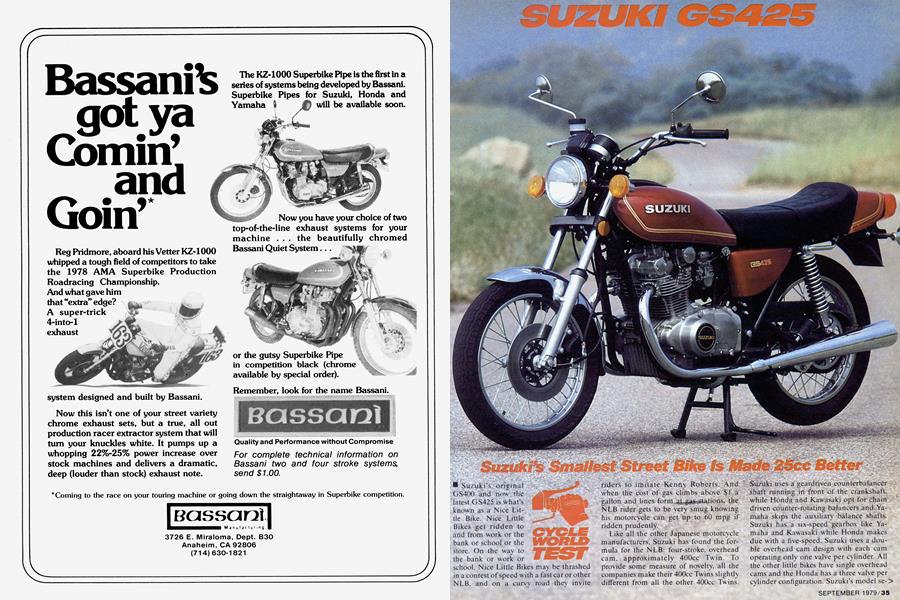

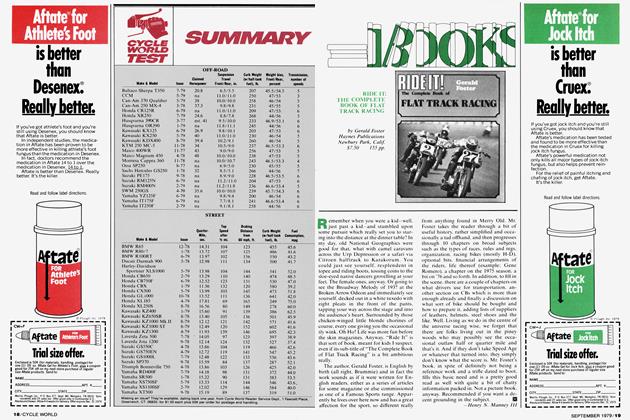

SUZUKI GS425

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Suzuki's Smallest Street Bike Is Made 25cc Better

Suzuki’s original GS400 and now the latest GS425 is what’s known as a Nice Little Bike. Nice Little Bikes get ridden to and from work or the bank or school or the store. On the way to the bank or work or school, Nice Little Bikes may be thrashed in a contest of speed with a fast car or other NLB, and on a curvy road they invite riders to imitate Kenny Roberts. And when the cost of gas climbs above $1 a gallon and lines form at gas stations, the NLB rider gets to be very smug knowing his motorcycle can get up to 60 mpg if ridden prudently.

Like all the other Japanese motorcycle manufacturers, Suzuki has found the formula for the NLB: four-stroke, overhead cam, approximately 400cc Twin. To provide some measure of novelty, all the companies make their 400cc Twins slightly different from all the other 400cc Twins.

Suzuki uses a geardriven counterbalancer shaft running in front of the crankshaft, while Honda and Kawasaki opt for chain driven counter-rotating balancers and Yamaha skips the auxiliary balance shafts. Suzuki has a six-speed gearbox like Yamaha and Kawasaki while Honda makes due with a five-speed. Suzuki uses a double overhead cam design with each cam operating only one valve per cylinder. All the other little bikes have single overhead cams and the Honda has a three valve per cylinder configuration. Suzuki’s model se-> lection is similar to the competition. There’s the base model 425 tested, a luxury GS425E that has cast wheels and a stepped seat and there’s the GS425L, or LowSlinger, with semi-chopper styling.

The biggest difference between the Suzuki and its competition is the addition of 25cc to the engine this year, done by using 2mm larger diameter pistons, 67mm instead of 65mm. On the 400cc Suzuki the pistons were the same size as those of the GS750. Now the GS425 pistons are between the 67mm pistons of the 750 and the 69mm pistons of the GS850, which should offer lots of alternatives for big bore tinkering.

Twenty-five cubic centimeters isn't a huge difference on a 400cc-class machine, but the difference is more noticeable than it would be on a thousand, for instance. There may be an additional two horsepower in those 25cc; there’s also more torque.

Aside from the larger pistons and revised weight of the gear-driven counterbalancer to compensate for the pistons, the GS425 is little changed from the GS400. There’s the same sturdy and stable double downtube cradle frame, same single front disc and rear drum brake, same suspension and same clean and simple styling.

In a fiercely competitive class of motorcycles, the GS425 is the entry with the most marketable features. What other 400class bike has dual overhead cams, automatic cam chain adjuster, digital gear readout, six-speed transmission, disc front brake, electric starter, gear-driven counterbalancer shaft, roller bearing crankshaft, and constant vacuum carburetors? Whether any or all of these so-called features are needed or even worthwhile on this motorcycle can be debated.

In selected applications, each of the GS425’s features really are Good Things. Dual overhead cams can operate valves directly, keeping the valve train light for high revs. Six-speed transmissions can help keep a cammy engine in the powerband. Roller bearing crankshafts may offer slight advantages for extremely high speed engines, and constant vacuum carbs can keep an over-carburetored engine from bogging.

The 425 Suzuki probably doesn’t need a six-speed, or dual cams or roller bearings on the crank. It doesn’t run that fast and simpler designs can work perfectly fine. But the Suzuki has a long list of pieces presumed to be good and the motorcycle itself works very well indeed and the price is in line with the competition so who cares if it isn’t any faster than it would be with a five-speed?

Being patterned after the larger Suzuki Fours, at least in the top end, means parts like the cam chain tensioner, piston pins, cam followers, adjusting shims and numerous bits and pieces are interchangeable even if the piston size is different this year.

Riding the Suzuki Twin could hardly be easier. Of course the clutch lever interlock requires a rider to hold in the clutch before the electric starter will turn over the engine. And the choke lever mounted on the lefthand Mikuni is touchy, inviting a rider to tamper with the interlock so he can fiddle with the choke lever while trying to start the bike.

Once the engine fires it will idle at about 4000 rpm with full choke. There’s no partial choke position on the choke lever and it takes a couple of miles of riding before the Suzuki will run without the choke on.

Riding through town the engine feels larger than a 400 or even a 425. There’s more low-end torque than any of the other 400-class four-strokes, enough so the Suzuki can be run around town in fifth and even sixth gear. From 6000 rpm the power is surprising for a 425. Clutch pull is light and the clutch is positive. Throttle response is instantaneous. Too instantaneous. Tiny changes in throttle position are translated into the engine either pulling or slowing down and keeping a steady pace at slow speeds is difficult because of the twitchy response of the CV carbs.

On the highway the GS425 is so smooth it doesn’t feel like a Twin. Below 3000 rpm the uneven firing intervals from the 180° crank can be felt as a throbbing when the power is on, but above 3000 rpm the impulses blur and the counterbalancers work and there’s no more vibration than most Fours have. Compared to the other 400s, the Honda spins faster at highway speed and feels busier, though it’s just as smooth as the Suzuki while the Kawasaki is rougher and the Yamaha doesn’t have any counterbalancer shaft and is noticeably rougher.

Suzuki jumped into the lead in suspension development when the GS750 was introduced and widened the gap between itself and the other Japanese manufacturers with the GSlOOO’s air/coil front forks and adjustable damping rear shocks. On the GS425, however, the suspension is only normal. There’s about 5 in. of travel in front and a little less than 4 in. in back. Spring rates are a bit firm for one rider and a bit soft for two riders. Damping is adequate to control the 399 lb. bike in swift riding, but on freeway expansion joints the machine bounces. So while the GS425 suspension isn’t as harsh as the Kawasaki KZ400’s suspension, for instance, it isn’t any better than the suspension on the Yamaha XS400 or Honda Hawk.

Handling is competent. There are no surprises, no real flaws. Being relatively light and small, the GS425 responds quickly and with little effort. It’s not as flighty as the Yamaha RD400 or even the Yamaha XS400; it feels larger than the Yamahas and requires correspondingly larger movements to make it turn the same amount. Ground clearance is certainly adequate for normal riding, while the canyon racers will find the centerstand scrapes on hard lefthand turns and the folding footpeg (new' this year on all Suzukis) w ill

contact first on righthanders. The limits of cornering clearance are about the same as the tire’s limits and scraping the pegs on less-than-perfect surfaces means the rear end will be sliding slightly at the same time. All controllable and all in good fun.

As a commuter scooter the Suzuki Twin has few' shortcomings. The sudden throttle response is the most noticeable flaw. Oth-

ers are tiny matters such as the lack of an ignition switch mounted steering lock. We’d gladly trade the locking cover over the gas cap for a fork lock integrated with the ignition. But then we don’t much care for the cover over the gas cap. The locking cap used on the GSIOOO is a far better solution.

Controls on the Suzuki are first rate. Non-self-cancelling signals are easy to reach, the horn and starter buttons are handy (but the horn should be louder), brake and clutch levers are close enough and require little muscle power. The handlebars on the 425 are narrower than the larger Suzuki bars, don’t bend back as much and proved more popular with every test rider than the bars on the larger Suzukis. Contrary to modern fashion, the seat on the base model 425 isn’t stepped and it was fine for normal use. Instruments are easy to read, even the digital gear readout. This year Suzuki has started using individual bulbs to illuminate the readout instead of the light emitting diodes. The result is a brighter, more easily read display and less expensive light replacement. On a motorcycle that even includes the gear readout it’s surprising not to find an oil pressure warning light, though.

Braking power is a match for the speeu potential of the GS425, though the rear brake is a bit touchy. The single front disc is powerful, easy to control, and doesn’t fade. The rear brake can lock more easily than it should but it’s plenty powerful for the size of the Suzuki.

One almost-shortcoming of many commuter bikes is gas mileage. Big bikes get between 40 and 50 mpg in normal use and have gas tanks large enough so they can go 200 mi. between fill-ups. But the 400s—all of them —don’t get appreciably better mileage than bikes twice their size. The 425 got 52 mpg in the 100 mi. CW mileage loop, not a bad performance, but not exceptional either. Out on a weekend photo shoot and accompanying a Yamaha 750 and a Suzuki 1000, the Suzuki was getting 54 mpg. the Yamaha 50 mpg and the 1000 got 48 mpg. But because of the 3.7 gal. gas tank the Suzuki 425 had the shortest range of the three bikes. There’s room for improvement here.

Overall the Suzuki stacks up well against the competition. It’s at least as fast or faster than the other 400cc four-strokes, has noticeably more low-end torque so it feels faster, is an excellent handling motorcycle. easy to ride and convenient to use.

Everyone w ho rode the Suzuki made the same sort of comments: Nice little bike, perfect manners, no flaws, yet after 10 minutes you feel you have plumbed its depths.

If there’s little to say about the 425, it’s because there is little to criticize. A Nice Little Bike. S3

SUZUKI GS425

$1589