BMW R100S

New Bikes Don't Get Much Newer Than This One

CYCLE WORLD TEST

As your heavy duty media events go, the uncrating of a new BMW motorcycle doesn’t rate very high. There are exceptions. One that burns vividly in our minds is a recent uncrating we were invited to attend at me western headquarters of Butler & Smith in Compton, California.

Butler & Smith is BMW's U.S. distributor, and its principals are an increasingly skeptical view of how test bikes are headed out to the motorcycle press. Without naming names or frothing at the mouth, our friend Helmut Kern at Butler & Smith West suggests that at least some of the new machines doled out are somewhat peppier thazi their production counter-parts. thanks to loving massage applied by the various public relations departments.

K~aIs~notes that s~4est massage is a BMW practice. The hike, you see te~An the magazine is the same bike you n'buy from your Uealer. he says.

By way of dra;atH~his c~flte~tiQns. Kern made us n: Com~to~h~ warehouse, pick o ny bif~r test. We11 uncraté it. set4it up ide~t out of the w~jehause. k'e~veren co~ced~ ...~mandsof we occasion~F vith~~-production bikes for testi~f we wéi~e to wait for the first shipment of a new production model, we'd find ourselves publishing tests several months after the bike hit the market. Gen erally speaking~ we've encountered fe~ inconsistencies between these pre-prod uc tion models and the first of the production i~ines. Most of the differences are aca demic. Moreover, a good many test bikes that come our way could use. some massag ing. It's not at all uncommon for a test bike to arrive in less-than-perfect~ running order-hardly a syrnptorp~~ of the machine carefully prep4red to create Great Expectations

But we nevertheless like Helmut’s way of doing things, and the prospect of a mintfresh Beemer to run up from zero mileage is something few, of us encounter. Because there was1 also the prospect of a slightly new model to scrutinize, we thought you might like to share the w'hole experience with us.

The experience began one rainy March morning when we arrived at Butler & Smith’s hangar-size facilities in Compton. The inside of this enormous barn is a BMW lover’s dream come true-crate upon crate upon crate of new' motorcycles, stacked right up to the rafters. How often do you see one R100RS let alone towers of

four stacked side by side? Kern told us his operation. which serves nine western states, moves about 2000 bikes per year. The rest of BMW's U.S. distribution is handled through Butler & Sm East. in Norwood, N.J.

We were usj~•ered~to the shipping! receiving `~re Kernsh~' a truck size~~ er-still sealed_wa~1n& • were crate~ containing new bikes—30 of them—and we were invited to take our pick. Can you imagine that, BMW lovers? A guy with the power to make it happen leads you up to this truckload of absolute virgin Beemers and says, “Help yourself.” Even though we knew possession was only temporary, it was nevertheless a special moment.

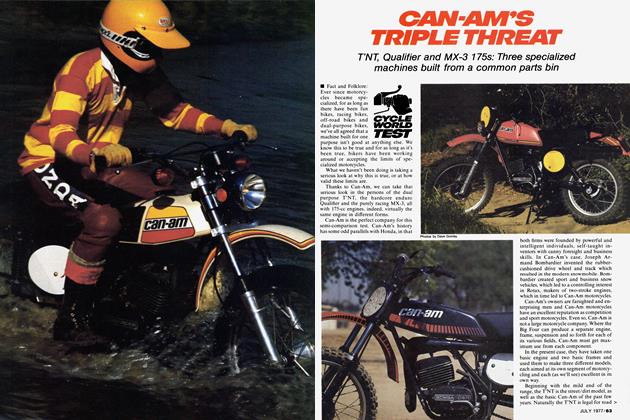

Our choice wound up being a red smoke RIOOS. As you will note from the photos, this is a new version of the sports bike that entered the market five years ago. When the first R90S hit the streets, it came with a bikini fairing and low, narrow bars. It wasn’t exactly cafe, but it certainly said sports. This treatment was continued w hen the model became the RIOOS, and is still offered. However, the bike you’re looking at here is also an RIOOS. It differs from its sporty stablemate principally in its use of standard BMW touring handlebars and the absence of a fairing. As you might expect of a company that regards change with the same caution one accords investment in foreign oil firms, BMW has a reason for this new integer between the R100/7 and the sports RIOOS. But let us amplify on that theme later, once we’ve got the bike off the truck.

Our motorcycle was about halfway back in the container, and within minutes Kern and right-hand man John Heibler were set to hoist out of the crate. New BMWs r ^ arrive completely assembled. All that’s needed for setup is addition of various liquids (there’s only about a quart of oil in the engine); a check of timing and valve clearances; removal of various protective films, such as the material that covers the brake discs; and a battery charge.

It’s a fine thing to straddle a bike that shows all zeroes on its odometer and trip counter. New BMWs leave the assembly line with 99,999 miles showing on the clock. Then they’re equipped with a small gas and battery power pack for a one-mile test ride, which zeroes the odo. If everything checks out, the new tank goes on, the new battery goes in and the new Beemer goes into its box.

Running in a zero-mileage BMW is something that’s outside the experience of our test staff. The last one that came our way (the R80, tested in January) was already well broken in, and thus conveyed the usual BMW riding impressions—cushy and supple. But a BMW with no miles isn’t quite the same creature. The forks are stiff, ditto the clutch, the front brakes have almost no power and the engine wants to idle at about 2500 rpm.

We began to develop proprietarial anxieties, which led to poor John fielding a large number of telephone calls.

“John, the BMW doesn’t want to idle once it’s warmed up.”

“Don’t worry about it,” he said. “It’s

new. It’ll be OK.”

“John, we’re getting a lot of bluing on the head pipes. They’re almost purple already, and we’ve only ridden the bike a couple hundred miles.”

“Don’t worry about it. Those pipes are simply gonna blue. It’ll be OK.”

“John, the forks don’t work.”

“Don’t worry. It takes a few hundred miles for ’em to smooth out.”

As you might expect. John was right. When the bike was ready ‘

for its first service—600 miles— it was already showing signs of loosening up. The brakes were bedded in, the engine revved much more freely and idled comfortably at about 950 and the forks were beginning to behave more like the BMW forks of our collective memory: effortlessly. Maybe all the Beemer freaks are right when they say these things don’t even start to run until they’re 10,000 miles old.

This new edition of the R100S probably won’t appeal to riders who go for the jazzier sports setup. If you like the cafe crouch, you’re better off with the • m original version of this

model, an

opinion vind 1cated by a pal of ours who owns a two-yearold RIOOS. Although he liked the handling qualities of the new bike, which are improved by the cast wheels, he couldn't shake the conviction that high bars and no fairing on an R 100S constitute some sort of crime against nature.

BMW R100S

$4800

ACCELERATION / ENGINE AND ROAD SPEEDS

FRONT FORKS

BMW leading-axle fork

Fork travel....................................7.2 in.

Engagement................................6.3 in.

Spring rate........................18/77 lb./in.

Compression damping force 12 lb.

Rebound damping force..............19 lb.

Static seal friction........................18 lb.

Stanchion tube diameter ..........36 mm

Forks on late Beemers are of one basic design, with slight variations between different models. The damping on this dual-disc S model is the same as on the RS, but spring rates differ. The initial rate is softer, but the secondary rate, which is effective over the last 1 Vfe in. of travel, is much higher. Seal friction, high because of the bike’s newness, decreases with additional miles, yielding a softer ride.

REAR SHOCKS

DISPLACEMENT

Boge shock, non-rebuildable

Shock travel ................................3.9 in.

Wheel travel ............................. 5.0 in.

Spring rate......................95/225 lb./in.

Compression damping force 8 lb.

Rebound damping force..............82 lb.

The Boge dampers and springs used on the S are the same as those used on the RS. The units are firm for control, yet not harsh. The resulting ride is comfortable, yet offers a high degree of control when the situation demands.

Tests performed at Number 1 Products

Well then, why a touring model when there’s already a lOOOcc touring model — the R100/7—in the lineup? Because touring gear is heavy, and for some riders the R100/7’s 60 bhp isn’t enough. To keep these riders from slipping away to some other make—and to lure other new riders into Beemerdom—BMW has wrapped the RIOOS powerplant in a packaged designed to lug all the paraphernalia that makes touring a civilized pastime.

The difference between the 100/7 and 100/S engines lies in carburetion (32mm CV Bings for the former. 40mm for the S); compression ratio (9.0:1 vs 9.5:1); and valve sizes (42mm intake, 40 exhaust for the 100/7. 44 and 40 for the S). The differences are worth five horsepower and a bit more torque—the 100/7 generates 54.2 ft. lb. at 4000 rpm, the S 55.7 at 5500 rpm.

The touring version of the S gets the same instrumentation as the sports model—speedo, tach. clock and voltmeter—but these are laid out in a row, to allow for the addition of a touring fairing. In the sports model, the clock and voltmeter are mounted in the fairing, above tach and speedo.

The 1978 model year embodies a number of improvements to the BMW line, detailed in our test of the R80. To review: All Beemers have been given new handgrips; slick new signal repeaters that cease their bleating when the clutch is disengaged or the gearbox is in neutral: light green numerals on the instrument faces for easier night reading; new electronic tachometers; single-key systems —one key works tank, ignition, steering and seat locks, and new gearshift linkage. The latter is an especially welcome addition to the BMW’s running gear inventory. Pivoting at the left-side footpeg, it provides much more positive shifting than previous setups. particularly in downshifts.

Special new touches to the S and RS models are cable locks that stow inside the top frame tube, electric quartz clocks, dual drilled front discs, rear discs and handsome cast alloy w heels.

BMW's flat Tw in, shaft drive and double wall, double cradle frame are hardly unknown to cycledom, having stayed prettv much the same since 1923. The double tubing, employed in the top frame section. > and extra gusseting in the rear sub-frame are about the only recent improvements in this area.

This edition of the engine, which is about as big as the Twin is likely to get in its current configuration, packs plenty of grunt although it isn’t what you’d call quick, measured against the current crop of lOOOcc street wailers. Our bike’s quarter-mile times were hampered a trifle by the engine’s newness, but the best numbers we’ve heard on lOOOcc Beemers run in the very high 12s. Light-to-light snort isn't part of this machine’s act, partly because of the dry, single-disc automotive-type clutch, which is manageable and progressive but doesn’t like abuse, mostly because drag racing isn’t what Beemers are born to do. What they are good for is the long haul, and in this area they continue to be unique. The big Twin delivers power all through its rev range, but is happiest above 3000 rpm, particularly in fourth and fifth gear. Vibrations also disappear once the tach needle hits 3000, and the engine is smooth right up to the 7600-rpm redline. (Our friend’s R100S, with 6000 miles on the clock, revs freely—and quickly—up to 8000 rpm without strain.) Below 3000 the engine is a trifle lumpy.

Naturally, there’s a price to be paid for the additional performance of the S version of the engine. The 40mm Bings move more fuel than the 32s, and the best mileage figure we obtained was 39.3 mpg. However, this is another performance area that should improve as the engine loosens up.

Besides handlebars and instrument layout, this bike differs from the older sports S model iri that there’s a nifty document compartment built into the front part of the saddle. While this little niche is certain to be safe from the elements, we feel it interferes somewhat with rider comfort. We found the forward part of the saddle to be somewhat firmer than the older 100S. It stops short of actual discomfort, but it does begin to intrude on your consciousness after 100 miles or so. The passenger’s portion of the saddle doesn’t suffer from this, and with the Boge shocks set up to max pre-load two-up riding is smooth.

Up front we’ve substituted R100RS fork springs for the stock units, because we plan to have a fairing installed on the bike. We find that the RS springs reduce the Beemer’s characteristic dive under hard braking, and produce a somewhat firmer ride, just right for those of the barnstorming persuasion. However, in box-stock form the bike works well enough. Like all the members of its tribe, it’s stable, predictable and long on cornering clearance.

Braking is an especially strong point. The new rear disc, by Brembo, shows little tendency to lock and the front pair, once bedded in, have more than enough power to handle any stopping situation. The key to their excellence lies in their controllability, and this factor, combined with their power, puts them very close to the top

of the superbike class.

The Metzeler tires were developed specifically for this machine and seemed well suited to it. We’ve heard complaints about their being a trifle hard for really spirited riding, but the stick seemed good during a couple of canyon excursions. Some S models come equipped with Continentals, and these are preferred by our friend with the two-year-old model. Whether you wind up with Metzelers or Contis seems to be purely a matter of chance, but it isn’t something to worry about.

As noted, we have further plans for this bike. Because the idea is to buy (for $800 over the 100/7) a little more power to handle fairing, luggage, tank bag, etc. we’ll be assessing the bike with these items in

place. This will give us an opportunity to evaluate the Luftmeister touring fairing as well, and. of course, to spend more time with this new Beemer.

We’re looking forward to it. Like fine wines, BMW motorcycles are an acquired taste. To carry the parallel a little further they’re at their best with a little aging. They look great right out of the crate—the red smoke finish is the best BMW color to come down the road in quite awhile—and the concern with quality is visible everywhere. But full appreciation of their excellence doesn’t really set in until rider and bike have done a few thousand miles together. What this process almost invariably produces is converts, and we’re willing to keep the faith. Q

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCarte Blanche

June 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1978 -

Roundup

RoundupRoundup

June 1978 By Tim Barela -

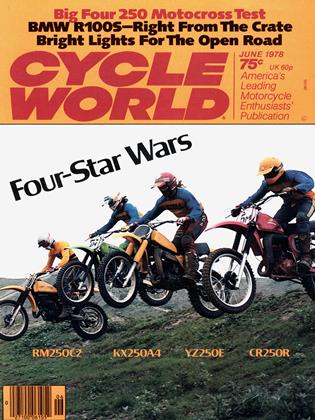

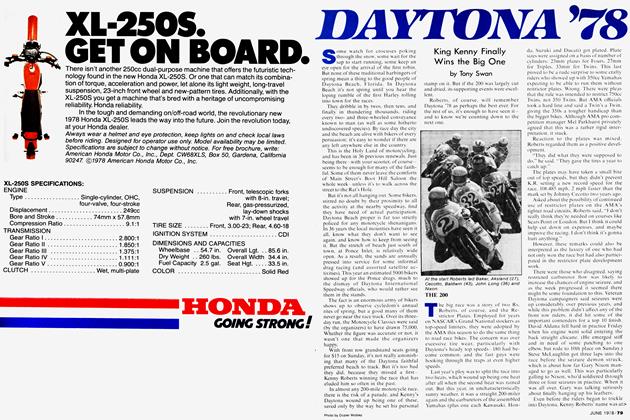

Competition

CompetitionDaytona '78

June 1978 By Allan Girdler, Tony Swan -

Features

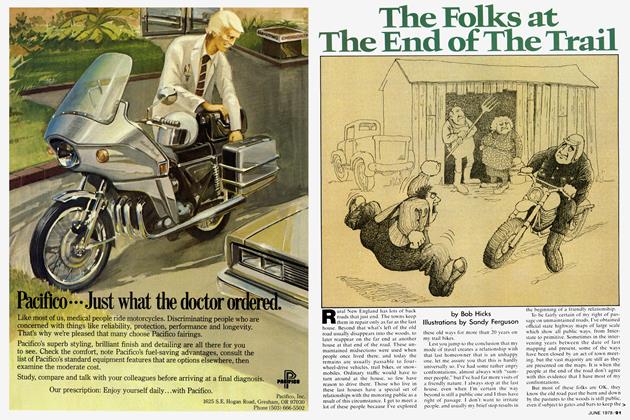

FeaturesThe Folks At the End of the Trail

June 1978 By Bob Hicks -

Competition

CompetitionAn Incomplete Guide To Special Events

June 1978