UP FRONT

DEPARTMENTS

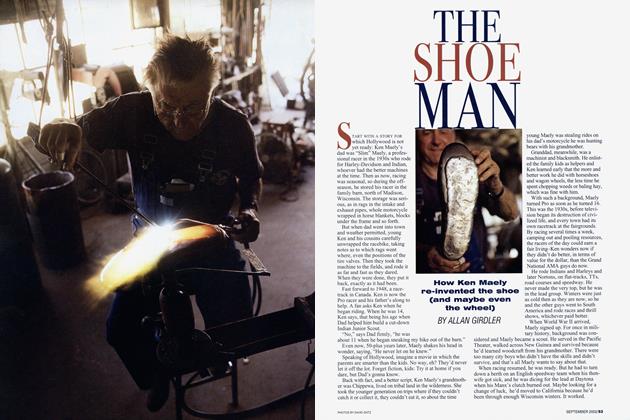

Allan Girdler

A SINGLE SUCCESS

Early on one frosty morning I was half-way up the hill from the ocean, running with the traffic, 6 thou showing on the tach, when I rolled off a fraction, looked around and thought “How things have changed.”

When I first began hanging around this magazine, back about the time Harley-Davidson invented the overhead valve, I knew from nothing about sophisticated motorcycles. Oh, I had read all about the multis, the big-buck tourers and full-race scramblers (that’s motocross to you kids) but I had never owned one, or even ridden one, my riding pals being more of the Harley or Triumph persuasion.

What I owned was one motorcycle, a humble dual-purpose 250 Single. Because I didn’t know' any better all the riding I did, I did on that bike. I rode it to work and back on the Interstate, I went cowtrailing, even rode a trials meet and when the weekend came I lashed a duffle bag across the rear fender and rode as far as daylight would take me.

My slogan—had I been aware enough to have had one—would have been Happiness Through Ignorance. Because I didn’t have a motorcycle that was supposed to do all these things, and didn’t know that I wasn’t supposed to do things wrong, I did them. And had a good time.

Then I started selling stories and wrangled myself onto the staff and ever since it’s been 50 new motorcycles to ride every year, each gleaming example perfectly suited to doing whatever it is we’re doing, and this excellence has been subtly working its magic . . . until this morning, when I was again out and about on a buzzing Single doing something it wasn’t supposed to be good at so we could go do something else it wasn’t supposed to be good at.

And I was enjoying it. What a super machine, I thought to myself, how good it is to hear the engine, feel the footpegs, slot comfortably onto and behind and atop the seat and bars and pegs which, after several years worth of Saturdays, now fit me perfectly.

What I will do in return, I promised the machine, is pay some well-deserved tribute to the dual-purpose motorcycle.

This goes against the trend, no doubt about that. Back when I was a lad, when Harleys ran enduros and Husqvarna build road-going Vee Twins—you could look it up—all motorcycles did whatever they were asked to do. Then road bikes got longer and lower and heavier and more liable to getting their corners knocked off. Dirt bikes got higher and lighter and less legal and despite excellent and plucky motorcycles like the Yamaha DT-1 and Honda XL250, the appeal of using one bike for everything declined, as did annual sales.

I have been waiting for this tide to turn. Had I held my breath during this vigil, I would by now be bright blue. The original gas crisis didn’t do it, nor have land closures, the price of trucks and vans and superbikes, the second gas crisis or the incredible leap in gas prices.

What we are dealing with here is philosophy and personal preference. I am in favor of superbikes and touring bikes and enduro and motocross bikes, just as I am in favor of all technical improvements, and the freedom of everybody to buy what they can pay for.

Nor can I argue on the basis of strict merit. The modern dual-purpose motorcycle is a good machine in its own right. The 1980 Yamaha DT is a better dirt bike than the works motocrossers of the past. A Honda XL500 is smoother, quicker on the drag strip and will carry as many people as the Honda CB450 that started the trend of big bikes from the Orient.

But. One can just barely mention the CB450 and the CBX in the same sentence. If Bob Hannah rode a DT against the latest YZ, he wouldn’t just lose. Even you and I could beat him.

No. What the dual-purpose motorcycle does, is everything. Being competent at all things, is, to me, as worthy of respect as being able to a few things very well. For reasons I don’t propose to explore here, the man who rides a motocross model in the woods or a megacylinder model on the highway thinks he’s doing better than the man who rides his dual-purpose bike on the highway to the woods. By me, he’s just going faster.

Which is why I was out and about on the ol’ 250 that morning. I was on my way to proving a point or—as the staff will tell me instantly they read this—I was out to make a gesture.

Joe Parkhurst, CWs own godfather, every year puts on a thing called the Laugh-In Trials.

The trials portion is always designed by world-class trials riders. Their idea of what a bunch of retreads and desk jockeys will be able to withstand has been, well, half the field usually retires after the first loop.

I have ragged Joe about this and for this year, he promised a class for non-trials bikes and non-AA riders. In exchange, although I didn’t tell him what I was up to, I figured I’d ride my 250, from home to track, in the competition, and home again, just as it used to be done when the lightweight scramblers were Triumph 500s.

After a lovely ride, I rolled up to the clubhouse and threaded my way through the parked trucks and vans. I was the only entrant who arrived on a motorcycle and the comments were that I was acting like myself, that is, rowing without both oars in the water.

Off we all went. I soldiered around the loop, dabbing here, getting stuck there. I cleaned one section and set low score of the day at another, the crawl dow n a creek bed. What I like best about riding an 8-in.wide motorcycle down a 6-in.-wide stream is, it’s so easy not to fall over.

Meanwhile, the ex-trials guys had done it to us again. Those riding trials bikes had a fun time. Those with open class motocrossers and full race desert weapons and leftovers borrowed from the back of the store did not. As usual, half the field decided an early lunch was better than making the second loop. I went ’round again, not improving much, and got back to the clubhouse for a late lunch.

And the awards ceremonies. The winners were two young racers on souped-up XR75s. Clever chaps. One seldom has to take the five-point penalty for stopping if one can pick up the motorcycle and run up hill with it.

There were other prizes. One came from Debbie Wilkins, a lady from Rider magazine. She rode a Penton. and rode it well, but because her magazine is for road motorcycles only, she donated an award for the best score on a street-legal bike.

Me. There were three license plates on the crowd. One was on a big desert cannon whose owner didn't like riding his 100mph machine at 2.25 mph. The other was ridden by a man who'd never been off road before. (His prize was for Most Crashes On the Day. And he only went around once.)

Victory was mine, fair and square.

The other prize, I didn’t deserve. But Henry N. Manney 111 was an observer on one of the uphill sections. 1 managed to stall atop a rock. My version is that 1 pulled the bike loose and slid gracefully backwards down the hill. But Henry is a wonderful storyteller and by the time the judges heard his version. 1 was the bashful w inner of the class known as Most Spectacular Crash.

When the cheering died down, everybody else got into their trucks, having gone riding for an hour or two. 1 started my engine on the second kick and rode home, having been a rider all day.

Best of all, I discovered something my bike and I can’t do. We finally needed a truck.

We had won more prizes than we could carry home.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue