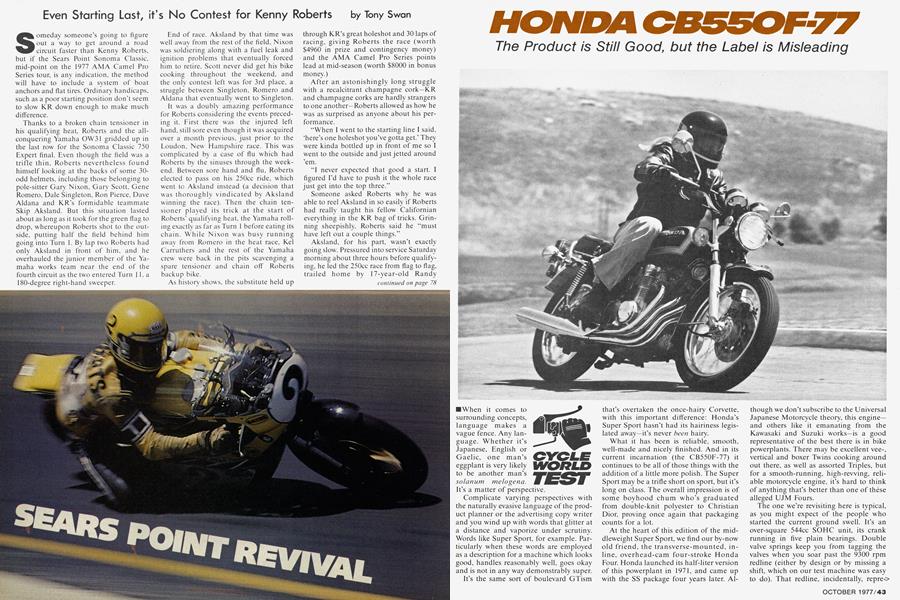

HONDA CB550F-77

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Product is Still Good, but the Label is Misleading

When it comes to surrounding concepts, language makes a vague fence. Any language. Whether it’s Japanese, English or Gaelic, one man’s eggplant is very likely to be another man’s solanum melogena. It’s a matter of perspective.

Complicate varying perspectives with the naturally evasive language of the product planner or the advertising copy writer and you wind up with words that glitter at a distance and vaporize under scrutiny. Words like Super Sport, for example. Particularly when these words are employed as a description for a machine which looks good, handles reasonably well, goes okay and is not in any way demonstrably super.

It’s the same sort of boulevard GTism that’s overtaken the once-hairy Corvette, with this important difference: Honda’s Super Sport hasn’t had its hairiness legislated away—it’s never been hairy.

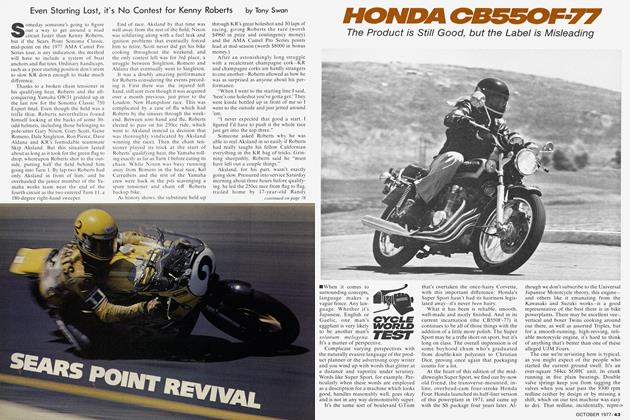

What it has been is reliable, smooth, well-made and nicely finished. And in its current incarnation (the CB550F-77) it continues to be all of those things with the addition of a little more polish. The Super Sport may be a trifle short on sport, but it’s long on class. The overall impression is of some boyhood chum who’s graduated from double-knit polyester to Christian Dior, proving once again that packaging counts for a lot.

At the heart of this edition of the middleweight Super Sport, we find our by-now old friend, the transverse-mounted, inline, overhead-cam four-stroke Honda Four. Honda launched its half-liter version of this powerplant in 1971, and came up with the SS package four years later. Although we don’t subscribe to the Universal Japanese Motorcycle theory, this engine— and others like it emanating from the Kawasaki and Suzuki works—is a good representative of the best there is in bike powerplants. There may be excellent vee-, vertical and boxer Twins cooking around out there, as well as assorted Triples, but for a smooth-running, high-revving, reliable motorcycle engine, it’s hard to think of anything that’s better than one of thèse alleged UJM Fours.

The one we’re revisiting here is typical, as you might expect of the people who started the current ground swell. It’s an over-square 544cc SOHC unit, its crank running in five plain bearings. Double valve springs keep you from tagging the valves when you soar past the 9300 rpm redline (either by design or by missing a shift, which on our test machine was easy to do). That redline, incidentally, repre-> sents a 100 rpm gain over our last visit with this bike (August 1975). Compression has decreased slightly, from 9.1:1 to 9.0:1, although this is hardly enough to account for the performance difference between this bike and its 1975 predecessor.

HONDA CB550F-77

$1730

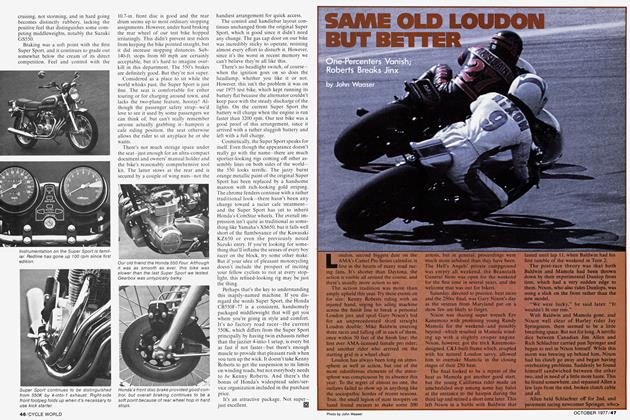

With a 160 lb. rider aboard, the 550’s forks settle nearly 2 inches, giving an effective travel of 2.5 inches. Despite proper damping rates, this lack of travel severely compromises handling. Installing 1-in.to 11/2-in. preload spacer above each fork spring will restore ride height and improve handling.

Spring and shock rates are close to optimum for a bike of the Super Sport’s demeanor. Performance-oriented riders or avid tourers, before considering installing an appropriate accessory shock, should first correct the fork preload inadequacy. If not done, a different shock could conceivably aggravate the situation.

Tests performed at Number One Products

Our 1975 Super Sport was substantially more potent, putting up a 13.76-second quarter-mile time and hitting 96.46 mph in the process. As the data panel indicates, our new machine didn’t do nearly as well. The results were something of a surprise, since the engine seemed to pull well enough, delivering what seemed to be plenty of punch through the multi-disc clutch, the latter being a good representative of Japanese clutches in terms of easy manageability and engagement subtlety. But even discounting our times by a tenth or two for strong headwinds during a long afternoon at Orange County International Raceway, we still wound up with runs that are disappointing if you take the words Super Sport seriously.

We didn't experience it at the drag strip or during a visit to the Willow Springs road racing course, but in street and highway riding we found that this engine exhibited a strong tendency to bog between 4700 and 5500 rpm, particularly in top gear. This is awkward, since these rev ranges represent highway cruising speeds. Sub-5000 rpm sluggishness was a failing in our 1975 Super Sport as well, although it wasn’t so pronounced as in the current example.

Like most of the fast-turning Fours, the 550 exhibits a substantial thirst, particularly when it’s being driven hard. In combined street and highway use we recorded 41 mpg. This figure fell 10 mpg when we were wringing the bike out at the strip and Willow Springs.

The gear box on our bike wasn’t particularly agreeable, either. Upshifting required a firm toe, and there was a pronounced stop between first and second. Finding neutral was far too easy, particularly if the first-to-second shift was hurried. We put this down to the balkiness of this particular transmission, since most Honda gear boxes are much more cooperative.

However, the Super Sport’s driveline play is definitely characteristic of the make—nothing much has changed on that score, really, since the introduction of the endless drive chain. Throttle response, too, is tricky. It’s hard to get throttle feathering in tricky cornering situations—it’s either power on or power off, which is a severe limitation to spirited riding.

The rubber gaiters that covered the Showa forks of the original Super Sport have long since disappeared, but the bike’s handling remains much the same: fine for most ordinary applications, adequate for spirited tour riding, twitchy for anything that smacks of wild-eyed peg scraping or tight-lipped late braking. If you’re into these pastimes, you’re likely to find the Super Sport trade name rather limited on content.

This is not to imply that the bike is in any way unpleasant to ride. Quite the contrary. Ride and handling are both carefully engineered to what Honda perceives to be the broadest possible market. After all, how many riders really need stiffer suspension all around? And how many really want to live with the harsher ride that accompanies a performance-oriented selection of springs and shocks. Honda’s guess is not many, and the success of the Super Sport is vindication for that guess.

The Super Sport’s suspension package puts us in mind of one of the automotive Super Sports, offered in the past by Chevrolet. It was smooth, it was effortless, and it was about as sporty as oatmeal. The CB550F-77 certainly isn’t the undersprung soft rider that Chevy’s old Super Sport was, but it’s intended to perform similarly in the essentials of street cruising—and does. Its front suspension is pleasantly supple, and does an excellent job of gobbling up expansion joints, lane marker bumps and the like. On our favorite chunk of ride-testing freeway—a section of the Santa Ana (Interstate 5) that seems to have been finished off by a former porpoise trainer—the 550 behaved like a larger bike, making easy work of the endless ferroconcrete swells. But on really heavy duty bumps, the suspension will bottom, giving the rider a nasty jolt and creating considerable mischief with incidentals such as cornering lines.

The limiting factor is suspension travel. Honda claims 4.8 in. in front, 3.5 at the rear. Our measurements show 4.4 and 3.2 (see suspension panel), and whether you use our figures or theirs, neither works out to be enough. This setup is intended for> cruising, not storming, and in hard going becomes distinctly rubbery, lacking the positive feel that distinguishes some competing middleweights, notably the Suzuki GS550.

Braking was a soft point with the first Super Sport, and it continues to grade out somewhat below the cream of its direct competition. Feel and control with the 10.7-in. front disc is good and the rear drum seems up to most ordinary stopping assignments. However, under hard braking the rear wheel of our test bike hopped irritatingly. This didn’t prevent test riders from keeping the bike pointed straight, but it did increase stopping distances. Sub140-ft. stops from 60 mph are certainly acceptable, but it’s hard to imagine overkill in this department. The 550’s brakes are definitely good. But they’re not super.

Considered as a place to sit while the world whisks past, the Super Sport is just fine. The seat is comfortable for either touring or for charging around town, and lacks the two-plane feature, hooray! Although the passenger safety strap—we’d love to see it used by some passengers we can think of, but can’t really remember anyone actually grabbing it—hampers a cafe riding position, the seat otherwise allows the rider to sit anyplace he or she wants.

There’s not much storage space under the seat—just enough for an ultra-compact document and owners’ manual holder and the bike’s reasonably comprehensive tool kit. The latter stows at the rear and is secured by a couple of wing nuts—not the handiest arrangement for quick access.

The control and handlebar layout continues unchanged from the original Super Sport, which is good since it didn’t need any change. The gas cap door on our bike was incredibly sticky to operate, resisting almost every effort to disturb it. However, since it’s the worst in recent memory we can’t believe they’re all like this.

There’s no headlight switch, of course— when the ignition goes on so does the headlamp, whether you like it or not. However, this isn't the problem it was on our 1975 test bike, which kept running its battery flat because the alternator couldn’t keep pace with the steady discharge of the lights. On the current Super Sport the battery will charge when the engine is run faster than 3200 rpm. Our test bike was a good proof of this arrangement, since it arrived with a rather sluggish battery and left with a full charge.

Cosmetically, the Super Sport speaks for itself. Even though the appearance doesn’t really go with the name—there are much sportier-looking rigs coming off other assembly lines on both sides of the world— the 550 looks terrific. The jazzy burnt orange metallic paint of the original Super Sport has been replaced by a handsome maroon with rich-looking gold striping. The chrome fenders continue with a rather traditional look—there hasn’t been any change toward a racier cafe treatment— and the Super Sport has yet to inherit Honda’s ComStar wheels. The overall impression isn't quite as traditional as something like Yamaha’s XS650, but it falls well short of the flamboyance of the Kawasaki KZ650 or even the previously noted Suzuki entry. If you’re looking for something that’ll inflame the senses of every boy racer on the block, try some other make. But if your idea of pleasant motorcycling doesn’t include the prospect of inciting your fellow cyclists to riot at every stoplight, this refined-looking rig may be just the thing.

Perhaps that’s the key to understanding this inaptly-named machine. If you disregard the words Super Sport, the Honda CB550F-77 is a consistent, handsomely packaged middleweight that will get you where you’re going in style and comfort. It’s no factory road racer—the current 550K, which differs from the Super Sport principally by having twin exhausts rather than the jazzier 4-into-l setup, is every bit as fast if not faster—but there’s enough muscle to provide that pleasant rush when you turn up the wick. It doesn’t take Kenny Roberts to get the suspension to its limits on winding roads, but not everybody needs to be Kenny Roberts. And there’s the bonus of Honda’s widespread sales/service organization included in the purchase price.

It’s an attractive package. Not superjust excellent. |ß

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOn Messing About With Motorcycles

October 1977 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsService

October 1977 By Len Vucci -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1977 -

Competition

CompetitionSears Point Revival

October 1977 By Tony Swan -

Competition

CompetitionSame Old Loudon But Better

October 1977 By John Waaser