BULTACO METRALLA, SHERPA AND TSS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

SPAIN'S BULTACO MOTORCYCLE is the most faithful servant and companion to the traveling adventurer since Don Quixote’s Sancho Panza. We began to think so in June, 1962, when we tested the Bultaco TSS 125cc road racer, and we have just had that opinion considerably reinforced by our experiences with a trio of 200cc Bultacos: the Metralla sport/touring; the Sherpa scrambler; and again with a larger-engined TSS. At the time of that first test, the Bultaco was a relative unknown here in America. Now, after 18 months of exposure here and after winning numerous sporting events all over the country, Bultaco is acquiring a widespread and excellent reputation — and the machine deserves every good word that will be said about it.

Basically, all of the Bultacos are the same. The frames, suspensions, brakes, and all of the mechanical elements have a great similarity. Yet, by incorporating detail differences in the models we tested, the Bultaco’s makers have made each of the three outstanding in its particular field.

The Bultaco engine is a single-cylinder, piston-port two-stroke which has little in its primary specifications that would suggest an outstanding design. However, outstanding is precisely the word for this engine. It is both light and powerful, and is very attractive in appearance — although we suppose that shouldn’t count for much. The cylinder head and barrel are made of aluminum alloy, as is the crankcase (which is in unit with the transmission casing) and the finning is deep and very closely pitched. Cooling should be effective even under conditions of warm weather and hard riding — which is what the bike gets a lot of in its native Spain.

All of the engines have hand-worked porting. The transfer passages are cast into the aluminum cylinder, as are the intake and exhaust ports, and these are hand fitted to match windows cut into the cast-iron cylinder liner. It is possible, in theory, to perform the various porting operations with the necessary precision on a massproduction assembly line, but somehow errors always seem to creep in unless you can have skilled craftsmen adding the final touches.

Instead of the usual through-bolts, extending down through the cylinderhead and barrel to the crankcase, the Bultaco engine has short studs on the crankcase by means of which the cylinder is pulled down securely and more studs in the top of the cylinder that provide an attachment for the cylinder head. There are 7 studs holding the cylinder to the crankcase, and 6 up at the cylinder head. No head gasket is used, which means that the liberally finned cylinder head can draw heat from the barrel and help in keeping it cool. Also, the arrange-

ment makes it quite impossible to blow a head gasket. There are several advantages to the head and barrel fastening system, but most important is the fact that it leaves the cylinder free to expand upward, and that will minimize distortion of the cylinder as it heats and cools. With all-iron cylinders, this point is not so important, as the iron cylinder and its steel through-bolts expand and contract at about the same rate. In other all-aluminum engines, it has been found necessary to make the throughbolts of light alloy as well to avoid distortion problems.

The cylinder head is a fairly interesting item. It has an inverted bathtub combustion chamber, surrounded by a large squish area. The squish area makes it possible to employ high compression ratios without detonation, and the shape and location of the cupped combustion chamber tends to capture the fresh mixture as it squirts up from the transfer ports and hold it, swirling, in the top part of the cylinder. Charge loss is reduced in this manner.

Down in the crankcase, the Bultaco engine is much like any other single-cylinder two-stroke. The crankshaft is built-up, with separate full-cycle flywheels and a pressed-in crankpin. The crank’s mainshafts run in ball bearings; the connecting rod's big end has double-row roller bearings. A plain bronze bushing is used at the small end of the connecting rod in the Metralla and Sherpa engine, as this type bearing is adequate for the kind of service for which those engines are intended. The TSS on the other hand, is subjected to prolonged fullthrottle, maximum (or nearly so) speed conditions and in earlier TSS engines there were occasionally problems with small-end bearing failures. To counter this, the TSS engine is now equipped with needle roller bearings, and that has eliminated the problem.

One feature of the Bultaco engine’s lower end assembly is the use of very small flywheels. This makes the crankshaft volume small, which is essential to good breathing, and it also reduces the primary flywheel effect to such an extent that low-speed torque and tractability could suffer. Too-light flywheels have caused problems in other engines. However, the Bultaco engine has additional flywheels outside the crankcase, and the inertia of these, added to that of the main flywheels, successfully smooths out the power impulses.

The left-hand outer flywheel serves extra duty as a part of the dynamo. Magnets are cast into the flywheel and, as they rotate, they induce a current in low-tension coils. One of these coils feeds through a set of points and a separate high-tension coil to provide a spark for ignition. The other^ is the source of current for the bike’s lighting systems. No battery is provided; lighting current comes directly from the dynamo. Actually, only the Metralla has the lighting current coil - it is omitted in the Sherpa and TSS.

Power is transmitted from the engine to the transmission by means of a single-row chain and sprockets (providing a primary reduction of 2.37:1) to a clutch that looks far too small for the job. But, this particular clutch has a torque capacity all out of proportion to its size. The clutch’s pressure plate has 6 coil springs, and pulls together an 11-plate clutch element, with all-metal plates. The clutch in the TSS we tested some 18 months ago was similar in construction, but had a terribly sharp take-up. This later model can be eased into engagement as smooth as silk (if we may be permitted that time-worn expression).

The Bultaco’s transmission is in some respects like that of an automobile — to the extent that the drive comes in at one end and goes out the other. Top gear is direct. Internal ratios vary between models, and a 6-speed gearset is available for the TSS. But, the factory contends that the engine’s power range is wide enough to make the 6-speed transmission unnecessary, and we are rather inclined to agree with them.

An advantage of the Bultaco’s transmission layout is that it leaves the transmission output sprocket exposed. This makes for rapid and easy changes in overall gearing, and that is certainly worthwhile. Our only complaint is that the output sprocket is deeply shrouded inside the casing, and it is virtually impossible to thread in a replacement chain without first removing the left-side engine/transmission case cover. The job has been made much less of a bother on the Sherpa, which has the cover trimmed away around the sprocket to give improved accessibility.

All three frames, of the Metralla, Sherpa and TSS, are made of small-diameter steel tubing, with the extensive use of sheet steel gussets where the tubes join. The assembly is welded together and, frankly, this is the one place where the finish is not very good. The welds are puddled on in a most unlovely manner, and while it appears that the welders have gotten sufficient penetration to insure strength, they have not laid down the kind of even bead that Americans have become accustomed to seeing. Also, the gusset plates have a trifle too much of the hand-hammered look, and their edges retain the slightly ragged finish that was created when they were hack-sawed from blank stock. Even so, we will have to concede that the frame is strong, and rigid, and there is no denying that it is also very light. Those attributes go a long way toward offsetting its lack of beauty.

Telescopic forks for the front wheel and swing-arms for the rear constitute the suspension system. All three models look very much alike, and like most other modern motorcycles in this respect — but there are important differences. The Metralla’s forks have the axle mounting eye at the bottom of the fork legs, and slightly ahead of the leg centerline. The TSS is just about the same, but has the mounting eye positioned higher on the fork leg, so that the effective height of the forks is reduced and the machine can be built lower. Also, the damper is somewhat stronger. Finally, the Sherpa forks have the axle eye right down at the bottoms of the fork legs, and that gives the maximum “reach,” while simultaneously bringing the wheel back a bit to increase “trail.” All of the forks are constructed in roughly the same way, with steel legs and light-alloy sliders slipped over the lower ends of the legs. The TSS has exposed springs. Those in the Sherpa are housed in the forks and the exposed section at the top of each fork has an accordion-type dust cover.

The entire brake assembly is virtually identical for the trio. About the only difference is in the Sherpa’s backing plate, which is of the solid, dust-excluding type; the backing plate on the Metralla and the TSS have a big cooling air scoop cast on. There was no difference we could detect in the rear brakes. Of course, the brakes are rather large for such a light motorcycle, and they have finned aluminum drums for heat dissipation, so braking performance is exceptional — even on the TSS, which has brakes that work very hard at times.

Although the TSS had no provision for kick-starting, the Metralla and Sherpa had a dandy little lever that, while odd-looking, will really spin the engine over. The kick lever leans forward, and the “peg" punches back out of the way, instead of swinging, in the conventional fashion. So, to get it into action, you have to pull the peg out in position, and pull the lever back against a light spring pressure until the ratchet engages. Then, if you are either sufficiently left-footed, or arc standing beside the bike, you can pump the engine over furiously until it starts. At no time while we had the Metralla and the Sherpa did they require much prodding before coming to life. And, the TSS would run-and-bump start with little pushing. It is a fine two-stroke that always starts without a struggle.

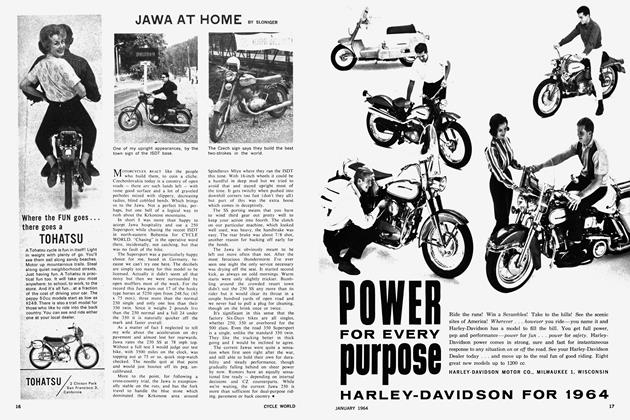

The Metralla proved to be one of the nicest smalldisplacement bikes for all-around sports riding we have ever had. The position it imposes on its rider is a trifle crouchy for extended trips, but it really teels great when indulging in fast riding back on twisty mountain roads. The performance was nothing short ot phenomenal. Despite having only 200cc of displacement, and handicapped (in a sense) by very tall gearing, the Bultaco Metralla turned in a standing-quarter time and speed that would do credit to a machine of twice the size. Just as important, it was entirely without temperament. 1 he engine would pull smoothly from any speed (almost) and it displayed no bothersome periods of vibration.

In the area of handling, the Metralla was really outstanding. In fact, it approaches being as good as the ISS — and that bike is great. The steering is quick and sensitive, although not excessively so, and you can lean the bike until the foot pegs drag without it getting all quivery.

The appearance of the Metralla was another good point. It was finished in a very attractive combination of greys, light and dark, and the overall neatness ot the machine, with the colors, was enough to make the average motorcycle enthusiast begin to salivate a bit.

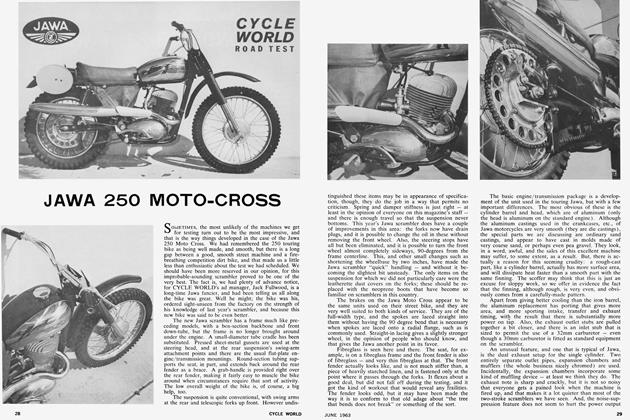

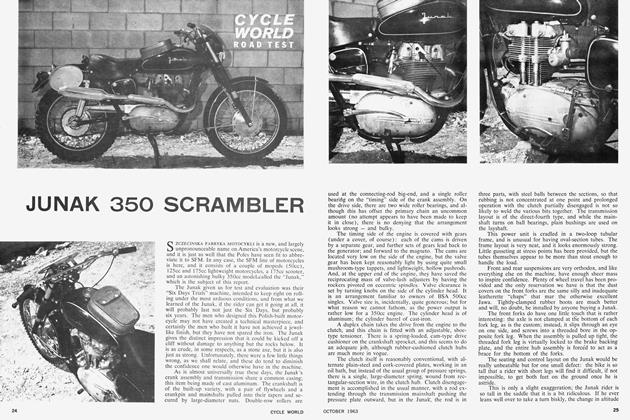

The Sherpa shared the Mctralla’s attractive appearance, but that is not its most outstanding characteristic, and that is not what it will be bought lor. What the Sherpa has to offer is simply superb handling, bags of power, lightweight and the ability to run slow or fast. Most scramblers, if they have enough power to be competitive in their class, have engines that are too radical to be run at anything much less than lull throttle. I he Sherpa, by contrast, can be ridden almost like a trials machine, with the engine virtually at an idle. 1 hen, if the rider hooks on a big handful of throttle, he will find that this engine, which will purr like a kitten, is also capable of yowling like a tiger. You can crank it on just about any time, in any gear, and send up a rooster-tail of dirt and gravel behind the rear tire.

Do not assume, from all this talk about low speed torque, that torque is all the engine has. The Sherpa’s engine has a useful power range that extends past 9000 rpm. Somehow, in the combination of porting and exhaust system (the latter item is much like the one used on the TSS), Bultaco’s engineers have produced a two-stroke that runs like Jack-the-Bear at any and all speeds, and without a trace of fussiness. Because of the engine’s output characteristics, and the bike’s vice-free handling, the Sherpa truly is suitable for both expert and rank amateur. The expert will find that the Sherpa has the steam and handling to give him plenty of speed. And. the novice will appreciate the fact that the Sherpa can be ridden gently until he can become proficient at pounding along in the dirt.

The Sherpa is most at home over relatively smooth terrain, where there are no huge bumps and the speeds are high. The suspension travel is a little short for encounters with small boulders. We would have liked it a bit better if the seat and handlebars had been raised about 4 inches, but apart from that, it was everything we could ask.

Apart from being instrumental in giving the engine a wide range of power, the expansion-chamber exhaust system served another useful purpose in taking some of the edge off of the exhaust note. Two-strokes tend to have a sharp, crackling exhaust noise, and when amplified by an open megaphone, this becomes an annoyance for everyone. The Biiltaco’s expansion-chamber system is no muffler, of course, but it does subdue the racket to a limited, but much appreciated, extent.

With the other dirt-oriented modifications in the Sherpa, the wheels are fitted with tire security anchors: one for the front wheel; two for the rear wheel. These anchors give a positive location for the tire, and prevent the tire from rotating (which will often pull the valve stem from the tube) when running hard with relatively low tire pressures. And, incidentally, the Sherpa has beautiful, light-alloy racing wheels — as does the Metralla and the TSS.

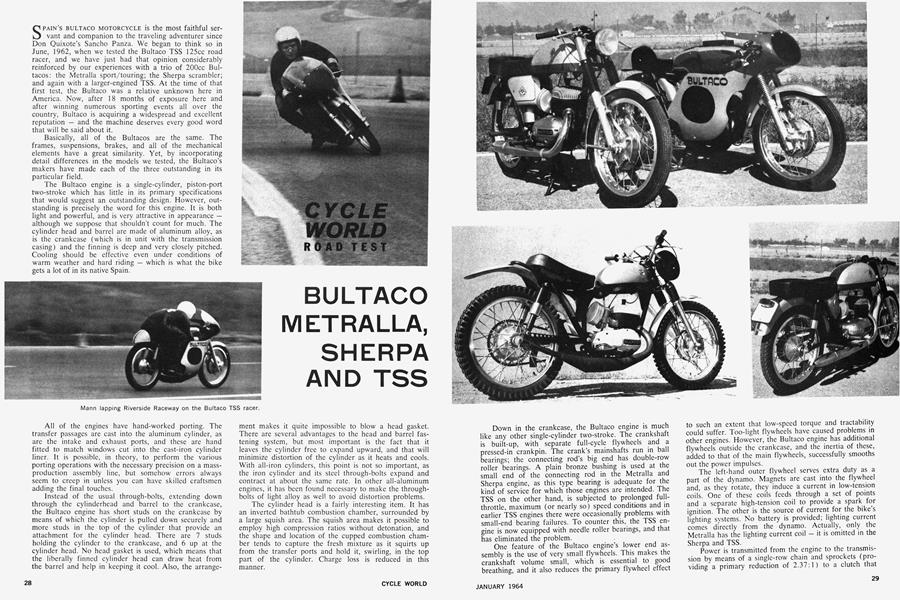

It was nice to renew our acquaintance with the TSS. We had enjoyed riding the 125cc engined TSS before, and the 200cc version proved to be more of the same only with more power. With the gearing available, the top speed of the TSS 200 was limited to just over 100 mph (107 to be exact) but the relatively “low” ratio gave the bike a lot of rush coming out of corners.

The handling of the Bultaco TSS is so good that it all but defies description. Because of the very low weight, and ultra-responsive steering, the bike will feel somewhat unsteady to a first-time rider, but after you have been aboard for a few laps and become accustomed to the machine, it steadies down and becomes a pure pleasure. The suspension feels a touch too stiff, probably in the damping, for running at high speeds over a rippledsurface, but it is otherwise absolutely superb.

Braking performance is always critical in road racing, and the TSS was superb in this department, too. The brakes are not overly large, by road racer standards, but they do the job in a way that brooks no criticism, being both smooth, light and extremely powerful.

We got an unexpected bonus, when testing the TSS, in the person of Dick Mann. He came out to assist, in whatever manner we might want, and to watch the proceedings with Phil Cancilla of Cancilla Mtrs. in San Jose, Calif., Bultaco distributors in the West (along with Bultaco Western). This was for us an honor, as Dick Mann is an uncommonly skilled rider, and articulate (he can explain what to do and why you do it as well as anyone we know). Also, Mann has won the Grand National Championship, and will be wearing the coveted number one in the 1964 season.

As a matter of fact, Mann did give us his thoughts about road racing, and some riding pointers (which we probably aren’t skilled enough to put into practice) and he did the riding while we timed the Bultaco for top speed.

It is difficult to express just how much we liked the Bultacos. All three do their particular job most impressively, and all three are well finished, nicely styled and priced competitively. With regard to the prices, we should mention that those shown in the data panels are FOB Los Angeles, and the Bultacos can be purchased for slightly less in the east due to differences in shipping costs.

BULTACO METRALLA

SPECIFICATIONS

$685

PERFORMANCE

BULTACO SHERPA

SPECIFICATIONS

$725

BULTACO TSS

SPECIFICATIONS

$995