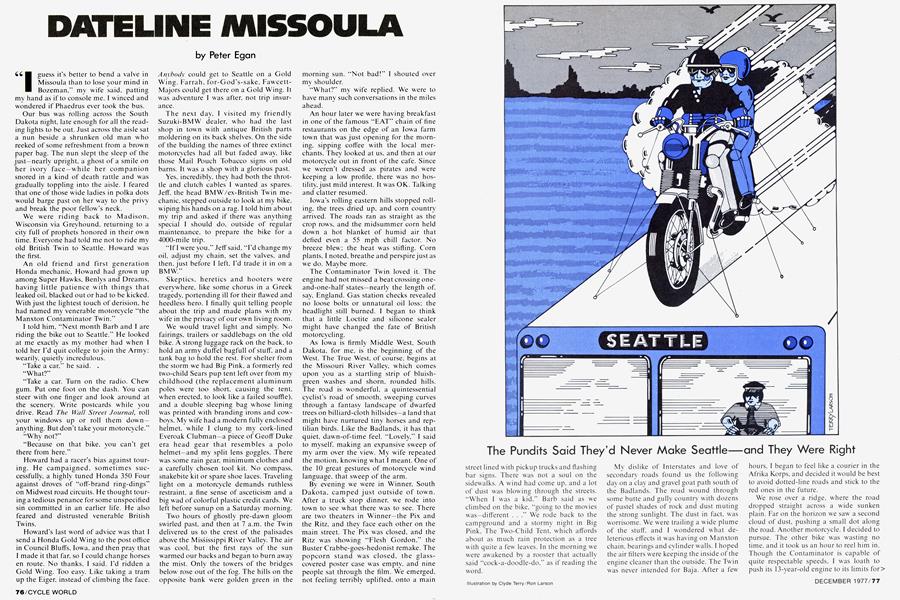

DATELINE MISSOULA

Peter Egan

I guess it’s better to bend a valve in Missoula than to lose your mind in Bozeman.” my wife said, patting my hand as if to console me. I winced and wondered if Phaedrus ever took the bus.

Our bus was rolling across the South Dakota night, late enough for all the reading lights to be out. Just across the aisle sat a nun beside a shrunken old man who reeked of some refreshment from a brown paper bag. The nun slept the sleep of the just—nearly upright, a ghost of a smile on her ivory face—while her companion snored in a kind of death rattle and was gradually toppling into the aisle. I feared that one of those wide ladies in polka dots would barge past on her way to the privy and break the poor fellow’s neck.

We were riding back to Madison. Wisconsin via Greyhound, returning to a city full of prophets honored in their ow n time. Everyone had told me not to ride my old British Twin to Seattle. Eloward was the first.

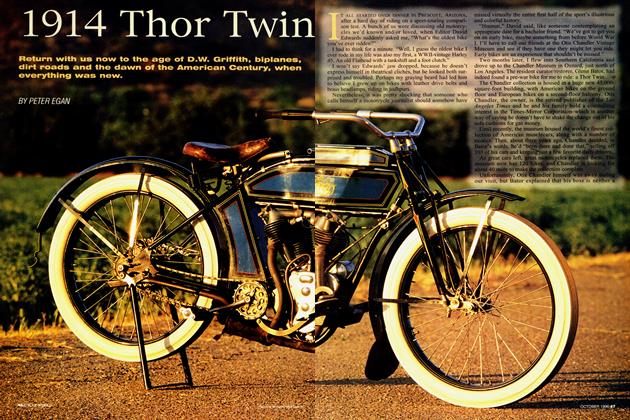

An old friend and first generation Honda mechanic, Howard had grown up among Super Hawks, Benlys and Dreams, having little patience with things that leaked oil, blacked out or had to be kicked. With just the lightest touch of derision, he had named my venerable motorcycle “the Manxton Contaminator Twin.”

I told him. “Next month Barb and I are riding the bike out to Seattle.” He looked at me exactly as my mother had when I told her Ed quit college to join the Army: wearily, quietly incredulous.

“Take a car,” he said. .

“What?”

“Take a car. Turn on the radio. Chew gum. Put one foot on the dash. You can steer with one finger and look around at the scenery. Write postcards while you drive. Read The Wall Street Journal roll your windows up or roll them down— anything. But don’t take your motorcycle.”

“Why not?”

“Because on that bike, you can't get there from here.”

Howard had a racer’s bias against touring. He campaigned, sometimes successfully, a highly tuned Honda 350 Four against droves of “off-brand ring-dings” on Midwest road circuits. He thought touring a tedious penance for some unspecified sin committed in an earlier life. He also feared and distrusted venerable British Twins.

Howard’s last word of advice was that I send a Honda Gold Wing to the post office in Council Bluffs. Iowa, and then pray that I made it that far. so I could change horses en route. No thanks. I said. I'd ridden a Gold Wing. Too easy. Like taking a tram up the Eiger, instead of climbing the face. Anybody could get to Seattle on a Gold Wing. Farrah. for-God's-sake. FawcettMajors could get there on a Gold Wing. It was adventure I was after, not trip insurance.

The next day. I visited my friendly Suzuki-BMW dealer, who had the last shop in town with antique British parts moldering on its back shelves. On the side of the building the names of three extinct motorcycles had all but faded away, like those Mail Pouch Tobacco signs on old barns. It was a shop with a glorious past.

Yes. incredibly, they had both the throttle and clutch cables I wanted as spares. Jeff, the head BMW/ex-British Twin mechanic. stepped outside to look at my bike, wiping his hands on a rag. I told him about my trip and asked if there was anything special I should do, outside of regular maintenance, to prepare the bike for a 4000-mile trip.

“If I were you,” Jeff said, “I'd change my oil. adjust my chain, set the valves, and then, just before I left. I'd trade it in on a BMW.”

Skeptics, heretics and hooters were everywhere, like some chorus in a Greek tragedy, portending ill for their flawed and heedless hero. I finally quit telling people about the trip and made plans with my w ife in the privacy of our own living room.

We would travel light and simply. No fairings, trailers or saddlebags on the old bike. A strong luggage rack on the back, to hold an army duffel bagfull of stuff, and a tank bag to hold the rest. For shelter from the storm we had Big Pink, a formerly red two-child Sears pup tent left over from my childhood (the replacement aluminum poles were too short, causing the tent, when erected, to look like a failed souffle), and a double sleeping bag whose lining was printed with branding irons and cowboys. My wife had a modern fully enclosed helmet, while I clung to my cork-lined Everoak Clubman—a piece of Geoff Duke era head gear that resembles a polo helmet—and my split lens goggles. There was some rain gear, minimum clothes and a carefully chosen tool kit. No compass, snakebite kit or spare shoe laces. Traveling light on a motorcycle demands ruthless restraint, a fine sense of asceticism and a big wad of colorful plastic credit cards. We left before sunup on a Saturday morning.

Two hours of ghostly pre-daw n gloom swarled past, and then at 7 a.m. the Twin delivered us to the crest of the palisades above the Mississippi River Valley. The air was cool, but the first rays of the sun warmed our backs and began to burn away the mist. Only the towers of the bridges below' rose out of the fog. The hills on the opposite bank were golden green in the morning sun. “Not bad!” I shouted over my shoulder.

“What?” my wife replied. We were to have many such conversations in the miles ahead.

An hour later we were having breakfast in one of the famous “EAT” chain of fine restaurants on the edge of an Iowa farm town that was just opening for the morning, sipping coffee with the local merchants. They looked at us, and then at our motorcycle out in front of the cafe. Since we weren’t dressed as pirates and were keeping a low' profile, there was no hostility, just mild interest. It was OK. Talking and clatter resumed.

Iowa’s rolling eastern hills stopped rolling, the trees dried up, and corn country arrived. The roads ran as straight as the crop rows, and the midsummer corn held dowm a hot blanket of humid air that defied even a 55 mph chill factor. No breeze blew; the heat was stifling. Corn plants, I noted, breathe and perspire just as we do. Maybe more.

The Contaminator Twin loved it. The engine had not missed a beat crossing oneand-one-half states—nearly the length of. say, England. Gas station checks revealed no loose bolts or unnatural oil loss; the headlight still burned. I began to think that a little Loctite and silicone sealer might have changed the fate of British motorcycling.

As Iowa is firmly Middle West, South Dakota, for me, is the beginning of the West. The True West, of course, begins at the Missouri River Valley, which comes upon you as a startling strip of bluishgreen washes and shorn, rounded hills. The road is wonderful, a quintessential cyclist's road of smooth, sweeping curves through a fantasy landscape of dwarfed trees on billiard-cloth hillsides—a land that might have nurtured tiny horses and reptilian birds. Like the Badlands, it has that quiet, dawn-of-time feel. “Lovely,” I said to myself, making an expansive sweep of my arm over the view'. My wife repeated the motion, knowing w hat I meant. One of the 10 great gestures of motorcycle w ind language, that sweep of the arm.

By evening we were in Winner, South Dakota, camped just outside of town. After a truck stop dinner, we rode into town to see what there was to see. There are two theaters in Winner—the Pix and the Ritz, and they face each other on the main street. The Pix was closed, and the Ritz was showing “Flesh Gordon,” the Buster Crabbe-goes-hedonist remake. The popcorn stand was closed, the glasscovered poster case w'as empty, and nine people sat through the film. We emerged, not feeling terribly uplifted, onto a main street lined w ith pickup trucks and flashing bar signs. There was not a soul on the sidewalks. A wind had come up. and a lot of dust w'as blowing through the streets. “When I was a kid,” Barb said as we climbed on the bike, “going to the movies was—different . . .” We rode back to the campground and a stormy night in Big Pink, The Two-Child Tent, which affords about as much rain protection as a tree with quite a few leaves. In the morning we were awakened by a rooster that actually said “cock-a-doodle-do.” as if reading the w'ord.

The Pundits Said They'd Never Make Seattle-and They Were Right

My dislike of Interstates and love of secondary roads found us the following day on a clay and gravel goat path south of the Badlands. The road wound through some butte and gully country with dozens of pastel shades of rock and dust muting the strong sunlight. The dust in fact, was worrisome. We were trailing a wide plume of the stuff, and I wondered what deleterious effects it w'as having on Manxton chain, bearings and cylinder walls. I hoped the air filters were keeping the inside of the engine cleaner than the outside. The Tw;in was never intended for Baja. After a few' hours, I began to feel like a courier in the Afrika Korps, and decided it w'ould be best to avoid dotted-line roads and stick to the red ones in the future.

We rose over a ridge, w'here the road dropped straight across a wide sunken plain. Far on the horizon we saw a second cloud of dust, pushing a small dot along the road. Another motorcycle. I decided to pursue. The other bike was wasting no time, and it took us an hour to reel him in. Though the Contaminator is capable of quite respectable speeds, I was loath to push its 13-year-old engine to its limits for> any distance, being no stranger to the Last Straw Theory of engine failure.

The other motorcycle stopped with us at a highway intersection. The bike was a Honda 550 carrying Tom. a friendly, slightly overheated-looking 18-year-old who happened to be from our home state. He looked at the Contaminator Twin with amazement. His 550 was clean and dry, while our Twin was covered with a thick layer of chalky dust that clung to all the oil that had sweated through the bike’s mated surfaces. It looked like the ghost motorcycle of the Plains. “You guys are a long way from home with that thing,” he said. I didn’t much care for the awe in his voice. It made me nervous.

We rode and camped with Tom for the next two days. He had left Wisconsin with $65, two weeks of vacation and absolutely no plans except to go “out West.” It was nice to ride with another bike, and the two machines made an interesting pair. The 550 whirred along silken and revvy, while the Twin sort of pulsed, and at a much lower note. The Twin had gearing left over from the age of 70 mph freeways, and turned less than 4000 rpm at that speed (in theory, of course), producing all kinds of torque right down to the 2000 rpm shudder barrier. Critics of British Twins have complained much about their vibration, yet that problem has never bothered me. since the vibration is more of a throbbing phenomenon than the sort of hectic, buzzing condition that drives feet off footpegs and hands from handlebars. With tall gearing, it is a one-pulse-every-telephone-pole vibration that merely assures the rider he is on a motorcycle and that his engine is still running.

On what was to be, it turned out, the last night of our cycle trip, we were turned back from Yellowstone Park by a “Yellowstone Full” sign on the entrance gate (now that folks can drive their houses out West, camping is more popular than ever), so we back-tracked to a very pleasant campground in the Shoshone National Forest. Just before sundown, a group of chopper aficionados with mamas rode into camp, set up tents, then raced off to nearby Pahaska Teepee Lodge Bar. They returned at closing time, cycles blazing. After riding around their own tents until a couple of their bikes tipped over, they settled down to about 15 minutes of shouting “Ya-hoo!” and “Krrriii!” and punching each other in the shoulder, before building a five billion BTU log and tree-stump fire. Someone got out a guitar and they all sang “Dead Skunk in the Middle of the Road” until passing out at 3 a.m.

“That’s pretty good,” Barb said at one point during the party, “listen to them sing. They .all know the words. When was the last time you heard 20 people who all knew the words to the same song, singing together like that?” “Church?” I suggested. “Or maybe the Army . . .”

She listened for a while, then shook her head. “No, that’s not the same.”

The Twin started hard (i.e.. not at all) in the morning. The weather was cool, and the 50-weight oil about as viscous as three quarts of Smuckers topping. Each time I jumped on the kick starter, the engine went “tufff” and moved through half a stroke. Our friend Tom turned on his gas, set the choke, hit the starter button, and then walked away to brush his teeth while the Honda quietly purred and warmed itself up. Something was not right with the Contaminator. Usually two kicks, no matter how slow, were enough to make it fire. That morning, we finally pushed it down hill while I popped the clutch. It started reluctantly and ran less smoothly.

“Bad gas,” I said. “It's that dishwater they're selling as premium now.” Tom said goodbye and turned south toward the Tetons. while we pushed north into Montana. If ever a license plate blurb carried a grain of truth, it is Montana’s “Big Sky Country.” There is no other place in the world where you are eternally surrounded by mountains that are forever 50 miles away. We rode up the Madison River Valley into the first rainstorm of the trip, invincible in our rubber rain suits. By noon, a cool wind dried the pavement and we were on the dreaded Interstate—our only choice—near Butte, headed for a night with some friends in Moscow, Idaho. After 1400 miles and five days on the road, the Manxton Contaminator Twin still lived, running better than it had any right to. I began to suspect that we would not only reach Seattle, but possibly even make it home again. I felt guilty, however, pushing this old sporting machine over endless miles of Interstate, even for one afternoon. It was like some interminable torture test, with the engine hovering at one constant, dull, unvarying pitch. Finally, the Twin decided it had endured enough.

Someone at a Yamaha shop said one guy in town might be able to fix the Manxton if he had the parts, which he didn’t, but he was on vacation.

About 25 miles from Missoula, the engine gave out a raucous mechanical clatter and stopped running on one cylinder. We pulled over, removed the rocker covers, and found three hundred thousandths of rocker clearance on the right-hand exhaust valve. It was not returning all the way. Bent, as it were. The right cylinder had just enough compression to blow one very faint smoke ring. I adjusted the tappet to cut down some of the clatter and tried to restart the bike. Oddly enough, it started and ran. We were on our way, albeit not too swiftly or silently. For 25 miles, the (now) Contaminator Single pulled us across the country, up and down hill, at 45 mph.

I listened to the engine for sounds of further disaster, waiting for the worst. The bike kept on. lugging its 300-lb. burden of passengers and gear on one tired cylinder. My emotions vacillated wildly; I couldn’t decide whether to heap abuse or praise on the machine. But it was a painful ride for us like forcing a crippled horse to run. We were exhausted from tension by the time we reached the fjrst motel Missoula had.

Some quick telephone calls confirmed the worst. No shop in town had parts for, or could fix. the old Manxton. No one knew where to get parts, or anyone who even had such a bike. Someone at a Yamaha shop said one guy in town might be able to fix it if he had the parts, which he didn’t, but he was on vacation.

The next morning, on Missoula’s Annual Hottest Day of the Year, we pushed the Twin two miles across town to a Bekins freight office. The proud Manxton, which had conquered the Bighorns with impunity, now had me trembling at the sight of Missoula's manhole covers. As we pushed, swarms of children on bananaseat bicycles encircled us and asked clever questions or made witty remarks. Why, I asked myself, aren’t these children working in coal mines or textile mills, where they belong? By the time we finished pushing I'd made a mental note to refrain from having any children, and had, at the same time, found new respect for the latent energy in a cup of gasoline. We filled out all the forms and mailed the bike home.

The trip to Moscow, Idaho, and then to Seattle was made by bus and train. We took the Greyhound home.

Riding in the bus, I thought about the trip and about the motorcycle. When the Twin arrived home, I would fix the valve, clean the engine, polish the chrome, and keep the bike for special occasions like Sunday rides, the way one uses an MG TC or a Piper Cub. It deserves care, rest and respect, as do all things that carry their age with grace. I had, unfairly, asked too much of the motorcycle. My fault.

Everyone had warned me what might, or surely would, happen. My own instincts had warned me. I knew the trip to be an undertaking whose outcome was uncertain. There was plenty of good advice to that effect. On any of a dozen other motorcycles our finishing the trip would have been a foregone conclusion. Maybe, in the end, that was why we took a 13-year-old British Twin. It’s not so terrible, just two weeks out of the year, to not know what’s going to happen next.

As the South Dakota night slipped by. I looked out the bus window and fell to aimless reverie. Could a Honda 50,1 found myself wondering, make it all the way from Madison to Mexico City ...