The Kawasaki Dixie National, alias Road Atlanta

When Roberts Does It, He Does It In A Big Way

John Waaser

KAWASAKI PUT its name on the Road Atlanta race again this year, but they're having trouble making it stick, in spite of all the publicity they got from the track announcer and the program. One problem may have been that, for the second year in a row, they didn’t win the event.

So, while they got the big local splash as the Kawasaki Dixie National, throughout the rest of the country the question was, “Are you going to Road Atlanta?” And among true road racing enthusiasts, it is perhaps meet that this event should take its name from the course, still one of the finest in the world.

One of the primary items of pre-race interest to road racing fans was the presence—or lack thereof—of the HarleyDavidson water-cooled 250cc machines. H-D was wetting peoples’ lips with brochures, but the machines were nowhere in sight. They just hadn’t been able to bring 25 of them into the country in time for this one.

They’ve apparently set a price of $3395 on the bike, including fairing, Dunlops, gearing and spare parts, and at that price they’ve had some interest. It’s clearly competitive price wise, and Kel Carruthers let slip a remark that he felt it would be “a better bike than the Yamaha, if only because it was designed from the ground up as a road racer, not a street bike.” It certainly will be easier to maintain than a Yamaha, thanks to its separate cylinder barrels and removable gear clusters.

Just how soon it will appear on the circuit is anybody’s guess, but the Harley van did take on a load of 3.25 and 3.50-18 racing slicks from Goodyear, and you just know they don’t use those on the XLR750s!

Just about as trick as the 250 Harleys promise to be was Ron Pierce’s approach to the Yamaha exhaust pipe problems. Ron had picked up his bike after Daytona, and had paid more for a used machine than most people paid for a new one. He turned it over to Mack Kambayashi, a West Coast tuner of some repute, who spent about 60 hours just fabricating a set of pipes to cure the factory’s splitting problems.

The two center pipes cross over and under each other, and are virtually round in cross section. But the outer two pipes are almost as slab-sided as the factory stock units, to absolutely prevent grounding. That they do not touch is evident from the scrape marks high up on Ron’s fairing. But the right pipe did fracture during the race, and a replacement set will be made up with a more round profile.

The factory Yamahas sported pipes designed by Kel Carruthers, who scoffs at printed reports that the European bikes ran so well at Daytona because they had experience with the pipes. First, of course, had the Europeans

come up with anything really good, the factory could have drawn from their experience in building the production bike.

Kel insists that his pipes do not draw from either the factory or the European pipes. He has routed the left pipe up and over, in the style initiated by Suzuki, and copied first by Kawasaki.

This leaves room for a three-pipe system underneath, with two of them exiting on the right, one on the left.

The cones are still not perfectly round, with the outside ones triangulated in a downward direction, and the center one pointed a bit at the top, for a close fit between the other two. He could go a bit more round, too, but the pipes seemed to hold up well.

Other solutions to the pipe problem included Kevin Cameron’s two-into-one system on the Boston Cycles machine ridden by Jim Evans, and the heattreated pipes used by Mel Dinesen, both of which have been publicized in the Daytona reports.

Ron Pierce took the opposite approach when he took his machine to Mack Kambayashi. He figured that regardless of how much power the stock bike had, some guys would be hotting them up anyway, so he told Mack to give him as much power as he could.

Perhaps the most unusual solution of all was found by John Long. “What do you do to keep your pipes from cracking,” I asked. “Bless them,” John replied with a straight face. And it must work, as he finished the race. Those who claim to have made a study of the problem say that the pipes are good for about 180 miles if left stock.

They finally managed to run off the qualifying heats for the combined event late Saturday afternoon. Gary Nixon had noticed some ominous sounds coming from his Ed Fisher Yamaha—which Suzuki permits him to ride in the lightweight class. After rebuilding the engine Saturday night, they pushed the bike to the line so Gary could make the legal “attempt” and start the final from the rear.

It was Gary Fisher who got the drag racing start, something he’s famous for, > but he had no practice on Friday and insufficient time to set everything up on Saturday. The bike was too rich, and suffered from some front end chatter in a trick double disc brake that his wrench had built for it. “Overkill,” snorted another rider.

And his engine was brand new too. They would tear it down later and file fit the pistons and things to let it rev freely for the race. Sometimes it doesn’t make much difference; this time they hoped it would. Jim Evans noted that Gary really slowed for the corners-possibly because of the front end chatter.

Ron Pierce had snatched the lead by the end of the first lap, and just started stretching it little by little. Ron had built his own 250, and he was really pumped for the lightweight race, in which many observers felt he had a good chance of an outright win.

Ron is apparently poorly thought of by some of the brass at Yamaha, possibly dating back to when he was a brash young kid trying his hand at road racing. An outright win over the factory bikes would have done his head a heap of good. Ron won the heat, about 4!A seconds ahead of Jim Evans, who had grabbed 2nd on the last lap. Mike Clarke, Gene Romero and Gary Fisher finished out the top five.

If you’re getting the impression that there weren’t many “shoes” in the first heat, you’re right. Nixon didn’t start, Don Castro was severely injured in a dirt race and didn’t show, and Gary Fisher was off song. That took care of the first three grid positions. Romero is pretty heavy, and that puts a penalty on the lightweight bikes. We’d have to wait until the final to see if Ron could compete with Kenny Roberts.

Ken had the pole in the second combined heat; he and Wes Cooley, one of your hotter juniors, streaked away from the start. But it started raining lightly along the front straight, and the red flag came out immediately. We all know that the AMA has a policy of racing in the rain whenever possible, so why did they stop it so soon, when the back of the track was clear?

The Atlanta track is set smack dab in the middle of that red Georgia clay, which is extremely slippery when wet, and that blows fine dust over everything when dry. Any track but this one they’ll run in the wet, but this one is just too dangerous. Everybody waited around a bit, and things did dry off, so they restarted the heat. And again it was Roberts and Cooley first away. But the experts quickly pushed Wes back a couple

of places, and he blew a shift to lose two more later.

Ted Henter came by in a tight dice with Roberts for the lead, followed by John Long. Roberts picked up a couple of seconds on Henter, who had 1 2 seconds on Long. Doug Teague picked up 4th, while Billy Labrie, the guy who usually rode under the same blanket you could have covered Henter and Long with in last year’s Junior races, worked to 5th at the finish.

Many felt that there was still time to run the Novice heats at this point, but the weather was threatening, and officials scheduled them for the next morning.

We arrived at 8:30 the next day and expected to see practice underway. All we could see were some guys painting a duck on the side of the first aid shack.

It seems that the car drivers had been referring to the first aid crew as “quacks” for so long that they had decided to adopt an appropriate insignia.

Bill Payne said he had been there at the appointed hour of 8:00 a.m., and nobody said anything about a riders’ meeting. There was a flurry of activity at 9:45 . . . more than an hour after practice was supposed to start. Phil McDonald had gotten his leathers on earlier, so he was first to the gate for practice. Following a short practice, they would attempt to run off the Expert heats before the 1 1:00 deadline.

Shortly before 10:30 I went out to the esses to get some photos during the heats, and just as I got set up, the announcer’s voice boomed, “Did you ever have one of those days when nothing goes right?” Seems Mark Brelsford’s bike had popped an oil line and left a trail of oil in the third turn.

The oil looked just like a skid mark, said many riders, and they didn’t know what it was. Phil McDonald felt his front end sliding, but he managed to save it. Art Baumann wasn’t so lucky; his mechanics would have a heap of work to do before the final.

The announcer explained that it would take at least half an hour to clean up the oil, and by then they’d be into the silent period. Not even one heat could be run off until 12:30. It was about this time that the sun came out, though, so the weather would be good for the rest of the day, and if everybody really got their act together, maybe they could pull it off. This gave everybody a chance to get their bikes in order for the heats, but pity the poor guy who blows something in the heat; he might never make the final.

By 12:30 there was a sense of emergency in the air. Everybody knew that they’d have to cooperate if the thing was to come off, and even the officials realized that they’d have to keep things rolling. They’d run the Expert heats, then the Junior final, then the National,

then the Novice final, and finally, if light permitted, the combined final. There’d be no Expert semi, no Novice or Junior heats.

Baumann flubbed the start of the first heat badly. He started to cross the line early, so he backed off, then the flag fell, he popped the clutch . . . and bogged the engine as the field flew around him. On the first lap it was Roberts, followed by Fisher, then Romero, Canadian Jim Allen, Hurley Wilvert and Gary Scott.

Scott started dropping back, and finally pulled off in turn two of the fifth lap. By the second lap, Romero had passed Fisher, and Roberts had a huge lead. By the fourth lap, Gene had closed a bit on Kenny, Cliff Carr was well back in 3rd, and Baumann had worked to 5th. A couple of laps later,

Art passed Cliff for 3rd, and the finish had Kenny three seconds up on Gene, who had another 12 seconds on Art the Dart, who was trailed by Carr and Fisher.

The second heat saw first-year Expert Phil McDonald, who had already attracted a fair amount of favorable attention this weekend, soar into 4th place off the line from a third-row start. But the more established Experts quickly pushed him back as far as 10th for a few laps; he finished 9th.

Ron Pierce owned the lead all the way-but again, the only factory stars behind him were Nixon, Smart and DuHamel. All the rest of the top talent had been in the first heat. Steve McLaughlin was hounding Ron all the way on the Mel Dinesen Yamaha, and the announcer was going wild over 3rd place.

Here was Dave Aldana, folks, riding the hell out of this bloody Norton, and isn’t it incredible that a four-stroke could be up so far? Those who knew the truth were riding the lone limey in thq press booth unmercifully. Norton had released Dave from his road racing and short track commitments so he could find a more competitive ride, and he was mounted on a Yamaha Four. Somebody should have told the announcer.

David is not known as a road racer, but like his fellow member of Team Mexican, Don Castro, he’s capable of turning in an impressive performance on the asphalt whenever he has a competitive mount under him. His battle cry for the weekend seemed to be, “Remember Talledega!”

Before the heats, riders had been given one lap to warm up their tires prior to going all out in the heat. Would this practice be continued henceforth? Well, if it offered peace of mind to the riders, it left the tuners with some misgivings, since they would be regridded at the two-minute mark, and the tuners didn’t like the idea of getting the engines up to racing temp and idling them

(Continued on page 84)

Continued from page 66

for two minutes.

So the idea would be evaluated following this weekend, and a decision made as to whether to continue the practice at future events. But the general consensus seemed to be that if any rider didn’t want to take such a lap, he could pull off, then fire up and grid while the others were warming up their tires.

During the heat, due to the late running, Jim Evans had suffered the sort of problems dreaded by wrenches. He had popped a stud, which caused a water leak, and his rear tire, a soft-compound Dunlop, had worn to a frazzle. Boston Cycles’ Bob Fairbairne and Kevin Cameron pulled the top end, extracted thj^ old stud with an easy-out, replaced t^P stud, reassembled the top end and replaced the rear tire with a harder compound one. . .all in 27 minutes. Bet they got a bonus for that. Well, maybe not a bonus, but apparently John Jacobson didn’t want any of the prize money, so Evans split it 50 percent for himself, and 25 percent for each of the tuners. How’s that for incentive to get the bike back on the track.

While they were doing that, the Juniors were doing their thing on the track. Daytona winner Pat Hennen streaked away from the pole position to build a safe lead on his Ocelot Engineeringsponsored Yamaha (a switch this year from Suzuki), but reportedly seized on the twelfth lap. This put Larry Bleil in line for the victory, with eight seconds in hand over a battle between Jay Livingston and Randy Cleek, joined for^^ part of the event by Tommy Byars ai^ Wes Cooley.

The very personable Cleek will be the first to tell you that he’s no road racer— though he excels at short track—but when Livingston overcooked it, Randy inherited 2nd on his Team K&N Yamaha. Byars is the son of a Suzuki dealer, but he, too, rode Yamaha. . .to 3rd place. Cooley wound up 4th.

Leon Cromer came out of retirement to do battle on the George Vincenzi Ducati, and finished 19th. That doesn’t sound like much, but it was just one place shy of being the first non-Yamaha, a dubious honor that fell to Henry Degouw on a Kawasaki.

The first row of Experts had one of the cleanest starts ever witnessed. Nobody jumped a hair. As the first wave cleared, and the second wave roared by, you could hear a distinct difference.

Here were all the four-strokes. Just a^^ there have been no Gold Stars and no G-50s for some years, even the fourstroke multis are now shunted to the second wave, if they qualify at all. Let us make sorrowful lamentations, with great gnashing of teeth, and maybe the AMA will raise their displacement limit so the new BMWs and Kawasakis can compete. Then there was the matter of whether or not it was bent. They had no jig on which to check it, but if they fixed it and Gary tried it out on Saturday and found it squirrely, there would be no time to prepare the back-up machine. They checked the wheel alignment and it was out, but the bike had been fitted with variable eccentrics at the top of the fork tubes to vary the rake a hair.

(Continued on page 86)

Continued from page 84

By the first lap, Kenny Roberts was in the lead and pulling away. Gene Romero was in 2nd. “My job is just to hold the rest back,” said Gene later. Nixon had a slow start, and at this point Aldana was in 3rd, followed by Pierce, Baumann and McLaughlin.

Nixon was working his way up toward the front, though, and in one lap he passed three of the above to take 4th. Cliff Carr had come up behind McLaughlin, and two race-long battles were about to begin. Well before the mid-point, Nixon had passed Baumann too, and come up to do battle for 2nd with Romero.

Baumann had a secure 4th, while McLaughlin was again on his way to the top privateer slot. At the same time, he had to fend off a determined Cliff Carr in a battle for 5th, which was just as close, if perhaps not as hectic, as the battle for 2nd. So if Roberts was steadily cruising away from the field, there was still some exciting racing behind him.

Nixon might have come here expecting to battle for 1st, instead of 2nd, but the special bike that Erv Kanemoto had spent so much time on, and that Gary distinctly preferred, had been lost on an oil slick on Friday. Ken Roberts also went down on the same slick, while a^P witness reports that Phil McDonald came on the slick at a much more critical time, and avoided a crash. Nobody had an oil Hag out, and Roberts and Nixon were looking elsewhere.

Kanemoto was prepared to stay up all night if necessary to right the number one bike, but pieces like the front fairing mount were different from those on the rest of the bikes, and they had no spares. Assuming that the heats would be held on time Saturday-they weren’t, of course—he’d never be able to get the bike ready in time.

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 86

They had not checked the alignment after adjusting the tubes just before Gary crashed. It was possible that they had thrown the alignment out while doing the fork adjustment, so they still didn’t know for sure that the chassis was bent. More importantly, they didn’t know for sure that it wasn't bent, so rather than take chances, they prepared the backup bike.

It was on this bike that Gary was hounding Gene, and the two of them swapped places several times a lap.

“Poor Old Nixon, he didn’t want to get beat,” said Gene. They were even on the back straight, but coming down the hill to the last turn, Romero had just enough of an edge to block Nixon in the last turn. They crossed the line only inches apart, and Nixon reportedly flashed an obscene gesture at Gene as they took the flag.

Romero told friends at supper, “I thought there was a good possibility that Art would get 2nd.” The next day Gene said, “I fell down six times yesterday and never hit the ground.” That, folks, is racing.

During the last turn it was obvious that some bikes were wobbling more than others. Roberts was rock steady.

So were Romero and Nixon. The Harleys were dancing just a bit, though they’re known for good handling. Some bikes were really going badly through there. When you sorted out later who was looking good and who was looking bad, one of the common factors was that, by and large, the better-handling bikes were on Goodyears, while the evil-looking ones wore Dunlops.

Dunlop had switched from their old triangular pattern to a rounder one, with very sudden shoulders. Steve McLaughlin had a contract with Dunlop, but they reportedly told him to run the Goodyears if he liked them better. He did. Ron Pierce was on Dunlops. While he was in 4th place early on, and felt that he had an adequate motor he blamed the tires for his drop to an eventual 10th-place finish.

The Boge shock people have been really good to Ron, and they bought him a set of Goodyear treadless tires, but it was so close to race time that he couldn’t get them mounted. He says he’ll be on Goodyears at Loudon.

In the lightweight class, the situation was reversed. Goodyear had shown up with treadless tires based on last year’s 350cc Yamahas’, and they weren’t working on the 250s. If you didn’t have a Dunlop in the lightweight class, you might as well hang it up. Goodyear hopes to have their tires dialed in for the lightweight class by Laguna Seca.

(Continued on page 90)

Continued from page 88

On the subject of tread versus treadless, Goodyear people say that any time the road isn’t completely covered with water, you’re better off with the treadless tires. Only when all of the voids in the pavement have been filled with water, and rain actually covers the highest spots on the pavement, will a tread prove beneficial. Tires without the tread grip better and wear longer, so you can go to a softer compound and still finish the race. It wasn’t too long ago that people laughed when Goodyear showed up at the races. “Oh they’re a good tire for a novice. They cost a bit less you know. . . .” The shoe’s on the other foot now.

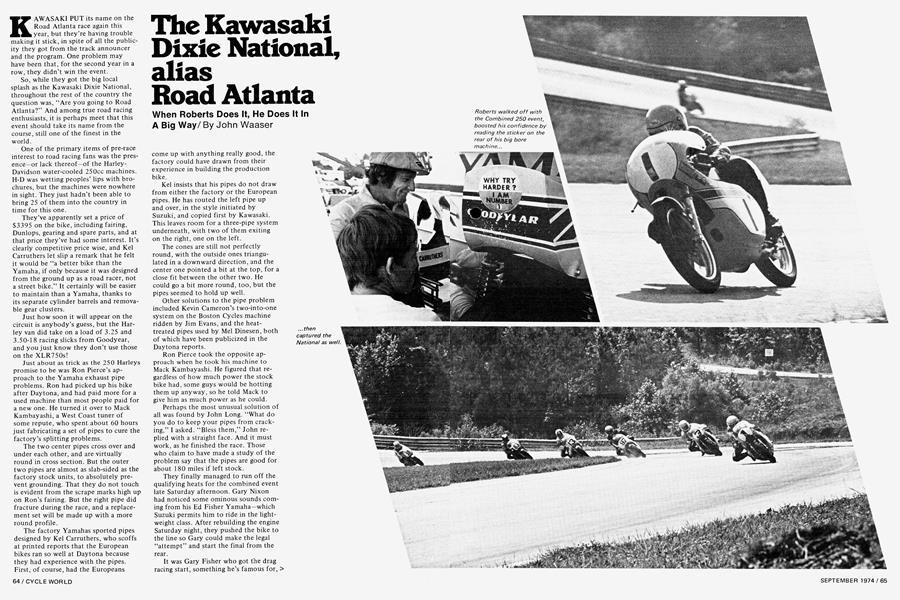

Somebody asked Kenny in victory lane if he had slowed down in the later stages, with his victory virtually assured—he won by half a minute. But Ken replied that every time he slows down, he breaks concentration and gets in trouble. He rolled at competitive speeds throughout the race, but probably had a couple of seconds in reserve case his lead were really threatened.

Before the start of the Novice race, Dave Despain, the AMA’s affable public relations man, was taking a lot of static about the size of the field. Because of the lack of heats, they had decided to line up the entire field. I doubt that anybody really knows how many riders were out there, but there were 113 entries, some of which were no-shows, and the official results were carried to 64 places.

Three waves were used. “Hey Dave, how are the guys who are gridded under the Coca Cola bridge going to see that start flag?” Some Novice riders felt that they had been cheated. Cliff Guild, for instance, was a late entry and started near the end of the third wave. Had he ridden a heat, he might have been able to move up substantially, perhaps even to the first wave. Cliff works for Gary Nixon and is a proven race winner. Because there were no heats, the Daytona winners were gridded at the front, and they blasted into the lead.

Skip Aksland had the lead—a slim one—over Dale Singleton and John Volkman. It was your basic Daytona winner’s circle replay. All three of them got into that wide verge one lap, and Aksland, whose teammate Mike Devlin said they were riding the “most expensive 250s on the track,” failed to make it round the first corner.

(Continued on page 92)

Continued from page 90

Come the last lap, Singleton had the lead, and glanced around under his armpit, saw nothing, backed off and sat up as he approached the checkered flag. A typical Novice stunt, right? Where had Volkman gone? Right behind the other shoulder, of course. John held the gas on and slipped inside Dale for the win by a nose. This time, though, the win was clear-cut, and the official winner was declared before the victory circle pageantry, so John basked in the limelight that had been denied him at Daytona.

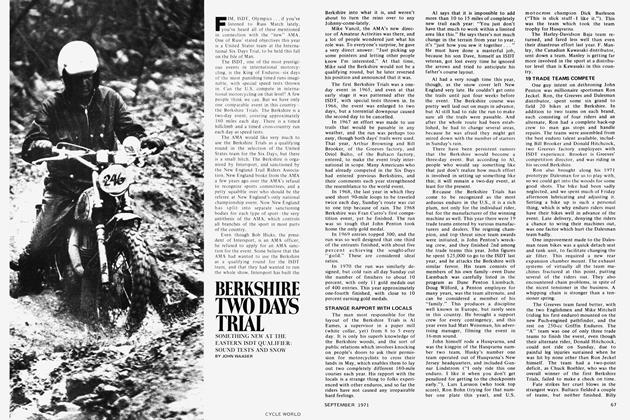

The lightweight feature was almost anti-climactic. Pierce’s heat had been a little slower than Roberts’, and Ken did have a little motor on Ron. Ron said he got stuck behind Ted Henter off the line, and Ted was dragging a shift or brake lever in the corners. By the time Ron got around, Ken had about a seven-second lead, which he held without trouble until the last few laps when Ron started whittling it down to size.

Jim Evans put his Yamaha into 3rd early on, and that’s how they finished.

The most exciting racing of the event was provided by last-place starter, Gary Nixon, who stormed through the back markers. But he still was losing ground to Roberts, and he finally parked it after overrevving it and hearing some strange noises from the newly-rebuilt engine.

Wes Cooley was the first Junior; he took 10th place. So this event, for a change, didn’t even come close to living up to its promise of exciting racing.

In victory lane, Roberts revealed that his temp gauge had been up around 1 10 degrees centigrade, which is very, very hot. They normally run around 80-85 degrees. So Ron might have caught Kenny had the race been longer. Then he might not have, either. Ken’s problem might just have been the gauge, and had Ron been scrapping for the lead, Ken might have been inclined to turn the wick up a bit and see what happened. So for Ken Roberts, it was an easy double, and a neat points cushion toward his second National Championship. jo]

RESULTS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHigh School Motocross—A Little Hope And A Lot of Ifs.

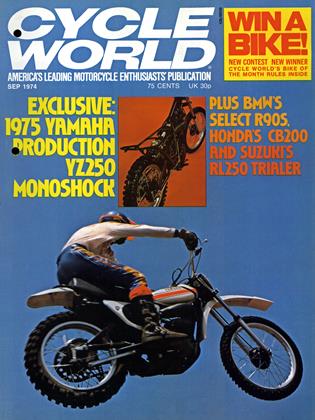

September 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

September 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

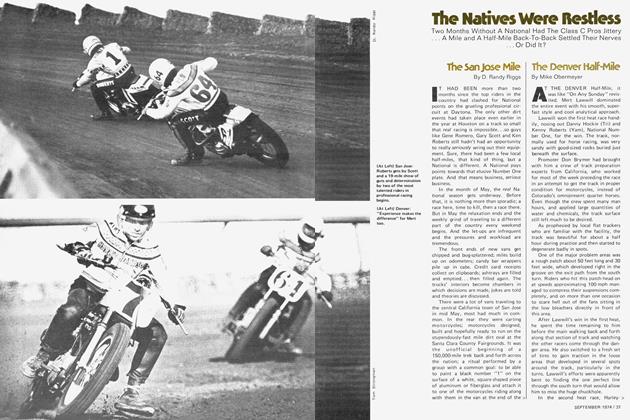

The Natives Were Restless

The Natives Were RestlessThe San Jose Mile

September 1974 By D. Randy Riggs -

The Natives Were Restless

The Natives Were RestlessThe Denver Half-Mile

September 1974 By Mike Obermeyer