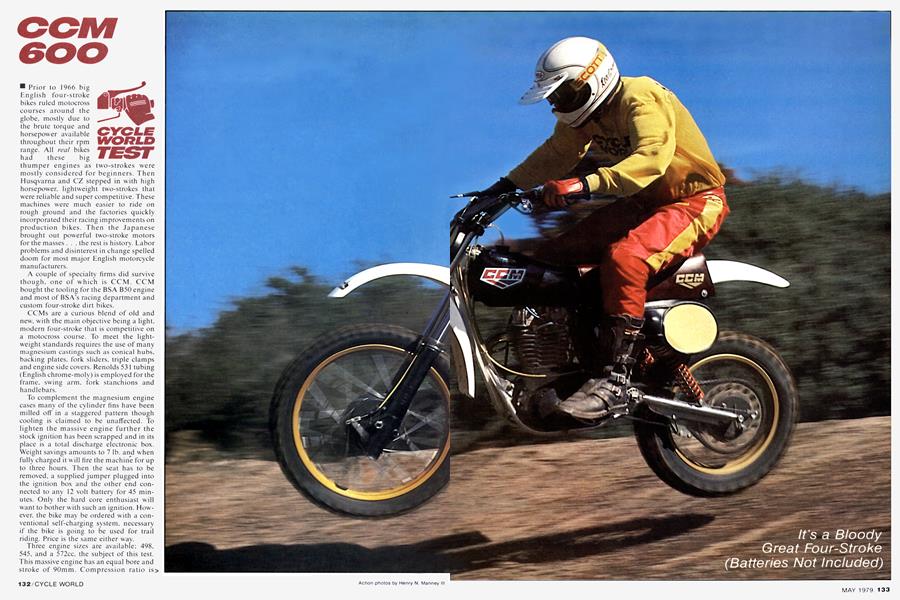

CCM 600

CYCLE WORLD TEST

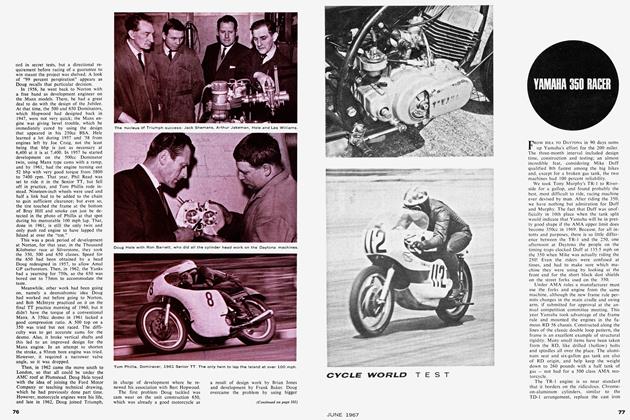

Prior to 1966 big English four-stroke bikes ruled motocross courses around the globe, mostly due to the brute torque and horsepower available throughout their rpm range. All real bikes had these big thumper engines as two-strokes were mostly considered for beginners. Then Husqvarna and CZ stepped in with high horsepower, lightweight two-strokes that were reliable and super competitive. These machines were much easier to ride on rough ground and the factories quickly incorporated their racing improvements on production bikes. Then the Japanese brought out powerful two-stroke motors for the masses . . . the rest is history. Labor problems and disinterest in change spelled doom for most major English motorcycle manufacturers.

A couple of specialty firms did survive though, one of which is CCM. CCM bought the tooling for the BSA B50 engine and most of BSA’s racing department and custom four-stroke dirt bikes.

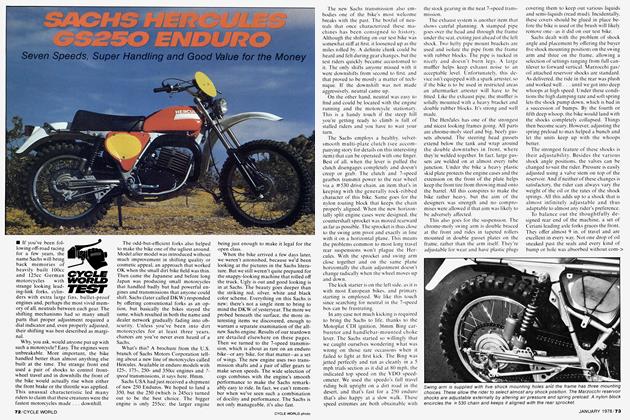

CCMs are a curious blend of old and new, with the main objective being a light, modern four-stroke that is competitive on a motocross course. To meet the lightweight standards requires the use of many magnesium castings such as conical hubs, backing plates, fork sliders, triple clamps and engine side covers. Renolds 53 1 tubing (English chrome-moly) is employed for the frame, swing arm, fork stanchions and handlebars.

To complement the magnesium engine cases many of the cylinder fins have been milled off in a staggered pattern though cooling is claimed to be unaffected. To lighten the massive engine further the stock ignition has been scrapped and in its place is a total discharge electronic box. Weight savings amounts to 7 lb. and when fully charged it will fire the machine for up to three hours. Then the seat has to be removed, a supplied jumper plugged into the ignition box and the other end connected to any 12 volt battery for 45 minutes. Only the hard core enthusiast will want to bother with such an ignition. However. the bike may be ordered with a conventional self-charging system, necessary if the bike is going to be used for trail riding. Price is the same either way.

Three engine sizes are available; 498, 545, and a 572cc, the subject of this test. This massive engine has an equal bore and stroke of 90mm. Compression ratio is> 10.0:1 and all sizes are available with either a three or four-speed transmission. Many internal parts have been scrapped in favor of stronger ones: the crank and rod are custom made, same with pistons, valves and some transmission gears. A twovalve head is employed but a four-valve Weslake head will be available in the near future. Primary drive is by a small double row chain and the clutch is a stock fiveplate BSA part. In true British form, the shift lever is on the right side, the proper place for it. the English tell us. For the home market CCMs come with a traditional up for low shift pattern, but ours had been converted to a down-for-iow pattern to reduce confusion. The kick starter mechanism is another BSA holdover. It was a poor design when BSA used it and is even more outdated today. If the kick lever happens to bounce back or get pushed rearward while the motor is running. disaster will strike in the form of a blown transmission and possibly the center cases. To help protect against this, the CCM was delivered with two rubber bands holding the lever forward. One band hooks around the engine clutch lever and connects to the end of the kick lever. The other rubber band (cut from an innertube) hooks under the footpeg and stretches to the pedal’s end. A poor fix for bad engineering.

Good sawtooth footpegs are supplied and mounted to plates that bolt to the engine’s side cases.

The CCM frame is a work of pipebender’s art. A large diameter front downtube splits into two smaller tubes that circle under the engine cases and then turn upward, terminating behind the tank at the large backbone that is tied into the downtube by another substantially curved tube and sizable gusset plates. Smaller tubes under the seat form a triangle and provide a place to mount the laid down gas Girling shocks. The main frame tubing also serves double duty as an oil reservoir.

A straight-tube swing arm with the shock mounts at mid-arm and full length gusseting on the lower edge is used. It differs from the normal; chain adjustment is made at the pivot, utilizing a cam system. This in theory is a stronger way to do it. The axle can be tightened without interference from adjusters. And because the cams have holes through them for the position screws, alignment is always perfect.

The hand-made aluminum fuel tank holds only 1.5 gal. of premium. Getting into the small filler isn't much fun. the cap required more than three full turns to remove and it's hard to tell when the tank is full until it sloshes over. We couldn’t figure out the reasoning for such a fine thread on the filler neck until we realized the cap was actually an Amal carburetor top! Maybe CCM got a buy on a truck load of them, who knows. After spending the time required to build an aluminum tank it would seem logical to apply a quality paint job but the opposite is true as the black paint looks like the shop apprentice dabbed it on with a rag. The painter didn't bother covering the filler hole before starting either; paint is inside and will surely end up in the carb if a fuel filter isn't installed. The tank finish seems in conflict with the beautifully finished frame and swing arm.

The seat is another strangely finished item. Its shape and foam firmness can't be faulted, nor the quality of the cover, but the color—a blending swirl of maroon and black—looks like it came from a bus depot greasy spoon. It bolts to the beautiful frame in a non-professional manner, too. The factory didn't use flat brackets or a

cross-tube for the attaching bolts, instead a ragged hole has been hand drilled through each frame rail and a full-thread machine screw and self-locking nut hold it on. At best it's a poor set-up.

The rear fender is one of the few nonBritish parts on the bike, made by Falk in Germany, the people who make the plastic parts for Maico. The front is by Stadium, an English firm that supplies fenders for Husqvarna. Molded front and side number plates are also Stadium built. Strangely. these molded side plates are attached to the frame by common sheet metal screws.

The big thumper starts easily if the correct procedure is followed. The drill differs from normal beginning with the ignition switch; it is a knurled knob

reached through a hole in the right side number plate. The hole is only large enough for one finger but with practice one finger can turn the knob clockwise far enough, then a small red light signals that the electronic box is on. We found it was easier to turn on before mounting the machine. Next, the two rubber bands are unhooked, the lever folded out and pumped until a compression stroke is felt. Then bump the lever past the compression stroke and slowly push the lever to its lowest point, let the lever return to the top position and jump on it pretending you're mad. Don't worry about it backfiring and launching you over the bars like the older British Singles were fond of doing. The electronic ignition has 35°of advance/re-> tard designed into it and eliminates such bad manners. When warm, one kick will fire the bike right up. when cold it usually takes two. Blip the throttle and let the engine warm up. When warm, place your left hand on the throttle, twist around and hook the bands around the kick lever, w'hoo . . . Pull the clutch in. place the righthand shift lever in low', release the clutch lever and kill the engine. Unhook the damn rubberbands and start the procedure all over, being extra careful to prevent another stall.

A couple quick laps around Saddleback Park’s practice MX course proves about as much fun as wrestling a gorilla. The importer warned us about the high friction fork scrapers: “Pump oil around them to reduce the friction and stickiness.” he said. We did as we were advised but the forks still showed minimal travel and made riding on rough ground impossible. We removed them with a pocket knife and tried it again. Much better. Now they w'ere complying with the irregularities. Both ends are set up rather stift’, but this is an all out MX racer and is suspended accordingly. It’s a lot more fun to ride with the forks working but three more laps and our arms were wasted. We loosened the beautiful chrome-moly bars and pushed the ends way down, trying to compensate for their height. They are shaped right but way too high for anyone less than six-foot-six. Rotated down, the seat/peg/bar relationship is about right and our arms quit seizing up.

The three-speed transmission shifts smoothly but we have to continually remind ourselves it is on the right. On fast courses shifting won’t be required much anyway, as two gears are all that are needed; second and third, and seldom second. Torque is comparable to a tractor and abundant power is every place in the rpm range.

Both brakes on the CCM are the same size. The front works perfectly, the rear is almost unusable. The problem is a brake pedal that furnishes too much leverage for the generous brake size. We soon learned to ignore it and use the front brake and engine braking to control the rear. Most first time four-stroke riders will think they are going to be thrown over the bars w hen they chop the throttle on the 600 for a turn. It feels like an anchor has been dropped any time the throttle is turned completely off. This engine braking instills great confidence in downhill situations and uphills are treated as level ground. We couldn't find an uphill at Saddleback that the CCM couldn't conquer, most of them in second gear.

Once the suspension loosens up and the rider adapts to the bike it will circle most motocross tracks as fast as a good twostroke. It is a neutral handler; track through a corner or slide it, the rider makes the choice. Steering is precise and accurate without being overly quick. Balance is excellent and flex nonexistent. Good hantiling chassis don't just happen, they are the result of years of racing development. CCM competed in world motocross for several years; running their supposedly antique four-strokes against works twostroke racers from Japan, Sweden and other parts of Europe. They raised quite a few eyebrows by finishing in the top 10 year-end standings a couple of times. More recently Goat Breker won the 1978 four-stroke Nationals at Carlsbad. California on one. It was like our test machine with the exception being a shock change to Ohlins. An even more impressive win when we were told he had practiced only two hours on it prior to the race.

continued on page 171

CCM 600

SPECIFICATIONS

$3500

DIMENSIONS

FEATURES

continued from page 141

The CCM is a fun bike to trail ride on. It draws an instant crowd and trying to find a hill it won’t climb becomes a challenge. It is also a competitive motocrosser, but we doubt many will be used for MX on a regular basis. The bike is a hand-made novelty that combines beautiful workmanship on the frame, inexcusably sloppy paint on and in the tank, an antique engine with some updating, many light magnesium parts and the best handling of any slock four-stroke today.