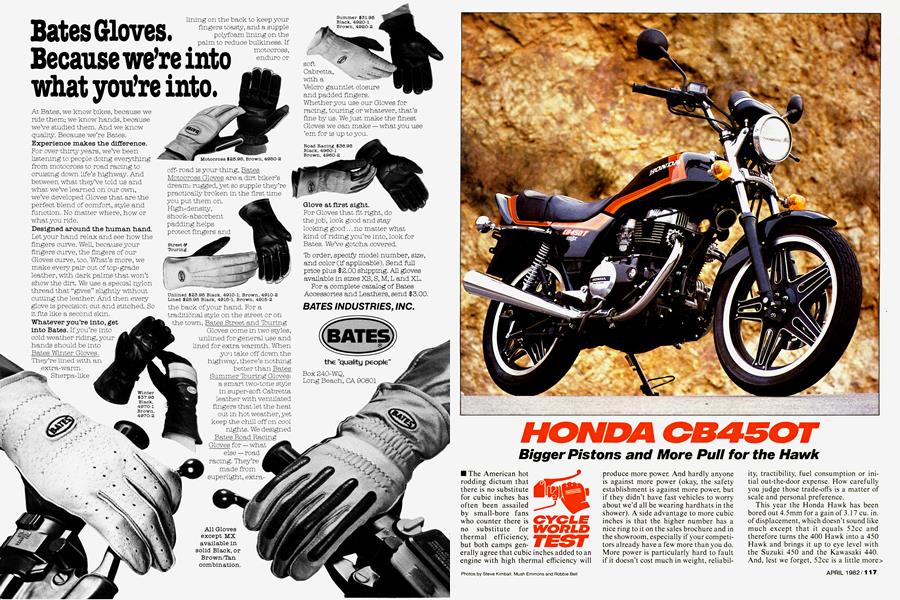

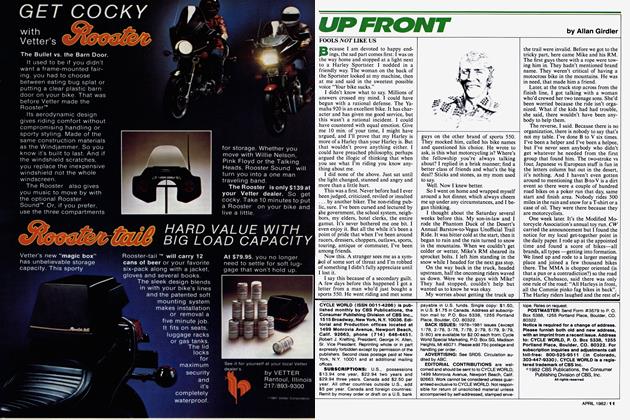

HONDA CB450T

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Bigger Pistons and More Pull for the Hawk

The American hot rodding dictum that there is no substitute for cubic inches has often been assailed by small-bore fans who counter there is no substitute for thermal efficiency, but both camps generally agree that cubic inches added to an engine with high thermal efficiency will

produce more power. And hardly anyone is against more power (okay, the safety establishment is against more power, but if they didn't have fast vehicles to worry about we'd all be wearing hardhats in the shower). A side advantage to more cubic inches is that the higher number has a nice ring to it on the sales brochure and in the showroom, especially if your competi tors already have a few more than you do. More power is particularly hard to fault if it doesn't cost much in weight, reliabil

ity, tractibility, fuel consumption or initial out-the-door expense. How carefully you judge those trade-offs is a matter of scale and personal preference.

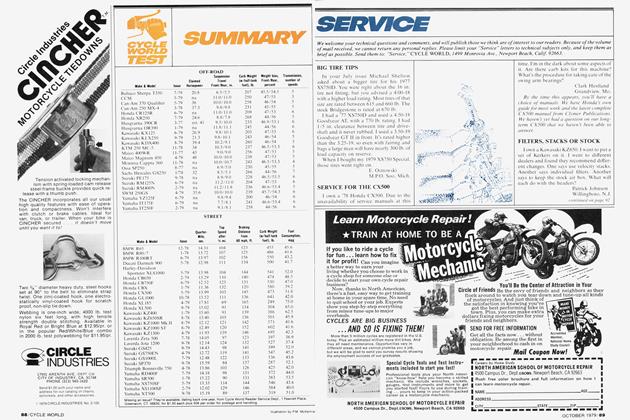

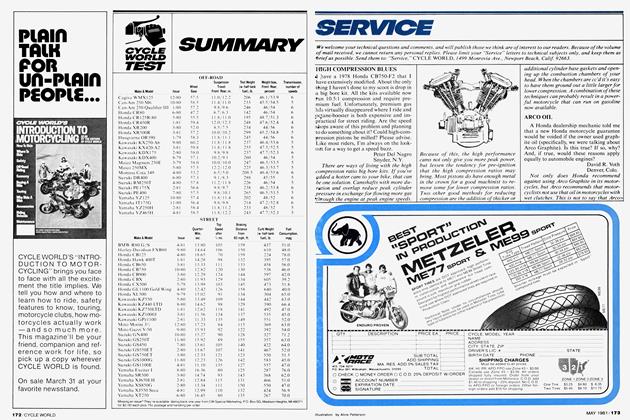

This year the Honda Hawk has been bored out 4.5mm for a gain of 3.17 cu. in. of displacement, which doesn’t sound like much except that it equals 52cc and therefore turns the 400 Hawk into a 450 Hawk and brings it up to eye level with the Suzuki 450 and the Kawasaki 440. And, lest we forget, 52cc is a little more> than the total displacement of the first Honda many of us rode. The bigger Hawk is now faster and quicker, turning the quarter mile in 13.78 sec. at 91.74 mph compared with 14.28 sec. at 88.23 mph on the ’81 400T. Honda claims no increase in peak power over last year’s rating of 39 bhp, but tells us the powerband has been both widened and lowered. Our own drag strip testing bears that out, as does seat-of-the-pants calculation, showing a good increase in mid-range acceleration. Top speed in the half mile is now 101 mph rather than 98 mph.

So the extra 52cc, along with a few other internal tricks, have indeed done their work. The bigger engine is faster. Now the trade-off. Power is seldom free, of course, and there are some entries to be made on the debit side of the ledger.

First, the 1982 Hawk weighs 1 lb. (yes, one pound) more than last year's model. Not bad. Then there’s fuel consumption. On our town-and-country mileage loop we recorded a drop of 4 mpg, down to 53 mpg from 57 mpg on the old 400. This slight decrease in mileage is only to be expected, though we’ve been spoiled these past few years as larger and faster bikes have been getting increasingly better mileage. That trend may be reaching its practical limit with current engine designs, however, unless bikes get radically lighter or we are willing to accept horsepower reductions, and we most certainly

are not. Anyway, 53 mpg is commendable for any machine, and moreso for one that does the quarter mile in less than 14 sec.

Slightly more severe than the mileage decrease is the price increase. The Hawk now lists for $1998, up $100 from the ’81 Hawk and its $1898 price tag. The day is gone, however, when we can measure price increases against improved quality and better designs. All price increases are now blamed on World Inflation, so we never know if new expensive products are better or worse than the old cheap ones. Anyway, the Hawk is up in price and those who gasped when the light sport/ commuter Twins first toppled over the $1000 mark will now note they are pushing at the $2000 limit. All it takes, of course, is a $ 10,000 economy car to make that price seem more reasonable.

Purchase price and fuel consumption are noticed most at the billfold or checkbook, but changes in power and tractibility surface only during the first test ride. And the most noticeable change in the 450 Hawk, along with its very brisk performance, is a new stumble and hesitation when the throttle is twisted below about 5000 rpm. The new Hawk uses the same twin 30mm Keihin carbs found on the ’81, and changes in intake velocity and volume with the larger cylinder bores have made throttle response slightly less agreeable. Under full throttle acceleration or at high rpm the carbs work flawlessly, but when cruising around town or in traffic, the engine has a lean, hunting feel, as though the bike is about to run

out of gas. Twisting the throttle produces a momentary feeling like that of turbo lag, but without the turbo. This condition is not serious enough to take the fun out of riding the Hawk, but it is a minor annoyance on what is otherwise a very hardcharging 450 Twin.

In boosting performance Honda has done more than install larger pistons to push the bike up to 450cc, as all increases in displacement and torque have repercussions throughout the drive train. Connecting rods are now made of higher quality steel, the same grade as that used on CBX rods. The outer diameter of the piston pins has been fattened 1mm and the inside diameter of each pin has been reduced 1mm, effectively making a 2mm thicker piston pin to accommodate the lower, heavier pulses of the engine’s relocated powerband. At the upper end, cam profile and valve sizes go unchanged, though the rocker arm bosses have been modified for better oil flow. The pistons themselves, in addition to being 4.5mm wider in diameter, have new, thinner three-piece oil control rings and the same compression rings as those used on the GL1000. The compression ratio has been dropped, however, from 9.3 to 9.1:1.

Other engine changes have been made more to improve noise control or ease maintenance than to beef it up for increased power. The clutch housing was changed last year, with springs replacing rubber dampers that used to compress with age and cause clutch rattle, and this year Honda has developed a more accurate machining technique for teeth on the primary gears to help reduce mechanical noise. Transmission gears are now given a liquid nitrogen hardening treatment that is supposed to make them more durable. People who do upper end service work on the Hawk will be glad to hear the cam chain adjuster has also been redesigned, so it can be removed without the cases being split.

The Hawk has always used what Honda calls a Power Chamber in the exhaust system, a sort of pre-muffler beneath the engine and ahead of the twin mufflers. Where the exhaust pipes from the engine enter this box they have now been extended farther across the centerline of the chamber, a change Honda says has a great deal to do with the new power characteristics of the engine.

This change in the exhaust system, along with the increased bore size, has lowered the power peak from 9500 on the old Hawk to 8500 rpm on the new 450. As mentioned, peak power has remained the same, but the dyno now shows a torque increase at low and mid engine speeds. To take advantage of that powerband, the gearing has been changed. The primary gear ratio has been numerically lowered from 3.125:1 to 2.960:1. Internal transmission ratios have all remained the same, except for a lower first, now a 2.857:1 rather than a 2.733:1. For a higher final drive ratio, one tooth has been dropped from the rearsprocket, the 450 rear having 36 teeth instead of 37. The net effect of all this juggling is higher overall gearing, a direction Honda is heading with many of its 1982 models. The CB450T now cruises down the highway at 60 mph turning 5043 rpm, while last year’s CB400T was revving to 5455 at the same speed. Other 450 models, except for the automatic, will have an even taller top gear which, when engaged, will blush through an instrument panel light that says “Overdrive.” This is not a real overdrive, of course, but merely a higher top gear.

The Hawk engine is painted flat black this year, so unless you look closely it’s easy to miss another external change in the engine. The Hawk now carries an oil cooler at the front of the sump, the same cooler previously used only on the Hawk automatic transmission models. This is not a radiator type oil cooler, but a sort of heavily finned second sump that aids in cooling the oil while also adding just over a pint of extra oil to the sump capacity.

Honda last year revamped the brakes on the Hawk and several other models, going to a dual piston brake caliper and longer, narrower brake pads that exert more pressure farther out on the caliper for better mechanical advantage. The brakes are unchanged this year, and still provide a solid, easily controlled feel and good stopping power. There is no feeling of caliper flex or vagueness at the lever,

just reassuring control. The rear drum, finned like that on the CX500, also works well.

One thing that has changed for the better is transmission feel. Last year’s 400 was a little stiff and notchy and required high pedal effort during rapid downshifts. Some riders also had problems with the trans jumping back out of gear if shifts were made hastily or without firm foot action. This year's transmission worked well enough that it almost escaped notice or comment. It shifts easily and smoothly.

Though it has the look and sound of an everyday commuter bike powerplant, the Hawk’s motor makes a respectable amount of power for a 450 sohc Twin, as it did when it was a 400 sohc Twin. Its bore and stroke configuration, highly oversquare before, is now more oversquare than ever at 75 X 50.6mm. Twins can do this sort of thing without running into engine width problems, as long as

they are able to breathe well and propagate flame without detonation ills. The Hawk breathes through three valves per cylinder, two intakes and one exhaust, operated by a single overhead cam. The intakes are opened and closed by a single forked rocker arm, each fork with its own threaded valve adjuster. Another, slightly offset rocker arm, runs the single exhaust valve. The two intake valves allow better breathing on a wide cylinder bore such as the Hawk’s, providing greater intake area than a single valve and less individual reciprocating weight to keep up with high engine revs.

The combustion chambers are of the wedged, pentroof variety, and the pistons are mildly domed with small valve relief pockets. The spark plug is offset in the combustion chamber. This setup provides good combustion characteristics, as we were unable to make the Hawk engine ping, even with some fairly low-grade fuel in the tank. At the bottom end the> Hawk uses a 360° crank, both pistons rising and falling at the same time and fired on alternate strokes. Twin counterbalancers, chain driven, rotate at the front of the engine to smooth out the normal vertical Twin vibrations and they do the job well. The engine is smooth running, without any abrasive vibration periods showing up on the rev band. The plugs are fired by a breakerless CDI system.

The Hawk uses a pair of 30mm Keihin CVs for carbs. The choke is cable operated and the knob is located above the handlebar clamps. The 450 starts immediately on full choke and runs at a reasonable fast idle without letting the revs shoot skyward. The bike can be ridden away without a lengthy warmup and runs very well, provided plenty of choke is used. As exhaust notes go, the Hawk’s is not a real crowd pleaser when the engine „ is first fired. We were told when the first CBX was introduced that Honda engineers had recorded the sound of a Phantom jet and then tried to duplicate that sound in the bike’s exhaust note. In the Hawk’s case they may have forgotten to start the airplane engine and accidentally recorded the sound of the airport lawnmower instead, because no motorcycle made sounds more like a Toro or a Lawn Boy than the Hawk at fast idle. It makes us long for more of the deep motorcyclish sound of the original Honda CB450, but without that bike’s vibration and slower acceleration, of course.

The engine requires a longer than usual warmup period before the choke can be pushed all the way off for normal running. As mentioned earlier, normal running is not all that good at low throttle openings, and it makes the rider wish he could pull the choke on and go through warmup all over again. At highway speeds where wind resistance keeps the engine under load, during full acceleration, or any other time throttle settings are reasonably high, the engine performs beautifully. But cruising around town the engine displays a streak of lean surge and hesitation.

This is unfortunate, because one of the nicest things about the Hawk, and most other mid-sized Twins, is that it makes a light, maneuverable vehicle for short trips and errands. But throttle response keeps the Hawk from being a completely satisfying town bike.

Where the Hawk really comes into its own is out on the highway, or, better yet, out on the twisting highway. The 400 Hawk was a fast, good handling bike on the racetrack or on the curving mountain road, and now the 450 Hawk is a faster good handling bike. On a fast run up one of our favorite canyon roads, one rider reported he had to keep looking down at the engine between corners to make sure he was really on a 450 Twin. The bike pulls hard out of corners and keeps pulling hard all the way up to its 9500 rpm redline.

The Hawk is one of those bikes that make it easy to keep up with friends who are riding larger, more powerful bikes. They’ll have to ride very hard indeed to leave you behind on an unfamiliar curving road because the light weight and agility of the Hawk, along with its good power and rock stable handling, inspire an instant confidence that makes it easy to ride fast. Steering is neutral, neither skitterishly quick nor resistant to steering input, and midcorner changes of line for sandpatches, cars and road rocks are as easy as thinking about them. As speeds increase, the workaday commuter personality of the Hawk recedes and the bike transforms itself into a satisfying, accurate tool for going fast.

Honda has made numerous improvements in the Hawk’s suspension since the bike’s introduction, and last year they upgraded the rear shocks, added air caps to the front forks and installed a beefier set of triple clamps, all of which added a feeling of tightness and solidness to a bike that handled pretty well to begin with. The air caps on the forks have a crossover tube to make equal adjustment easy (and remotely possible) with a standard recommended pressure of 11 psi. At the lowest pressures the forks still work well, without undue spring sack or softness, but at 11 to 14 psi the bike picks up a bit more cornering clearance and the front end has a tauter feel, particularly under hard braking. The rear shocks have no adjustment for damping, but provide the usual five-way spring preload adjustment. Honda calls these VHD (Variable Hydraulic Damping) shocks, variable meaning they have a blow-off valve to prevent the shocks from going into the pogo-mode when they become overheated and overworked.

Though decked out and trimmed as a sport model, the 450 Hawk still comes to us with an essentially middle-of-the-road set of handlebars and footpegs. Most of the other manufacturers are now providing straight sport models with tucked-in footpegs and slightly lower bars, while the Hawk has retained its high, wide bars and far forward peg position. Honda does a lot of market research on this sort of thing, and it may be that the Hawk sells to such a wide cross-section of the market on good looks and reputation alone, that narrowing any of their 450 models to a straight sport riding market would lose sales. For whatever reason, the riding

position on the Hawk is of the all-purpose compromise school, so those who want to go peg dragging can install rearsets and lower bars while riders who want to commute or tour can install the appropriate fairing and sit upright with full wind protection. As it is now set up, the footpegs are positioned in a fairly wide stance right alongside the engine cases, so most riders will find their knees farther apart than the width of the tank.

The tank and seat are both unchanged for ’82. The seat is as hard as last year’s, with better padding for the passenger than for the rider. It is a sport style saddle that makes it easy to move around on the bike, but will cause butt fatigue if two consecutive tanks of gas are burned without a restaurant meal or a day hike between them. Not an intolerable seat by any means, but firm. The tank continues to hold 3.4 gal. of gas and will go about 145 mi. before reserve. The tank petcock is the traditional on-off-reserve style with no vacuum valve to shut it off when the engine is stopped, which for most of us means one less hose to fiddle with while removing the tank for servicing. The gas cap is standard Honda childproof; a locking arm over a one-way screw cap.

Instrument lighting on the 450 is as good as it was last year, which is very good. The tach and speedometer faces are lighted from behind through translucent dials so glare is low and readability high. All the Hawk’s controls, clutch, brake lever, switches, etc. are smooth working and have a slick, well-finished feel.

Now that the Hawk has turned itself into a 450, direct comparisons can more fairly be made with the Kawasaki 440 and Suzuki 450, in both price and performance. In performance the Hawk is a bit quicker and faster than the last Kawasaki 440 we tested, though that was an LTD model and the picture may change when we get the 1982 belt drive sport version, the KZ440G. And the Hawk is slower than the Suzuki GS450S we tested in 1980, a bike that turned a 13.61 sec., 94.93 quarter mile. The Suzuki has a more powerful, twin cam engine, feels a bit bigger and is not quite as simple to maintain as the Hawk, though it needs very little maintenance. The Hawk, however, is a better handling bike than the last Suzuki 450 we rode. We haven’t yet tested the new Yamaha 400 Seca, so it remains to be seen where that fits in the picture. With its latest price increase, the Hawk is now the most expensive of the Japanese sporting 450s, listing at $100 more than the 1982 Suzuki GS450E and $200 more than the belt drive KZ440G.

The 400-450 market is highly competitive (as are most of the other markets) and it is a class where price is often a very important consideration for the young or first-time buyer. As the prices of labor, materials, energy, etc. continue to climb it has to be a continual struggle for manufacturers to offer bikes in this class at prices buyers are willing to pay. The Hawk is an excellent example of careful engineering that builds a bike to a price. It is strong, efficient and attractive, and yet a careful examination of pieces and components reveals that nothing has been wasted. Pieces are no thicker and plating is no heavier than it has to be. While the design and function have advanced tremendously compared with some of the older Twins, the bike leaves you with a feeling that less time and expense has gone into its manufacture compared with, say, the earlier CB350 and CB450 Twins, or the 400F. The lavishing of labor and materials on motorcycles has no doubt moved up the displacement scale a bit.

But then motorcycle magazines tend to harp on function whenever possible, and in that regard a bike like the CB450T is a far better machine than most of its predecessors. It is faster, smoother, quieter, more economical, better handling and just as much fun to ride. And in the world of real value and the shrunken dollar, still a bargain. 13

HONDA CB450T

$1998

View Full Issue

View Full Issue