LETTERS

RACERS READ ABOUT RACES

I have just read the October article about the Yamaha Women’s National by Virginia DeMoss. It is so well-written and informative that it was like being in the races again. To have the biggest and best magazine cover the event, linked with the quality of her article, will do more for women’s racing than anything to date.

Lorie Watson Women’s 125cc Champion Santa Ana, Calif.

I wish to compliment Virginia DeMoss on her excellent article on the Yamaha Women’s National in your October issue. Hers is the best and most complete article I have read on the Nationals. You are lucky to have such talent working for your magazine.

I thank you for covering this event. Believe me, the women racers need all the publicity they can possibly get. It’s really a tough road for us.

Nancy Thomas Applegate, Ore.

A WEIGHTY QUESTION

My fiance and I have recently purchased a Honda CB750. We think it’s a great machine, and we really enjoy riding it. We also own a Kawasaki 100 G 4 Scrambler.

Other bikes that we have owned include: Honda 150, Honda CB175,

Yamaha DS6 250, Kawasaki 350 S2. We traded the 350 for the 750 with touring in mind.

The speed limit over here is 50 mph, and fuel is $1 per gallon. That still doesn’t stop us from gearing up almost every weekend and touring around.

Parts for Japanese bikes are hard to get here; we had a prang on the 350 and it was in the bike shop for seven months waiting for parts. In the end we had to get some parts specially made up, because we just couldn’t get them on order.

It’s very hard to get insurance on bikes here; some companies don’t touch bikes at all, others don’t go above the 350cc class. Out of approximately 35 insurance companies in Hamilton, only two were prepared to touch the 750. The premium is $105 per annum.

One complaint that we have about your magazine concerns the specifications for a road test. When you say “Test weight (fuel and rider),” how heavy is the rider?

(Continued on page 14)

Continued from page 10

We’re getting married in October and everyone tells us we’re mad buying a $1500 bike, but we don’t care because we’d rather be on a bike any day than in a car.

Incidentally, we’d be interested in corresponding with other 750 Four owners in the States, to exchange views, opinions, etc.

Lynda Austin 75 Winstone Ave.

North Island, New Zealand

In answer to your question about rider weight, Lynda, look two lines above where it says “Test weight (fuel and rider). There you’ll find the bike’s “Curb weight (w¡half-tank fuel), ” which is the weight of the bike without rider. Simply subtract that figure from the “Test weight” figure and you’ve got the rider weight. But to save you all that trouble, we’ll let you in on a little secret. The rider weight in our tests is always listed at 160 lb., which we’ve found to be a pretty good average.— Ed.

ANALYZING THE SNELL HELMET TEST

This is in answer to the “Up Front” article in the Sept, issue of CYCLE WORLD entitled, “On the Snell Memorial Foundation Helmet Test.”

In the editorial before the quotation from the Snell booklet, the editor states that the purpose of a helmet is to save your life. That is true, but that implies that a helmet can do that and not at the same time endanger your life. Many riders believe that wearing a helmet can cause an accident in the first place, by such things as reduced hearing and vision, and deflection of sound waves. In addition, the helmet itself can cause injuries in the course of the accident. And it is by now well known that certain slight blows on the helmet can cause broken necks where there wouldn’t otherwise be injuries, or perhaps lesser injuries. But the greatest problem with helmets lies in the marginal protection offered at best, which leads to writing helmet standards not at a human safety level but at a level that most helmets can pass! The analysis that follows shows that the test is for only very minimal protection, and that the test is so limited because that is the natural limit of helmets.

The main part of the test standard that I object to is the impact test. A review of the engineering involved and the true results in language that riders can understand, instead of the deliberately bamboozling “J” bit in the standard, will show you the severe limits of the helmet.

The following Snell standard quote is from the article. “For each helmet the calculated total impact energy shall be 100 J as established utilizing the basic drop test mass of head form and supporting arm without helmet, and as confirmed by measured impact velocity.” When I read that I was at first pleased.

But let’s put that J into units we can understand. J stands for Joules. That is a unit not usually used. It is generally defined as 10 million ergs. But it can be converted into units we can understand. One-thousand Joules is 738 footpounds. One ft.-lb. is the energy from dropping one pound one foot. Ten ft.-lb. is from 10 pounds dropped one foot or one pound dropped 10 feet, etc. Just for perspective, imagine dropping 10 pounds three feet on your foot. It won’t hurt too much. But drop 100 pounds from the same height; that’ll hurt and that’s 300 ft.-lb.

One of the previous standards for testing helmets was to drop one six feet with an 8-lb. mock head in it, for a total of about 11 pounds. This gave about 66 ft.-lb. of energy to dissipate. Some helmets didn’t pass. But now the standard talks about 1000 J or 738 ft.-lb. total! You see why I was surprised? Had there been some engineering break-

through on helmet construction? Alas, no. The talk of the 1000 J is hogwash and should have been omitted. We find the test helmet is dropped eight times in four different locations of the helmet, two drops in each location. The two drops in each location are first 140 J, and second 100 J. The 140 J is 103 ft.-lb. The 1000 J is achieved by adding 140 J plus 110 J, and multiplying by four for the four different locations. This gives 1000 J total! But a lot of little bangs is not the same as one big bang. Try knocking your head gently against the wall a dozen times in one place, a dozen in another, for about a hundred little knocks. Each knock can be about one ft.-lb, for a total of 100 ft.-lb. You know that the 100 little knocks is not the same as the one 100 ft.-lb. knock!

So we are back to the one maximum drop of 140 J or 103 ft.-lb. A helmet weighs at most three pounds, so with an 8-lb. mock head we have about 1 1 pounds. To get 103 ft.-lb., the drop is a little over 9 feet. That is some improvement over the old test, but what does it mean in terms of protection?

First, when you leave your bike in an accident, we hope your body is attached to your head. In that case the weight is not 8 lb. for the mock head, but 170 pounds let us say. In the test with a total 103 ft.-lb. maximum, the drop

leads to an impact velocity of 15 mph. But the problem is, that is achieved with a head only, no body. If the body is put on, the impact .velocity doesn’t change, but the kinetic energy does! We have to drop 170 lb. only 0.6 ft., about seven inches, to keep the same kinetic energy. With 170 lb. on the helmet instead of the test weight of eight pounds or so, we must maintain the kinetic energy, since it is the energy that smashes the helmet. With the 7-in. drop and the 170-lb. body, we get an impact velocity of only about 4.5 mph! And that is the limit of helmet protection according to the latest test! I could go on and show you that in order to design the helmet for a 25-mph impact, the helmet would have to be 6 in. thick and weigh 12 to 14 pounds. The material in that 6 in. would have to be carefully designed with energy absorbing honeycomb-type material. Practically, this helmet would be unwearable. We must also remember that even with the older test of 66 ft.-lb., some helmets failed. It is marginal at best that helmets will meet the new test standard that gives you protection—if you weigh about 170 pounds— for about a 4.5-mph impact. Perhaps you now understand why the advent of bureaucratic forced helmet laws has not lead to any overall reduction in fatality rates for motorcycle riders.

(Continued on page 18)

Continued from page 15

Please understand that the purpose of this is not to knock standards for helmets, except when the standard is deliberately put into bamboozling language designed to hide the true limits of protection. A rider is entitled to get the best helmet possible for his money. The problem arises when the helmet standard is written for the limit of the helmet, not from a human safety level, and is compounded when the construction standard is combined with another standard that says a rider has to wear a helmet! When the protection at best is so limited, and there are dangers associated with wearing the helmet, there must be no other standard or law that says we must wear one. The rider—not some Washington Bureaucrat—must decide how to protect the rider’s own head.

Ed Armstrong Fox River Grove, 111.

IMPROVED PARTS PRICES

Erom time to time, prices of bikes and parts change before an issue hits the newsstands. We usually hear about it and have the opportunity to pass the information along to our readers. Here is a letter received from Rokon concerning our test of the 19 76 MXII. —Ed.

It has been brought to my attention that some of the prices in the parts price list of the article were not correct. Following are the items with the prices you listed and the actual retail prices as they should be.

I do hope this information will prove beneficial to your magazine and readers.

Douglas H. Duncan Sales Coordinator Rokon Inc.

ARE YOU LISTENING, HONDA?

Randy Riggs’ trip through the Mother Lode country on the Honda 750F was of great interest; that’s a part of the USA I have not yet had the good fortune to visit.

Riggs’ comments on the machine itself are things I have read many times. . .and I am amazed at the similarity of the annoying things on my new 400F. The snatch in the drive line is frightening, particularly since the Honda dealer from whom I purchased the bike has just informed me that this is a known fault that will hopefully right itself gradually after a few thousand miles. This, of course, is hardly likely, since most kinds of excess free play will tend to get worse.

(Continued on page 22)

Continued from page 18

The vibration Mr. Riggs mentions is all the more annoying, I think, because of the very high speed of it. Between 3500 and 4500 rpm it is felt, on my machine, through the bars and renders the rear view mirrors useless. At 5000 rpm it makes itself felt through the seat and footpegs also. Surely Honda’s engineers could do something about this. . .Norton’s Isolastic system comes to mind immediately, of course. And I seem to remember riding English Ariels before the Second World War whose handlebars had hard rubber bushes where they were attached to the forks, thus eliminating some of the shakes.

It really is a shame because otherwise I think the 400F is a super little bike. But I consider the two aforementioned defects quite serious. Somehow or other I shall find a way to control the throttle so that I may scratch myself with my right hand without resorting to holding it with my left. I wonder if the English models have a throttle stop screw (not that I would dream of looking when I go to England in November. . .or then visiting a spare parts department. . .).

It would also appear that Honda does not want us to use Halogen lights because a 6.5-in. headlamp is pretty hard to convert. The handbook that comes with the 400F can also be a little confusing by quoting a fuel tank of 3.7 gal. and a reserve tank of 0.8 gal. Now is the 0.8 included in the 3.7, or does the tank actually hold 4.5 gal.? Who knows. The eight lines allocated to the break-in procedure are also delightfully vague. I quote: “The first 600 miles should not be operated in excess of 80 percent of max rpm in any gear.” So, with the redline at 10,000 rpm, it is being suggested—not to old know-it-alls like you and I, of course, but to new motorcyclists—that 7500-8000 rpm is okay for running in. Heh, I just thought of something, maybe that’s how the transmission snatch arrives in the showrooms straight off the engine test bed in Japan.

Best wishes and thanks for telling it as it is. Come next March, with no improvements, you will see me at Daytona on my trusty 1972 380 Suzuki. It took me down and back this year, so I think I’ll hang on to it just in case. By the way, do you think Honda reads letters to the editor?

Maurice Willson 0 New York, N.Y.

LET US HEAR FROM YOU

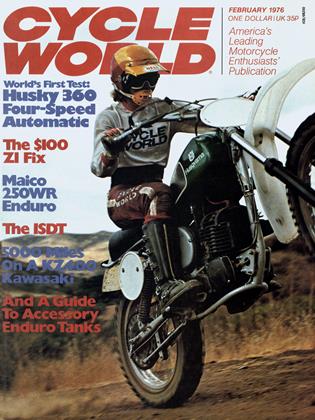

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

February 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

February 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

February 1976 By Joe Parkhurst -

Competition

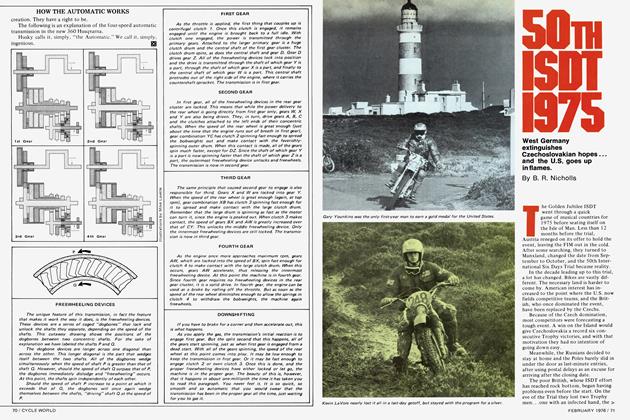

Competition50th Isdt 1975

February 1976 By B. R. Nicholls -

Competition

CompetitionBaja Racing 1975

February 1976 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

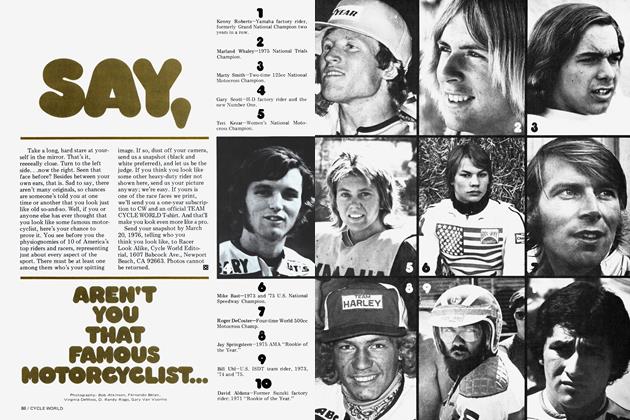

FeaturesSay, Aren't You That Famous Motorcyclist...

February 1976