannot be used to full advantage because the KZ550’s tires slide along before anything more substantial than the rubber footpeg covers touch down. Even dragging the pegs is risky with the stock tires, and when pressed further the Kawasaki’s rear tire

breaks loose and the back begins to come around. In fact, the only time we scraped the centerstand was with the 550 leaned over and almost full-lock sideways on Riverside’s downhill, lefthand Turn Seven. The rider was pleased to finish the turn upright.

The tires didn’t do well in braking tests either. Anybody interested in riding a KZ550 hard on twisty pavement should begin planning to replace the stock tires with Pirelli Phantoms, Metzeler Perfects, Dunlop K81 Mk. Ils or some other high performance tire.

And unless that sporting riding will be done in the rain, the KZ550 pilot should replace the stock front brake pads with pads for the 1977-78 KZ650. The 550’s pads work in wet and dry, but they aren’t as good in the dry as are pads with less metallic content, being more likely to fade under hard use.

For those in rainy climes, the 550 pads will be best. For daily use it’s better to have good stops under all circumstances that to have super stops dry, perhaps stops wet.

(As a side note for Kawasaki owners, under no circumstances should the owner of a 1978 or earlier KZ install 1979-80 high-metallic-content pads. The ’79-80 calipers have a built-in heat sink to carry away the heat generated by the metallic pads. Earlier calipers lack this and late pads in early calipers could lead to trouble.)

Where the 550 absolutely shines is in engine performance, from lowend and mid-range torque that would do a normal 750 justice to the fastest 550cc E.T. That engine torque means the 550 will come off corners hard or cruise around town at low rpm (2500-3000) in top gear. In an impromptu roll-on from 50 mph, the KZ550 in sixth gear left behind a 1340cc HarleyDavidson FLT 80 running in fourth gear (the Harley has five speeds). The ability to happily purr along at low rpm in higher gears has a lot to do with the bike’s good gas mileage.

Combined with the light weight and quick steering, the impression the rider gets from the KZ550’s engine is that he’s riding a 400 with 750 power. .

At the dragstrip the 550 turned 13.49 sec. at 95.23 mph in the quarter and reached 109 mph in the half-mile. Through eight hard passes complete with burnouts and power shifts the engine never complained and the clutch didn’t slip or grab.

It might seem that with the amount and broad spread of power the KZ550 engine generates, the machine would be good for touring. There’s nothing to stop a KZ550 owner from heading for Daytona on a KZ550, but because the bike is oriented toward sport use, it isn’t particularly comfortable. The suspension, which does a good job at speed, is not as compliant as the suspension found on many bikes, which means that small, repetitive bumps like concrete highway expansion joints aren’t absorbed, but passed on to the rider. The seat is narrow, although not excessively hard. It’s also flat, not stepped, an advantage for the rider who wants to shift weight and move around while riding. The footpegs were too far forward to suit two staffers, one 5-foot-10, the other 5foot-11. But one 6-foot-2 staff member liked the seating position just fine, and didn’t find himself riding the bike with feet placed on the passenger pegs, which is what the shorter riders did.

More important than a discussion of seating position preferred by various sized riders is the fact that the KZ550 has the basics all there in working order. Its superb engine and quick steering combined with high-speed stability make it the best sporting mount of its size, even though the OEM tires and brakes are definitely not high-performance oriented.

In road racing organizations with an appropriate displacement class breaks, the KZ550 will rule the box stock and production classes. For riders not into pavement competition, the 550 will only deliver many thrills, much fun and excellent economy. It is proof that bikes don’t have to get heavier and bigger to get better, and if this is the way it’s going to be in the future, sign us up for another 50 years of riding motorcycles. Ö

KAWASAKI

KZ550

$2179