MONTESA COTA 349

CYCLE WORLD TEST

After current U.S. trials champion Marland Whaley rode a stock Montesa Cota 349, he asked the factory if he could have a stock cylinder for his competition machine instead of the trick cylinder he had. The stock machine ran better, he thought. Trials must be the only form of motorcycle competition where a factory rider will demand a bike just like the ones sold to the public.

We’ve become so accustomed to the brochure saying “just like a works bike,” we’ve almost forgotten what the words mean. They do apply, however, to the 1980 Montesa Cota 349, the most demanding and serious trialer Montesa has yet made.

American motorcycle riders began to notice Montesa in the late I960’s and their reputation for reliability and torque was quickly earned. The first Cota arrived in the U.S. shortly thereafter and trials riders had a marque other than Bultaco from which to choose. The two Spanish trialers have pretty much dominated the trials world since, except for challenges from the Japanese when the great trials boom was about to happen.

The trials explosion never materialized and the Japanese companies cut back or discontinued production of their trials bikes, which left the market to Bultaco and Montesa with a few Ossas on the fringe.

Having tested every really new Montesa Cota over the years, we were interested in the new frame and larger engine of the 349.

The change is more than the numbers indicate, because the Cota 348 had a displacement of only 305cc. while the 349 has an actual 349cc. Displacement aside, the 349 is. like the earlier versions, a basic two - stroke Single, with piston ports, no reed or rotary valve, and has an uncorrected compression ratio of 8.5:1.

European manufacturers using the full stroke of the piston to figure compression ratio, the Montesa’s 8.5:1 compression ratio is really quite mild. Normal European c.r. would be 10:1 or 12:1. Coupled with the mild compression is port timing that gives maximum low-end grunt and a top end that’s hardly noticeable.

Making the Montesa Trialer More Competitive Means Making it for Experts Only.

Surprisingly, the Montesa owner’s manual specifies 96 octane fuel (though not saying by which octane rating system), which seems unreasonably high. Never mind, though, because the Montesa ran fine on any fuel we could put in it.

The 26mm Amal carburetor allows the big motor to pull cleanly from idle up through top revs and even though we felt the carburetion was a bit on the rich side at first, we later came to believe the jetting was quite close. The bike always started on the first kick unless we dropped it and allowed the engine to flood and even then only three or four kicks were necessary to bring it to life. The spark is provided by a Motoplat flywheel magneto with points and the unit proved to be trouble free and waterproof while we had the bike.

The exhaust pipe leaves the center of the cylinder and loops up and between the twin down tubes before crossing over the head and carburetor where it passes through two silencers. The exhaust note is very quiet and. except for the final silencer, is out of the way. We managed to ding the rear silencer and serious competition will shorten its life more.

Transmissions on the older Montesa Cotas had a reputation for jumping out of gear at the worst possible moments, but with the new' constant mesh six-speed this problem seems to be history. Neutral was difficult to find and more than once we had to kill the engine to do it. Granted the test bike only had eight miles on the odometer when we got it and the transmission may loosen up a bit, it was a bother.

The shift lever makes the Cota’s role in life trials perfectly clear. It’s a sturdy piece of cast alloy, mounted high so as to keep out of harm’s way. and well forward, like perhaps 12 inches, of the peg.

Putting the lever out of harm’s way also puts it out of toe’s reach. On purpose, so the rider can’t possibly nudge the gearchange while under way.

Which also means the normal rider can’t reach the lever with his toe unless he lifts boot from peg and moves toe forward a couple of inches.

On the trail, between sections, it’s a bother. In a section, it’s impossible. The Cota rider quickly learns to select a gear for the section, and to stay in that gear. Or else.

Luckily, though, the first three speeds are quite close together. Any of them will get you through and the engine is so deliberately non-peakv that pulling power is always there.

The starting arrangement, like that of the Sherpa T. is both awkward to use and of the non-primary variety—that is. you must select neutral before starting the engine. More than one trials rider would like to see Señors Bulto and Permanyer get around to providing primary starting on their respective bikes. The righthand side kickstart lever is short and folds far forward so it must be held down before a boot can reach it

A new' frame goes with the new engine for 1980 and the most obvious change is the elimination of the frame tubes under the engine and the aluminum plate that takes their place. The skid plate not only protects the new magnesium side cases but serves as a structural member as well. The rear motor mount extends well down and provides beefy support for the rear of the skid plate and the entire concept appears able to withstand the rigors of rocky sections.

We got conflicting reports on the frame material from our sources at Montesa but w'e suspect mild steel still provides adequate strength on the new' bike. It seems as though some manufacturers are reluctant to admit using mild steel when others are bragging about chrome-moly. A lot of riders would rather have a quality mild steel for a frame rather than paper thin chrome-moly that will crack after the first few hours of hard riding. Whatever the material, the rear frame loop behind the seat has been eliminated for 1980 while the swingarm has been lengthened by 1.5 in. and gives the Cota what must be the longest wheelbase in the trials world. Turning radius doesn’t seem to be much affected as far as we could notice but the extra length certainly helps on those rocky steps. Suspension is certainly not state-of-theart as compared to motocrossers but then trialers have rejected super-long travel suspension units as being impractical. The front forks on the new Cota are still built by Montesa and they continue to use a s.quare section on the sliders to save weight. New for 1980 are the air valves at the top of the fork tubes and we used 8 psi during our riding and even in the trials meet. The factory recommends using between 8 and 12 psi for trials work and except for the seals being a bit sticky, forks seem near perfect for their intended use.

The rear units are a different story. Both seals blew' during the first 50 miles of testing. The spring rates and valving seemed satisfactory for trials work but the Telesco units should last more than one trials meet.

Pirelli MT 13s with DOT numbers on the sidewalls are supplied with the bike, indicating the tires are street legal. Street legal trials tires or not, it’s nice to see competitive tires on the bike right out of the box. We ran 4 psi in the rear and 5 in front for both our testing and our trials meet. The tires are laced to Akront unflanged aluminum rims with a conical hub in the rear and a small, finned unit in the front. The brakes worked without fault and most riders like the feel that is so important on the slippery downhills.

Montesa has been using the larger diameter (1.0 in.) handlebars for several years now' in order to provide additional rigidity and the front end of the new' bike seems to be as rigid as anything. No twisting was noticed in the slow rocky sections and except for the bars being on the low side for our six-foot test riders, we liked the bend. The beloved Renthals are still in use on the Cotas at trials meets and spacers allow the smaller % in. bars to be used without difficulty.

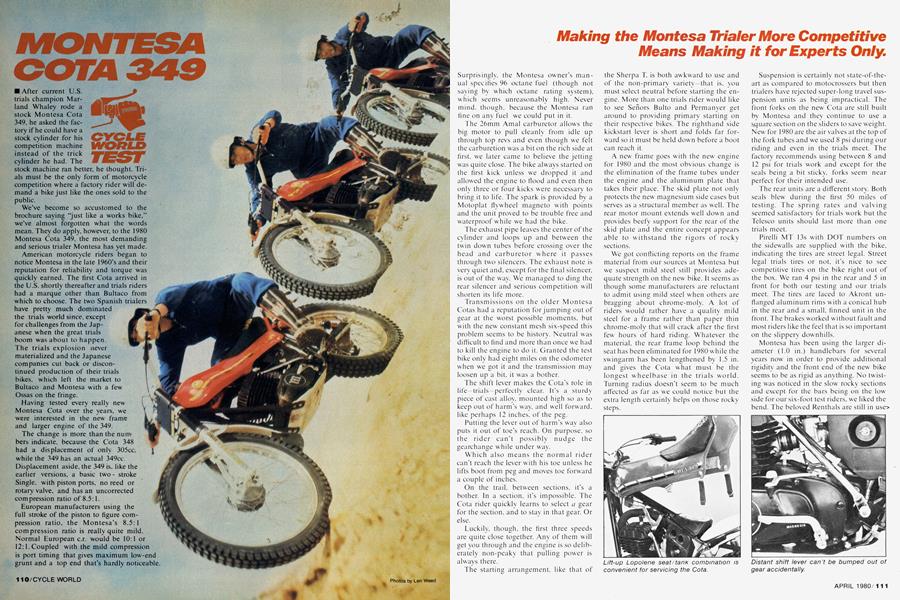

The attractive gas tank and seat is made of a new material. Lopolene is the trade name of a nylon material that allows both a glossy finish and moderate flexibility. Since fiberglass tanks are illegal in many European countries, the Lopolene seems to satisfy both aesthetic and legal parameters. New for 1980 is a plastic fuel gauge tube recessed into the right side of the tank, reminiscent of early Japanese street bikes, which allows riders to quickly determine the amount of fuel remaining in the 1.4 gallon tank.

As in the past, the tank and seat are held down in the rear by rubber straps and a pivot at the front which allows the unit to be raised for access to the air cleaner and tool container. With the tank and seat in the raised position, the air cleaner can be removed in 30 sec. or so. Nice touch. Señor Permanyer. The seat is a bit more padded than that of last year’s Cota and we found ourselves sitting a bit more than usual when riding between sections. After measuring and weighing the bike, we rode our favorite trials sections and formed some initial impressions about power and handling, then entered the bike in an ATA trials meet, its natural habitat. We’re glad we did because several areas showed up that need further refinement by Barcelona.

We’re already mentioned the rear shocks but after dropping the bike while exiting a section, the throttle assembly cover flexed enough to allow the entire housing to fill with dirt. Before continuing we had to disassemble the unit, dig out the dirt and wash the parts with gasoline from the fuel line. A stiffen more secure cover is needed. Trials bikes will get dropped and competitors won’t always have time to stop and clean the throttle. The new lateral pull unit is excellent both in feel and concept but it does need improvement.

Gear box oil was leaking from around the shift lever shaft almost as soon as we began riding the bike and it managed to make quite a mess each time we rode. Most Montesa owners replace the countershaft seal with a doublelipped Yamaha seal to solve the problem, an inexpensive solution that should be unnecessary.

On the positive side, as mentioned earlier, power is impressive and more than once it supplied a bit more power than we were able to use. The throttle response is very quick for a trials machine. Novices and perhaps a few amateurs are going to have a hard time getting used to this. Compared to the smoothness of a Sherpa T, the Cota will be a handful for beginning trials riders and if the power isn’t a problem for the beginners, the steering certainly will be. During testing of the Sherpa T we mentioned that the Bultaco could be trusted to non-trials riders without too much worry. Not so with the Cota, for quick steering and a sensitive throttle wàll likely put the beginner in a reverse lock situation and force a quick step over the handlebars. It happened more than once during testing and as you’d expect, once or twice in the trials meet. It’s apparent the Cota was built for experienced trials riders who have mastered the delicate art of throttle control and steering geometry that allows very little room for mistakes.

MONTESA

COTA 349

$2295

Trials riders are like any other kind of bike nut; they notice the latest things and wonder about them. The owner of a 1979 Cota 348, the 305cc version remember, was practicing where we were and spotted the ’80 model. So we swapped machines.

First thing we noticed was that it was much harder to keep the front wheel of the older Cota on the ground, the result of the shorter swing arm. There seemed to be less power, and throttle response wasn’t as crisp.

The ’79’s owner was much less scientific. He came back with a grin from ear to ear, and the comment “I gotta get me one of these.”

Ridden by Southern California Expert Oli Thoradson, the new Cota enabled him to clean sections he was having trouble with on his year old 348 Cota. He appreciated the longer swing arm and extra lowend power on steep rocky climbs where the earlier Montesa was harder to keep on both wheels.

Other features the Montesa owner will like include the rubber cover over the quick-detach countershaft sprocket. By depressing a spring clip with a screwdriver, the countershaft sprocket can be pulled almost instantly. While there isn’t much need for changing sprockets in most American trials, on longer events such as the Scottish a quick change sprocket would be worthwhile.

How close the stock 349 Cota is to the world’s best trials bikes becomes apparent looking at serious competition machines. The 349 ridden in international competition by Mark Eggar only has a narrower kickstart lever from the motocross Montessa and a narrower shift lever added to a stock bike. Other than those changes, it’s exactly what a customer would buy from Montesa.

We don’t know if Bultaco builds its machines to stay ahead of its cross town rival or if Montesa tries harder being Number Two. Whichever, the trials world is better off because of the competition, and we can’t imagine trials without both companies.

Even with its few shortcomings, the Cota is capable of winning right out of the crate, just like the Sherpa T. It’s not a play bike, nor should it be. If it were any less specialized, it would be less competitive. In trials, there is no room for that.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue