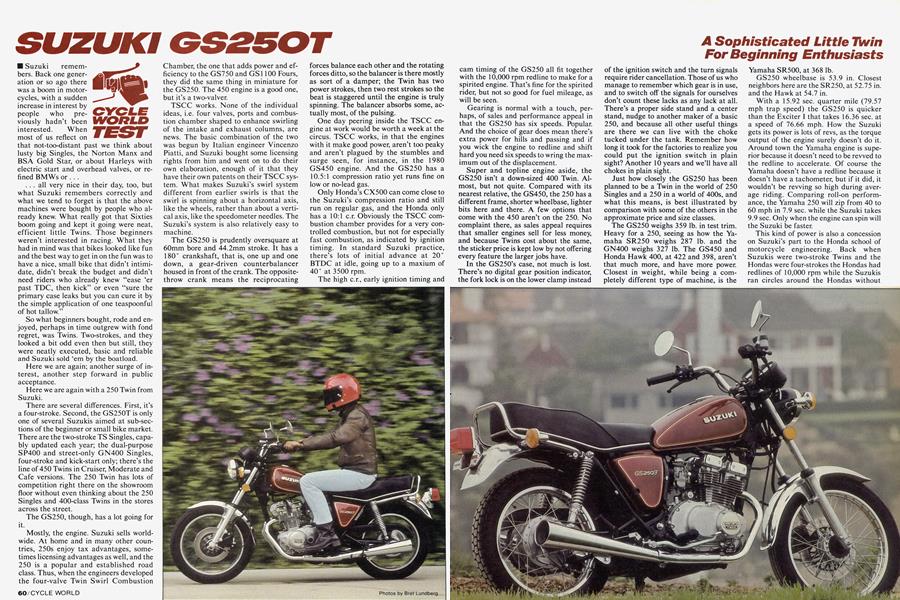

SUZUKI GS250T

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Suzuki remembers. Back one generation or so ago there was a boom in motorcycles, with a sudden increase in interest by people who previously hadn’t been interested. When most of us reflect on

that not-too-distant past we think about lusty big Singles, the Norton Manx and BSA Gold Star, or about Harleys with electric start and overhead valves, or refined BMWs or...

...all very nice in their day, too, but what Suzuki remembers correctly and what we tend to forget is that the above machines were bought by people who already knew. What really got that Sixties boom going and kept it going were neat, efficient little Twins. Those beginners weren’t interested in racing. What they had in mind was that bikes looked like fun and the best way to get in on the fun was to have a nice, small bike that didn’t intimidate, didn’t break the budget and didn’t need riders who already knew “ease ‘er past TDC, then kick” or even “sure the primary case leaks but you can cure it by the simple application of one teaspoonful of hot tallow.”

So what beginners bought, rode and enjoyed, perhaps in time outgrew with fond regret, was Twins. Two-strokes, and they looked a bit odd even then but still, they were neatly executed, basic and reliable and Suzuki sold 'em by the boatload.

Here we are again; another surge of interest, another step forward in public acceptance.

Here we are again with a 250 Twin from Suzuki.

There are several differences. First, it’s a four-stroke. Second, the GS250T is only one of several Suzukis aimed at sub-sections of the beginner or small bike market. There are the two-stroke TS Singles, capably updated each year; the dual-purpose SP400 and street-only GN400 Singles, four-stroke and kick-start only; there’s the line of 450 Twins in Cruiser, Moderate and Cafe versions. The 250 Twin has lots of competition right there on the showroom floor without even thinking about the 250 Singles and 400-class Twins in the stores across the street.

The GS250, though, has a lot going for it.

Mostly, the engine. Suzuki sells worldwide. At home and in many other countries, 250s enjoy tax advantages, sometimes licensing advantages as well, and the 250 is a popular and established road class. Thus, when the engineers developed the four-valve Twin Swirl Combustion Chamber, the one that adds power and efficiency to the GS750 and GS1100 Fours, they did the same thing in miniature for the GS250. The 450 engine is a good one, but it’s a two-valver.

TSCC works. None of the individual ideas, i.e. four valves, ports and combustion chamber shaped to enhance swirling of the intake and exhaust columns, are news. The basic combination of the two was begun by Italian engineer Vincenzo Piatti, and Suzuki bought some licensing rights from him and went on to do their own elaboration, enough of it that they have their own patents on their TSCC system. What makes Suzuki’s swirl system different from earlier swirls is that the swirl is spinning about a horizontal axis, like the wheels, rather than about a vertical axis, like the speedometer needles. The Suzuki’s system is also relatively easy to machine.

The GS250 is prudently oversquare at 60mm bore and 44.2mm stroke. It has a 180° crankshaft, that is, one up and one down, a gear-driven counterbalancer housed in front of the crank. The oppositethrow crank means the reciprocating forces balance each other and the rotating forces ditto, so the balancer is there mostly as sort of a damper; the Twin has two power strokes, then two rest strokes so the beat is staggered until the engine is truly spinning. The balancer absorbs some, actually most, of the pulsing.

One day peering inside the TSCC engine at work would be worth a week at the circus. TSCC works, in that the engines with it make good power, aren’t too peaky and aren’t plagued by the stumbles and surge seen, for instance, in the 1980 GS450 engine. And the GS250 has a 10.5:1 compression ratio yet runs fine on low or no-lead gas.

Only Honda’s CX500 can come close to the Suzuki’s compression ratio and still run on regular gas, and the Honda only has a 10:1 c.r. Obviously the TSCC combustion chamber provides for a very controlled combustion, but not for especially fast combustion, as indicated by ignition timing. In standard Suzuki practice, there’s lots of initial advance at 20° BTDC at idle, going up to a maxium of 40° at 3500 rpm.

The high c.r., early ignition timing and cam timing of the GS250 all fit together with the 10,000 rpm redline to make for a spirited engine. That’s fine for the spirited rider, but not so good for fuel mileage, as will be seen.

A Sophisticated Little Twin For Beginning Enthusiasts

Gearing is normal with a touch, perhaps, of sales and performance appeal in that the GS250 has six speeds. Popular. And the choice of gear does mean there’s extra power for hills and passing and if you wick the engine to redline and shift hard you need six speeds to wring the maximum out of the displacement.

Super and topline engine aside, the GS250 isn’t a down-sized 400 Twin. Almost, but not quite. Compared with its nearest relative, the GS450, the 250 has a different frame, shorter wheelbase, lighter bits here and there. A few options that come with the 450 aren’t on the 250. No complaint there, as sales appeal requires that smaller engines sell for less money, and because Twins cost about the same, the sticker price is kept low by not offering every feature the larger jobs have.

In the GS250’s case, not much is lost. There’s no digital gear position indicator, the fork lock is on the lower clamp instead of the ignition switch and the turn signals require rider cancellation. Those of us who manage to remember which gear is in use, and to switch off the signals for ourselves don’t count these lacks as any lack at all. There’s a proper side stand and a center stand, nudge to another maker of a basic 250, and because all other useful things are there we can live with the choke tucked under the tank. Remember how long it took for the factories to realize you could put the ignition switch in plain sight? Another 10 years and we’ll have all chokes in plain sight.

Just how closely the GS250 has been planned to be a Twin in the world of 250 Singles and a 250 in a world of 400s, and what this means, is best illustrated by comparison with some of the others in the approximate price and size classes.

The GS250 weighs 359 lb. in test trim. Heavy for a 250, seeing as how the Yamaha SR250 weighs 287 lb. and the GN400 weighs 327 lb. The GS450 and Honda Hawk 400, at 422 and 398, aren’t that much more, and have more power. Closest in weight, while being a completely different type of machine, is the Yamaha SR500, at 368 lb.

GS250 wheelbase is 53.9 in. Closest neighbors here are the SR250, at 52.75 in. and the Hawk at 54.7 in.

With a 15.92 sec. quarter mile (79.57 mph trap speed) the GS250 is quicker than the Exciter I that takes 16.36 sec. at a speed of 76.66 mph. How the Suzuki gets its power is lots of revs, as the torque output of the engine surely doesn’t do it. Around town the Yamaha engine is superior because it doesn’t need to be revved to the redline to accelerate. Of course the Yamaha doesn’t have a redline because it doesn’t have a tachometer, but if it did, it wouldn’t be revving so high during average riding. Comparing roll-on performance, the Yamaha 250 will zip from 40 to 60 mph in 7.9 sec. while the Suzuki takes 9.9 sec. Only when the engine can spin will the Suzuki be faster.

This kind of power is also a concession on Suzuki’s part to the Honda school of motorcycle engineering. Back when Suzukis were two-stroke Twins and the Hondas were four-strokes the Hondas had redlines of 10,000 rpm while the Suzukis ran circles around the Hondas without ever spinning more than, say, 8000 rpm. Note, too, that the original Suzuki X6 Hustler would turn a quarter mile in 15.3 sec. at 84 mph, noticeably quicker than this Suzuki 250 or any 250 of its day.

When dealing with perhaps the most discussed measure of performance in this class, miles per gallon, the GS250 is an economy bike. For the former car owner, 63 mpg will be a gift from above.

Then a check of the chart shows the GS450 at 64 mpg, the GN400 at 71, the SR250 at 76 and the SR500 at 62, all measured on the same 100-mi. loop. What happens here is that the other 250s are smaller and lighter, so they do less work, while the larger engines aren’t that much heavier and keep the same pace, running with the traffic in city and on the highway. Singles are more efficient than Twins and the other Twin on the list turns fewer revs per mile and works less hard. Fuel consumed is a function of work performed.

A test result we didn’t like to see at all was the braking distances. The GS250 has a front disc and rear drum, it’s light, well, lighter than bikes with larger engines.

But the stopping distances are more like those turned by a good big bike, longer than what you expect from a good small bike. The tires do it. Grip or step too hard and the tires slide. This isn’t the brakes, as muscular demand is linear and broad; the brakes can be controlled. But when you haul down hard, the tires aren’t up to the job. We can’t say it’s a safety hazard; the GS250 stops well within legal requirements and we didn’t meet any situation during a month and 1000 mi. that the brakes wouldn’t handle. But we do believe better tires would shorten the stopping distances. Lack of blazing power can be ridden around. There’s no such thing as surplus stopping power.

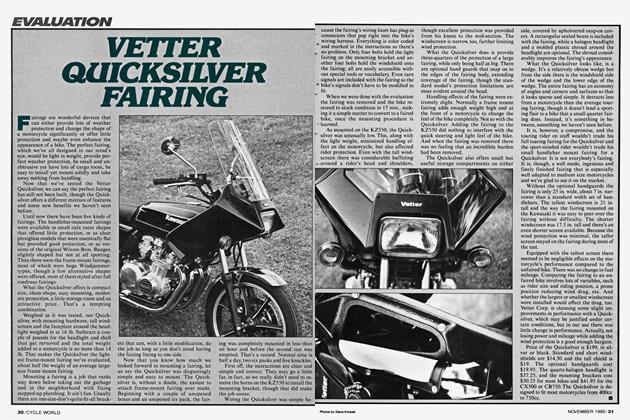

Styling of the GS250 is just about right. As in the days of the original small Twins, no attempt has been made to give the 250 outrageous looks. Instead the tank, mildly stepped seat and mildly high bars, the separate rear fender with grab handle, give a hint of the L-model Suzukis but not enough to threaten or interfere with the operation of the machine. Seat height is close to what average heights have been since the invention of rear suspension (extremists like Harley and Guzzi aside). The bars are the proper distance from the seat and riders of average height, say 5-foot-7 to 5-foot-ll, won’t find the mirrors filled with their knees.

Enough figures. The role best filled by the GS250 is that of Rush-Hour Rascal. Easy start, quick warmup. The GS balances well, the rider’s feet are close to the ground and all controls are pleasantly light. Broad clutch engagement and not too much torque at low revs means the bike can be moderated, nipped through openings, deftly squirted between trucks, slipped through gaps in the jam. It buzzes away from the lights.

Fun. Although it’s a bit much to say anybody ever headed for downtown at 4:30 p.m. just for the joy of skipping through the crush, getting home on time whilst all around you radiators boil and cage jockeys wish they’d never joined the rat race, still, when you are trapped in the sludge of city life, if you’re riding the GS250, you aren’t trapped, if that’s the right way to say it.

Ever see the old copcycle trick, where you come to a complete stop, feet up, then ride away? Ever wish you could do it? The GS250 is a great machine to practice with.

What the GS250 doesn’t do as well is sports and touring. Winding through the gears, there’s enough power. But although the engine is smooth and the shriek of the engine winds to a pitch so high it fades from the human ear, there isn’t a lot of hillclimb torque on the highway and the engine is turning 6500 rpm at an indicated 60 mph. It won’t hurt the engine but that is a lot of revs for coast-to-coast riding. Spring rates are relatively high and the short wheelbase makes for a pitching ride on the concrete slabs.

Sunday sports are hampered by the toohard tires and the enforced uprightness of the riding position, with low power another minus. Sightseeing, fine. A trip to the hiking trail, terrific. But for making time, zooming through the twisties, the GS250 rider who goes in company with, say, an XJ650 Yamaha and a Norton Commando will soon find himself wondering where the other guys went.

But then Sports and Touring usually come after the Thrifty Two-Fifty stage.

We club racers, jaded old guys and tentup tourers get requests on occasion that the smaller bikes be tested by people whose opinions are not yet cast in stone. This time, we had one, a new man in the parent company. He’s always been interested in motorcycles so when he found us he asked for advice. Easy, we said, enroll in the Motorcycle Safety Foundation-endorsed course at the local junior college. Get your license and then you can borrow all the keen machines in our shop.

We say this all the time. But this man did it. As a graduation present, he turned in a genuine test report on the GS250.

Fiddling with the choke, sidecover lock and locking gas cap was a bother, he reported. Riding in town was great, riding on the Interstate in a cross-wind, not so great. The riding position was fine, it doesn’t (Thank God) have that laid-back look and car drivers who run red lights can hear the bike’s horn.

“It’s clean, respectable and well mannered. Even before getting on this one, you wonder what it will deliver. Somehow it looks like it won’t disappoint you, even though it has skinny tires.

“I feel sorry for anybody who buys his first bike without trying this one.”

SUZUKI

GS250T

SPECIFICATIONS

$1349

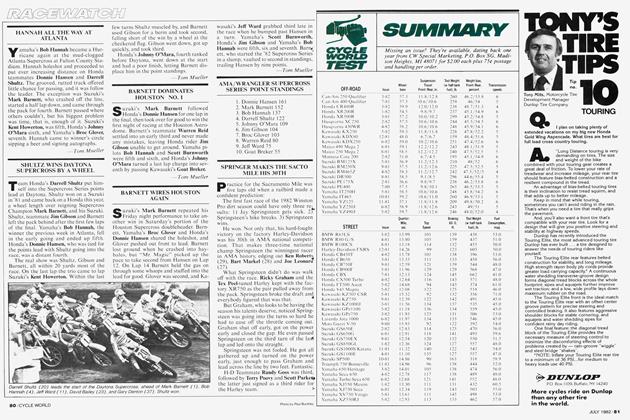

ACCELERATION

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue