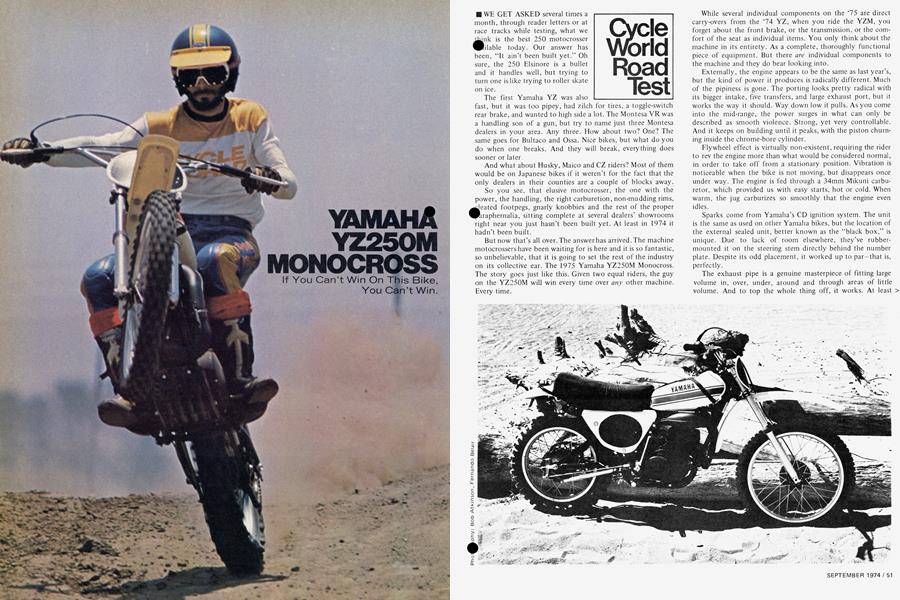

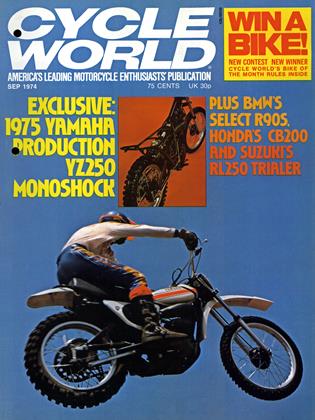

YAMAHA YZ250M MONOCROSS

If You Can't Win On This Bike, You Can't Win.

Cycle World Road Test

WE GET ASKED several times a month, through reader letters or at race tracks while testing, what we

think is the best 250 motocrosser available today. Our answer has been, "It ain't been built yet." Oh sure, the 250 Elsinore is a bullet and it handles well, but trying to turn one is like trying to roller skate on ice.

The first Yamaha YZ was also fast, but it was too pipey, had zilch for tires, a toggle-switch rear brake, and wanted to high side a lot. The Montesa VR was a handling son of a gun, but try to name just three Montesa dealers in your area. Any three. How about two? One? The same goes for Bultaco and Ossa. Nice bikes, but what do you do when one breaks. And they will break, everything does sooner or later.

And what about Husky, Maico and CZ riders? Most of them would be on Japanese bikes if it weren’t for the fact that the only dealers in their counties are a couple of blocks away.

So you see, that elusive motocrosser, the one with the power, the handling, the right carburetion, non-mudding rims, pleated footpegs, gnarly knobbies and the rest of the proper paraphernalia, sitting complete at several dealers’ showrooms right near you just hasn’t been built yet. At least in 1974 it hadn’t been built.

But now that’s all over. The answer has arrived. The machine motocrossers have been waiting for is here and it is so fantastic, so unbelievable, that it is going to set the rest of the industry on its collective ear. The 1975 Yamaha YZ250M Monocross. The story goes just like this. Given two equal riders, the guy on the YZ250M will win every time over any other machine. Every time.

While several individual components on the ‘75 are direct carry-overs from the ‘74 YZ, when you ride the YZM, you forget about the front brake, or the transmission, or the comfort of the seat as individual items. You only think about the machine in its entirety. As a complete, thoroughly functional piece of equipment. But there are individual components to the machine and they do bear looking into.

Externally, the engine appears to be the same as last year’s, but the kind of power it produces is radically different. Much of the pipiness is gone. The porting looks pretty radical with its bigger intake, five transfers, and large exhaust port, but it works the way it should. Way down low it pulls. As you come into the mid-range, the power surges in what can only be described as smooth violence. Strong, yet very controllable. And it keeps on building until it peaks, with the piston churning inside the chrome-bore cylinder.

Flywheel effect is virtually non-existent, requiring the rider to rev the engine more than what would be considered normal, in order to take off from a stationary position. Vibration is noticeable when the bike is not moving, but disappears once under way. The engine is fed through a 34mm Mikuni carburetor, which provided us with easy starts, hot or cold. When warm, the jug carburizes so smoothly that the engine even idles.

Sparks come from Yamaha’s CD ignition system. The unit is the same as used on other Yamaha bikes, but the location of the external sealed unit, better known as the “black box,” is unique. Due to lack of room elsewhere, they’ve rubbermounted it on the steering stem directly behind the number plate. Despite its odd placement, it worked up to par—that is, perfectly.

The exhaust pipe is a genuine masterpiece of fitting large volume in, over, under, around and through areas oí little volume. And to top the whole thing off, it works. At least you’d think so by the amount of power that the engine is delivering to the rear wheel. But the engineers who worked on it, figuring in volume, shape, primary and secondary pressure waves and the rest of the technical gumbatch, were probably ready for the rubber ranch when they finished. What a headache it must have been!

The frame that surrounds all of these power-producing mechanics is of thin-wall steel tubing. The traditional Yamaha double cradle is still incorporated, but the single backbone is only half its normal length, splitting into two smaller diameter tubes at about the middle of the fuel tank area to make room for the shock absorber positioning required by the monoshock arrangement. But that’s a whole story in itself. The chassis is strong and we had no problems at all with it.

Brakes, which have been consistently great up front and consistently overly sensitive in the rear on Yamaha motocrossers—YZs included—are great all around on the YZM. The front binder is progressive, powerful, and capable of being locked up if the brake lever is really clamped tight. It is a half-width binder, identical to Yamaha’s regular 250 MX hub, except for a magnesium backing plate. It is all very light.

The touchiness has been removed from the rear brake. It now plays a very substantial part in bringing the machine to a quick halt. Feedback throughout the pedal is strong and precise. You can use the brake to set the machine up in controllable drifts, or merely to reduce speed for an approaching turn.

The hub is full width, although visibly hollow in the half opposite the magnesium backing plate. Yamaha prefers this arrangement because it keeps the rear wheel light, like a halfwidth hub would, yet provides the additional strength of wide triangulation and shorter spokes.

Styling is also new this year. The YZM comes with an attractive red, white and black paint scheme. The wide red stripe on the white tank runs horizontally along the side below the Yamaha logo and is flanked by a thin black stripe both above and below. The side panels ,are white with black number plates.

Both fenders are white plastic items and each is unique in its own way. The rear one is just a stub. It does little more than protect the rider from debris being scattered about by the rear tire. The air box, housing twin fuzz/foam elements, acts as the lower part of the fender. And a rubber flap, hung from the seat, works with the movement of the monoshock assem bly to protect the rest of the machine.

Up front is a new two-piece fender that can be set up for either dry or wet track conditions. The mud-deterring frontal section attaches with four short screws and can be removed to leave a very normally shaped dry weather fender.

We’ve made it clear before that we don’t care much for Dunlop motorcross knobbies. Whether it’s because of the rough, hard tracks that abound in Southern California, or simply because Dunlop knobs aren’t as pronounced as other tires’ are, thereby not being able to achieve as good a grip, we’re not sure. They just don’t work well for us.

The YZM sports a set of Dunlop knobbies and, as objective as we try to be, we began our test with minds prejudiced against the tires. Well, you live and you learn. They work great. In particular, the 4.60-18 monster shod on the rear. What a traction delivering behemoth that thing is. It has knobs as wide as suitcase handles down the center, with smaller grippers all around and well up the sides. The front tire is a regular 3.00-21, but it too holds when asked.

YZs have traditionally been tall bikes. Even the regular production motocrossers sat higher than was felt to be right. The YZM is no exception. It isn’t too hard to keep the bike upright when sitting, as long as you’re taller than 5 ft. 10 in.

Shorter riders will have to lean the bike slightly to one side. Get the machine moving though, and you forget about the height as everything falls into place.

Even the handlebars, which feel wide at first, don’t bot^a. you at all. If they do, they can be quickly modified with a saw. The aluminum levers are easily reached by the average hand and they even come with grit covers. Handlebar shape is ideal for sitting (which you’ll be able to do much more on this bike than ever before), but slightly short for taller riders when standing.

The transmission is what you’d expect from Japan. Perfection. The Orientals knock out slick-shifting gearboxes with boring consistency. If there is any hang up with the trans at all, it’s in the incredibly short throw. It seems like all you have to do is think about the next gear and there it is. The purpose of the short throw is to reduce the time required to shift. Remember, this is an all-out racing machine. >

The shift lever is knurled and tends to cause blisters on the big toe from using too much pressure when shifting. You can’t slam shifts around with the YZM. Just kiss the lever ^th the tip of your boot and it’s already done. Old CZ riders ™11 probably dislocate their left knee the first time they ride a YZM. Ratio selection is perfectly suited to the power characteristics. There are many times when you can even take a turn one gear higher than normal, thanks to the smoother power

of the “M”.

Suspension is magnificent. The forks are identical to those on last year’s YZ. Seven inches of slightly stiff, but welldamped travel, which loosens up after the bike gets used a while. The rear end, though, is where the magic lies.

The swinging arm pivots from a standard position, inside the engine bay. But that’s where any similarity between conventional swinging arms and the monoshock ends. Sprouting from each side, at what would normally be the lower shock mount area, is a secondary fork mounted at a 44-degree angle from the swinging arm.

Five inches from its origin, vertical cross braces connect the secondary rear fork with the primary fork, the swinging arm. Both sides of the secondary fork merge several inches in front of the rear tire, where they form the lower pivoting mount for Éhe single shock absorber.

^ The shock body bolts to this mount and runs under the frontal portion of the seat and the rear section of the fuel tank, terminating in a rubber-mounted, stud-bolt arrangement just shy of the steering head.

The shock itself is odd looking. It is a gas/oil unit that has an accumulator at the base of the shock body, which is nothing more than an aluminum casting. Inside the middle of the casting there sits a neoprene membrane, which keeps the oil separated from the pressurized gas. There is no air at all in the main shock body. It is all oil. Here’s why.

In a regular shock absorber, the oil and the air mix. Air bubbles get into the oil and when these bubbles pass through

the orifices in the damper rod, damping is momentarily lost. Yet a certain amount of air is essential in a regular shock to compress as heat expands the hydraulic fluid.

In the monoshock, when the piston assembly’s action causes the oil to heat and expand, it merely pushes against the membrane, which, even though it is holding back 250-280 psi of compressed gas, compresses the gas even further. Damping never falters from oil frothing. Damping characteristics may be changed by having the dealer alter the pressure against the membrane. The tension of the solitary spring is pre-set at the factory and cannot be changed, although different rate springs will be available.

There is no measured capacity for the monoshock assembly, since servicing instructions merely say to “fill until full.” However, Yamaha’s racing department acknowledges that it takes between 250 and 300cc of fluid to fill the shock body. That’s quite a bit of oil, so damping fade due to overheating should never occur. Also, the aluminum accumulator dissipates heat quickly, keeping things cooler.

The compressed gas used is nitrogen. There are two basic reasons why it was used in place of simple compressed air. One is that nitrogen is less susceptible to expansion under heat than air is. If the pressure on the membrane were to change too much because of the heat caused by a long moto, damping characteristics would also change. The nitrogen sees to it that this doesn’t occur.

The second reason that nitrogen is used is one of safety. If, for some reason, pressurized air slipped past the membrane and became mixed with the oil, what you would have is a petroleum fuel (oil) and oxygen (air) mixed under tremendous pressure. The membrane pressure, in conjunction with the pressure created in the oil itself when the piston moves through the shock cylinder, could cause this combustible mixture to detonate through diesel action. The shock absorber would explode. Since nitrogen is an inert gas (i.e. it will not burn), there is no possibility of this happening.

The shock assembly allows 6.3 in. of vertical wheel travel, although the rear axle actually travels in a 6.56-in. arc. Imagine, more than six-and-a-half inches of movement at the rear axle. That’s just a half inch less than the front forks!

Sitting on the YZM in the CYCLE WORLD garage, it felt lousy. Not only was it tall, but the suspension felt rigid. The rear end in particular. It took two people sitting on it before it would give at all. And when you got off, it topped out as though there wasn’t a single drop of oil in the shock body.

But this was all new to us and we didn’t know that that’s the way it is supposed to feel. So be warned. When you go to your local Yamaha dealer to check out the YZM, it’s going to feel stiffer than a fresh garage door spring. But enough of this technical jazz, how does the thins ride?

It rides like it has wings. No bull. It takes the nastiest series of bumps, potholes or whoopers you know of and turns them into gelatin. You find yourself entering familiar turns much faster than you ever have before, due to the fact that you could cover the preceding choppy straight at greater speed and in more control of the machine.

No longer is it necessary to look for the smoothest line. Go for speed, friend. The fastest way is the best way and to hell with the holes and bumps. You don’t feel them on this bike. The monoshock turns a torturous MX track into a rough scrambles track, taking lesser courses and converting them into dusty road race circuits.

Steering is just as good as the suspension. The Yamaha goes where it is pointed. On tighter turns, it wants to be powered in, pivoted, and then blasted out. A simple squaring off procedure.

On fast, rough sweepers, the suspension really comes into play. Because of the great travel and superior damping, which keep the rear tire in contact with the ground, the bike can be powered over such obstacles with nary a twitch or wobble. No sliding around; no tendency to high side; no rough ride; no fighting the steering. Point it, gas it and set up for the next one. If you want to “Class C” it, the Yamaha will oblige. But to be really impressive, slide it over potholes and ripples. No one will believe what they see.

Jumps are a gas. Fly high and far if you like. Landings are predictably straight and soft as a whimper. But don’t jerk up on the bars. The front end is so light that you can loop the bike if you’re not careful. Couple this lightness in the front to the powerful engine and the deadly traction that the monoshock and the Dunlop tire provide, and you’ve got a set-up whereby the height of the front wheel is determined solely by the right wrist.

If there is a fault in the suspension, it is in the rear, and occurs only on downhills where the power cannot be applied. Because most of the combined weight of rider and machine are carried downhill on the front end, there is very little pressure being put on the rear suspension unit.

Under these circumstances the rear end behaves no better than a conventional dual-shock arrangement. Actually, that should be amended to “no better than the best dual-shock arrangement.” If course layout permits, and if you’ve got the hair, try downhilling under power as often as possible. The application of power will torque the rear suspension into working and will make the ride a much smoother and decidedly faster one.

So what we have is a suspension assembly that produces more than 6.5 inches of travel, a large oil capacity to maintain viscosity for more controlled damping, and, thanks to the approximate 1:1 ratio of wheel travel to shock travel, a unit that will no doubt outlast any of the trick set-ups now available.

Nothing is absolutely perfect, however, and this includes

the Yamaha YZ250M. The machine has its share of shortcomings, although we’re admittedly nitpicking. The grips belong on a wheelbarrow. The entire exhaust system must be dismantled in order to be removed.

It is possible to burn your right leg on the exhaust pipe if you slide forward on the seat when cornering. But sliding forward is useless, since the Yamaha can be ridden just like a Maico; by putting your rump in one place and keeping it there for the whole race. The back edge of the rear seat is slightly sloped and not comfortable at all, which is the exact opposite of the rest of the seat.

The exhaust note is harsh and you may be required to silence it further before some promoters will allow you to race. The front fender hits a spring tab on the junction of the header pipe to the first expansion cone.

The rear tire wears rapidly and the choke mechanism consists of a frustrating little stick that must be grasped between two fingers and pulled straight up, then turned to lock into position. The weight they saved by eliminating the choke lever g^a joke in comparison to the difficulty caused by its absence. ™t there are other things that Yamaha has done to pare weight off this racer that show much more forethought.

The fork legs are machined down and holes are drilled in every piece of the motorcycle where they do not affect strength or function. Magnesium side cases are used. Both the clutch hub and the shift plate have been “Swiss cheesed.” Chrome moly is used for the handlebars. There is no oil injection. The beautifully-shaped fuel tank is aluminum. The seat base is fiberglass. The primary sprocket and external clutch actuating mechanism have been relieved of their cover. And the list goes on.

Yet in spite of all the work that has gone into making the

YZM light, it still tips the scales at 232 lb. with a half-tank of fuel. That’s 19 lb. over last year’s YZ. The increase in weight is the price you must pay for the monoshock set-up.

The swinging arm, because of its configuration, weighs nearly twice as much as the previous one did, and the massive, single shock absorber outweighs a pair of Thermal-Flows by about 2:1. The machine could be fabricated lighter by utilizing chrome moly tor the frame and magnesium for the inner engine cases. But then you would be talking about a $3000 motocrosser rather than one that comes closer to being reasonably priced, although it is still high.

So the next time anyone queries us about which machine is the best motocrosser you can buy, we’ll have a definite answer. For all the reasons it has taken these many pages to list, the 1975 Yamaha YZ250M Monocross is the best motocross machine presently available. By a mile. ra

YAMAHA YZ250M

$1850

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHigh School Motocross—A Little Hope And A Lot of Ifs.

September 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

September 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

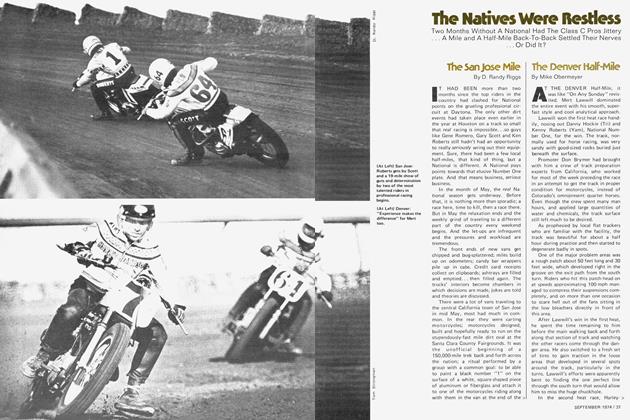

The Natives Were Restless

The Natives Were RestlessThe San Jose Mile

September 1974 By D. Randy Riggs -

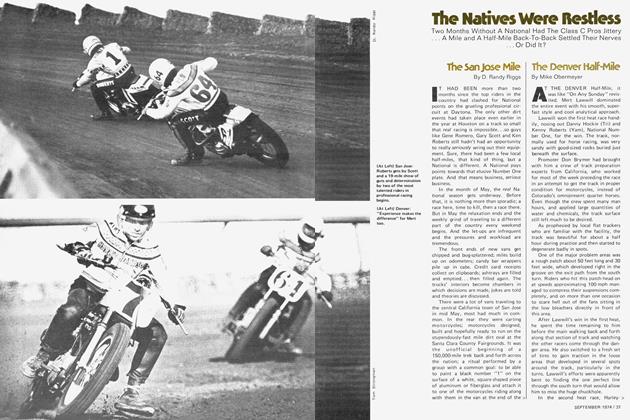

The Natives Were Restless

The Natives Were RestlessThe Denver Half-Mile

September 1974 By Mike Obermeyer