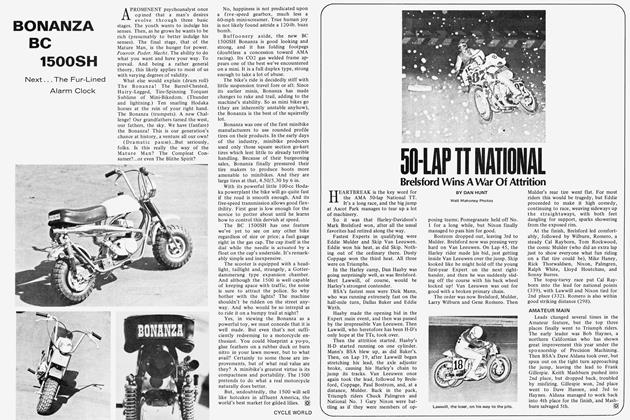

ROAD RIDING

DAN HUNT

RAIN RIDING

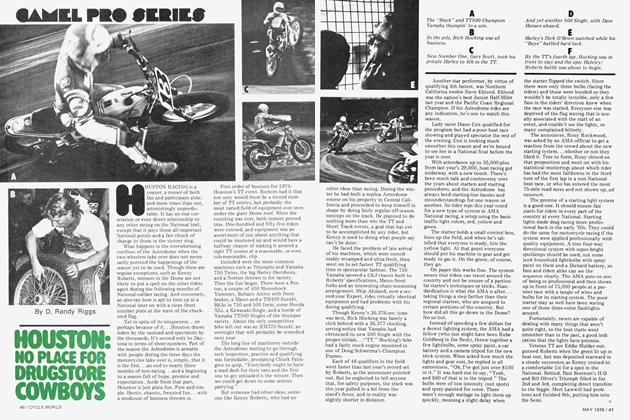

Another surpriser in wet weather is the puddle that is only a few inches deep. If you hit one of these at 50 mph upwards, the water splash thrown back from the front tire is enough to unseat you and/or blast your feet from the pegs. Water that is three or four inches deep gives an absolutely fantastic effect in that regard. I attacked just such a water-crossing at 55 mph on the Isle of Man and was hit back so hard that it kicked both my legs straight back, totally obscured my vision and

wrenched my left hand from the handlebar. Never again.

Riding when it is actually raining is not impossible but takes some pre-planning. Whether you wear goggles or use a face plate, you’ll find that your vision is being obscured. Light rain causes spots to appear on your goggles, and the spray from traffic makes an annoying coating of dirt spots. Heavy rain can be more desirable, as the spots give way to a relatively clear sheet of water.

If you ride in rainy country, consider getting riding gloves with a little piece of chamois attached to the back. A quick pass of the back of the hand over the goggles every few minutes will smooth new droplets into passably transparent water film.

Lens fogging will be your next problem. As moisture works it way to the inside of the goggle or the face plate, it may condense if the lens is cold and thus fog the inside. Face plates are particularly bad because you breathe warm air on them. Your only choice is to stop and clean the things. If you can’t get the insides perfectly dry, the fogging will start all over again just as soon as you put them back over your eyes. Defogging solution, a liquid coating available at some bike stores, may prevent the problem, but who in the hell ever remembers to bring the stuff along?

Ultimately, your best bet is to reduce your speed to 35 or 40, and leave the goggles off. You may be able to go faster without tearing your eyeballs out if you can crouch low enough to duck below the windstream. Some bikes are remarkably friendly in this regard. The Honda 500 Four, for instance, had its instruments canted up in such a way as to create a high pocket of still air over the handlebars. If you crouched so that your head was 12 inches above the gas tank, you could ride at 100 mph in complete comfort with no goggles.

NIGHT RIDING

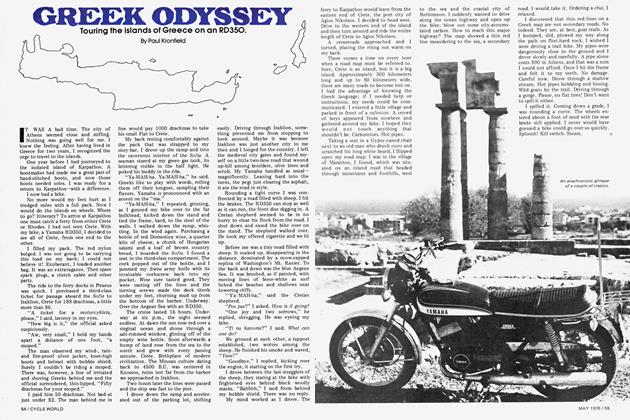

Night riding has always been somewhat of a neat thing for me. It’s almost sexy. You alone, or you and your woman slipping through the dark. Night marauders, adventure, the Unknown, smuggling, missions of mercy, malevolence and mystery all blend together in a stimulating psychological stew and enhance an otherwise run-of-the-mill sort of pastime.

You won’t be doing much hot and heavy riding at night. Vision is greatly impaired. Many of the cues that a motorcyclist takes for granted during the daytime are gone. In poorly lit areas, the black envelope surrounding your single headlight can produce vertigo in a steep bank. The road surface is hard to , read, and you may even ignore large objects that have fallen on the road. Oil slicks get slicker as moisture condenses on the cooling pavement. The same thing goes for painted lines. So you don’t press so hard, and you’re doubly careful about scanning the pavement for hazards.

Riding at night begins in the daytime. Wear sunglasses out of doors during the day because it will benefit night vision. Starting out at night, take it easy for 20 minutes if you have come from lighted indoor surroundings, so that your eyes may acclimate themselves to the darkness. And, naturally, you should make sure that your lighting equipment is in proper shape. Such a suggestion borders on the obvious—all except for the fact that few motorcyclists ride at night. And fewer run periodic checks on their headlights, taillights, high and low beam and dimmer switch. One common emergency caused by non-checking is when the rider switches from low to high beam and discovers that the high beam is burnt out. Further, you should know the characteristic operation of your dimmer switch: does it require a rapid flick of the switch because slow switching will produce a blank spot in the middle where both high and low beams are extinguished momentarily? Nothing puckers the old sphincter like thundering through the darkness with the headlight out. Another common foul-up: adjusting the headlight beam with the bike unloaded may produce an errant beam when you are aboard. A single beam doesn’t offer the effectiveness of the automotive double beam. A badly aimed single beam is almost useless.

In traffic, you’ll find yourself less aggressive than you are in the daytime. That’s fine. At night, it’s handy to use traffic as a shield, the car in front of you pre-lighting the road for you and allowing you to better examine possible road hazards coming your way. Behind is the greatest concern: does the driver know you’re there? And if he knows, is he sober enough to care? You can usually gauge his attitude by the distance he keeps. If the following driver’s distance is consistently the same at all times, the guy is on the ball. If it varies from comfortable to dangerously close, chances are you have an accident waiting to happen. Ditch him at the earliest opportunity, even if it means pulling off the road to let him pass.

In town, the greatest hazards are generated by the lack of good contrast and the bright oncoming lights. The two combine to make it hard to identify side street traffic, or pedestrians stepping out between parked cars. Out in the country, the job is relatively easier, because you can spot oncoming cars miles away from the halos and reflections created by their lights. But those lights may dazzle you as they get close. You can avoid being blinded by looking slightly away from the lights as they get close enough to be intense.

One thing to consider when night riding is your own capabilities of vision. Your vision may be quite adequate in the daytime. But night lighting may reveal some inadequacies, notably the tendency of light images to fragment and glare. Try squinting at distant lights sometime; if the images become markedly more resolved, you should think about getting glasses fitted before hitting the road at night. Keep in mind that both cigarettes and booze greatly inhibit night vision. And the booze will contribute to vertigo.

If you prepare for the night and ride it conservatively, it can be a pleasant and moving experience.

SNOW RIDING

It may sound crazy, but thousands of Europeans road ride in the snow, even going so far as to have an annual winter rally and camp-out high in the Alpines.

When you ride in the snow, you leave many of the classier skills of riding behind. You may look like rigor mortis on two wheels, but if you are still up on two wheels, you are just as good as the next guy. Keeping warm is the second most urgent problem after keeping up.

First, riding in the snow requires

premeditation. You need appropriate tires. Balls-out cafe racing tires won’t make it unless you’re traversing only a few small patches. A block-pattern trials universal tire, or at least a small pad universal tread is necessary both front and rear. You’ll find that the trials tire won’t be as obnoxious for smooth pavement riding as you might have suspected, and offers little vibration at ~ speeds up to 70 mph. The flat trials profile puts nearly all of the blocks on the ground where they belong. Since your cornering technique in snow consists of slowing in a straight line, turning at a snail’s pace with as little bank as possible, and accelerating gently in a straight line, the trials tire profile couldn’t be more appropriate.

In the snow you should plan all stops far ahead of time, accomplishing the majority of the slowdown on engine compression. Rear braking is very touchy and in extreme doses will lock the back wheel. If the engine stops and locks, you’re faced with riding a fully developed brake slide to its conclusion. If you have to slide at all, however, a rear wheel slide is better than a front wheel slide. To prevent the latter, use the front brake only when the bike is straight up and steady, and not at all when there is ice on the road.

Acceleration in the snow is accomplished the same way porcupines make love. Carefully. Throttle-induced backwheel spin in the snow is not a neck-snapper by any means, and instead occurs as a sweeping whoosh. Its gentleness, however, is overshadowed by the ease with which the rear wheel moves sideways. It if happens to you, gradually back off on the throttle, and try to keep the bike straight up, without trying to force or steer the wheels back into alignment. The bike will straighten its path more or less automatically when the spinning stops.

Different types of snow differ in the power with which they make you pucker. The easiest stuff to ride is semi-soft, semi-powder layer about one or two inches thick. The tires sink in just a little, enough to prevent the wheels from slipping sideways, unless, of course, you’re banking at dangerous extremes. Occasionally, I clean the blocks of my rear tire by briefly spinning the back wheel in this stuff.

Freshly sanded snow, or that which has been scraped and sanded, also provides a relatively minor challenge.

When the weather in your area has been changing rapidly following a snowstorm, you should worry. Take the situation where snow falls, followed by a warming trend. So far so good. Some of the snow is melting, and much of your travel will be over cleared patches of snow and water run-off. Then a new cold front moves into the area overnight and the water freezes into a smooth, hard-to-see coating. Ice.

(Continued on page 38)

Continued from page 37

Most of you don’t have to be reminded how hairy it is to ride on ice, even with trials tires. But if the new front brings more heavy snow, which in turn is scraped and salted, you may have a traction problem that is hidden under the fresh stuff. Fresh snow on ice is deceiving and treacherous. If you take a spill on the ice, you can console yourself with the thought that even the best riders don’t have a chance on ice—unless they have spiked tires.

General advice for snow and ice: keep plenty of space between you and traffic, in front or behind. If you go down, try to lay the bike down sideways, cross-steering the bars and pulling your leg back from underneath the machine. This type of controlled crash may be your only choice with stopped traffic ahead. If your front wheel started to slide when you tried to stop, let go of the front brake and convert to a back-wheel slide. When the bike is down and stopped, don’t sit there stunned. Run, crawl, jump or scramble off the side of the road, or at least start moving that way until you’ve seen that the cars following you have come to a full stop.

Steep downhills are the worst thing you’ll have to deal with in snow riding. On a downhill, everything is going against you: gravity, traction, weight transfer and the stop sign just ahead. If you must, think about the consistency of the snow and what traction it will offer while you are still on the crest of the hill, or just before. Ride downhill in proper sloth-like manner, and if things get worse than you could have ever guessed, good luck. If there’s a comfy snow bank at the side of the road, use it. Head straight into it. If it isn’t that kind of snow bank, get on the back brake and lay her down sidewaysplanning the finish with both hands on the bars, one foot on top of the brake peg and the other foot out from underneath the bike. If you don’t like the possibilities I’ve outlined in the preceding tips and hints, stay home by the fire.

WEATHER FORECASTING

Either night or day, sometimes the best thing to do is avoid bad weather entirely. This is often easier said than done, due to the vagueness of the forecasts given by the various media. The wary motorcyclist, however, may improve the quality of the weather picture he gets by some careful reading and a local phone call.

(Continued on page 115)

Continued from page 38

The careful reading involves finding a newspaper that has enough class to run a national weather map. These maps picture weather fronts and often show where the fronts are traveling along with an approximate regional indication of what kind of temperature and precipitation the front is going to bring.

Use this map to give yourself a long-range big picture of weather trends in your proposed region of travel. Don’t use it as gospel, as the map is undoubtedly several hours old when it’s printed in the newspaper.

Then, to make your picture more precise, you have two alternatives. One is to procure one of those little VHF radios that receive the National Weather Service broadcasts on 162.55 Mhz. National Weather Radio formats its round-the-clock broadcasts into regional forecasts of what’s going to happen in the next 12 to 24-hour period, local weather summaries of what weather conditions exist at key towns and landmarks within a roughly 200-mile radius during the last few hours, and extended weather forecasts that will help you plan a trip with a rundown of what will probably happen in the coming three to five days. You will find that listening to the forecast and interpreting it in the light of present weather reported at a point 100 miles away or so will give you accuracy you never dreamed of.

If you don’t have access to a VHF portable, you can telephone usually locally one or more governmental services that give the weather. Look in the telephone book under UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT, then find TRANSPORTATION, DEPT. OF. Under that last category you’ll see the item, Transcribed Aviation Weather Broadcast. It’s a long-winded tape recording that gives you a brief regional forecast, and then rattles off what’s happening in airport towns near and far, some as far as 800 miles away. In the Los Angeles area, for instance, the “TWEB,” as they call it in flyer’s jargon, gives 12-to-l8-hour forecasts and observed conditions along the routes from San Diego through Los Angeles to San Francisco, from Los Angeles to Banning to Blythe, and from Los Angeles to Daggett to Las Vegas. The detail will drive you crazy, but it’s free (paid for with taxes) and peppered with quaint aviation oddities like “icing layer at one-zero-thousand (10,000) feet” or “aircraft operation is not permitted in area P-25 within a four-mile radius from zero to 4000 feet (Nixon’s San Clemente pad, where he goes to rest between China trips).” When you hear the term SIGMET applied to an area forecast on TWEB, listen carefully because it usually means drastic weather, like violent winds, thunderstorms, ice, hail, and downpour. If you hear the term AIRMET, it is usually associated with milder bad weather such as light rain, fog, or moderately gusty winds.

Don’t mistake the TWEB telephone number for the Flight Service Station or the Pilot Briefs and Flight Plans numbers. You may be charming enough to convince the personnel answering that you’re a neat guy and should be indulged in your request for a forecast, but more than likely you’ll be stopped dead when the guy asks for your aircraft registration number and you can’t give him a decent sounding facsimile. Unless you’re a licensed pilot, leave these latter two number to the pilots who need them. The Transcribed Weather Broadcast will be more useful to you anyway.

The best weather forecast is an accurate account of the big picture, and a fairly recent rundown of what is happening NOW in the area you’ll be reaching in the next few hours. Either TWEB or Weather Radio can give you this information. With remarkably little effort, you can find out at any time whether the best policy is to press on, or lay low over hot coffee at a road side diner for a few hours.

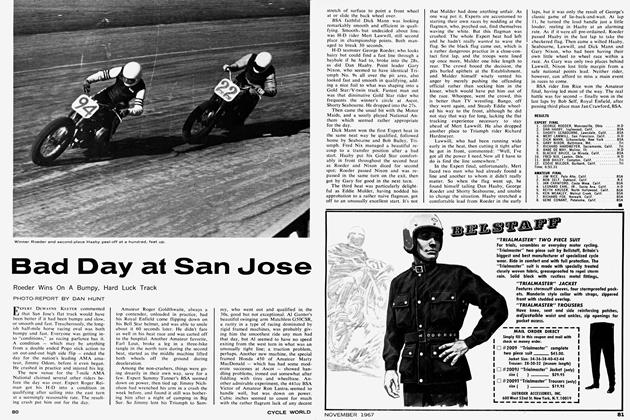

GOING THE DISTANCE

Distance riding requires a different frame of mind than that you have for an aggressive Sunday afternoon of fun. It is more deliberate, demands more planning if it is to be a comfortable affair, and requires sustained periods of selfdiscipline and self-awareness.

The enemies of the distance rider are fatigue, soreness, sustained periods of adverse weather, complacency about the mechanical state of the motorcycle, and sometimes apathetic and semi-delirious states of mind. I met a rider in France who had been on the road for seven days straight, having started in Greece. He had pulled his cylinder head all by his lonesome at the side of the road, just a few miles from town, suspecting a serious malfunction. He paid dearly to have the machine put back together. Ah yes, the diagnosis: he had run out of gas! Quite obviously his head wasn’t screwed on straight. Had the trouble been in the cylinder head, really and truly, he wouldn’t have been able to fix it at the roadside once he had removed it anyway!

To me, going the distance means planning ahead enough so that I minimize fatigue, and loading and equipping my bike so that it carries enough to satisfy my needs without being so overloaded that it ruins my taste for hard riding.

If you’re the intrepid and constant long-distance traveler, you’ll, invest in a windscreen, full fairing or handlebar fairing. I avoided them during my tours of Europe, but paid for my stubborn ways on several occasions during rain and extreme cold. Once upon a time I capitulated and bought a plastic screen to keep the bugs off on my way from Los Angeles to San Francisco. I hated it, and noticed that my Superhawk ran at only 75 mph instead of 85 mph. But, I must admit that I was a lot less tired when I arrived, and a lot less beaten. Recent handlebar fairings are more efficient against the air than was that simple flat-screened model; fairings like the Wixom and Vetter models produce little or no penalty in drag, although they still have some sensitivity to side gusts.

If you are one of those guys who thinks a motorcycle is a truck, and who likes to pack 75 pounds of gear, okay. But please remember that extreme loading will affect the handling of your machine.

Before you stack everything you ever owned on the back of your machine, either directly on the seat, in saddlebags, or up the full length of a threefoot sissy bar, remember that the leverage of those bags on the rear can really jerk you around. Whenever you can, split the load into a few bags, carrying the most dense and heaviest loads forward if at all possible, preferably on the gas tank. If you load everything to the rear, the first time you put the bike into a turn too hot, you’ll find that your rearward load is undulating you right off into the bushes. And once you get undulating the effect of poor weight distribution is like an uncontrollable beast you may find those frightening oscillations have made loose what you thought was a fairly good tie-down arrangement.

The best advice is to narrow down what you take along to what you really need. . .and then narrow it down some more. Nothing can turn a vacation into a hassle faster than dragging around too much baggage, particularly if it never gets used. I’ve found that if you’re riding solo you rarely need more than what can be contained in a normal flight bag, the kind that measures about 18 inches long. Take some of the lug out of luggage and give you and your bike a break.