ROAD RIDING

BASIC STREET RIDING MANEUVERS

DAN HUNT

(Continued from last month)

STOPPING

There are several things to note about different motorcycles’ slowing and stopping characteristics:

1. Four-strokes have the engine compression braking that you normally associate with any kind of driving. Turn off the gas and the engine helps to slow the machine. If your bike has a two-stroke engine, you don’t get the engine braking effect. You’ll find therefore that a two-stroke is initially more difficult to learn how to ride fast through the turns. It really curls your hair the first time you enter a turn too hot with a twostroke, and snap the gas off. Nothing happens, except that it gets very quiet, and you just keep on goooiiiinnnnnggggg! That’s why braking technique, smooth technique, is very important with the new breed of highperformance two-strokes available today.

2. The damping and firmness of a motorcycle’s suspension can greatly affect your braking technique. Production motorcycle design is a trade-off between comfort and handling. The most common inadequacy of street machines is the tendency to exhibit excessive frontend dive when you hit the brakes hard; this is disturbing because it throws the rider forward and may reduce his control. Front-end dive may be caused by the sheer weight of the machine itself, light springing of the front forks for comfort, or inadequate compression damping of the front fork unit (which may sometimes be improved by switching to a slightly heavier grade of fork oil). Another factor in front-end drive that is not often considered is the lack of rebound damping at the rear, or too soft a spring rate at the rear. When a soft rear spring “unloads” as the weight shifts forward in braking, it will rebound over a greater distance than a stiffer spring and therefore cause a greater forward displacement of the machine’s attitude. Undamped, that rebound occurs annoyingly fast and steepens front-end dive.

(Continued on page 86)

Continued from page 84

If the machine’s rear shock absorbers have spring tension adjustment capability, you can help minimize a dive problem by selecting a one-notch-harder setting than normal. Don’t automatically select the hardest setting available, particularly when you’re riding solo. Do remember to select a slightly stiffer setting when you’re carrying a passenger.

If you become a fanatic about handling, you may want to experiment with high-performance rear damper units, or alternate spring inserts and oil weights for your front end. But, if you’re new to your bike, wait awhile until you have lived with it and have come to understand exactly what you need in the way of modifications. New damper units are expensive, and you have to know what you want to get the desired result. The same goes for front fork modification; confine your experiments at first to small changes in fork oil weight, and, if it doesn’t feel comfortable, return quickly to the original.

3. Motorcycle gearboxes have much to do with the smoothness of the downshifting process, with the prime factor being the gaps between each gear ratio. The five-speed gearboxes provide the smoothest changes, because the spread between gears is so narrow that it’s relatively harder to make mistakes. But even they can provide opportunity for screwing up. The most noticeable offenders are the Japanese gearboxes and some of the Italian gearboxes that have inordinately large gaps between first and second gears. The result is that you’re between following a well-learned engine-sound gear-speed pattern while downshifting from fifth or fourth back through second. Then comes the shift from second back to first. You free the clutch, blip the throttle and kick it into first. Back out goes the clutch and all of a sudden the back wheel chirps as you realize that you didn’t get the engine turning quite fast enough. It’s frustrating, but you can’t do anything about it, except hopefully remember next time to crank it faster.

To finish off the basics, let’s briefly discuss turning a motorcycle. It should be self-evident that a motorcycle turns only when it is banked. But the subtle relationship between the turning action of a motorcycle and its starting and stopping action is not so evident, judging by the appalling number of people who fall off for seemingly no reason.

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 86

The limitations as to how fast you may turn a motorcycle have to do with a) the angle of bank it may achieve before its pipes, undercarriage or centerstand hits the ground, b) how “sticky” the tires are, c) the condition of the road surface, d) the capability of the suspension, e) the amount of throttle being applied, f) the amount of brake being applied, and g) the position of the rider’s body in relation to the lean of the motorcycle.

The factors involving the dragging of pipes or centerstand, and the traction offered by the tires are self-explanatory. The factor of road condition should be, too; if the road is wet, oily, sandy, bumpy, ripply, rocky, torn-up, muddy or otherwise not dry, smooth or clean, you ought to know enough to lessen your

attack on any given turn; you don’t go into the turn as hot, and you don’t bank the motorcycle quite so far.

Throttle application is a little more subtle. In the hardest and fastest of turns, a small amount of throttle application will offer you greater control than just allowing the bike to freewheel, or indeed rolling the throttle off entirely. Freewheeling, or snapping the throttle off, tends to straighten the bike because rider and machine weight is thrown forward.

On the other hand, jerky acceleration through a turn, or simply too much throttle in a steep bank, may result in the back wheel breaking loose. This is particularly true with today’s high-performance machines; you simply do not wrench the throttle open in the middle of a turn. Rather, you dial it on slowly, just like you would try to tune in a hard-to-find station on your FM stereo. Just before you reach the limit, you’ll be able to feel the back wheel drifting slightly.

Keep in mind that if the road surface gets suddenly worse in the middle of such a fast turn, you have to back off from the limit. This doesn’t mean snapping the throttle shut; instead, roll it off smoothly and at the same time lighten up your angle of lean. My advice here presupposes that you have the sense to

scan the turn in advance of entry so that you know the road condition and that you don’t “shoot” turns that you can’t see in their entirety before you reach them.

The newer riders should rule out hard braking in the middle of turns until they feel comfortable with their machines and with their own advancing capabilities.

Instead, brake before the turn and concentrate on accelerating smoothly through the turn. This technique, carried to refinement, will yield consistently fast times through most turns anyway. The reason that you avoid heavy braking in the turns has to do with one simple axiom that you should always remember: braking compromises turning ability because of its tendency to overcome traction and shift the weight of the bike forward and outward; likewise, turning decreases braking ability because it vectors the pressure of the tire against the ground outward rather than downward and thus reduces traction.

EMERGENCY AND ADVANCED MANEUVERS

Motorcycle riders soon discover that when they get into crisis situations, the body keeps telling the mind that it ought to stop moving entirely. And preferably not by running into something solid.

(Continued on page 92)

Continued from page 88

The mind is the prisoner of the body. And thus it gets trapped into doing all sorts of stupid things. Reflex action, instinct, fear, blinking, freezing: they’re all instinctive. And you need to overcome the most dangerous reactions of instinct.

Success comes through practice. But it also comes from your state of mind. You can get extra practice by imagining yourself in an emergency situation and mentally rehearsing the disciplined rider techniques that are necessary to get you out of trouble. Commonsense, analysis and a basic understanding of the way a motorcycle handles are your best tools. Ritual behavior or doing something because you heard somebody tell you that’s the cool way to do it can get you into trouble.

I used to have a friend named Charlie who went trail riding back in the days before people even wrote books and columns about riding technique. Every other week he’d come back from the desert and tell me how he “threw his machine away.” To explain, “throwing it away” means that if you don’t dig what’s happening, you jump off your machine and let it continue on without you. This, I suppose, was a half ritual and half reflex trade-off that Charlie had worked out for himself. I’m not so sure that he was as much concerned with being near a crashing machine as much as he was with the admiring “oohs” he could get when he returned to tell his friends that he ditched his bike in mid air. What is more rewarding than the reaction: “Wow, heavy, man. You stepped off.” Suffice it to say that I never learned much about riding from Charlie.

To road riders such as we are, stepping off isn’t one hell of a neat alternative. Road bikes, left to their own devices, get scratched, bent and broken very quickly. And due to the flatness of the riding surface, their riders usually end up going the same direction as the bike itself, either ahead, alongside, behind, on top or underneath the machine.

Therefore, there are only two real alternatives when trouble threatens: you straighten it out or you don’t. The logical conclusion—and I can’t emphasize it too strongly—is that all your effort in a troublesome situation should be devoted to coming out of it smoothly and in control of your machine. Your mind isn’t going to function properly if, when threatened, you preoccupy yourself with whether you will or will not crash. That kind of split second speculation takes valuable time away from the thinking and action needed to save the situation.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 92

Now, let’s set up a scheme for coping with trouble. First you must realize that the majority of emergency situations that you’ll encounter on a motorcycle involve only a very limited range of possible response.

These are: 1. Stop the machine. 2. Slow the machine. 3. Keep the machine upright. 4. Change direction.

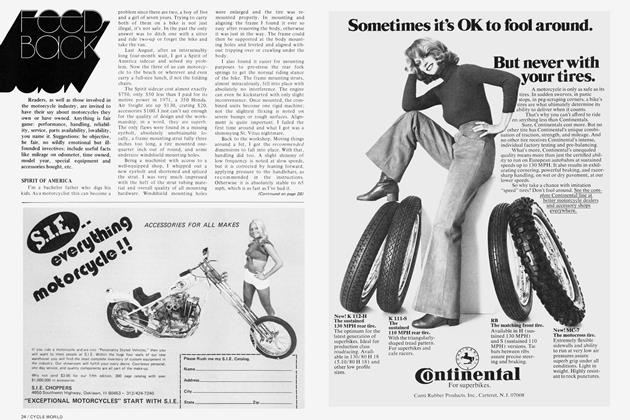

Situations in which stopping/slowing the machine is the proper remedy are by far the most common. For these situations, one axiom should be remembered: A motorcycle stops or slows best when it is perpendicular to the ground, i.e., when it is not banked into a turn.

Here’s an example. Morris Mountainreider decides to cut a few hot ones around his favorite hilly back-country road network. Gracefully weaving a rapid string through the mountains, he miscalculates the approach to a hard lefthander, and the rock wall looms high in his future.

He knows he’ll run wide at his present speed and angle of bank. He feels that if he maintains speed and increases angle of bank, his kickstand will ground and send him flying. What does he do?

If he maintains angle of bank and hits the binders, it is possible that he could get slowed down. But it’s tough to bring off. Braking action, you’ll remember, lifts the bike and tends to make it go straight. And chances are that traction was so marginal when the situation began that the added force of braking may cause immediate and total loss of traction.

By far the best and most reliable corrective action in this situation is to lessen or eliminate entirely the angle of bank, and then apply full braking force. The sequence is: Throttle off.

Straighten the bike first. Do not attempt to shift down or squeeze the clutch. Full braking force. Machine slowed to safe speed. Lighten braking action and resume turning. Resume light throttle to hold bike into turn.

A good way to remember the sequence is by use of the phrase, “Straighten and brake.” The beginning of these two actions should take no longer than it takes to say those three words.

(Continued on page 96)

Continued from page 94

Note that you’ll be trading a small amount of roadway for your increased ability to brake in a straight line. The trade-off is worth it in most situations, assuming that you were anywhere within five feet on either side of the proper approach to the turn.

Make sure that you get the bike up straight before you apply full braking force. When it is straight, you get on the brakes smoothly right up to the limit of your ability.

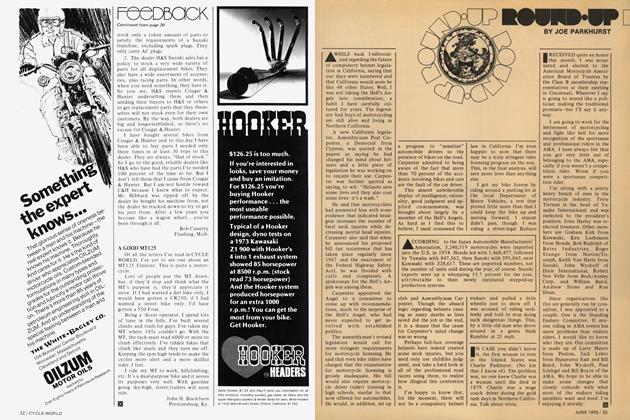

For pointers, watch road racers who overcook the entry to a turn off a hot straightaway. Daytona is the classic example, especially turn one. They arrive at 140 to 170 mph. The turn itself requires slowing to 40 or 50 mph, as it changes direction in a decreasingradius one-eighty.

It’s easy to misjudge or run out of brakes. When it happens, the rider comes sailing off the straight like a rocketship. “Omigod, he’s going to. . .! But he doesn’t. Instead, the bike cuts an anticlimactic line straight to the outside of the turn. And the rider is squeezing the brakes for all they are worth. A few run onto the grass at the outside, but the riders who straighten soon enough end their flight going about 20 mph. Only the ego is bruised and they’re stabbing back into first gear, ready to get back into the fray.

I strongly recommend that you do not attempt to downshift in this rapid braking maneuver until the bike is safely through the turn. Adding the downshifting sequence causes complexity in an emergency that needs to be reduced to its simplest elements. Operation of the clutch to downshift unlocks the back wheel from the rotating force of the engine. As a result, 95 times out of 100 the back brake will lock up, causing loss of control and loss of time while you lighten up on the lever to regain traction. And, if you hurry, you could catch a false neutral position between gears and really be surprised!

We have tried alternate methods of slowing down. Best braking performance—i.e., stopping in the shortest distance—occurs when the rider does only one thing. . .slams on the binders. If he has time to whip the clutch in just before he is totally stopped, or bang off four classy downshifts, that’s fine, but it adds stopping distance. If he’s late and thus kills the engine, that’s better. He stops shorter. A stop is a stop; and a rock wall is a rock wall.

More emergency and advanced maneuvers next time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue