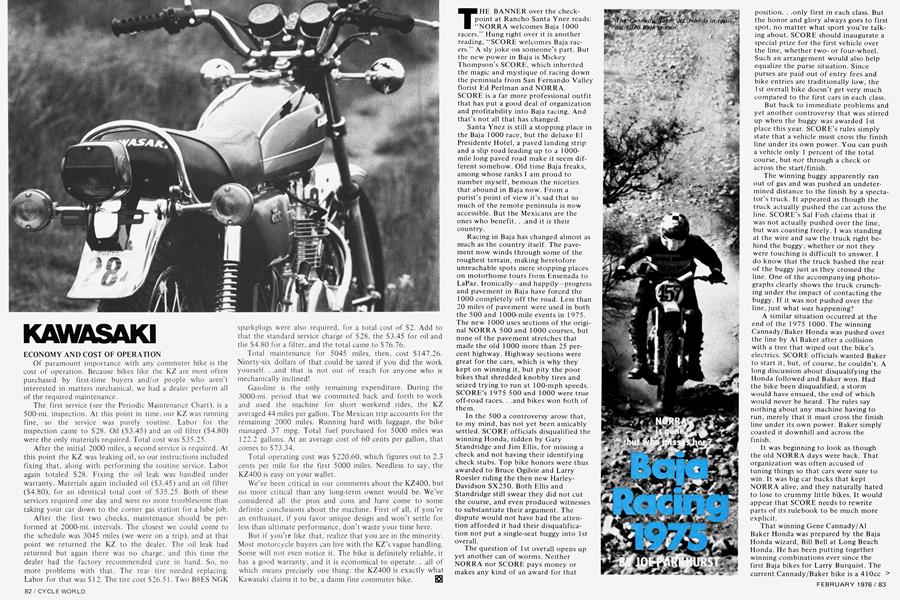

Baja Racing 1975

NORRA is gone but who misses her?

JOE PARKHURST

THE BANNER over the checkpoint at Rancho Santa Ynez reads: “NORRA welcomes Baja 1000 racers.” Hung right over it is another reading, “SCORE welcomes Baja racers.” A sly joke on someone’s part. But the new power in Baja is Mickey Thompson’s SCORE, which inherited the magic and mystique of racing down the peninsula from San Fernando Valley florist Ed Perlman and NORRA.

SCORE is a far more professional outfit that has put a good deal of organization and profitability into Baja racing. And that’s not all that has changed.

Santa Ynez is still a stopping place in the Baja 1000 race, but the deluxe El Presidente Hotel, a paved landing strip and a slip road leading up to a 1000mile long paved road make it seem different somehow. Old time Baja freaks, among whose ranks I am proud to number myself, bemoan the niceties that abound in Baja now. From a purist’s point of view it’s sad that so much of the remote peninsula is now accessible. But the Mexicans are the ones who benefit. . .and it is their country.

Racing in Baja has changed almost as much as the country itself. The pavement now winds through some of the roughest terrain, making heretofore unreachable spots mere stopping places on motorhome tours from Ensenada to LaPaz. Ironically—and happily —progress and pavement in Baja have forced the 1000 completely off the road. Less than 20 miles of pavement were used in both the 500 and 1000-mile events in 1975. The new 1000 uses sections of the original NORRA 500 and 1000 courses, but none of the pavement stretches that made the old 1000 more than 25 percent highway. Highway sections were great for the cars, which is why they kept on winning it, but pity the poor bikes that shredded knobby tires and seized trying to run at 100-mph speeds. SCORE’S 1975 500 and 1000 were true off-road races. . .and bikes won both of them.

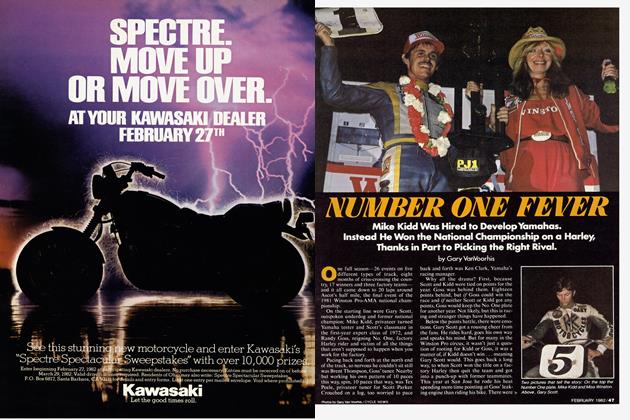

In the 500 a controversy arose that, to my mind, has not yet been amicably settled. SCORE officials disqualified the winning Honda, ridden by Gary Standridge and Jim Ellis, for missing a check and not having their identifying check stubs. Top bike honors were thus awarded to Bruce Ogilvie and Larry Roesler riding the then new HarleyDavidson SX250. Both Ellis and Standridge still swear they did not cut the course, and even produced witnesses to substantiate their argument. The dispute would not have had the attention afforded it had their disqualification not put a single-seat buggy into 1st overall.

The question of 1st overall opens up yet another can of worms. Neither NORRA nor SCORE pays money or makes any kind of an award for that position. . .only first in each class. But the honor and glory always goes to first spot, no matter what sport you’re talking about. SCORE should inaugurate a special prize for the first vehicle over the line, whether twoor four-wheel. Such an arrangement would also help equalize the purse situation. Since purses are paid out of entry fees and bike entries are traditionally low, the 1st overall bike doesn’t get very much compared to the first cars in each class. But back to immediate problems and yet another controversy that was stirred up when the buggy was awarded 1st place this year. SCORE’S rules simply state that a vehicle must cross the finish line under its own power. You can push a vehicle only 1 percent of the total course, but not through a check or across the start/finish.

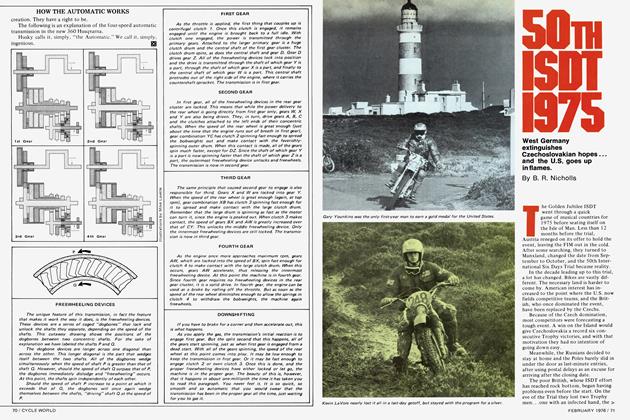

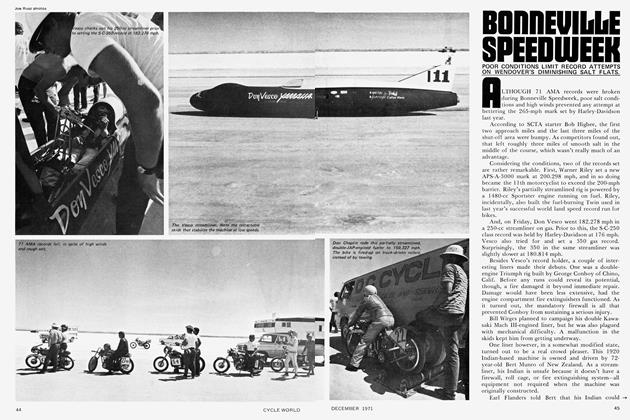

The winning buggy apparently ran out of gas and was pushed an undetermined distance to the finish by a spectator’s truck. It appeared as though the truck actually pushed the car across the line. SCORE’S Sal Fish claims that it was not actually pushed over the line, but was coasting freely. I was standing at the wire and saw the truck right behind the buggy; whether or not they were touching is difficult to answer. I do know that the truck bashed the rear of the buggy just as they crossed the line. One of the accompanying photographs clearly shows the truck crunching under the impact of contacting the buggy. If it was not pushed over the line, just what was happening?

A similar situation occurred at the end of the 1975 1000. The winning Cannady/Baker Honda was pushed over the line by AÍ Baker after a collision with a tree that wiped out the bike’s electrics. SCORE officials wanted Baker to start it, but, of course, he couldn’t. A long discussion about disqualifying the Honda followed and Baker won. Had the bike been disqualified, a storm would have ensued, the end of which would never be heard. The rules say nothing about any machine having to run, merely that it must cross the finish line under its own power. Baker simply coasted it downhill and across the finish.

It was beginning to look as though the old NORRA days were back. That organization was often accused of tuning things so that cars were sure to win. It was big car bucks that kept NORRA alive, and they naturally hated to lose to crummy little bikes. It would appear that SCORE needs to rewrite parts of its rulebook to be much more explicit.

That winning Gene Cannady/Al Baker Honda was prepared by the Baja Honda wizard, Bill Bell at Long Beach Honda. He has been putting together winning combinations ever since the first Baja bikes for Larry Burquist. The current Cannady/Baker bike is a 410cc > XL in a C&J frame.

Baja 75

The 1975 1000 was dominated by bikes right from the start. And most agree it was the roughest and toughest Baja ever. . .which is what you get when you take the racing off the road down there. Mechanical troubles were the order of the day for many, including the Husqvarna-riding teams of A.C. Bakken/ Mitch Mayes and Howard Utsey/Larry Roesler.

Second place overall was taken by another motorcyclist, Malcolm Smith, but in a single-seat buggy rather than on a bike. Malcolm’s switch to cars has done a lot for them. Damn few drivers can run anything as fast as Malcolm. When asked if he’ll ever go back to bikes for Baja, the grinning Smith says no. He feels he has had enough slow healing from bike injuries. The most dangerous thing about driving a buggy is the chance of getting motion sickness, a malady that often plagues Smith.

Desert ace Mary McGee drove a minitruck in the 1000 but didn’t finish because of poor preparation of the vehicle. She finished 33rd on a Husky in the 500, riding alone the whole distance, the last half without working rear shocks. It’s people like Mary, the incredible Dempsey brothers and their Triumph, Carl Cranke, Dick Hansen, Ron Bishop and others-most of whom have been riding Baja races almost from the beginning-who make the unbelievably difficult racing seem almost like fun.

We have been told that SCORE is going to lower the bike entry fee for 1976. Hopefully it will attract more entries. The contingency program is excellent and all SCORE racers are eligible for the annual $ 1 5,000 points payoff. At the conclusion of the 1000, AÍ Baker and Gene Cannady led the competition.

A lot of the glamour, charm and flavor have gone out of Baja racing since the 1000 was made a loop race instead of a one-way event finishing in beautiful LaPaz. It used to be that if a team didn’t have an airplane to carry parts and people to the remote checks like El Arco and Punta Prieta, they didn’t have a chance. Now nearly every checkpoint can be reached by pavement, which certainly makes the race crews’ jobs much easier. For most racers, having the race run back to Ensenada where it began makes Baja running a much more feasible proposition financially.

But many of us really miss the fun of sitting on the porch at the Los Arcos Hotel in LaPaz, drinking Margaritas and watching the sun go down behind LaPaz Bay. CYCLE WORLD’S official Cessna 185 and our ace Baja pilot John McLaughlin followed the action from the air as usual. But instead of sleeping on the ground under the plane, listening to cars and bikes coming through the all-night check at HI Arco, we spent the night in a first-class hotel, completely out of the range of sound from the check at Rancho Santa Ynez.

Our lodging for the night is just one link in the El Presidente chain that now connects such formerly hard to reach spots as San Quentin, Santa Ynez, Punta Prieta, Guerrero Negro, San Ignacio and LaPaz. The Hotel LaPinta in Ensenada is also part of the government-owned chain. Raul Sanchez runs the Baja hotels and he loves motorcyclists and those funny things they ride.

What having that chain of hotels has done for the Baja trail rider is fantastic. It is now possible to drive deep into the interior, stay at a good hotel, unload and ride in country that it used to take days to reach. On the other hand, it is still possible to start in Ensenada and go clear to LaPaz, almost entirely in the dirt. There is still a lot of unoccupied space in Baja and will be for a long time. It isn’t as romantic and adventurous as it used to be, but it is still fun.

Road riders would do well to consider the kind of trip CW editors Bob Atkinson and Randy Riggs took a few months back on the Suzuki RE5. They rode the length of the peninsula, staying at the El Presidentes.

SCORE’S 500 also follows an interesting loop that begins and ends in Ensenada and covers some really rough territory. Much of the terrain it runs over is used in the 1000, as well. Both races are actually somewhat shorter than their names would indicate. Mike’s Sky Ranch is used in both. Though fairly easy to reach since the pavement now extends through the Valle de Trinidad, it is still remote and rustic enough to make a weekend trail ride highly pleasurable.

The Baja 500 always produces some interesting food for thought. . .such as the fact that AÍ Baker and Gunnar Lindstrom, riding a 350 Honda, finished the race in 8 hr., 29 min. Fast, but consider the 1 25cc Penton ridden by Eric Jensen and Carl Cranke that took only 8 hY., 59 min! And if that isn’t enough, the Ogilvie/Roesler 250 H-D took 8 hr., 16 min., thereby winning the top bike class.

Raja bikes are pretty unique too. Power and lightness are, of course, essential, but reliability takes on a whole new meaning down there. Tires are always a problem in racing, but in Baja they often are the biggest difference between winning and being an also-ran. Lighting, too, is extremely critical. Until Cibie developed the 100,000 candlepower light unit presently used by almost all entrants, it was nearly impossible to make lights bright enough. Running at night with huge batteries and several 100,000 candlepower lights is still the main advantage cars have over motorcycles.

(Continued on page 108)

Continued from page 85

When it comes to the kinds of bikes ridden on the peninsula, the built-in reliability of the four-stroke Honda Singles has made them highly competitive with the lighter and usually more powerful motocrossers like the Husqvarnas. In fact, Baja has traditionally been a Honda vs. Husky battle.

Things have come a long way since my first trip to Baja in 1962 with John McLaughlin, the senior and junior Bill Robertsons, Dave Ekins and the guy from the news service who was shooting the Honda advertising stunt for True magazine. Not only did he write an almost wholly inaccurate story, full of melodramatic crap and untruths, but he also threw up on the airplane.

Robertson Jr. and Ekins were paid to ride the then CL350 Honda Twins from Tijuana to LaPaz for the introduction of the bike. It took them slightly more than 39 hours. The record kept getting shorter and shorter as a seemingly endless procession of bike riders and dune buggy drivers kept trying.

Then cars became much more sophisticated. Builders reduced weight, pumped up the engines and found out how to keep them together. On smooth courses they are faster than motorcycles. In the rough, few are as fast as some bikes, damn few are as good as the best bike and rider combinations. If Baja racing continues to be run as SCORE does it now, bikes will probably keep on winning top spot overall. But there aren’t many long-distance riders as good as Cannady, Baker, Mayes,

Bakken, Roesler and a couple of others. If there were, bikes would be taking the first 10 instead of just the first three to five places.

I remember when Bruce Brown first released his movie “On Any Sunday.” Time magazine’s film critic chided Bruce’s awed, unabashed admiration for the motorcycle racing heroes of the film story. I’m happy to admit that I am a great deal like Bruce. The balance, stamina, skill, timing, reactions and all of the other physical, mental and emotional traits required to be the best on a bike just blow my mind.

Baja takes all of that, and something else very special. You might call it determination, but that isn’t strong enough.

It probably means you have to be a certain kind of maniac to survive the rigors of fast long-distance, cross country racing. Baja freaks is what they are, and so am I. I just don’t go as fast. g]