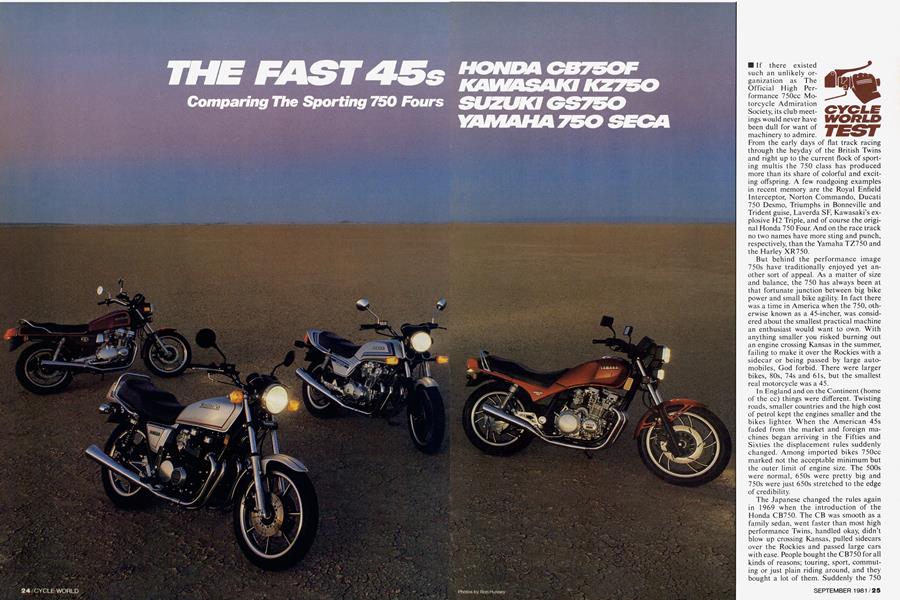

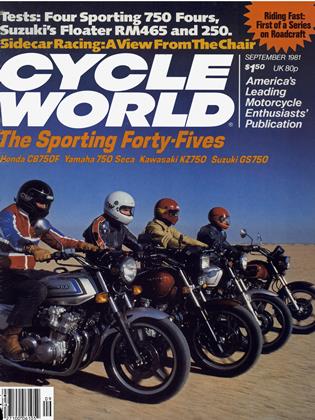

THE FAST 45s

Comparing The Sporting 750 Fours

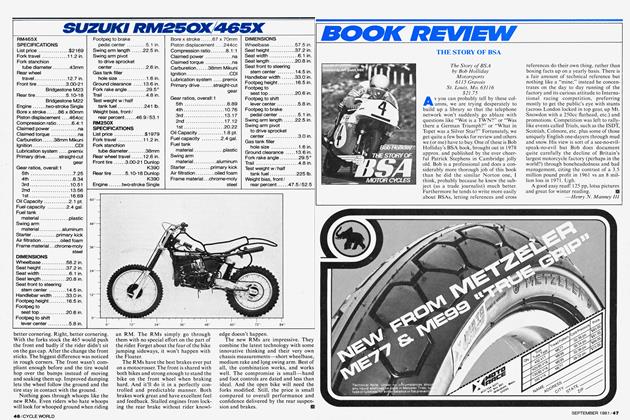

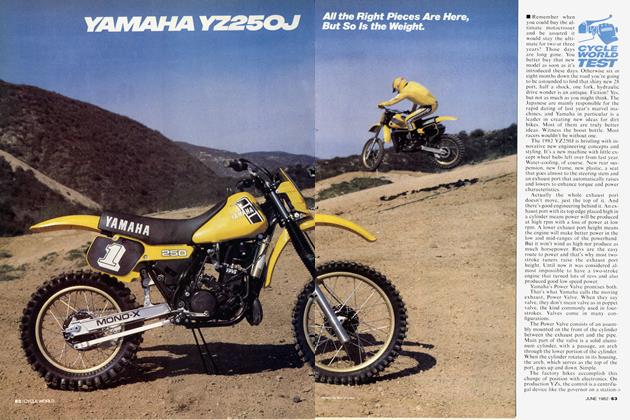

CYCLE WORLD TEST

HONDA CB750F KAWASAKI KZ750 SUZUKI GS750 YAMAHA 750 SECA

If there existed such an unlikely organization as The Official High Performance 750cc Motorcycle Admiration Society, its club meetings would never have been dull for want of machinery to admire. From the early days of flat track racing through the heyday of the British Twins and right up to the current flock of sporting multis the 750 class has produced more than its share of colorful and exciting offspring. A few roadgoing examples in recent memory are the Royal Enfield Interceptor, Norton Commando, Ducati 750 Desmo, Triumphs in Bonneville and Trident guise, Laverda SF, Kawasaki’s explosive H2 Triple, and of course the original Honda 750 Four. And on the race track no two names have more sting and punch, respectively, than the Yamaha TZ750 and the Harley XR750.

But behind the performance image 750s have traditionally enjoyed yet another sort of appeal. As a matter of size and balance, the 750 has always been at that fortunate junction between big bike power and small bike agility. In fact there was a time in America when the 750, otherwise known as a 45-incher, was considered about the smallest practical machine an enthusiast would want to own. With anything smaller you risked burning out an engine crossing Kansas in the summer, failing to make it over the Rockies with a sidecar or being passed by large automobiles, God forbid. There were larger bikes, 80s, 74s and 61s, but the smallest real motorcycle was a 45.

In England and on the Continent (home of the cc) things were different. Twisting roads, smaller countries and the high cost of petrol kept the engines smaller and the bikes lighter. When the American 45s faded from the market and foreign machines began arriving in the Fifties and Sixties the displacement rules suddenly changed. Among imported bikes 750cc marked not the acceptable minimum but the outer limit of engine size. The 500s were normal, 650s were pretty big and 750s were just 650s stretched to the edge of credibility.

The Japanese changed the rules again in 1969 when the introduction of the Honda CB750. The CB was smooth as a family sedan, went faster than most high performance Twins, handled okay, didn’t blow up crossing Kansas, pulled sidecars over the Rockies and passed large cars with ease. People bought the CB750 for all kinds of reasons; touring, sport, commuting or just plain riding around, and they bought a lot of them. Suddenly the 750 was not a small bike or a big bike or a wild sporting beast, but just a popular all-purpose machine. It was the Standard Bike.

With that mantle of conservatism heavily on the shoulders of the 750 the performance game moved upstream during the Seventies. Bikes like the ZI, GS1000, XS11 and Honda’s own CBX and Gold Wing all took over from the Honda 750 as the motorcycles most likely to stun your friends and neighbors with their sheer unspeakable latent power. The CB, meanwhile, had gradually slipped into a sort of quiet backwater of good solid performance and durability without the old glamour and flair, despite a few sporty updates. Yamaha had a 750 Triple, a nice clean shaft drive bike, but not the kind of machine fevered dreams are made of. The Kawasaki H2 was the only real performer Japan had in the ring, and that was on its way out with all the other road-going twostrokes. Except for a few nice Italian exceptions, the 750 Performance Society appeared to be going on hard times.

In 1976 Suzuki gave the 750 fourstrokes a new shot in the arm with the introduction of the light and quick GS750, a bike that combined handling and race-winning performance with the accepted tradition of 750 utility. By 1979 Honda finally gave up the cosmetic and mechanical updating of the original CB750 series, unveiling an all new CB750F with a dohc engine, longer chassis and glossy modern styling. Suzuki redesigned its GS with a new frame and 16valve engine and Kawasaki countered the following year by boring out its successful KZ650 and turning it into a fast, fine handling 750. And this year Yamaha joined the fray, enlarging its 650 Maxim profiler into a shaft drive sport bike with a heavy overlay of technical dazzle and trickery.

Where high performance Japanese four-strokes are concerned, the hard times are now officially over.

In fact the standards of handling, durability and speed among the 750s produced by the Big Four are now known to be similar enough that there was a halfhumorous suggestion that any comparison among them might be inconclusive. After all, each has a high-revving dohc inline four-cylinder engine, double front discs, air forks, five-speed transmission, two wheels, etc., and each manufacturer keeps pretty close tabs on the competition, taking care not to be grossly outdone in some aspect of performance. What if we had all the makings of a clone contest? A test whose conclusion required only that you pick your favorite color?

As we’ll see, it didn’t turn out that way. Many weeks of commuting and weekend rides on all kinds of roads, a day of track testing at Willow Springs, another day at the drag strip, plus the usual brake and computer roll-on tests, all produced the hard numbers and distinct opinions that cause people to choose different motorcycles for different purposes. Personalities, faults, virtues and quirks surfaced during the test, making the side-by-side comparison all the more vivid.

THE BIKES

HONDA CB750F

Since its 1979 introduction the Honda 750F has received two model-year updates, most of the changes going into suspension work. Except for some minor carb modifications, the engine is unchanged. With four valves per cylinder operated by dual overhead cams (like all the others), it was the first of the 16-valvers among the Japanese Fours. It has a 9:1 compression ratio, a square 62 x 62mm bore and stroke configuration and a plain bearing crank. The valves are adjusted by shims that ride on top of the valve buckets and the engine is fed by four 30mm Keihin carbs with an accelerator pump.

Early models had plastic swing arm bushings, replaced in 1980 by needle bearings, and this year further chassis improvements include larger forks with improved bushings and air caps, new rear shocks, double-cylinder brake calipers front and rear and redesigned brake rotors and master cylinders. The rear shocks have adjustable compression and rebound damping; compression damping is set with a two-way lever at the bottom of the shock and rebound adjusted by a collar at the top, which must be rotated with a shock tool.

At 60.5 in. the Honda has the longest wheelbase by a small margin (the Suzuki is second at 60.25 in.) and has the feel and proportions of a long bike, with characteristically slow steering. The saddle, tailpiece, tank and sidecovers are styled in a sweeping, unified look reminiscent of Honda’s endurance racers. >

KAWASAKI KZ750

Kawasaki heralded the introduction of its KZ650 by advertising that it would blow any existing 750 into the weeds. It would have, too, but for the untimely arrival of a bunch of fast new 750s from its competitors, which kept the promise from being fulfilled. But Kawasaki has since gained the upper hand by boring out its 650 into a 750, redesigning the chassis a bit and releasing a 750 that, if it doesn’t actually blow the competition into the weeds, is at least marginally quicker than the others.

The KZ750 is actually a 738, out of respect for the limits of 650 overbore, and has a bore and stroke of 66 x 54mm. The double overhead cams act on valve buckets (two per cylinder) with small adjusting shims beneath them, necessitating cam removal for valve adjustment. A unique feature of the KZ engine is its Clean Air System which solves emissions problems by drawing fresh air into the exhaust ports through reed valves in the cam cover for more complete combustion. This simple system allows the Kawasaki to use accurately jetted and responsive 34mm Keihin carbs.

At 491 lb. with half a tank of gas the KZ gets the group lightness award, some 12 lb. lighter than the Seca, 53 less than the Honda and 59 lb. below the Suzuki. In dimensions it is closest to the Yamaha, with a 57.25 in. wheelbase and 31.5 in. seat height, giving it a lower, more compact feel and appearance than either the Honda or Suzuki. Overall, the KZ is the most basic of the four bikes. The eightvalve, alternator-on-crank engine, simple instrumentation and lack of padding and styling flourishes, all work to keep its weight and size to a minimum.

SUZUKI GS750

Suzuki’s GS750 was completely redone in 1980, with a plain bearing rather than roller crank, a 16-valve head, a longer wheelbase and more weight and comfort. The four-valve per cylinder head uses Suzuki’s Twin Swirl Combustion Chambers with two domes cut into the combustion chamber, effecting a separate swirl of intake charge from each valve for better combustion and anti-detonation characteristics. The GS has the only engine where valves are not adjusted with shims; instead, a single cam lobe operates a set of forked fingers which act on the valve stems with traditional screw-and-locknut adjusters.

Suspension last year was a bit on the wallowy but comfortable side, but for 1981 Suzuki has added leading axle air forks so a wider range of adjustment is possible. Rear shocks provide four-way adjustable damping and roller bearings are now used in the steering head. Though not as all-telling as the Yamaha’s, instrumentation is fairly complete on the GS with a fuel gauge and gear position indicator added to the usual faces and dials.

The Suzuki is the heaviest, longest overall and widest at the handlebars and it also has the largest, best padded seat. The engine is geared higher than any of the others, turning only 4328 rpm at 60 mph. Like the Honda, Suzuki’s GS is a long, large bike nearly identical in size and weight to a sister model higher up on the cc scale. In the Honda’s case that bike is the CB900F, and for the Suzuki it’s the GS1100. The GS1100 weighs only 7 lb. more and has an 0.25 in. longer wheelbase (virtually identical, given chain wear and adjustment) than the 750. The Kawasaki and Yamaha, on the other hand, are both developed from smaller bikes, the KZ650 and the Maxim 1, so the Honda and Suzuki both feel taller and longer by comparison. In the way of extremes for the group, the Suzuki has the largest swept area for brakes—260 sq. in.—and the best ratio of swept area to weight. >

YAMAHA 750 SECA

The most recent addition to the 750 sport class is Yamaha’s Seca, named after the Laguna Seca roadracing circuit. It is the only shaft drive bike in the group, showing its 650 Maxim 1 heritage, and it has an engine that in width looks more like a Twin or a Triple. Measuring only 18 in. from case cover to case cover, the engine has its chain-driven alternator positioned behind the cylinders to keep width to a minimum. The head uses two valves per cylinder with spark plugs positioned in the side of the domed combustion chambers, and the intake tract features Yamaha’s patented YICS (Yamaha Induction Control System) which is a sort of holding manifold cast into the head to distribute the intake charges more evenly.

Beyond the fairly sophisticated engine design, Yamaha has used the Seca as a sort of techno-demonstrator on which to hang all the electronic and suspension wizardry at its disposal. The instrument panel features a liquid crystal display (LCD) that monitors the condition or position or level of oil, battery, sidestand, lights, fuel, brake fluid and battery water. If something is amiss in one of these areas a flashing light comes on and tells you so. The checklist is run through automatically each time the engine is started, or on command of a button. Another button reduces the flashing warning light to a constant glow and, with a second push, makes it go away. The same system kills the engine if you try to ride away with the sidestand down.

Another interesting bit of work is the anti-dive front suspension. It uses brake fluid pressure to restrict oil flow through the damping holes and has a blow-off valve to allow suspension movement if you hit a sudden hard bump while braking. The forks still compress somewhat under braking, but the tendency is much reduced and softer springs can be used for normal riding without the drawback of excessive dive. The forks also have air caps so they can be adjusted for riding comfort. The electronics, anti-dive and shaft drive all make the Seca the most unusual and different bike in the group.

Even with all the features, plus a set of fully padded handlebars, it still manages to be relatively light, at 503 lb. only 12 lb. heavier than the Kawasaki. It also has the highest load capacity of the four, at 497 lb., and in wheelbase, length and seat height is nearly identical to the Kawasaki’s. With a list price of $3199, it is the most expensive of the group.

PERFORMANCE

When the Honda, Suzuki, and Kawasaki were introduced, in that order, each was the fastest 750 around, the new Class King. The newest of the four, the Seca was about a tenth of a sec. off the class record when we tested it in June, ’81, but coming on the heels of the KZ it also had the toughest act to follow. Running all of the bikes on the same day generally confirmed the previous order of performance, though all the bikes were slightly off their past marks because of the hot, dry weather on test day.

The Kawasaki KZ750 was the quickest 'and fastest of the four, turning a quarter mile of 1 2.39 sec. at 106.88 mph. We made half a dozen runs with the bike and every one of them came in under the best time of any other bike. In top gear roll-ons the KZ was fastest from 60-80 mph also, pulling it off in 5.3 sec. Only the Seca was quicker from 40-60 mph in top gear, by a tenth of a second. The KZ’s top speed with a half-mile run was 122 mph, same as the Seca’s. The Kawasaki’s drag strip performance meshes logically with its record in 750 Box Stock road racing where it is a consistent winner. Few Box Stock competitors waste time campaigning bikes that can’t win, and the KZ750 is presently considered to be the ‘'right tool for the job in 750. The bike has excellent mid-range and pulls harder coming off corners than most of its competition.

At Willow Springs Raceway, where we took our four bikes for a day of hard laps on the 2.5 mi. road course, the KZ also did well. All the test riders were able to get their best, consistent lap times riding the KZ, our resident club and endurance racer turning times in the mid 1:44s. On the track, the KZ is simply the most stable, confidence-inspiring bike to ride. It has good cornering clearance, does not wobble or shake its head over fast, bumpy sweepers, and has quick, responsive steering characteristics that make it a joy to guide through S-bends or tight corners. The bike has a tight, rugged, madeof-one-piece feel that everyone liked immediately.

The KZ’s only drawbacks on the track were its brakes and tires. On entering fast corners at the ends of straightaways the Kawasaki needed more lever pressure than any other bike and was also the hardest to modulate. As lever pressure increases the relationship between effort and stopping power becomes uncertain and there isn’t enough feedback to tell you whether or not the tire is about to lock. Several times riders backed off on the brakes and coasted wide through corners, finding themselves in too deep without enough brakes and not wanting to risk a lockup. Kawasaki advertises that its brake pads are especially good in the wet, so it may be that they have sacrificed a bit of dry performance under conditions as extreme as those on the race track. In any case, the KZ has the smallest brakes and least swept area in the group. The Honda has the same 3.1 lb./sq. in. brake loading, but the Honda’s brakes worked better and were easier to control. The KZ’s 142 ft. stopping distance from 60 mph was worst of group.

The Kawasaki’s F8 and K127 Dunlop tires felt overworked on the racetrack and our go-fast rider thought lap times would come down quite a bit with tires that felt as sticky as those on the Yamaha Seca. For fast street riding neither the tires nor the brakes are likely to cause serious problems, and the Kawasaki can be ridden fast and confidently with them. For fast acceleration, good mid-range, and excellent handling characteristics the high performance nod in the comparison has to go to the KZ.

A surprisingly short way off the Kawasaki’s pace as an all-around performer is the 750 Seca. The Seca was second fastest in the quarter mile with a 12.52 sec. at 106.25 run and had the same 122 mph in the half mile as the KZ. While it was just a tenth of a second slower from 60-80 mph, it was also one tenth quicker from 40-60.

On the race track the Seca is an excellent handler, despite the supposed non-sporting nature of the shaft drive. A small amount of rising and dropping of the rear end can be felt during abrupt throttle movement but once the rider grows accustomed to that, the Seca can be ridden hard without doing anything to upset the rider’s confidence. The anti-dive forks do a nice job of keeping the bike relatively flat and stable during hard braking. There’s nothing eerie or terribly unusual in the feel; the front end still compresses somewhat, but the movement is smoother and less abrupt than in other bikes. And the brakes are certainly capable of giving the anti-dive setup a workout. The Seca has a rear 7.9 in. drum brake, but the front discs are great big 1 1.6 in. units with an unusually high 226 sq. in. of front swept area. The master cylinder is operated via cable to the brake lever feel a bit vague at times, but the stopping power is excellent. During brake tests the Seca hauled down from 60 mph in 130 ft., better than anything else.

Good brakes and acceleration, along with an excellent set of tires, brought the Seca’s lap times right down amid those of the KZ. If the Kawasaki had better brakes and at least equally good tires, the Seca might be hard pressed to catch it, but in stock form (and this is a comparison of stock street bikes) the Seca can be made to cover 2.5 mi. of winding asphalt as quickly as the Kawasaki, our best lap times also in the mid-tohigh 1:44’s. Steering, like that of the KZ, is quick and accurate and the bike can be cornered hard with a minimum of unwanted chassis movement.

Picking a performance leader between the Suzuki and the Honda is difficult because the two are so close, but we had to give a slight edge to the Suzuki because of its better brakes, barely quicker quarter mi. and better manners on the racetrack.

The Suzuki turned the quarter mile in 12.45 sec. at 104.77 mph, a piddling 0.04 sec. quicker than the Honda, but 1.4 mph slower than the F in terminal speed. The GS’ top gear roll-ons were 0.1 sec. slower from 60-40 and 0.4 sec. faster from 40-60. Both of these, of course are only a tad (and a very small tad at that) off the Yamaha’s quarter mile figures. In other words, there isn’t enough difference here in performance to send a formerly-happy owner off to the trade-in store for a different brand. The Kawasaki is quickest. If any one of the other three is broken in properly and the rider didn’t have too much lunch, his bike is probably faster than the other two. And, make no mistake, they are all fast bikes.

Anyway. The Suzuki is a little quicker, but a little slower than the Honda in the quarter mile. The Suzuki's brakes are excellent, stopping the bike in only 132 ft. from 60 mph. Both the Honda and Suzuki have excellent brake feel while stopping hard with minimal lever pressure. The GS brakes have the most swept area of the lot at 260 sq. in. and also have the best ratio of swept area to weight, 2.7 lb./sq. in., and it shows when you have to haul the bike down quickly.

The GS750’s on-track handling manners might best be described as stable and elegant. It lacks the quick, raspy fighter plane feel of the Kawasaki and Yamaha and instead takes its corners in smoother, wider arcs. The long wheelbase and slow steering work together with the relatively soft suspension to deny the rider some of the feedback that comes through the handlebars on the other bikes. The GS is comfortable to ride, even on the racetrack, but feels a little vague during side-to-side cornering transitions and in fast, smooth sweepers when you are trying to get a feel for traction. But as the bike is pushed harder it soon becomes apparent the chassis and suspension can be relied upon not to do anything tricky, and then the GS can be ridden harder still, right up to the limits of cornering clearance. While the Yamaha and Kawasaki felt at home on the track almost immediately, the Suzuki demands a little more tentative track time to build up to a fast pace, then demonstrates that it handles very well after all.

BRAKING DISTANCE FROM 60 MPH

The Honda 750F, as mentioned, had the highest e.t. through the quarter mile by a very small margin, turning a 12.59 at 106.13, and 121 mph in the half mile. Typically for Honda the 750F makes most of its horsepower fairly high up on the tach face and likes to be revved if it is to keep up with the other 750s. This trait was noticeable at Willow Springs, particularly on a short uphill stretch that links turns three and four, where 3rd gear was just a little too high to pull the bike up into Corner Four as quickly as the other bikes, but 2nd gear was too low. For full power output the F works best when it’s kept spinning.

Like the Suzuki, the Honda has a long chassis and slow steering and works best if it is arced gracefully rather than darted into a corner. The Honda’s steering characteristics impart a reassuring feeling of calm control and directional stability when the bike is ridden around town or even at a fairly fast clip on winding public roads. On the track, however, that same stable, slow steering makes the bike a little harder to ride, requiring more effort and body English to heel it over into slow-to-medium-fast-corners. Where the bike should shine, but doesn’t, is holding a line through fast, wide open corners. Our test bike wobbled badly through Willow’s high speed Turn Eight, the rear tire wagging back and forth visibly whenever bumps were encountered or over small changes in pavement. We tried numerous changes in damping and preload and all combinations thereof without much effect. Two of the faster test riders attributed the problem to rear shocks and reported that after three laps of hard riding the rear shocks were gone away.

Which is a shame, because everything else on the Honda worked well. The new dual-piston brakes have a firm, positive feel at the lever and haul the bike down smartly from high speed with no unnecessary drama, though one rider complained that the big 11.5 in rear disc was almost too powerful and easy to lock up when the rear end got light. The new forks, with air pressure set at maximum recommended pressure, handle bumps well and still provide excellent road feel in cornering, and our test bike was the first 750F we’ve ridden with a good gearbox—no missed shifts or false neutrals during two days of abuse at the drag strip and race track. With a good set of aftermarket shocks and the right springs the Honda would probably find the race track a much happier place.

TOP GEAR ROLL-ON ACCELERATION,40-80 MPH

COMFORT & UTILITY

After a couple of all-day road trips everyone agreed, with no dissenting votes, that the Suzuki GS750 was the most comfortable of the four bikes. Its size worked to advantage here. Directional stability, compliant suspension, a very smooth running motor, and by far the best seat in the group ’made the GS the bike around which everyone hovered when a three hour ride was suggested.

The GS’ seat is both wider and better padded than any of the others and it is also the least radically stepped which means, happily, that you can slide your buns back a Tew inches when you get the urge without running smack into a high lip or the edge of the back seat. The handlebars on the GS are long and set at a slightly awkward angle, but the long tank and long seat at least allow you to choose your own distance from them.

The Suzuki has the highest gearing of the ^group, which drops it 150 to 250 rpm below the others at cruising speed in 5th gear. Turning 4328 rpm at 60 mph it isn’t exactly loafing along in the Harley tradition, but the high gearing and exceptionally smoothrunning motor make engine sound and vibration relaxed and unobtrusive out on the road. With the fuel capacity 5 gal. and a 52 mpg average on our test loop, distance 'between gas stations is in the 200-250 mi. range, and riding all that way without getting off is easy and comfortable on the Suzuki.

The GS was probably the least enjoyable bike to take on short jaunts or quick trips to the store because of its choke and carbure,tion. Like most Suzukis, full choke causes revs to soar painfully high when the engine is first started. No big thing, but you have to play with the knob until the engine settles down to an acceptable warm-up speed. The Suzuki was also the slowest to warm up and carbúrete well, feeling lean and hesitant until it was a few miles down the road. Once the engine is warm, carburetion is spot-on and crisp. A few years ago the Suzuki’s carb response would have been exemplary, but the other bikes in this group now have their choke circuits and jetting so well worked out, the GS’ small shortcomings are more noticeable.

Second runner up in the posh comfort category is the Honda. The 750F offers comfortable, compliant suspension and plenty of seat and elbow room out on the highway, but the seat itself is not as comfortable as the Suzuki’s. Designed to look more like a racing saddle, the Honda’s seat is rather narrow and the lack of side support on the legs begins to tell after a while. Footpegs also feel too far apart for the narrowness of the tank, so your knees are either out in open air or in a knock-kneed attitude against the tank most of the time. Despite that, the air-adjustable low-stiction front suspension and soft damping adjustments on the rear shocks and general roominess of the bike make it easy to live with on the road.

The Honda’s 5.3 gal. gas tank is the largest of the bunch and puts the bike into the same 200 mi.-plus range as the Suzuki. The fuel filler with a locking hinge over a screw cap looks racy but is more trouble than most to open and close. As long as the locking strap is hinged, why not just make the whole cap so it swings open? Hinged seats are nice too, and it would also be nicer on the Honda if you could swing the seat open and possibly use the empty tailpiece for carrying small articles, rather than having the seat bolted to the bike. It would also make tank removal easier for servicing.

All of the 750s tested have rear shocks with adjustable damping, and the Honda offers both compression and rebound adjustments. Compression changes are handled by a little two-way lever at the shock bottom, and rebound damping is changed—as it is on the other bikes—by a rotating collar at the top of the spring. The Honda, however, is the only bike where a tool is needed to rotate the collar. There is a hook-type shock tool in the kit for that purpose. The other bikes use some sort of knurled collar that can be rotated easily by hand, making the job a lot quicker and easier. But then the Honda’s rear shocks don’t work very well anyway, so those who replace them with aftermarket units won’t have to worry about the adjustment.

The Honda has a handlebar-mounted choke lever like the Suzuki’s, but fortunately you don’t have to play with it as much. It starts on full choke and warms up quickly, so it can be moved all the way off after a minute or two of running. When warm the engine accelerates smoothly without flat spots or hesitation.

The Kawasaki is so close to the Honda in the comfort ratings that some suggested it might even be rated ahead of it. How comfortable you find the Kawasaki probably depends on your size. The KZ’s seat is a little wider and flatter than the Honda’s and not quite as soft. The bars are a nice compromise between the tillers on the Honda and Suzuki and the flatter bars on some sport bikes, and their relationship to the seat and footpegs put most test riders in a comfortable seating position. The only drawback is that the KZ is a short bike with a stepped seat, so if you feel the need to stretch the only place to go is to perch yourself way up on the rear step and reach down for the bars, like a bear riding a tricycle. It looks ridiculous, but some of us gave in to it anyway on longer rides. On trips lasting less than an hour or so, however, even tall people can remain seated on the forward half and be comfortable enough.

For a short bike that should hobby-horse all over the place on bumpy roads, the KZ handles itself with unexpected grace. Closely spaced road seams are more intrusive than on the Honda or Suzuki, but the air forks and easy-adjusting damping collars on the rear shocks allow enough suspension latitude on the KZ that you don’t have to put up with a harsh ride.

With its Clean Air System the KZ is able to have reasonably rich carb jetting and still meet emission requirements, so it starts up and runs better during its first few minutes of operation than any of the others. The choke lever, mounted on the carbs as in days of yore, is needed only to get the engine running. After that it can be switched off entirely and the bike ridden away. This pleasant condition, along with the KZ’s compact size makes it a wonderful bike for running around town and quick trips to the store.

That carb-mounted choke lever is also symbolic of another virtue in the bike; its simplicity. A small lever instead of cables, knobs and associated parts makes the bike just that much simpler and lighter with fewer parts to break, buy or backorder. A choke lever doesn’t sound like much in itself, but when that simple-is-beautiful philosophy is applied all over the bike you get a nice clean motorcycle that doesn’t weigh as much as the others. Weight is important in motorcycles; you can feel it, and you can feel it when it’s missing. In the Kawasaki it’s missing and it feels good. It’s part of the reason the bike is fun to ride and goes faster than the others.

As another nice touch, both the seat and > the gas cap are hinged. Hooray. The gas tank holds 4.6 gal. and our average fuel mileage was 45 mpg, so gas stations will be welcome somewhere between 150 and 200 mi.

QUARTER MILE ACCELERATION

The KZ’s gearbox is a delight to use and has the most succinct, positive feel of the group. It shifts quickly and never leaves any doubt that you have successfully made it into the next gear.

The Kawasaki puts out such a low, throaty exhaust note and growls so agreeably going up through the gears that you expect it to vibrate or buzz more than it does. In fact, the bike is commendably smooth at all road speeds and has less handlebar tingle at cruising speeds than the Honda 750F. Of course none of the bikes tested here vibrates enough to raise any eyebrows of concern or drive customers away. Engine balance and mounting have been well worked out on all four, and in terms of engine vibration as it was understood in the Sixties, for instance, they simply don’t have any.

The Yamaha Seca came in last in our comfort rating, mainly because of its choppy ride on the highway. On freeway seams or any other closely spaced road bumps the Seca pitches up and down and pounds the rider until he wants to cry uncle, or something less printable. Air and damping adjustments help a little, but not enough. Beyond that the sling-like seat, which is nicely padded, is simply too restrictive for real comfort. Where you are sitting feels pretty good for quite a while, but that’s all there is. No moving around to rest weight on a different part of your tailbone. The handlebars and footpegs are well placed, however, relative to the seat. Both the Kawasaki and Yamaha have seat heights of 31.5 in., which is low enough for shorter riders to stop comfortably in a both-feet-onthe-ground attitude.

Maintenance chores on the Seca will be eased somewhat with no chain to lube, and the battery and electrics are easy to get to beneath the hinged seat. In fact maintenance is further simplified because the LCD monitor is there on the instrument pod to tell you if anything on the bike needs attention. Nearly all of the normal service areas are covered; lights, battery, oil and fuel. And if the LCD monitor itself needs attention you’ll know because no warning lights or messages will appear when you start the bike. Like the Maxim 1, the Seca carries its own security lock and chain, folded into a compartment beneath the left sidecover.

Also on the unusual list is a second, smaller rectangular headlight below the main headlight. On our first Seca test bike in June, 1981, this light was tinted yellow—a fog light. It now has a clear lens and functions only as an auxuliary driving light. The Seca is also the only bike with self-cancelling turn signals, which can be switched off by pushing in on the button rather than centering the switch, and a thumb-operated

choke lever at the left handlebar and fully padded handlebars. Yes, padded.

The amazing thing about the Seca is that even with all these novel add-ons it doesn’t weigh any more than it does. Its 503 lb. weight makes it second lightest, 12 lb. heavier than the Kawasaki but 40-50 lb. lighter than the Honda and Suzuki. Low weight, small overall size and low seat make it an around town errand-running equal to the Kawasaki. It’s a fun, spirited bike for zapping around on short trips, especially if there are curves in the way.

The Seca starts instantly on full choke and can be ridden away after a short warmup. The choke can be slowly pushed into the' off position with the left thumb as you ride, but quick stops will kill the engine any time the choke is still on. Shifting action is good though not quite as crisp and mechanical as the Kawasaki’s, and the engine revs with quick, turbine-like whoops and a subdued but pleasantly brash exhaust note. The engine is smooth all the way through the rev range, with just a hint of buzziness on the highway.

TEST WEIGHT, HALF-TANK OF FUEL

CONCLUSION

Throughout the test people would see the four bikes together at a gas station or restaurant, gather what we were doing, and ask with a confidential wink, “Well, which one’s gonna win?”

To which the answer would have to be, “That depends on what you want to do with your motorcycle.” And to a lesser extent it also depends on your own concept of what a motorcycle should be and how it should look. It’s probably easier and more exciting to do a comparison of any kind when you have a couple of real losers, something mediocre to stick in the middle and a winner whose sheer competence outshines anything around it. Unfortunately, the four 750s weren’t so easy on us.

In performance, quarter mile times all ranged between 12.59 and 12.39 sec., a spread of two tenths of a second. Terminal speeds varied by only 2.1 mph, from 106.88 mph all the way down to 104.77 mph. All the bikes went through the half mile traps between 120 and 122 mph. Two fast, consistent riders on a 2.5 mi. road circuit managed to wring out a 2 sec. difference in lap times between the slowest and the fastest bikes, and the slowest had a valve that was looseningup and needed attention. Performance is no problem with any of the bikes.

Nevertheless, the Kawasaki KZ750 was quickest and fastest by a larger margin than separated the other bikes. On the track it turned in better lap times and produced those good times at a higher level of confidence and with less riding effort. That performance, along with its light weight, simplicity and rugged feel made it a favorite of three of the test riders. Most of the resistance to the Kawasaki was purely subjective; several people commented that the seat and tail piece made the bike look too short and chunky, breaking up the otherwise straightforward lines. In a game of Which Bike Would You Like to Keep For Your Own, those who picked the Kawasaki said they would probably install a different set of tires, try some different brake pads and reupholster the seat and then have a nearly perfect 750. Words like “honest” and “basic” and “feels like a motorcycle” circulated around the Kawasaki camp. It was the favorite of the roadracing contingent, and a staffer who now races a GPz550 liked the bike well enough to consider trading up to 750 Box Stock.

The popularity of the other three bikes varied according to styles of riding. A couple of the dirt-oriented guys who seldom tour but like to take fast weekend rides on canyons and mountain roads both picked the Seca as their favorite. They pointed out that the seat and suspension, while not ideal for long trips, posed no real problem on shorter rides, and liked the turbine-like responsiveness of the motor, quick, easy handling and the tight, unified feel of the chassis. Both thought the Seca was the best looking of the bikes. The Seca’s styling divided people most sharply. Those who didn’t care for the Yamaha said it was overstyled or “too futuristic” and were unimpressed by the gadgetry and flashing red lights, preferring the stark and simple approach. The public liked the Seca best; out on the streets it attracted more attention than any of the others.

Significantly, the Seca finally lays to rest the traditional belief that shaft drive bikes have to be inefficient, heavy and sub-par in handling. In race track performance it handled beautifully, second only to the KZ750, and not by much, and it weighs roughly 50 lb. less than the Honda or the Suzuki. When Yamaha decided to introduce a sport 750 with anti-dive forks, complex instrumentation and shaft drive their engineers knew they would be under pressure to make a bike that didn’t pay a penalty in weight and performance for being loaded with features. In that respect they succeeded in disarming the critics. Technipally and functionally the bike is an accomplishment; narrow, fast, fine handling and sophisticated. And it sounds good.

Whenever comfort or touring were mentioned the Suzuki GS surfaced as the obvious choice. The big comfortable seat and supple suspension both make it pleasant for longer trips. Good brakes, graceful handling and the ultra-smooth engine also drew praise. While no one was knocked out by the appearance of the GS, no one objected to it either. It was often described as handsome, understated or nice looking. The same traits that make the GS a good touring bike worked against it for some of the riders, a couple of whom thought it was simply too big, a feeling amplified by the large handlebars. One commented “it feels like a 1000 or an 1100 with a 750 engine in it.” The Suzuki came off with almost a sleeper image; it was listed more often than any of the others as a second favorite because of its usefulness. “If I really had to go somewhere instead of just going riding, I’d take the Suzuki,” was a typical comment. The Suzuki is also the group’s big bike alternative, as larger riders who felt cramped on the Yamaha and Kawasaki liked the Suzuki best; a favorite of the six-foot-and-over crowd. For everyone who rode it the GS handled passengers, rough road and long distances with the greatest ease. Except for the tall handlebars, high idle on choke and the relatively long warmup time, there were virtually no other complaints with the Suzuki or suggestions that anything else about it should be changed.

The Honda came out in an odd position in this comparison, that of the Great Middle Roader. It wasn’t the fastest, most comfortable, best handling, quickest stopping, smoothest, most traditional or most futuristic, yet it wasn’t too far off the mark in any of these categories. It had the greatest talent among all the bikes for cohering a lot of bases and not doing too badly at any of them. Its forte is balance; an all-rounder as the British would say. It’s a big enough bike to carry two people in reasonable comfort, but not as big and comfortable as the Suzuki. It has crisp, modern styling but is not as futuristic as the Seca. Instrumentation and controls are simple and basic, like the Kawasaki’s, but it’s a sleeker, more currentlooking machine than the Kawasaki. It’s longer and slower steering than the Kawasaki or Yamaha, but doesn’t feel as large and heavy as the Suzuki. The high speed handling problems which surfaced on the race track will go largely unnoticed in street riding and, in any case, can probably be cured with better rear shocks. (One test rider said he liked the appearance of the Honda so much better than any of the others he would change the shocks or whatever else it needed, just to have it in his garage to look at. Nearly everyone agreed it was a good looking machine, combining many of the nicest design elements of the others.)

In other words, the Honda’s strong suit is versatility. Without being very specialized or having one really endearing functional trait, it manages to do a lot of different jobs fairly well. If performance buffs go after the Kawasaki and long-distance types buy the Suzuki and technology and styling aficionados gather around the Yamaha, then> the Honda will probably draw a certain number of buyers from all those groups. Not that the other bikes are terribly specialized or exclusive in their usefulness; the Honda is merely less so by the slightest margin.

FUEL CONSUMPTION

It was those slight margins that separated the four 750s all through the comparison. If the test had been a foot race with four athletes out on a cinder track, it would have been one of those photo finishes where the winning runner breaks the string by taking a deep breath and throwing himself forward at the last minute. The crowd, of course, wouldn’t know who won until the photo was developed. But even in close races people pick favorites, often for very subjective reasons. And this was one race

where you could afford to be subjective and not go very far wrong.

As mentioned before, it’s far easier to do this sort of thing when the group produces a glorious winner and a hopeless loser, with lots of latitude between. But in this test there was no pariah of the class, no bike with its tank dented by 10-ft. poles, nor was there a clear and shining class hero. When the test was over all the riders were asked individually, “If you could keep one of the 750s for your very own, which one would you take home tonight?’’ No one flashed out with a quick answer. People put their hands behind their heads, stared at the ceiling, hemmed, hawed, thought out loud, mumbled justifications for this bike or that, made up their minds, then in some cases

changed their minds. It was a tough one.

If forced to either pick a winner or give up riding motorcycles, there is one of the four that was mentioned most often. That was the Kawasaki. Its slight performance advantage and light weight don’t tip the scales, but at least nudge the needle a little.

So what we tried to do with the test was delineate the character of each bike clearly enough for people to decide which bike might suit them best. To go overboard in condemning or praising one or more of these bikes at the expense of the others would be doing potential buyers a disservice. They are all fast, well-built, reliable and exciting machines. The Official High Performance 750cc Motorcycle Admiration Society never had it so good. E9

SPECIFICATIONS

Honda

CB750F

$2998

Kawasaki

KZ750

$2899

Suzuki

GS750EX

$2999

Yamaha

750 Seca

$3199

View Full Issue

View Full Issue