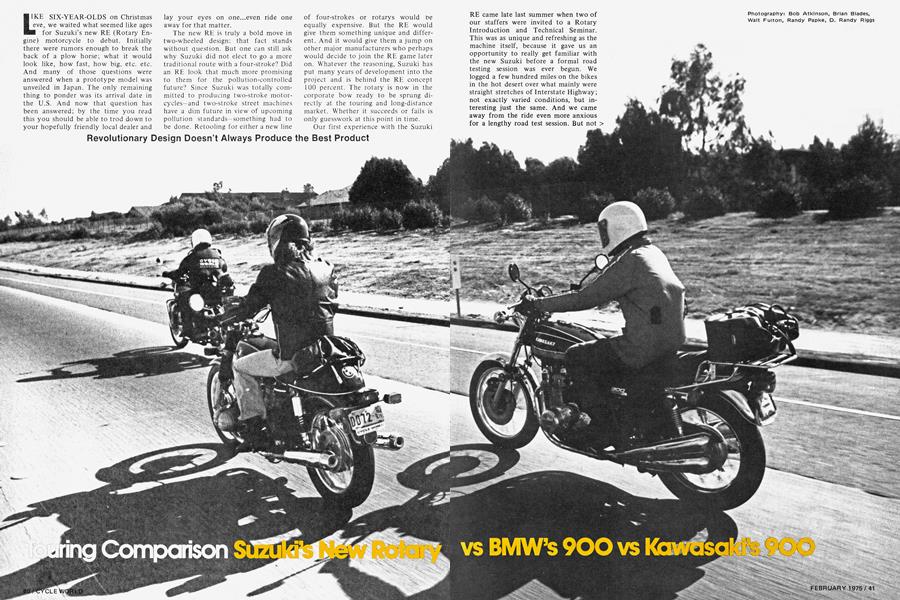

Touring Comparison Suzuki's New Rotary vs BMW's 900 vs Kawasaki's 900

LIKE SIX-YEAR-OLDS on Christmas eve, we waited what seemed like ages for Suzuki’s new RE (Rotary Engine) motorcycle to debut. Initially there were rumors enough to break the back of a plow horse; what it would look like, how fast, how big, etc. etc. And many of those questions were answered when a prototype model was unveiled in Japan. The only remaining thing to ponder was its arrival date in the U.S. And now that question has been answered; by the time you read this you should be able to trod down to your hopefully friendly local dealer and lay your eyes on one...even ride one away for that matter.

The new RE is truly a bold move in two-wheeled design; that fact stands without question. But one can still ask why Suzuki did not elect to go a more traditional route with a four-stroke? Did an RE look that much more promising to them for the pollution-controlled future? Since Suzuki was totally committed to producing two-stroke motorcycles—and two-stroke street machines have a dim future in view of upcoming pollution standards—something had to be done. Retooling for either a new line of four-strokes or rotarys would be equally expensive. But the RE would give them something unique and different. And it would give them a jump on other major manufacturers who perhaps would decide to join the RE game later on. Whatever the reasoning, Suzuki has put many years of development into the project and is behind the RE concept 100 percent. The rotary is now in the corporate bow ready to be sprung directly at the touring and long-distance market. Whether it succeeds or fails is only guesswork at this point in time.

Our first experience with the Suzuki RE came late last summer when two of our staffers were invited to a Rotary Introduction and Technical Seminar. This was as unique and refreshing as the machine itself, because it gave us an opportunity to really get familiar with the new Suzuki before a formal road testing session was ever begun. We logged a few hundred miles on the bikes in the hot desert over what mainly were straight stretches of Interstate Highway; not exactly varied conditions, but in teresting just the same. And we came away from the ride even more anxious for a lengthy road test session. But not > just any road test.

Revolutionary Design Doesn’t Always Produce the Best Product

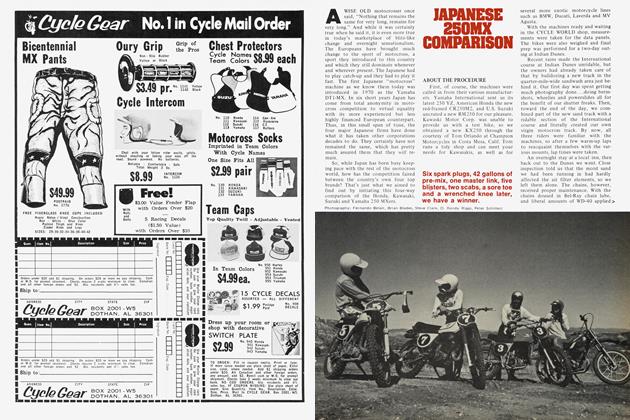

RE5 vs R90/6 vs Z1B

Since Suzuki was placing so much empasis on long distance, since they were touting smoothness, reliability, and the good things that should go hand in hand with a touring cruiser, we stacked it up against two of its competitors in all kinds of weather, on all kinds of roads, for plenty of miles.

We selected two particular machines to compare against the RE; Kawasaki’s famed 900.Z1 from Japan, and Europe’s long-distance king, a BMW R90/6. Both are established touring machines with other attributes, as well; all three are marketed for the person with the need or love for a large motorcycle. When all three are ridden together on long excursions and in everyday use, the results can get quite interesting.

Each motorcycle was picked up from its U.S. West Coast distributor; the rotary came from U.S. Suzuki in Santa Fe Springs, California; Butler & Smith supplied us with the R90/6; and Kawasaki Motor Corp. loaned us the Z1. Both the BMW and Kawasaki were in their break-in periods, showing about 300 and 600 miles on their odometers, respectively. The RE Suzuki was one of the first six that had been brought into the U.S. and was among the bikes used in Suzuki’s RE introduction to the press. It was well broken in, with close to 2500 miles on the odometer.

Each machine was freshly tuned, but nothing special was done to any of the bikes. No optional equipment was added, with the exception of a Triple A luggage rack to the Z1 on the trip portion of the test. We just needed some extra space and happened to have the rack in our shop; it was removed later on.

CATEGORY ONE SUGGESTED RETAIL PRICE BMW . $3220. 1 Kawasaki $2475 3 Suzuki $2475 3

Before we go any further, let’s clarify our reasoning for comparing the RE Suzuki to the other bikes in the test. A lot of readers out there are going to wonder about fairness, since technically one might consider that the RE’s 497cc is up against the likes of two 900s. This is where one must begin to assess Suzuki’s marketing concepts for the RE, which are, like we mentioned earlier, geared directly for the big-bike market. Both it’s bulk and price put it up there with the top guns. And current rotary theory indicates that to get equivalent piston engine displacement with the RE, the RE displacement must be multiplied by two; in this case the new Suzuki would come out as a 994. Makes thing pretty even, doesn’t it?

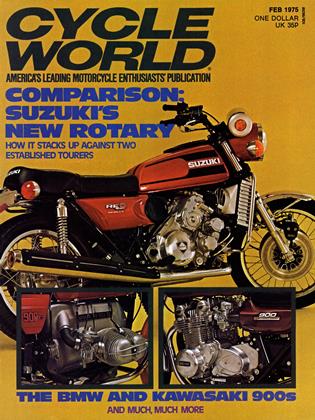

SUZUKI RE5

Anyone at all remotely interested in motorcycles seemed to recognize the new Rotary Suzuki immediately. It was roughly akin to streaking; not a soul missed your passing. But it’s not at all surprising. The RE5 really looks different. It’s interesting that an Italian had a hand in the styling, because a few similarities to the Benelli Six show up here.

Although beauty is in the eyes of the beholder, none of us on the staff were that thrilled with the RE’s styling. Suzuki seems to have a good basic start down there under all that gimcrack, but the festoons only serve to make a strange conglomeration out of the entire motorcycle. A direct front view greets the observer with a gargantuan radiator assembly that has been overemphasized with a silver-gray plastic grille unit and chrome crash bars.

If you ask, “So how in the heck do you hide a radiator?”, look at the new Honda 1000 to find out.

The turn indicator lights look as though they were pirated from the roof of an ambulance, yet are less effective brightness-wise than the much smaller units fitted to the BMW. The headlight sealed-beam unit is barely average in brightness, but the nacelle and instrument pod are designed with only styling (?) in mind. There is no provision for up and down adjustment on the beam, just a small amount of side to side action. And you could live with that maybe if the unit were aimed upwards enough to begin with, but that’s not the case. At night we always rode around with the high beam on; even it is so far off target that vehicles traveling in front don’t notice.

Then there’s that instrument cluster. Did that ever get the comments on our test runs. “Looks like a mini-sleeping bag.” “That thing a jewelry box?” “Wow, a Panasonic radio on your handlebars!” But really, what is its purpose, besides being a styling ruse? Suzuki says the hinged, tinted green plastic cover prevents the faces of the instruments from fading after prolonged exposure to the sun. We all know how motorcyclists have for years been suffering severe instrument fade. . .and at last there’s a cure!

The cover flips open at the twist of the ignition key to expose the speedometer, water temp gauge, tachometer and six warning lights to view. The speedo reads, unnecessarily, to 160 mph, meaning the needle will hover in the first third of its arc the majority of the time. There’s an odometer with a reset feature, handy on a machine that’ll go only slightly farther than 150 miles on a full tank of fuel. And the tach needle revolves in a steady manner, easy to read at a glance.

Warning lights abound. From left to right they go like so: fuel tank level, oil tank level, oil pressure. . .all glow red. From there comes the neutral light in green, turn indicator in amber and high beam in blue. And if that’s not enough, a digital read-out in red lets the rider know what gear he or she is in. As a double check, they could bend down and glance at the engine casting near the shift lever, where the shift pattern is cast in for easy reading.

The temperature gauge can come in very handy, since the RE has a tendency > to run on the hot side of things. In heavy traffic or hard running in hot weather, overheating is a possibility, despite the large radiator and cooling fan.

During our initiation run in the desert we had experienced some cooling problems with a few of the rotarys. Suzuki’s mechanics diagnosed the problem as foreign material in the fuel, which plugged the fuel filters, creating a lean condition and the eventual heat problems. But in our recent road testing evaluation, our test machine again got extremely warm on a medium hot day; the cooling fan had to work overtime to keep things on the happy side of trouble. Some coolant was lost out through the overflow tube, which dumps directly in front of the rear tire! That certainly could prove interesting at the wrong moment!

Handlebars are too backswept and straight up and down for our preferences, but they’d work just fine with a fairing. Incidentally, coinciding with the RE introduction, Suzuki will offer a full fairing as an option for the RE at all its dealerships. Grips are too hard, but not as poor as some. The control switches, however, are all. excellent, both in placement and operation.

CATEGORY FOUR CARRYING CAPACITY (GROSS VEHICLE WEIGHT, MINUS MACHINE WEIGHT W/HALF-TANK FUEL) BMW..... . 421 lb..... .....3 Kawasaki . . . 348 ....... .....2 Suzuki .... . 339 ....... .....1

Available within reach of the left thumb is the horn button,' a turn indicator switch that operates in a leftoff-right manner for no confusion, and also lighting controls. The right side is fairly basic, with an emergency rockertype cutoff switch and the starter button.

Colors available on the RE Suzuki are Firemist Blue and Firemist Orange. The blue is the more conservative and features silver accent bands; the orange color is highlighted with black panels. Paint is applied to the tank and side panels only. Most of the rest of the machine is chrome or polished metal.

Visual inspections of fluid levels may be carried out easily enough, if you care not to believe in warning lights. The tank under the seat contains 3.6 pts. of Shell Super X 10-20-50 oil for the automatic lubrication system. This oil lubes the rotor seals and makes a miserable attempt at getting to the drive chain. We really like the idea of a warning light here, because it lets the rider know when he can add one full quart of oil to the tank. Crankcase oil can be checked quickly with a plastic dipstick located on the right side of the engine. Suzuki recommends the same oil for both crankcase and metering tank.

(Continued on page 50)

Continued from page 46

Locks are abundant. The forks lock, the seat locks (but you can’t leave it unlocked), a locking lid covers the radiator and fuel tank caps and there’s a helmet lock. The lid is cheap and spoils an otherwise unobtrusive looking tank; it even mars the finish on the tank, since there are no pads to keep it from coming into contact with the unit.

There is no question about Suzuki RE styling being on the complicated side. It’s as busy a motorcycle as you’ll ever lay eyes on. Quality is on par with average Japanese equipment, but you’ll find that when it comes time to polish and clean, it’ll be an all-day job. So many spots are impossible to reach, like the inside of that plastic cover for the instruments, for just one example.

Cleaning the Rotary is a nightmare. Period. And it’s far from the cleanestoperating motorcycle we’ve ever ridden. But more on that later.

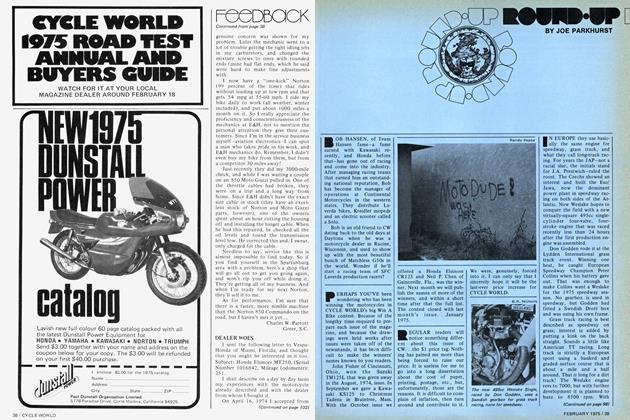

KAWASAKI Z1B

Few machines over the years have commanded the attention and respect that the Z1 has earned in just a very short while. Even in its introductory year, the bike had few flaws. Little needed changing. The present-day Z1B follows suit. With a couple of minor incidentals, the big Kaw is much like the original.

The paint scheme has been diddled with. Suspension has been changed slightly to allow a smoother ride. But it’s all very subtle. We miss the black engine though. All that black with the polished fins and protuberances really added a special touch of class to an already classy motorcycle.

One thing, however. The first Zls> were known chain-eaters. So Kawasaki had a deal to replace the first chain under the liberal warranty program. Now they may have a better answer. The new chain is a special selflubricating type; with some care, Kawasaki expects life to average 10,000 miles. Though we didn’t ride ours that far, we can report that after 2500 miles our chain had not been adjusted, nor had it been lubed. And it still looked perfect, without the presence of an oil-soaked rear wheel and tire. The only hitch is that they’ll be expensive when the time does come to replace them.

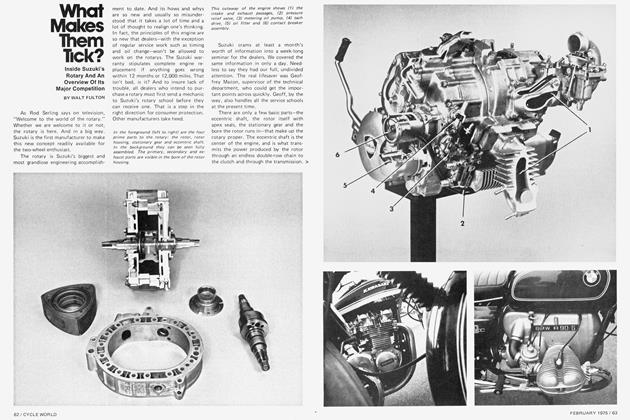

BMW R90/6

$3195

BMW R90/6

The 900cc version of BMW’s flatTwin was added with the introduction of the 1974 models. A road test of that machine appeared in the February ’74 CW. A test of the R90 Sport version followed in August. Last month we tour-tested a 1975 model R75/6, which has the same improvements as the 900 in this issue. This is without a doubt the most conservative looking machine in the group, leaving the gasp grabbing oohs and ahs up to its sportier brother. . .or is it sister?

Some find the jutting cylinders peculiar; to others they may be the indication of the finest motorcycling has to offer. Whatever, the latest BeeEm has new handlebar switches, a perforated front brake disc, new levers, different seat padding; and the kickstarter has been removed and placed on the option list.

BMWs are known throughout the world as the finest in long-distance machines. We rather doubted that the latest version would smear any of that reputation.

After the machines were weighed on our certified scales, and the various measurements taken, the staff began a familiarization period with each of the motorcycles. This involved the usual commutes to work, and pleasure rides of up to 200 miles in length. Such use was intended mainly to check out each bike for any troubles or bugs. Every gas fill-up was measured, all mileage and pertinent data was recorded and monitored. A trip was planned from our Newport Beach office; and after a final check of equipment, we headed north.

The schedule called for a rider change on the machines daily, so that each of us—Bob Atkinson, Walt Fulton > and D. Randy Riggs—had equal time on every bike. The only real plan in the trip was to cover as large a variety of roads and conditions as we could in the time allotted. . .a fairly easy task in the state of California.

The first leg was started after dark. Atkinson took the RE Suzuki, since he had only recently completed the introductory ride in the desert and had been riding to work on the machine. Fulton bolted the luggage rack from his own Z1 to the test Kawasaki and was anxious to see if he could recognize those subtle changes he had read about in the manual. And Riggs, who had just completed a trip back East on a new 750 BMW and had only recently taken delivery on a new R90S, was the logical choice to ride the R90/6 the first night out.

The imagination stumbles over itself wondering what a rotary-engined motorcycle will feel like. And believe us when we tell you, the sensation is a whole new experience. The Suzuki starts effortlessly each and every time. By depressing the enrichment lever marked “choke” on the left side of the engine, the rider is but a short “click” from something new. The ignition switch is located just under the instrument “pod”; and turning the key one short twist to the right activates things. There is a high-pitched sound coming from the ignition that is only loud enough to be heard with good ears and no traffic noise close at hand.

The “pod” cover flips upward, warning lights glow, one almost wonders whether to push the button marked “starter.” Once depressed,the engine is running; there is no hesitation. But the sound is new, and much louder than expected. RE idle is peculiar; no comparisons can be drawn with the RE Mazda automobile, though many people try to do just that. The Suzuki emits an idle that’s a cross between those of a four-stroke and a two-stroke. The bada-bump, ba-da-bump sound disappears with rpm, whereupon it takes on the characteristics of an electric motor without a muffler, if you can imagine such a thing.

Immediately apparent to the rider is an inordinate amount of throttle slop, which we understand Suzuki is working to eliminate. But as it stands, it is one of the most glaring faults of the RE5. It’s one of those pesky things that is difficult to adjust to, no matter how long you ride with it.

Once the bike is off the stand and supported by the rider, hefting it from side to side gives a big, fast clue to the bulk of the motorcycle. Get it too far over center and you might as well get out of the way, because it’ll plop on over. The Z1 feels almost as big, but the BMW seems like a motocrosser after climbing off the others. Because the BeeEm has a much lower center of gravity and about 100 pounds less weight, that comes as no surprise.

Clutch pull on all the bikes is medium-light, and each makes with a resounding clunk when dropped into first gear. The Suzuki, however—due to the large flywheel inertia—never becomes a smooth shifter. BMW used to receive a fair amount of criticism for the same reason. But by going to smaller,> lighter flywheels and a five-speed box, they reduced the “clunk” considerably. Suzuki, though, has to stick with the large flywheel, and gearbox smoothness is probably as good as it will ever get. And the transmission wasn’t nearly as smooth and slick shifting as the gearboxes in the Kawasaki and BMW.

KAWASAKI Z1B

$2475

Where the Suzuki makes up for the clunk is in the level of engine vibration. Of course, this is what people proclaim to be the prime virtue of the rotary engine. It makes no difference to the RE whether it’s turning 1500 or 7000 rpm. Buttery smooth remains the constant. When the rider can see clearly in > the rear view mirrors at 100 mph, that’s revolutionary.

We’re not saying that the RE is totally vibration -free, because a peculiar sort of a shake develops when the engine is placed under load. This is caused by forces generated on the eccentric shaft that create a “rocking” effect upon it. The feeling transmitted to the rider is one of a chain slipping on a sprocket or something similiar to chain whip. The trait isn’t uncomfortable, but noticeable.

Cruising along at freeway speeds, the Suzuki has a sound all its own. Surprisingly enough, the engine runs quieter at higher speeds than at lower ones. When riding in the company of the BMW and Zl, in fact—particularly at traffic speeds near parked cars-the RE5’s noise level is on the objectionable side. We don’t care what the db meters read, the RE will furrow a brow or two.

A perfect example occurred at a motel in Santa Barbara. We had just loaded up the machines to prepare for an early morning departure. The three bikes were parked just outside a room where some custodial people at the motel were having coffee and reading the morning paper. We started the engines to let them warm up; first the BMW, then the Kawasaki. The people didn’t so much as give us a glance. But when the RE was fired up, not only did they look up from what they were doing, but one of them went over and shut the door!

On long, straight runs the BMW is easily the most comfortable of the three. The suspension has no peer for absorbing road shock and bumps, nor does it mind a heavy load. Thanks to the best seat in motorcycling and lowfrequency, large-amplitude engine vibration, one can ride the BMW for countless uninterrupted miles.

The Kawasaki is also blessed with a good seat, but its suspension isn’t up to the comfort-delivering capabilities of the BeeEm. Nor does it feature the rider/machine relationship of the German tourer. But it is still easier to live with for long periods than the RE Suzuki, whose biggest long-distance shortcoming is the seat and jouncy suspension.

Up Highway 1 things get very twisty, and we rode hard to push the bikes to their limit. We had expected the Suzuki to be short on ground clearance, but the opposite is true. There’s more than enough. When flogged, all three of the bikes will play tricks; ground clearance on the BMW and Kawasaki is limiting; the BMW suspension is too soft; the Suzuki has a high center of gravity that tends to pick the machine up in a corner. Yet each motorcycle offers the vast majority of riders more than they’ll ever be able to use in cornering ability. These are safe machines as they stand and, for those who desire it, they can be made better for spirited riding. But people interested in touring won’t be heeling the bikes over on their engine cases; they’re far more interested in things like fuel range and economy, ease and frequency of maintenance, carrying capacity, etc. When you sta rt considering all these factors, the field narrows considerably.

Well into the test, the BMW was beginning to amaze us. Not only was it delivering 50 mpg most of the time, but it was eating the Zl alive in throttle-rollon contests from different speeds. It > was supremely comfortable and cleanoperating. Meanwhile, the RE Suzuki was beginning to look as though it had been run in a stock car race. The fork seals were leaking profusely and blowing oil all over the radiator grille and front portion of the motorcycle. When parked, it left small puddles of oil, reminiscent of early-day British Twins, and that’s no joke. The chain oiler had successfully glopped oil all over the rear of the machine. . .but not the chain. It was dry and stretched and needed frequent adjustment. We began oiling the chain by hand since it was obvious that the automatic oiler was doing anything but.

SUZUKI RE5

$2475

The Kawasaki isn’t blessed with a driveshaft like the BMW, but it too, was doing an admirable job of staying clean, at least until the rains hit. This was an excellent time to check out fender protection, wet-pavement tire performance and areas that don’t normally give trouble until it gets damp. None of the bikes, however, gave a hint of trouble. And when it started snowing in South Lake Tahoe, we headed for warmer climate. None of the machines make good snowplows.

CATEGORY ELEVEN PENALTY POINTS BMW-4 Power turn indicator switch location Carburetor interference with rider’s right leg Driveshaft oil leak at engine junction Passenger and rider footpegs too close together KAWASAKI-5 Poor hand grips Instrument glare during daylight hours Excessive mirror vibration Broken turn indicator switch Slow-speed wobble caused by outof-true front tire SUZUKI—5 Too difficult to get bike up on centerstand Sloppy throttle Fork seals leak Poor drive chain life (chain wore out during test) Engine oil leaks

When we finally did return from the trip portion of our testing, we investigated wheel removals, routine servicing, quality of toolkits and owners manuals. . .items that can make ownership of a bike pain or pleasure. Again the BMW shines. For example, one can remove and replace both front and rear wheels on the BMW in less time than any one wheel on the other machines. And it can be done alone, without outside help. The centerstand is balanced perfectly to keep the bike standing with either wheel removed.

The owners manual is full of needed information. So the owner can follow the manual through a service and tuneup, performing it easily himself using the tools provided with the machine. And by now you know that BMWs are equipped with a tire pump, tire irons and a patch kit to fix those flats. Simplicity abounds, as does reliability and well-rounded performance. That adds up to satisfaction to the nth degree.

In the end, you come up with three remarkable motorcycles, each capable of performance that wasn’t even dreamt of only a few short years ago. But each is remarkable for a different reason. The BMW glows because of its utter simplicity and astounding quiet performance, coupled with economy and supreme comfort that many miles will prove out.

The Kawasaki Z1B glimmers in its own sunshine. No other machine can deliver such thunder and lightning or be as subtle as a quiet summer morning sunrise. It, too, has a reputation for reliability and operational economy, though not to the degree of the BMW. Let us not forget those four carburetors and cylinders and various complexities.

And then there is the new Rotary. Remarkable because it is here. . .because Suzuki made it work. . .for its smoothness and technical engineering. . .but little else. If the RE proves reliable and troublefree, Suzuki has a good beginning. It’s now time for them to round out the rest of the package.

The BMW was the unquestionable winner of our touring comparison. It won because it does well in all of the categories that touring machines should be judged in. It may not be tops in everything, but it never is very far off. But they’ve been building BMWs since the 1920s. That leaves plenty of time to stomp on the bugs. And, lest we forget that list price, it’s $3220. For that, it better be good.

Kawasaki was very close with its first Z 900. So close, in fact, that the present model shows few changes. Due to inflation, it’s not quite the buy that it once was, but it still delivers everything the original did. And for that reason it remains one of the best buys in motorcycling.

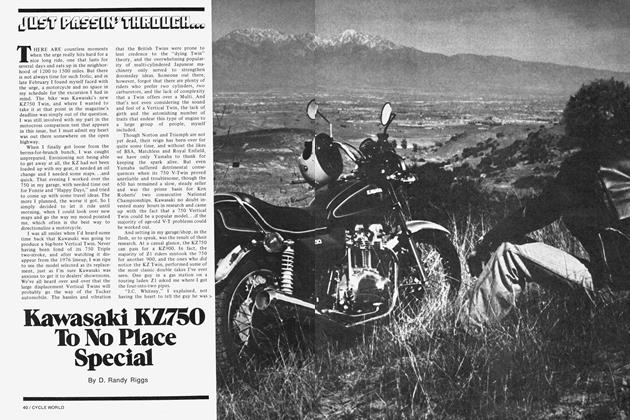

Maybe Suzuki put too much effort into the new engine and neglected the little necessities. Less concentration on styling foo-foos and more on the things that make a motorcycle right would have helped the RE’s point standing a great deal. Somehow, the Rotary just misses the target. Yet many will buy it for newness alone—because it’s unique and different.