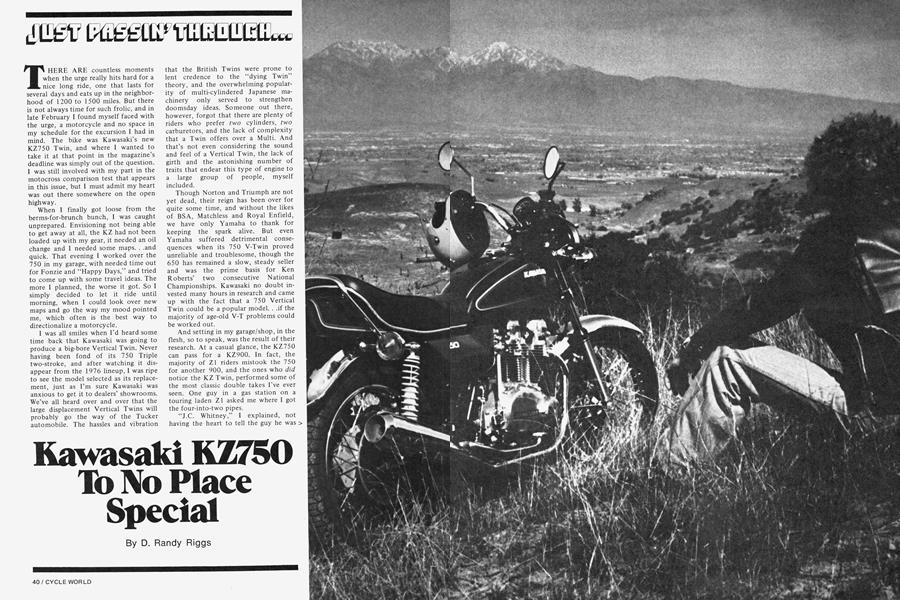

Kawasaki KZ750 To No Place Special

JUST PASSIN' THROUGH...

D.Randy Riggs

THERE ARE countless moments when the urge really hits hard for a nice long ride, one that lasts for several days and eats up in the neighborhood of 1200 to 1500 miles. But there is not always time for such frolic, and in late February I found myself faced with the urge, a motorcycle and no space in my schedule for the excursion I had in mind. The bike was Kawasaki’s new KZ750 Twin, and where I wanted to take it at that point in the magazine’s deadline was simply out of the question.

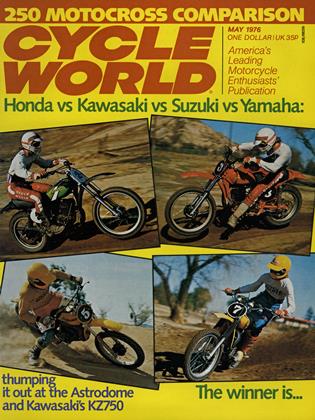

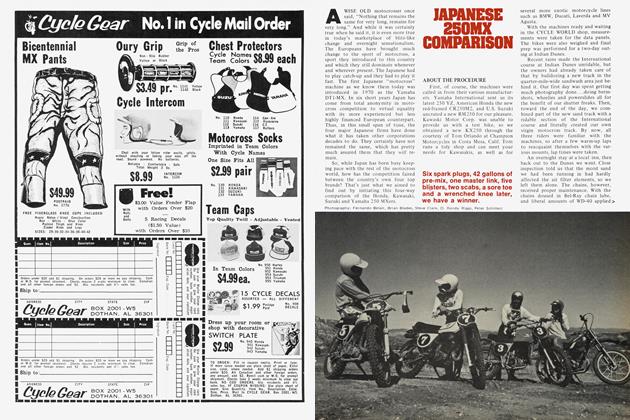

I was still involved with my part in the motocross comparison test that appears in this issue, but I must admit my heart was out there somewhere on the open highway.

When I finally got loose from the berms-for-brunch bunch, I was caught unprepared. Envisioning not being able to get away at all, the KZ had not been loaded up with my gear, it needed an oil change and I needed some maps. . .and quick. That evening I worked over the 750 in my garage, with needed time out for Fonzie and “Happy Days,” and tried to come up with some travel ideas. The more I planned, the worse it got. So I simply decided to let it ride until morning, when I could look over new maps and go the way my mood pointed me, which often is the best way to directionalize a motorcycle.

I was all smiles when I’d heard some time back that Kawasaki was going to produce a big-bore Vertical Twin. Never having been fond of its 750 Triple two-stroke, and after watching it disappear from the 1976 lineup, I was ripe to see the model selected as its replacement, just as I’m sure Kawasaki was anxious to get it to dealers’ showrooms. We’ve all heard over and over that the large displacement Vertical Twins will probably go the way of the Tucker automobile. The hassles and vibration

that the British Twins were prone to lent credence to the “dying Twin” theory, and the overwhelming popularity of multi-cylindered Japanese machinery only served to strengthen doomsday ideas. Someone out there, however, forgot that there are plenty of riders who prefer two cylinders, two carburetors, and the lack of complexity that a Twin offers over a Multi. And that’s not even considering the sound and feel of a Vertical Twin, the lack of girth and the astonishing number of traits that endear this type of engine to a large group of people, myself included.

Though Norton and Triumph are not yet dead, their reign has been over for quite some time, and without the likes of BSA, Matchless and Royal Enfield, we have only Yamaha to thank for keeping the spark alive. But even Yamaha suffered detrimental consequences when its 750 V-Twin proved unreliable and troublesome, though the 650 has remained a slow, steady seller and was the prime basis for Ken Roberts’ two consecutive National Championships. Kawasaki no doubt invested many hours in research and came up with the fact that a 750 Vertical Twin could be a popular model. . .if the majority of age-old V-T problems could be worked out.

And setting in my garage/shop, in the flesh, so to speak, was the result of their research. At a casual glance, the KZ750 can pass for a KZ900. In fact, the majority of Z1 riders mistook the 750 for another 900, and the ones who did notice the KZ Twin, performed some of the most classic double takes I’ve ever seen. One guy in a gas station on a touring laden Z1 asked me where I got the four-into-two pipes.

“J.C. Whitney,” I explained, not having the heart to tell the guy he was all wet in front of his girlfriend, who was looking on adoringly. “They sure look nice,” he said. “Yup,” ‘ I said back, “almost like factory jobs.” Sometimes I just can’t resist when someone leaves himself wide open like that.

CON

Kawasaki was smart when it designed the 750 to resemble the 900. But as similar as the two machines look, very few parts are interchangeable. Tank, seat, tail section, passenger assist bar, front and rear fenders, side covers, even the headlight “ears” are different. A few bits and pieces are identical, but only a very few. The important thing, though, that Kawasaki kept foremost in its mind, was concept.

The big K already has the performance and large-bore Multi market well handled with the 900 Four; and the KZ400 Twin has done a remarkable job for the commuter riders. There are three two-stroke Triples for those so inclined, but the gap that needed filling was the vacated 750 slot. And there are no doubt plenty of people who are wondering why Kawasaki didn’t fill the position with a Multi of some size, shape or form. Honda has sold more than 100,000 of its 750s, and Yamaha is about to unleash a Triple in the same displacement category. And many remember that Kawasaki produces a 750cc Four called the Z2 for the Japanese market. Why didn’t they simply start bringing it into the U.S.?

That’s easy enough to answer. We can go back to what I mentioned earlier about the largely untapped group of Twin lovers that is still out there in force and waiting for something like the KZ750 to come along.

In the several hundred miles that I’d already racked up on the machine in daily commuting, the thing that impressed me most about the new engine was the remarkable amount of torque it produces. This has much to do with Kawasaki designing the unit with a 360-degree crankshaft, in which the pistons move up and down at the same time, the cylinders taking alternate turns at firing every other revolution. Vibration, of course, is a point that’s always brought up whenever Vertical Twins are discussed, and to combat the inherent nature of this undesirable trait, the KZ uses counterweights, one fore and one aft of the crank. The weights on the KZ are chain-driven off the four-main-bearing crank assembly, and produce harmonics of the same intensity but opposite those being produced by the crank and pistons. This nullifies much of the shake, rattle and roll that would be present without the balancers.

It’s kind of interesting to note that the KZ750 bottom end is very similiar to that of the KZ400; and the top end, with the dual overhead cams and all, looks like the KZ900’s. The cams, like those in the 900, are chain-driven off the crank, and the lobes run directly on the valve stems. Valve adjustment is accomplished by adding washer shims in cups on the tops of the valve stems. Since valve adjustment is seldom required on the Z1 models, I’d expect the new 750 to follow suit. There is yet another chain, this one is a Morse Hy-Vo type, for the primary drive, necessary because of long, lower engine cases. The balancers need room down there to spin, and the result is a lengthy bottom end.

Because of the chain primary drive, the crank must turn “backwards” (clockwise toward the rear of the machine) so the primary sprocket will spin in the right direction. This is a bit unusual, but goes unnoticed by the rider.

As with the Zl, the oil level on the 750 may be checked through a window on the clutch cover housing. The oil filter is a.cartridge-type element identical to the one found in the KZ900. To get to the unit for servicing, one must remove the shift lever, the primary sprocket cover and the left footpeg, which is only somewhat bothersome. The engine will take just over four quarts of oil after a filter and oil change.

A crankcase breather nestles on top of the transmission cases. Inside are baffles that trap oil droplets before they get into the atmosphere; fumes are passed back through the air cleaner and reburned.

Ignition is via a single set of breaker points and an AC generator keeps things in the 12-volt/14-amp-hour battery charged.

The bore/stroke is square 78mm x 78mm-for an actual displacement of 745cc. Carburetors are Mikunis of the constant velocity type and are 38mm in size. To drown any intake roar or noise, a huge airbox assembly carries a paper element that fits in a canister that has a twist-off lid. If the filter is dirty, it gets thrown away, not cleaned.

As I worked over the 750 it was apparent that it was a much easier machine to maintain than a Four would be for the average owner; also less expensive to service if taken to a dealer. The initial cost is about $500 cheaper than the 900, and a few hundred cheaper than the most popular bike in this displacement class. That should set well with many potential riders.

The following morning the KZ was loaded with my gear and we headed for the Auto Club of Southern California for some maps. . .and hopefully for some route ideas. I’ve always found membership in the Club to be quite beneficial. They’ve provided me with friendly service and always seem more interested in the trip when I tell them it will be done on a motorcycle.

I still wasn’t sure which direction to go, though in the time allotted there wasn’t much choice outside of Southern California, unless a blitz was made up the state and back, which isn’t my idea of a relaxed trip. That’s one thing I enjoy about traveling in the Northeast; you can ride through many states in a day and it seems as though lots of ground is being covered. In a place like Texas, it doesn’t seem as though you’re moving along at all!

I pointed the Twin north toward Laguna Beach and mingled with the early morning traffic, most of which was heading for Newport Beach, where our offices are located. There’s a small, quaint coffee shop/restaurant in Laguna that is worth a stop at breakfast time; it was breakfast time, so the KZ and I did the inevitable.

There was a perfect spot in front of the place to park the bike where it could be watched while I thought my way through the first meal of the day. Just to give it a try, I stuck the key in the steering head lock and twisted. The bars have to be almost full turn to the left before the lock will work, and it takes some fumbling. The helmet holder/lock is mounted up on the handlebars, and it dawned on me as I struggled to get the “D” ring of my Bell Star over the lock tab that something was really dumb about this arrangement. Anyone with the proper size alien wrench can unbolt the lock from the bars, and the helmet goes with it. So I left it be and carried the helmet in with me.

Nursing coffee, 1 stared some more at the motorcycle through the window and thought about the impressions it had left on me up until that point. It had been a very enjoyable machine so far; it s willingness to handle a variety of traffic situations was impressive. The KZ weighs in excess of 500 pounds with fuel in the tank, and yet, at no time had it ever felt like a 500-lb. motorcycle. Much of the weight must be concentrated on a low plane because, based on feel alone, I would’ve guessed that the 750 Twin weighed 50 to 70 pounds less than a KZ900, when, in actuality, the difference is just under 20 pounds.

The brakes had been squeaking, particularly the rear unit, a new disc arrangement. I wondered if the noise would go away or get worse. The latter seemed to be happening.

Much of the bike appeared to be put together reasonably well. The paint and decaled striping were smooth and the chrome looked decent. All the pieces seemed matched to one another; noth ing appeared to be out of place or ungainly. I think the KZ750 will find many who appreciate its styling, even if they can’t tell it from its bigger brother, the 900 Four.

After breakfast I unlocked the machine, swung a leg over and rolled off the centerstand. It’s no problem for me to rest my feet flat on the ground when sitting on the bike, but I’m six feet tall. Someone shorter than 5 ft. 10 in. will find the KZ on the tall side and will be tip-toeing at the stoplights. An easily reached tab welded on the arm permits the rider to flip out the sidestand from a sitting position. The ignition switch is right up between the instruments and there are individual warning lights for oil pressure, neutral and high beam, and directional arrows for the turn signals. There is an operational headlight switch, a feature the KZ400 should pick up on.

The only gripe I had with the switches was the horn button, which really isn’t a button, but more like a spring-loaded rocker switch. Several times I found myself needing the horn (which is another joke) and pushing away at the wrong side of the button, which is easy to do with a gloved hand. What is needed is a normal type button hooked up to something that makes some noise. . .or has that wonderful government mess, the EPA, cracked down on horns that go “Beep?!”

Starting was always very quick with the 750. The choke is usually needed if the engine is cooled down at all, but only for a quick instant, after which it can be slackened off as the engine picks up temperature.

The sound is unmistakably Vertical Twin, yet with an individual personality thrown in. Throttle response is instantaneous and crisp, revs build and unwind quickly. The KZ is very quiet, down in the required 83db range, so there is no need to fear disturbing good ol’ John Q. If you liked the way earlier Triumph and BSA Twins made sounds, you probably won’t be too thrilled with the nasal tone of the KZ pipes, but that’s life in the big city these days.

I took the San Diego and Ventura Freeways all the way to Ventura, the cut off on Highway 33, into the heart of the Los Padres National Forest. With some cruising miles on the bike, I noticed only a minor degree of vibration through the handlebars and footpegs. The bars have hard rubber grips, so with thin gloves or no gloves at all, the vibration could get unpleasant after a while. But with thicker gloves or more generously padded grips, no one should be unhappy with vibrations, unless they like cruising at 80 mph or greater. . .and that's pretty hard to get away with in this day and age of wall-to-wall cops.

(Continued on page 92)

KAWASAKI

KZ750

$1975

Continued from page 44

The torqueyness I mentioned earlier makes for passing on the highway with out the need to downshift. In fact, much of the time, even around town, I found myself in fourth or fifth gear, with the engine running merrily away beneath me. Cruising in higher gears also serves to negate one of the machine's bad traits, which is a large amount of drivetrain slack that is not uncommon among many Japanese motorcycles.

Gear ratios aren't spaced close to gether and with the engine as strong a puller as it is, they don't need to be. The transmission shifts satisfactorily and neutral proves to be no problem when it comes time to find it.

There are some nice, bendy portions of road along 33, and the 750 was a pleasure through them. Steering is light and easy, even at higher speeds. An average rider will have to work at dragging appendages. The left is easier to ground because of the centerstand hanging out, but the right-side footpeg will only be touched in really hard going. As long as the road remains on the smooth side, the KZ will track well and hold a groove. . .or even change lines without difficulty. But throw in some roughness, and the lack of sophis ticated suspension can give the rider heart failure if he's going places in a hurry.

I think it's kind ot sad that so much progress has been made in dirt bike suspensions in the last few years, while the manufacturers just keep right on bolting junky components onto their street machinery. There are exceptions, of course; the BMW and RD400 Yamaha are two examples. But, by and large, street machinery is in a bad state of affairs suspension-wise, and I think street bike buyers are getting cheated.

When I got to Uorman in the lejon Pass, I picked up Highway 138, a straight stretch through the high desert, and stopped in Lancaster for lunch. Lancaster is in the heart of the Antelope Valley, an area that's really grown in the last 1 5 years. Every time I come through I hardly recognize the place, what with fast food joints, car lots and dirt bike accessory stores. Someday it'll probably look like the San Fernando Valley, which is overpopulated and a mess of plastic signs mixed with cement and asphalt. To think that it was once only farms and orange groves.

Through Little Rock I got on an other section of 138 bound for Lake Arrowhead, a resort area in the San Bernardino Mountains. The snow capped peaks were visible in the clearness of the beautiful day, and I wondered what it would be like up on the mountain.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 92

The KZ would go on reserve almost like clockwork every 170 miles, and it was averaging 53 mpg. I had gotten a high of 58 during a prolonged steady cruise, and a low of 46 during a particularly hard run in traffic and through the mountains. I really was enjoying the motorcycle; the seat hadn’t gotten to me, nothing annoyed excessively. I would have preferred lower bars, because the stock units really stick a rider up in the wind. The mirrors vibrated enough to where I’d roll off the throttle and clutch the bike to check on Smokey Bear; the suspension bumped too much on the bumps; and the drive train slack required careful throttlehand coordination to eliminate jerkiness.

I know there will be those who will want a faster machine. The KZ will not open the eyeballs of those who enjoy seeing scenery rush by in a blur. But the thing is just so damn enjoyable to simply ride, that, as an all-around machine, I’d take it over a KZ900 any day of the week.

Although it had been warm during the morning along the coast and in the desert, the air began cooling noticeably as I headed back into the mountains. At Silverwood Lake I stopped and put on my Full-Bore riding suit, which had been strapped to the seat behind me. The brakes were still squealing and squeaking as I slowed for bends in the road, but all else was in order. Kawasaki has fitted Bridgestone tires to the 750 and they seem to have characteristics that are sticky enough without a high wear factor. It was easy to heel the bike over to its cornering limits without fear of the tires breaking away. I wish I could say that about all the test machines I ride.

When I got to Arrowhead I rode around and explored a bit, overjoyed with the total change in climate. Here it was full-on winter; snow was on the ground and the temperature was in the high thirties. But the cold made me sorry that I had ground away the side portion of the toe on my Sidi boots the previous weekend at an AFM road race. There was enough of a hole in the left boot to allow quite a numbing draft on my foot, so I had to stop and do some taping. The seat unlocks on the KZ and flips up, the tail section has a handy storage compartment. Inside . I had stashed a small roll of duct tape, a can of chain lube and a foam tire inflater bottle. Near the back of the seat base is a document holder, where the owner’s manual can be stored. The toolkit is ample enough to perform duties such as chain tightening and the like. I’ve been surprised to find tool kits in the past that didn’t even include a wrench to loosen an axle nut.

(Continued on page 95)

Continued from page 94

To take some of the chill off, I made yet another trip into an eatery and filled my stomach for the ride home. Outside once again, the weather had moved in, and snow was in the air. The bank sign said it was 33 degrees, it was really clouded in, and rain was falling lightly. While topping off the 3.8-gal. tank in a gas station, I asked the attendant about the weather and what it might be like going down the mountain.

“If you think the fog is bad here, wait till you get out on that rim,” he said with a grin, obviously enjoying what he thought was a predicament.

“Oh, I don’t care about the fog. . .it’s ice that I’m worried about.”

“Well,” he said, “if you head down the mountain now I wouldn’t worry about it. . .but don’t stick around too long. . .once it gets dark it’ll turn icy for sure.”

He was right about the fog on the rim. . .I’ve never experienced much worse visibility. It was like being on instruments in an airplane. I had to keep wiping my shield inside and out because the dew point must have been unreal. . .everything was fogging over. . . the mirrors, even the paint on the tank.

I pulled over in a turnout and wiped my shield clear with a cloth. Visibility was only about 10 feet in spots. After suiting up once again, a short line of traffic headed past in my direction and I tucked in behind them. Several miles down the twisty road, we broke out of the fog and into light rain. The KZ was still purring along and the tires had impressed me in the wetness.

Near Riverside the rain stopped and the sun began peeking through the clouds. I glanced back at the mountains, their tops invisible in the clouds. The temperature was back into the high ‘60s, but up there it was probably starting to snow.

Home again at nightfall, I covered close to 400 miles in the day-long trip, having been to the beach, the desert, the mountains, and sampling both spring and winter weather. Southern California offers a lot, and so does Kawasaki’s new KZ750 Twin. I guess one really doesn’t need a week to clear the cobwebs. . .a good motorcycle and a day will do the job just fine.