YAMAHA XS1100 SPECIAL

CYCLE WORLD TEST

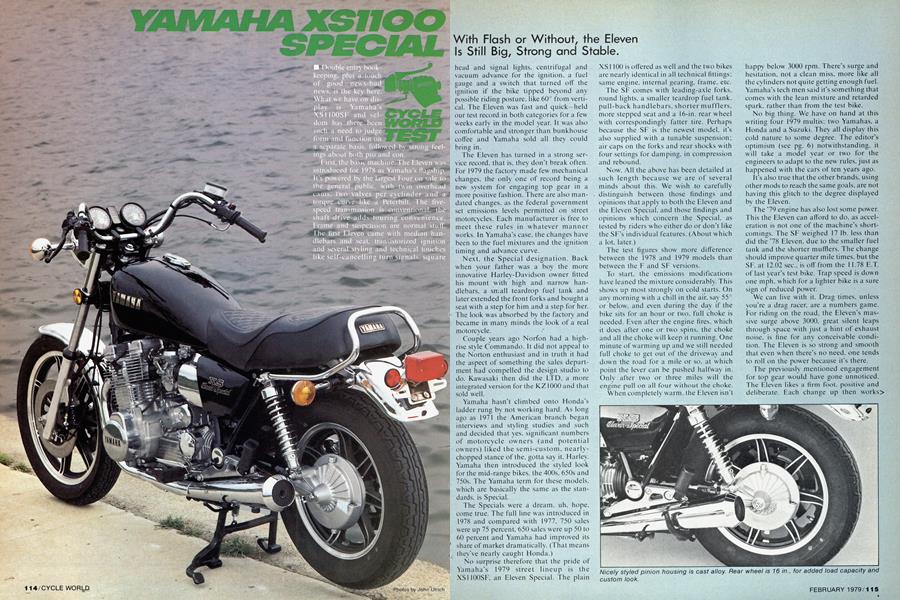

Double entry book-keeping, plus a touch if good news-bad news, is the key here. What we have on display is Yamaha's XS1100SF and seldom has there been such a need to judge form and function on a separate basis, followed by strong feelings about both pro and con.

First, the basic machine. The Eleven was introduced for 1978 as Yamaha's flagship. It's powered by the largest Four on sale to the general public, with twin overhead earns, two valves per evclinder and a torque curve like a Peterbilt. The fivespeed transmission is conventional, the shaft drive adds touring convenience. Frame and suspension are normal stuff. I he first Eleven came with median handlebars and scat, transistorized ignition and several styling and technical touches like self-cancelling turn signals, square head and signal lights, centrifugal and vacuum advance for the ignition, a fuel gauge and a switch that turned off the ignition if the bike tipped beyond any possible riding posture, like 60° from vertical. The Eleven was fast and quick—held our test record in both categories for a few weeks early in the model year. It was also comfortable and stronger than bunkhouse coffee and Yamaha sold all they could bring in.

With Flash or Without, the Eleven Is Still Big, Strong and Stable.

The Eleven has turned in a strong service record, that is, they don’t break often. For 1979 the factory made few mechanical changes, the only one of record being a new system for engaging top gear in a more positive fashion. There are also mandated changes, as the federal government set emissions levels permitted on street motorcycles. Each manufacturer is free to meet these rules in whatever manner works. In Yamaha’s case, the changes have been to the fuel mixtures and the ignition timing and advance curve.

Next, the Special designation. Back when your father was a boy the more innovative Elarley-Davidson owner fitted his mount with high and narrow handlebars, a small teardrop fuel tank and later extended the front forks and bought a seat with a step for him and a step for her. The look was absorbed by the factory and became in many minds the look of a real motorcycle.

Couple years ago Norton had a highrise style Commando. It did not appeal to the Norton enthusiast and in truth it had the aspect of something the sales department had compelled the design studio to do. Kawasaki then did the LTD, a more integrated version for the KZ 1000 and that sold well.

Yamaha hasn't climbed onto Honda’s ladder rung by not working hard. As long ago as 1971 the American branch began interviews and styling studies and such and decided that yes. significant numbers of motorcycle owners (and potential owners) liked the semi-custom, nearlychopped stance of the. gotta say it, Harley. Yamaha then introduced the styled look for the mid-range bikes, the 400s. 650s and 750s. The Yamaha term for these models, which are basically the same as the standards. is Special.

The Specials were a dream, uh. hope, come true. The full line was introduced in 1978 and compared with 1977, 750 sales were up 75 percent. 650 sales were up 50 to 60 percent and Yamaha had improved its share of market dramatically. (That means they've nearly caught Honda.)

No surprise therefore that the pride of Yamaha’s 1979 street lineup is the XS1100SF. an Eleven Special. The plain XS1100 is offered as well and the two bikes are nearly identical in all technical fittings; same engine, internal gearing, frame, etc.

The SF comes with leading-axle forks, round lights, a smaller teardrop fuel tank, pull-back handlebars, shorter mufflers, more stepped seat and a 16-in. rear wheel with correspondingly fatter tire. Perhaps because the SF is the newest model, it’s also supplied with a tunable suspension; air caps on the forks and rear shocks with four settings for damping, in compression and rebound.

Now. All the above has been detailed at such length because we are of several minds about this. We wish to carefully distinguish between those findings and opinions that apply to both the Eleven and the Eleven Special, and those findings and opinions which concern the Special, as tested by riders who either do or don’t like the SF’s individual features. (About which a lot. later.)

The test figures show more difference between the 1978 and 1979 models than between the F and SF versions.

To start, the emissions modifications have leaned the mixture considerably. This shows up most strongly on cold starts. On any morning with a chill in the air, say 55° or below, and even during the day if the bike sits for an hour or two. full choke is needed. Even after the engine fires, which it does after one or two spins, the choke and all the choke w ill keep it running. One minute of warming up and we still needed full choke to get out of the driveway and down the road for a mile or so. at which point the lever can be pushed halfway in. Only after two or three miles will the engine pull on all four w ithout the choke.

When completely warm, the Eleven isn't happy below 3000 rpm. There’s surge and hesitation, not a clean miss, more like all the cylinders not quite getting enough fuel. Yamaha’s tech men said it’s something that comes with the lean mixture and retarded spark, rather than from the test bike.

No big thing. We have on hand at this writing four 1979 multis; two Yamahas, a Honda and a Suzuki. They all display this cold nature to some degree. The editor’s optimism (see pg. 6) notwithstanding, it will take a model year or two for the engineers to adapt to the new rules, just as happened with the cars of ten years ago.

It's also true that the other brands, using other mods to reach the same goals, are not having this glitch to the degree displayed by the Eleven.

The ’79 engine has also lost some power. This the Eleven can afford to do. as acceleration is not one of the machine’s shortcomings. The SF weighed 17 lb. less than did the '78 Eleven, due to the smaller fuel tank and the shorter mufflers. The change should improve quarter mile times, but the SF. at 12.02 sec., is off from the 11.78 E.T. of last year’s test bike. Trap speed is down one mph. which for a lighter bike is a sure sign of reduced power.

We can live with it. Drag times, unless you’re a drag racer, are a numbers game. For riding on the road, the Eleven’s massive surge above 3000. great silent leaps through space with just a hint of exhaust noise, is fine for any conceivable condition. The Eleven is so strong and smooth that even when there’s no need, one tends to roll on the power because it's there.

The previously mentioned engagement for top gear would have gone unnoticed. The Eleven likes a firm foot, positive and deliberate. Each change up then works> well, a thunk from the box marking each shift. It's possible to find neutral involuntariis if one's yank up isn't firm enough. (By the same rule, finding neutral on purpose. on the way down, is easy.)

Clutch pull isn't noticeable. Nor is throttle resistance, perhaps because the Eleven is working so easily, w ith such small throttle openings at cruise, that the slides are barely cracked and the springs barely stretched.

The gadgets are welcome, sort of. Not in two years have we had occasion, knock wood, to test the tip-over shutoff switch, nor do we wish to. The fuel warning light comes on first under acceleration, then glows steadily for several miles before the tank must be switched to reserve. A reminder of a reminder, in a way. No harm, but no provable benefit, either.

The automatic cancel for the signals is clever. Works with a computer y'know. which counts up the time and distance traveled and then throws its own switch. There's a rider-controlled cancel as well.

One of our riders, though, noticed that sometimes he and the computer didn't agree as to how long the signal should be on. as in riding up to a stop sign with left turn planned. He found himself thumbing the button when he knew the system would accept his judgment, that is. he was workin" for the machine rather than the wav we like to think this stuff works. Does keep one from leaving the blinkers on. though, so it can't be all bad.

The Eleven SE suspension is something of a puzzle, not quite up to expectations.

The Eleven's basic geometry has been retained for the SF. This is no accident.

The XS750 Special has leading axle forks, di flerent steering head angle and different trail than does the XS750. For the F leven Special, though, the designers retained the standard Eleven's Fork angle and pulled the stanchion tubes closer to the steering head, keeping the front axle and steering head in their original relationship, which 'gives the same trail.

The extra here is the air forks and rear suspension damping feature. Again, this has been done \\ ith some care. The factory provides a section in the owner's manual, with a sliding scale: air pressure in psi. damping settings from 1 to 4. rear spring preload A through E. ( There are the normal five settings for the latter, but the engineers apparently didn't want to use two sets of numbers, ergo the letters.)

For solo soft, the factory recommends forks at 5.7 to 14 psi. springs anywhere between A and E. dampers on I. Same for solo firm or with passenger, except the damping goes to 2. Tor passenger and/or equipment, such as fairing, saddlebags, etc., the forks are pumped lo 14 to 2J psi. the dampers go onto 3 and the springs should be between C and E.

Maximum, which appears under the passenger and add-on heading, is 21 psi. E for the shocks and 4 for the dampers.

The damping variation is nicely done, w ith a thumb wheel at the top of the shock bodv The wheel controls the si/e of the opening which limits the flow of the shock fluidand thus damps the motion of the motorcycle on its springs. T he hole works on both compression and rebound and the adjustment is expressed in terms of percent: if 4 is considered maximum damping, 3 is 8b percent of 4 and 2 is 75 percent and so forth. (The same chart reverses the measurement. If 1 is 100 percent, then 2 is 113 percent, etc.)

The results are less than this controlled development would seem to justify f irst, the SF is firmly sprung on the softest ol ail settings. Perhaps emphasized by the upright riding position, or perhaps influenced by the large and heavy rear wheel and tire, the Eleven seems to react to ripples aftd holes more than, say, the Suzuki CJSFOW. The ride is choppier than we remember the ’78 Eleven being. This is on full soft. Even less than full soft, as we let all the air out of the forks to see if that helped. It didn't.

Firrtfing the suspension, in stages, solo, only made firm Stifter still. What this seems to mean is that the SF is expected to be sold and used for a touring bike, so it comes with suspension ready for extras, l ike à pick-up truck, the only way you can get the ride to smooth out is to load the thing to its capacite.

Whether the system justifies itself depends on usage. Because the suspension tuning works best as a compensator for load, and because the XSI1 in either form isn't a canyon racer, we believe the air caps and adjustable shocks would have been better as an option for the SI or the F than as standard equipment on the SF.

Handling isn't such a problem. First, the Eleven is a big bike. As we saw last year, when all the big Factories released their rockets at about the same time, the bigger the motor the heavier the machine. The Eleven is thus the biggest of the bunch. (Harleys excepted, although the 74 and 80 both outweigh the Eleven, so the rule remains unbroken.)

The Eleven is a good big bike. Around town the steering is heavy and the bike begins to turn in at slow speeds, when gravity pulls dow n harder than centrifugal force is pushing away. This goes away above 20 or 30 mph. In a straight line, at anv speed you care to name or we'd just as soon not print, the Eleven goes like an arrow. At normal cruising speeds or brisker, the stiff suspension helps in handling the reversed rise and fall of the rear suspension. Most of the time the rider only notices the rear of the bike lifting under power from a dead stop. The Eleven is firmer than. say. a BMW. while having less suspension travel and there’s no feeling of dive under braking or when the throttle is rolled shut.

Linder most conditions. The Eleven is heaw. The frame is stiff. So are the forks and the swing arm. especially with the generous size of the sw ing arm bearings and the arm itself There is no hinge in the middle. The Eleven will track around a bumpy sweeper, assuming a rate of travel in the sporting class but no faster, w ith no hunting of the bars or flex from below.

If the rider proceeds with smoothness. The Eleven does not like sudden inputs. None of this flick from side to side or wrench the bike upright stuff. Hard braking in a turn or sudden pow er before you're through the turn cun use up all the traction and then you're astride a clumsy beast indeed. At full cornering speed, quickly rolling off the power will sink the SF

toward the «round. The pegs will scrupe on> both sides and both stands will ground on the left. The Eleven is no RD400, which is why Yamaha offers lots of different models. Further, the SF didn’t strike sparks until we began experimenting, going as fast as the bike would go. The Eleven has plenty of ground clearance and grip for riding as the bike is supposed to be ridden.

Braking performance is down this year, a phrase used here because the SF has the same brakes—two front discs, one rear disc—as the plain Eleven had last year. The test bike wore Bridgestone Magnum Mopus tires, which did well in general in the front tire tests conduction in the January issue, but which didn’t stop as short as some other tires in the group. Our records from 1978 don’t show what tires the previous XS1100 had, sorry, but it wasn’t these because they weren’t on the market then.

The test riders also wonder if the pullback bars had an influence. The front brake lever isn’t in the usual place and it could be this hampered the riders in getting maximum braking and control.

So much for facts and figures. Now for the Special section.

As detailed, the SF comes with smaller tank, stepped seat, higher and narrower bars and a few other things. The above items are the major differences and the ones with emotional appeal, pro and con.

As art, the SF is an unquestioned success. Custom styling on little bikes looks foolish. On big bikes, not so, logical considering where the look came from.

Our test bike came in Black Gold, the other choice for this model being red. The paint is black with gold flecks and all hands agreed that the paint, the lack of stripes and decals and other disguises of the stylist’s trade, work. Black, chrome and aluminum. Enough to make any motorcycle enthusiast stop and admire.

What this treatment also does is alter the Eleven’s ergonomics, the relationships of controls, the posture the rider can or must assume.

The bars and seat prop the rider up. The laid-back stance isn’t wrong. There is a feeling of command, even, the attitude of the man at the helm, in control. The seat shape works if that’s where you want to sit.

Both are not far from standard touring and our resident tourist likes the SF a lot. Behind a windshield, he says, the upright rider is comfortable. If we’d try it with a fairing, we’d like it. And several of the staff would rather have their feet forward and butts planted squarely in the saddle.

The guys who ride for several hours at a time, on bare bikes rather than behind fairings, like the bars least. Even those who appreciate the style of the SF object to styling for its own sake. Handlebars and other controls are supposed to improve control and comfort, they say. Motorcycles are supposed to fit people, not bend the rider into a shape dictated by the whim of fashion. The sit-up-and-beg posture keeps you hanging on against the wind and it’s tiring.

Finally, there are those who plain object to anything except a Harley looking like a Harley; like Harleys or hate ’em, it’s possible to admire their distinction and complain when other brands infringe on the Harley image.

Serious stuff. The emotional content we'd best leave alone. Emotion is stronger than reason because you can’t argue with it.

Hence the double-entries and the multiple division.

Technically, the Yamaha XSl 100 in any form is a fine machine. Beefy, powerful, smooth and well put together. In F or SF versions, the Eleven delivers what it promises. In the case of the SF, how the buyer feels about the controls and positions will depend on the individual and can be decided by riding both and deciding from there. All we can report about comfort is, some of us were and some of us weren’t. Whether you’d rather have the bigger tank or the teardrop tank depends on usage, another personal equation.

For the rest, if you like Yamahas to look like the SF, you’ll like the SF. ES

YAMAHA XS1100 SPECIAL

$3699

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWhy the Future Isn't My Secret

February 1979 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1979 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound-Up

February 1979 -

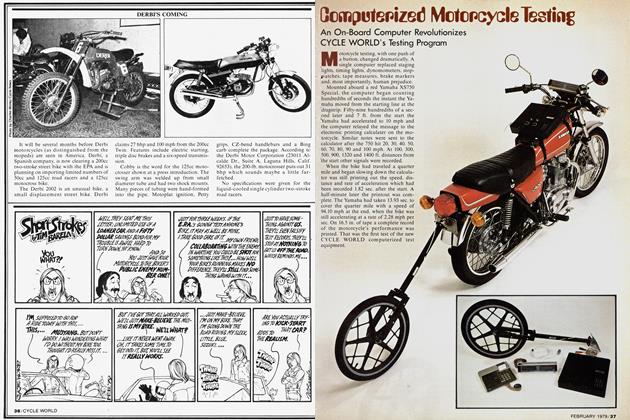

Short Strokes

February 1979 By Tim Barela -

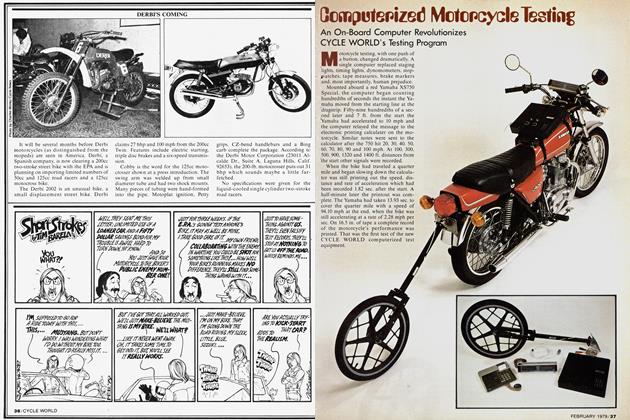

Technical

TechnicalComputerized Motorcycle Testing

February 1979 -

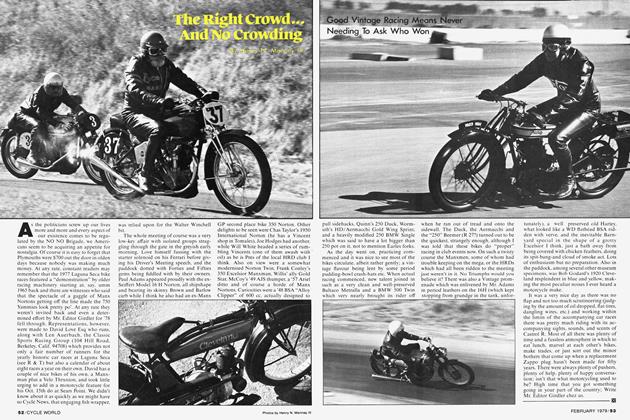

Features

FeaturesThe Right Crowd... And No Crowding

February 1979 By Henry N. Manney III