One Year With A 1978 Maico 450 Magnum

The Big Maico Motocrosser is an Excellent Desert Bike

Ron Griewe

Early in 1978 we tested a new 450 Maico Magnum motocrosser. All the test riders were highly impressed with the Magnum's cornering and good handling. The big 450 engine had so much torque it seemed only right to try the machine in the desert, and to no one's surprise it worked as well in the desert as it did on a motocross course. Nothing broke during the test, not even a spoke, and the bike was ridden hard by motocross pros and desert experts.

and desert experts.

It seemed Maico had cured many of their past reliability problems. Our Western Advertising Manager, Jim Hansen, is a large person and fell in love with the 450 s pulling power. He bought the test machine

for a desert play bike. I had been looking for a long range test bike for Baja and desert and also decided to try a 450 Magnum. Maico West agreed to the proposal and supplied a new 450 in the shipping crate.

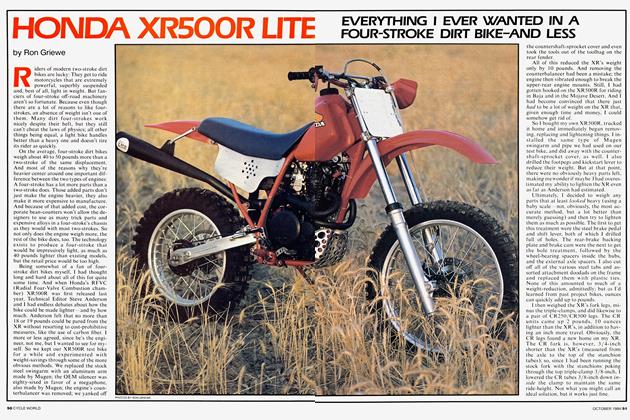

It’s always exciting uncrating and setting up a new motorcycle. After changing the front tire to a 3.25 Metzeler, the front w heel was bolted on. I removed the beautiful aluminum MX tank and installed a 4gal. Vesco. The Vesco fit like a glove—the front mounting bolt slid through the existing hole at the front of the frame and a rubber 0-ring held the back.

Fork oil was drained and 300cc of BelRay 5-weight mixed with 80cc of 10-weight

put back in. Maico West has recommended the mixture and it works great. Mixing weights of fork oil is something I have done for several years. Some of my friends are sure it is a waste of time. I don’t think it is. If a rider is sensitive to suspension compliance, the difference can be felt. Sometimes lOw is too harsh, 5w too soft, a mixture may be perfect. Several air pressures were tried and 12 psi proved about right for my use.

A Preston Petty front fender was installed. not because the stocker was bad. I just like the Petty's looks. Spokes were tightened but left stock. Many people change to a larger size but they looked large enough to me. Anyway, we hadn’t > broken any during our earlier testing. The stock 56-tooth rear sprocket was removed and a 49 took its place. The 13-tooth front sprocket was also replaced with a 14-tooth. The combination is good for 95 mph + . just right for the fast Mexican terrain. For engine protection I used a molded plastic skid plate called a Rad No Bolt that just snapped into place. It is nicely molded to the engine contours and doesn’t protrude or snag. I was highly skeptical about it staying on the bike without being bolted but after a year of being smashed into rocks and logs, it is still in place.

The stock Corte and Cosso shocks were replaced by Works Performance Supercrossers. The Supercrossers have a reservoir connected to their main body, have double springs and are rebuildable. And best of all. they are custom built for the bike, rider classification and terrain the machine is going to be used in; that is, desert, MX, play riding, etc. A K&N air filter took the place of the stock foam cleaner and K&N HA14 bars were installed. The front number plate was discarded and one with cable guards was installed. Control cables were replaced with nylon lined ones from International Motor Sports and two Yamaha cable guides were bolted to the number plate to guide the front brake cable. The slippery stock footpegs were replaced with sawtooth-topped ones from International Motor Sports. I made a non-slip rear brake pedal by cutting a piece off a length of square tubing, filing notches in it and then brazing the piece onto the top of the pedal. A large hole was then drilled through the pedal so mud, etc. would have a place to g°-

An off-road bike without a kick stand is truly a pain so I bought a stock kick stand for a late model Husqvarna and had Profab weld a pivot on the swing arm.

A small tool kit is always nice when riding in the wilds of Baja but the '78 Magnums didn’t have a rear fender loop, thus the tool bag had to be mounted on the handlebars. Several firms make nice large tool bags that strap to the bars. Most of them are too large and add a lot of weight to the front of a bike when full. Most also hit the tank when a combination of a big tank and rear-set bars are used. Finally I found a small leather one made for a chopper and modified it. It fit between the cross bar and bar mounts and cleared the tank with the steering at full lock.

The Maico intake hose between the Bing

and the cylinder is notorious for cracking and causing air leaks. I shopped around and found radiator hose that had the same inside diameter, cut it to length and threw the stock one in the trash—problem solved. Maico recommended installing springs between the carburetor and the cylinder to help support the carburetor, so I also did that. Next, small washers were welded to the screw heads on the carburetor top so removal in the field could be accomplished without tools. Maicos are imported with two different seats; one normal thickness, the other a thick GP design. But there is no way of knowing which a bike will have until the bike is removed from the crate. I

lucked out and got a thick one. perfect for off-road use.

Finally it was time to try the big 450. After a 150-mile loop through the Mojave Desert I was sure the Magnum was almost perfect for cross country use. Jetting wasn’t quite right for the 3000-4000 ft. elevation of the Mojave so next time out I took the time to rejet. Final jetting ended up a 75 pilot, 326 needle jet, stock needle, and 175 main.

The Magnum tracks as straight as a Husqvarna through desert terrain and slides firebreak roads like a good TT bike. Gearing and power band are good and the brakes stop well from 95 + . The only nega> tive part of riding a 450 Magnum off-road is fuel consumption. Mileage is poor, equaled only by a Yamaha 400YZ. The 4gal. tank will only go 50-60 miles with a fast rider aboard.

With about 1200 miles on the bike, 1 decided to race the Baja 500. Disaster struck during the prerun though. While in a 70 mph wheelie on pavement, the primary chain broke, locking the rear w heel and resulting in a long black S on the pavement from the rear tire. The bike was loaded on a truck and taken home for a ■complete tear down and inspection. The race was only one week away; no time to have the transmission parts magnafluxed for cracks. A visual inspection would have to do. The cases went back together and my race partner crossed his fingers. I tried to calm him by telling him how good all of the parts looked—great engineering, excellent metal, etc.

A new piston and fresh bore made the big M race*ready. Best put a hundred or so miles on it to make sure before the race. Race day was only three days away by this time. Fifteen miles were on the new engine when the rear hub broke; the sprocket bolts had been cracked when the chain locked on the pavement. We laced up a new rear hub, using larger sprocket bolts as a precaution. No time to break in the engine properly now. It was time to go to Mexico for the race. My partner was really nervous by now. 1 have a nasty habit of breaking our race bikes before he gets to ride, so his nervousness was justified.

1 started and had the class lead 20 miles into the course. The bike was running great, then a short paved section of the course (5 mi.) caused the engine to seize three times. 1 stopped and put a main jet three sizes larger in the Bing carburetor.

Then I started trying to repass the horde of people that had come by during the few minutes the jetting change had taken. Sixty-five miles into the race and only one racer in class left to pass, a transmission shaft broke. End of race. The shaft was probably cracked when the engine w'as apart, another byproduct of the primary chain breakage. Maico recommends draining the trans oil and checking the magnet on the drain plug after every ride, something I hadn’t been doing. When the big Maicos are ridden hard, primary chains are very short lived and should be changed often. Lack of proper maintenance had cost me another Baja finish.

Maico West tore the engine down and went through it. They put in a completely new transmission, (I am hard on transmissions so they willingly replaced all of the parts to satisfy my request.) They rebored the cylinder and installed a new piston, replaced the primary chain, and closely inspected the remaining parts. When finished, 1 took it and a spare primary chain home.

After riding bikes with gear primary drives for many years (most of which needed little or no maintenance), I found it difficult trying to keep track of guesstamated mileage and the every-ride chore of draining the trans oil and inspecting the magnetic plug for metal particles. The least mileage I got from a primary chain was about 400 mi., the most 700 mi. Jim Hansen consistently went 1500 mi. between primary chain changes, so rider style and classification play a large part in the maintenance schedule.

The Magnum went along on most testing sessions and soon became the standard by which other motocrossers and off-road bikes were compared. Handling, steering precision, cornering and suspension are almost perfect and the frame, flex free.

A few problems with soft metal were encountered during the test period: the forks tubes started to bend out like a chopper and the front and rear axles seemed to bend every ride and needed constant straightening. The fork tube problem w'as fixed by changing the tubes to American made chrome-moly steel parts, the axle problem was cured by using replacements from Works Performance. Both axles and fork tubes have been changed to chrome-moly steel on the ’79 Magnums, so the factory has cured any further problem.

Estimated mileage was kept throughout the extended test, the breakdown follows; Mojave Desert, 1300 mi.; mountains. 250 mi.: Baja playing. 1400 mi.; racing. 165 mi. total, over 3100 mi.

In addition to the transmission I munched, the following parts were used during the year-long test: two sets of fork seals, eight rear tires, three front tires, one rear fender, one set of brakes, five primary drive chains, three rear chains, three rear sprockets, two front sprockets, eight pairs of grips, three sets of clutch springs, one set of clutch plates, one kick starter lever, one carburetor slide and needle, one jet/needle, and two sets of control cables.

The stock rims and spokes went the entire distance, none of the engine bolts broke, the pipe didn’t have to be welded, no frame breakage, and nothing fell off.

The Works Shocks also proved an excellent choice. They w’ent the entire year with zero maintenance.

Sounds like a mountain of parts but things like tires, final drive chains, sprockets, brakes, and carburetor parts are normal maintenance pieces and reflect the hard use the bike w'as subjected to. I have a reputation for being able to break parts that most people never break. I even seize four-stroke Singles! The transmission problem was the result of lack of maintenance—not changing the primary chain at frequent intervals. The primary chain and clutch springs need to be changed often if the machine is ridden hard. If used moderately. they will last six months to a year. If raced by a pro or an expert, plan on changing the primary chain every four or five motocrosses. and every 400-600 mi. when raced off-road. Replace the clutch springs at the first sign of slippage. Don’t w'ait until the discs are ruined.

What does an owner of a 450 Magnum get in return for the extra maintenance required on the primary drive and clutch? Brute power, fine suspension, unbreakable frame and impeccable handling.

Would I buy a 450 Maico Magnum? You bet. I bought the test bike and converted it back to a motocrosser for my oldest son to compete on. @