CAGIVA/DUCATI PASO

CYCLE WORLD TEST

WHEN MORE THAN A YEAR PASSES BETWEEN THE APpetizer and the main course, you can build up a powerful appetite. And when the appetizer is a motorcycle as promising and as tantalizing

as the pre-production Ducati Paso we rode for our September, 1986 issue, the production-bike main course had better be damned good.

After all, the translation from prototype hopeful to production-line reality has been known to cook the flavor out of many a fine motorcycle design. So, that hand-built Paso we rode in Italy last year could have been misleading; it could have been faster, lighter and better-handling than anything the company was able to sell on a mass-produced basis. On the other hand, a year is plenty of time to pick the bugs out of the stew, to fix the few complaints we had about what was otherwise an impressive, captivating package.

For those of you who missed the opening act, the 750 Paso is Cagiva’s top-of-the-line sportbike, a street-legal adventure in styling and performance. It’s also a bike that Cagiva, the new owner of the Ducati name, hopes will

nullify any doubts that hardcore Duck fans have about the company’s ability to carry on the best Ducati sporting tradition. Since Cagiva’s acquisition of Ducati in 1984, the only streetbike offered to an anxious American riding public has been the Alazzurra 650—a fine machine but hardly a firestarter of a sportbike worthy of the Ducati legacy.

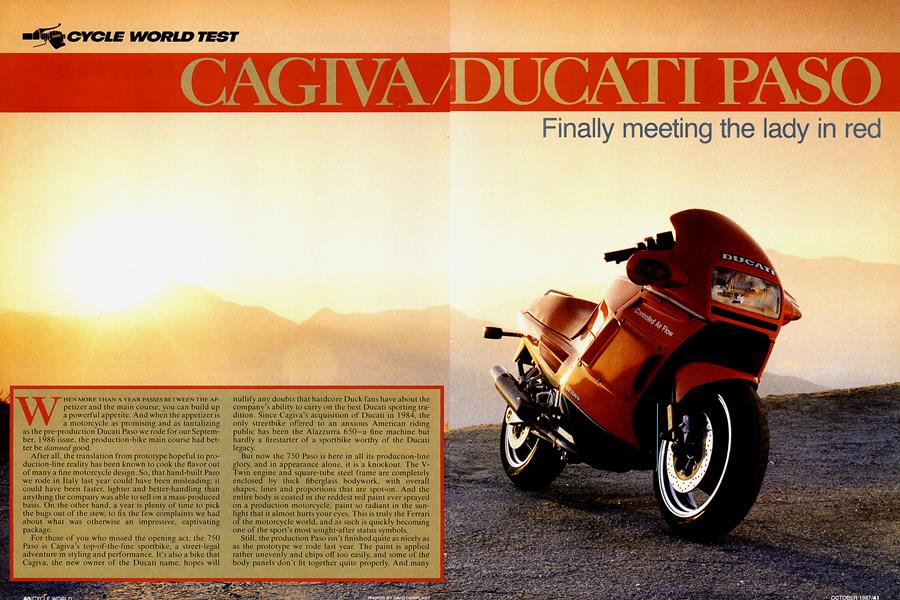

But now the 750 Paso is here in all its production-line glory, and in appearance alone, it is a knockout. The VTwin engine and square-tube steel frame are completely enclosed by thick fiberglass bodywork, with overall shapes, lines and proportions that are spot-on. And the entire body is coated in the reddest red paint ever sprayed on a production motorcycle, paint so radiant in the sunlight that it almost hurts your eyes. This is truly the Ferrari of the motorcycle world, and as such is quickly becoming one of the sport’s most sought-after status symbols.

Still, the production Paso isn’t finished quite as nicely as as the prototype we rode last year. The paint is applied rather unevenly and chips off too easily, and some of the body panels don’t fit together quite properly. And many of the production bike’s numerous aluminum forgings don’t have the smooth, polished look of the prototype’s. But remember that the hand-built bike we rode at the factory was . . . well, perfect. And even if this Paso isn’t flawless, it still is just about the most visually striking motorcycle made, a bike guaranteed to elicit more comments per mile than anything else you’ve ever ridden on—or in.

Finally meeting the lady in red

It’s also guaranteed to result in at least one encounter with the law on every ride of any length—as evidenced by the highway patrolman who stopped one of our riders for doing 100 mph on ruler-straight Interstate 5. The officer hadn’t clocked him doing 100, hadn't even seen him doing 100—and, in fact, the rider had not been exceeding the 65mph limit. But after one look at the Paso, the cop just knew the rider had been doing something highly illegal, so he did his duty and issued a stern warning.

Not that the Paso isn’t capable of earning a legitimate speeding ticket. It certainly is an able performer, for its 90degree V-Twin engine is at least as powerful as any twincylinder streetbike motor available in the U.S.—including some that have nearly twice the displacement.

Obviously, the Paso can’t even hope to compete with today’s multi-cylinder sport-racer motors in terms of pure speed and acceleration; but ridden at a pace more suitable for sport-touring than backroad berserking, the Paso is surprisingly fast—and a sheer delight to hear and feel. The throaty rumble of the V-Twin entertains the ears; and although the 90-degree V-spread makes for almost vibration-free running, the gentle throb of the staggered power pulsations has an almost soothing effect on the areas of the body that come in contact with the machine. And because the torque output seems almost not to vary from just above idle to just below redline, the Paso requires very little gearshifting to be ridden at a rapid pace on a curvy road.

The 748cc, sohc motor, which still features the industry’s only desmodromic valve actuation, is essentially the same powerplant that began life in the 1979 Ducati 500cc Pantah. It has gone through several stages of evolution since then, first becoming a 600. then a 650. and most

recently seeing service in the 750cc Ducati FI racebike. The Paso uses the same large valve sizes as the FI, but is detuned through more-restrictive intake and exhaust systems.

Carburetion also is different from the FI’s. Instead of using twin Dell’Ortos, the Paso employs an automotivestyle, dual-throat Weber. Cagiva chose this carb to help in meeting America’s tough emissions requirements; and, unfortunately, this is one area where the production machine is largely unchanged from the prototype, for the carburetion is erratic, just as it was on the bike we rode last year. The mixture seems so weak at or just above idle that the engine sometimes dies at stoplights, and the bike often requires excessive revving and clutch-slipping to pull away from a dead stop.

Even out on the highway, well away from traffic lights, the carburetion causes problems. When the throttle is held at a steady opening during open-road, legal-speed cruising, the leanness gradually causes the bike to slow down. Dialing the throttle open wakes the motor up again, but this trait is quite annoying and makes it almost impossible to hold a steady speed.

Another pre-production glitch that never got ironed out concerns the dry clutch. Last year, we reported that the prototype’s clutch felt worn-out and abused, but the clutch on our brand-new production Paso feels much the same. The all-metal clutch tends to engage rather roughly anyway; but when it is subjected to even a little extra slippage when starting off—a tactic often made necessary by the lean carburetion—it squawks and chatters.so loudly that it sounds like you’re grinding up tomcats in the gearbox. Not the sort of behavior one expects from a highperformance status symbol.

Many of the good points we raved about, though, also survived the transition from pre-production to production. One big area is handling, where the assembly-line Paso is everything we expected it to be. The bike did gain a little weight, partly because the prototype fuel tank was fiberglass and the production tank is steel, and partly because the bike we rode last year didn't have turnsignals and mirrors.

But even though the Paso is a tad heavy for a sporty Twin, it still sticks to its line through corners as though it were on rails. When you ride this bike, you're the one in charge; you pick the line you want, lean as far as you want and go as fast as you want. The bike simply does as it’s told.

Credit much of this competence to the Pirelli MP7S radial tires, which stick to the road more tenaciously than chewing gum sticks to your shoes. And Paso riders will quickly come to love the front brake, which is extremely powerful yet very predictable. Conversely, the rear brake is high in effort and low in feedback, but with such a wonderful front brake on the job, we almost didn’t care.

If you have any notion of showing up at the local roadraces, though, take our advice: Don't. Cagiva clearly designed the Paso for road riding, not track racing. Aside from the engine’s lack of competitive horsepower, the steering isn't quick enough and the riding position isn’t aggressive enough for all-out roadracing.

On the bright side, however, the Paso is much more comfortable than most of the new-generation street-racers from Japan—or for that matter, the hardcore sportbikes that traditionally have come from Ducati. Cagiva compromised in all the right areas to come up with a streetable flashbike. one that is more accurately matched up with the big sport-tourers such as Honda’s Hurricane 1000 and Yamaha's FJ 1200.

In that light, the Paso compares quite favorably, doing everything in its power to pamper its rider on long rides. The suspension-usually a sore spot on Italian bikes—is excellent. The Marzocchi fork has externally adjustable rebound damping and a ride that strikes an admirable compromise between corner-carving and all-around road riding. To our surprise, our test Paso came equipped with a Marzocchi rear shock instead of the Ohlins that was on the pre-production bike, but we have no complaints about its behavior.

We also are unable to fault the Paso’s ergonomics, for it seems to fit just about everyone. The bike is scaled for

larger riders, which is quite different from what we find with most Japanese sportbikes. Footpeg location is just about right for riders with long legs; and because the bodywork is all-enclosing, there are no sharp fairing edges for that long-legged rider’s knees to bang into. And it’s hard to imagine a posterior that wouldn’t fit the well-shaped seat. So despite the Paso’s appearance of being a living-room showpiece, it is, as we said, a bike made for riding.

Nonetheless, it’s hard to escape the feeling that the Paso was rushed onto the market before it was completely finished, for there are numerous annoyances that should have been dealt with before the assembly line was fired up. Getting the bike on its centerstand, for example, is a strength test many riders are going to fail. And not only do the round mirrors glued onto the triangular backsides of the turnsignals look like a cheap afterthought, their lowlevel location (in line with the rider’s hips) allows only a narrow, partially obstructed view of the road behind—and virtually no view at all when the Paso is fitted with soft saddlebags for a sport-touring trip. There’s also a tripmeter that can’t be seen in the dark, a neutral light that can’t be seen in the sun, an absence of places on which to hook bungie cords, and the unsettling fact that the front wheel rams the lower edge of the fairing under hard braking.

We also were disappointed that Cagiva was unable to hit its original target price of $5800 for the Paso. But rather than being an oversight on the part of the company, the $6377 list price simply reflects the stability of the Italian lire relative to the ongoing devaluation of the dollar.

But despite our disappointment with the Paso’s price and some of its details, we can’t honestly say we’re disappointed in the bike as a whole. Glitches and all, this is a fun bike to ride—and to be seen riding. And that simply reinforces our feelings that the Paso has the potential to be Italy’s pride and joy, a red-white-and-green standout that can easily hold its own against the best the Japanese have to offer.

But it’s not there yet, not quite. Maybe another year of simmering is needed before this gourmet dish will be fully cooked. ga

CAGIVA,

DUCATI PASO

$6377

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialOh, Why, Tell Me Why

October 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeSherlock And the Golden Hour

October 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1987 -

Roundup

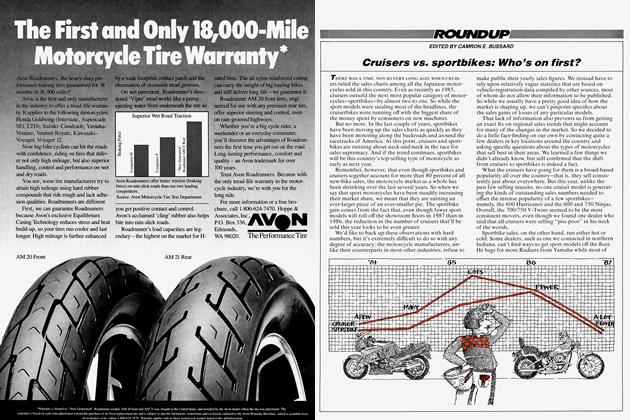

RoundupCruisers Vs. Sportbikes: Who's On First?

October 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Sdr Rocket

October 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia's Expansion Plans

October 1987 By Alan Cathcart