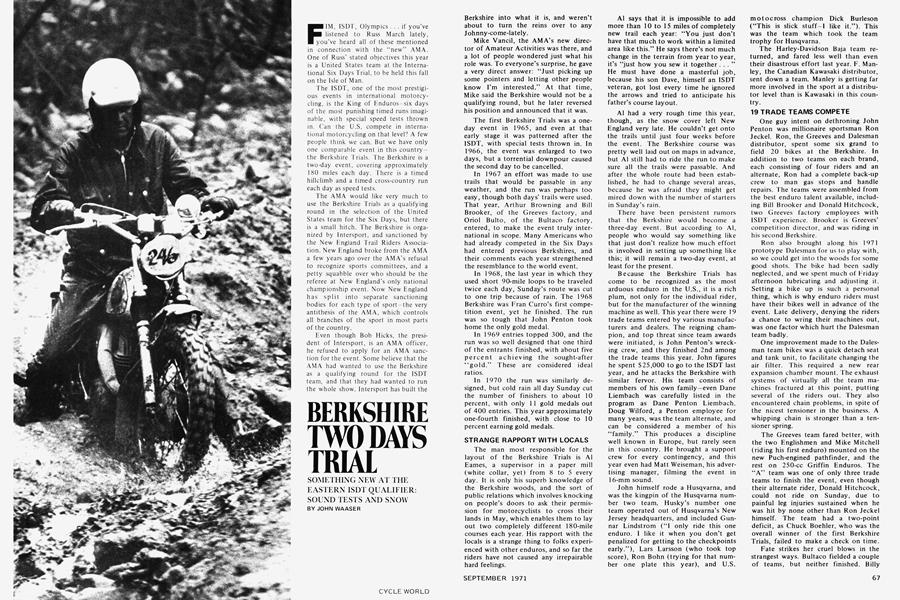

BERKSHIRE TWO DAYS TRIAL

SOMETHING NEW AT THE EASTERN ISDT QUALIFIER: SOUND TESTS AND SNOW

JOHN WAASER

FIM, ISDT, Olympics ... if you’ve listened to Russ March lately, you’ve heard all of these mentioned in connection with the “new” AMA. One of Russ’ stated objectives this year is a United States team at the International Six Days Trial, to be held this fall on the Isle of Man.

The ISDT, one of the most prestigious events in international motorcycling, is the King of Enduros-six days of the most punishing timed runs imaginable, with special speed tests thrown in. ('an the U.S. compete in international motorcycling on that level? A few people think we can. But we have only one comparable event in this countrythe Berkshire friais. The Berkshire is a two-day event, covering approximately 180 miles each day. There is a timed hillclimb and a timed cross-country run each day as speed tests.

The AMA would like very much to use the Berkshire Trials as a qualifying round in the selection of the United States team for the Six Days, but there is a small hitch. The Berkshire is organized by Intersport, and sanctioned by the New England frail Riders Association. New England broke from the AMA a few years ago over the AMA’s refusal to recognize sports committees, and a petty squabble over who should be the referee at New England’s only national championship event. Now New England has split into separate sanctioning bodies for each type of sport-the very antithesis of the AMA, which controls all branches of the sport in most parts of the country.

Even though Bob Hicks, the president of Intersport, is an AMA officer, he refused to apply for an AMA sanction for the event. Some believe that the AMA had wanted to use the Berkshire as a qualifying round for the ISDT team, and that they had wanted to run the whole show. Intersport has built the Berkshire into what it is, and weren’t about to turn the reins over to any Johnny-come-lately.

Mike Vancil, the AMA’s new director of Amateur Activities was there, and a lot of people wondered just what his role was. To everyone’s surprise, he gave a very direct answer: “Just picking up some pointers and letting other people know I’m interested.” At that time, Mike said the Berkshire would not be a qualifying round, but he later reversed his position and announced that it was.

The first Berkshire Trials was a oneday event in 1965, and even at that early stage it was patterned after the ISDT, with special tests thrown in. In 1966, the event was enlarged to two days, but a torrential downpour caused the second day to be cancelled.

In 1967 an effort was made to use trails that would be passable in any weather, and the run was perhaps too easy, though both days’ trails were used. That year, Arthur Browning and Bill Brooker, of the Greeves factory, and Oriol Bulto, of the Bultaco factory, entered, to make the event truly international in scope. Many Americans who had already competed in the Six Days had entered previous Berkshires, and their comments each year strengthened the resemblance to the world event.

In 1968, the last year in which they used short 90-mile loops to be traveled twice each day, Sunday’s route was cut to one trip because of rain. The 1968 Berkshire was Fran Curro’s first competition event, yet he finished. The run was so tough that John Penton took home the only gold medal.

In 1969 entries topped 300, and the run was so well designed that one third of the entrants finished, with about five percent achieving the sought-after “gold.” These are considered ideal ratios.

In 1970 the run was similarly designed, but cold rain all day Sunday cut the number of finishers to about 10 percent, with only 1 1 gold medals out of 400 entries. This year approximately one-fourth finished, with close to 10 percent earning gold medals.

STRANGE RAPPORT WITH LOCALS

The man most responsible for the layout of the Berkshire Trials is AÍ Eames, a supervisor in a paper mill (white collar, yet) from 8 to 5 every day. It is only his superb knowledge of the Berkshire woods, and the sort of public relations which involves knocking on people’s doors to ask their permission for motorcyclists to cross their lands in May, which enables them to lay out two completely different 180-mile courses each year. His rapport with the locals is a strange thing to folks experienced with other enduros, and so far the riders have not caused any irrepairable hard feelings.

AÍ says that it is impossible to add more than 10 to 15 miles of completely new trail each year: “You just don’t have that much to work within a limited area like this.” He says there’s not much change in the terrain from year to year, it’s “just how you sew it together...” He must have done a masterful job, because his son Dave, himself an ISDT veteran, got lost every time he ignored the arrows and tried to anticipate his father’s course layout.

AÍ had a very rough time this year, though, as the snow cover left New England very late. He couldn’t get onto the trails until just four weeks before the event. The Berkshire course was pretty well laid out on maps in advance, but AÍ still had to ride the run to make sure all the trails were passable. And after the whole route had been established, he had to change several areas, because he was afraid they might get mired down with the number of starters in Sunday’s rain.

There have been persistent rumors that the Berkshire would become a three-day event. But according to AÍ, people who would say something like that just don’t realize how much effort is involved in setting up something like this; it will remain a two-day event, at least for the present.

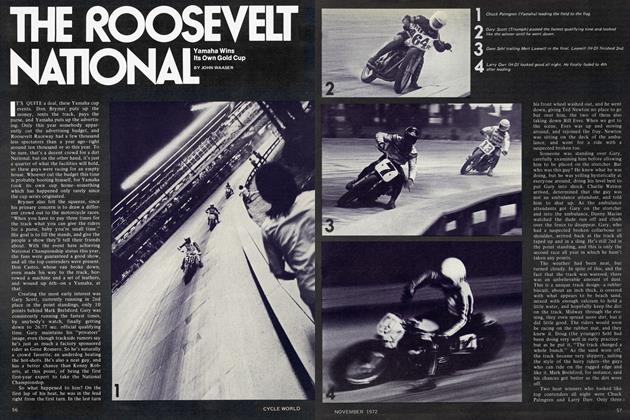

Because the Berkshire Trials has come to be recognized as the most arduous enduro in the U.S., it is a rich plum, not only for the individual rider, but for the manufacturer of the winning machine as well. This year there were 19 trade teams entered by various manufacturers and dealers. The reigning champion, and top threat since team awards were initiated, is John Penton’s wrecking crew, and they finished 2nd among the trade teams this year. John figures he spent $25,000 to go to the ISDT last year, and he attacks the Berkshire with similar fervor. His team consists of members of his own family-even Dane Liembach was carefully listed in the program as Dane Penton Liembach. Doug Wilford, a Penton employee for many years, was the team alternate, and can be considered a member of his “family.” This produces a discipline well known in Europe, but rarely seen in this country. He brought a support crew for every contingency, and this year even had Matt Weiseman, his advertising manager, filming the event in 1 6-mm sound.

John himself rode a Husqvarna, and was the kingpin of the Husqvarna number two team. Husky’s number one team operated out of Husqvarna’s New Jersey headquarters, and included Gunnar Lindstrom (“I only ride this one enduro. I like it when you don’t get penalized for getting to the checkpoints early.”), Lars Larsson (who took top score), Ron Bohn (trying for that number one plate this year), and U.S. motocross champion Dick Burleson (“This is slick stuff-I like it.”). This was the team which took the team trophy for Husqvarna.

The Harley-Davidson Baja team returned, and fared less well than even their disastrous effort last year. F. Manley, the Canadian Kawasaki distributor, sent down a team. Manley is getting far more involved in the sport at a distributor level than is Kawasaki in this country.

19 TRADE TEAMS COMPETE

One guy intent on dethroning John Penton was millionaire sportsman Ron Jeckel. Ron, the Greeves and Dalesman distributor, spent some six grand to field 20 bikes at the Berkshire. In addition to two teams on each brand, each consisting of four riders and an alternate, Ron had a complete back-up crew to man gas stops and handle repairs. The teams were assembled from the best enduro talent available, including Bill Brooker and Donald Hitchcock, two Greeves factory employees with ISDT experience. Brooker is Greeves’ competition director, and was riding in his second Berkshire.

Ron also brought along his 1971 prototype Dalesman for us to play with, so we could get into the woods for some good shots. The bike had been sadly neglected, and we spent much of Friday afternoon lubricating and adjusting it. Setting a bike up is such a personal thing, which is why enduro riders must have their bikes well in advance of the event. Late delivery, denying the riders a chance to wring their machines out, was one factor which hurt the Dalesman team badly.

One improvement made to the Dalesman team bikes was a quick detach seat and tank unit, to facilitate changing the air filter. 'Phis required a new rear expansion chamber mount. The exhaust systems of virtually all the team machines fractured at this point, putting several of the riders out. They also encountered chain problems, in spite of the nicest tensioner in the business. A whipping chain is stronger than a tensioner spring.

The Greeves team fared better, with the two Englishmen and Mike Mitchell (riding his first enduro) mounted on the new Puch-engined pathfinder, and the rest on 250-cc Griffin Enduros. The “A” team was one of only three trade teams to finish the event, even though their alternate rider, Donald Hitchcock, could not ride on Sunday, due to painful leg injuries sustained when he was hit by none other than Ron Jeckel himself. The team had a two-point deficit, as Chuck Boehler, who was the overall winner of the first Berkshire Trials, failed to make a check on time.

Fate strikes her cruel blows in the strangest ways. Bultaco fielded a couple of teams, but neither finished. Billy Dutcher lost a condenser for about the umpteenth time at this event. He still doesn’t carry a spare. One of the traveling course marshalls rode a Bultaco, and also had condenser trouble. They took an old Plymouth condenser, borrowed a puller, mounted the condenser externally, and wired it in. The bike started first kick, and never missed a beat.

Ossa had a team there also, which also failed to finish intact. Yankee Motors President John Taylor couldn’t find a 250 to ride anywhere, so the story goes, and borrowed his wife’s 175. Following his debut in the 1968 Berkshire Trials, Fran Curro became a hot motocross star. He had ridden a Bultaco in that first event, but John Taylor congratulated him anyway, and Fran switched to an Ossa. He injured his knee over a year ago, and stopped riding. His knee is now better, so he fitted his old Stiletto with lights and muffler, and rode it in this year’s event. He finished, though there wasn’t too much left of the bike at the end.

MOST PASS SOUND TEST EASILY

Many of the Husqvarna riders also used this technique of riding a motocross machine with rudimentary lighting systems and muffling. This may have been why so many Husky riders found themselves disqualified at the sound test. For the sound test, the “A” scale was used, which is the most sensitive to high-pitched sounds. Intersport had tried Radio Shack’s low-cost decibel meter, but discovered it was insensitive to high frequencies. It cuts off at about one kc, while the Scott and General Radio meters which they used go to 10 or 15 kc. intersport had set a limit of 90 decibels at 50 ft. We watched a Greeves rider go through. “'These guys really cooperate,” said the meter reader, “them and the guys who ride the Dalesmans. They reall zonk it on.” Most riders didn’t know how really easy the standard was, and so held the revs down.

Records were kept oí the make and year of all machines, with the sound level, and the results will be tabulated and published at a later date. For kicks, Frank DeGray, who was scheduled to ride the event, but had his woods bikes destroyed in a fire at his shop, took his BMW R75/5 through the test. They clocked it at 77db. Several enduro bikes were actually quieter. Our Dalesman prototype went through at 84db, and that machine was downright annoying to ride on pavement stretches where the revs were held constant. The little Hondas were the quietest bikes in general, about 72db, with one Ossa, a Canadian “Six Days” model, going in at 74db. New stock Ossa Pioneers registered about 76db, Pentons about 78db. The Greeves and Dalesman bikes, revved hard, showed about 82db. Yamahas varied according to model, from 78db to a high of about 86db.

The only bikes which flunked the test were Husqvarnas, with about a half-dozen of the Swedish bikes failing. Factory representative Gunnar Lindstrom says Husqvarna is working on the problem, but you need volume in the expansion chamber to obtain power, and they won’t go to twin ports due to weight and cost problems. So, the only way they can obtain power is by having less restriction; hence, more noise. Some of the noise comes from straight-cut gears, but the factory does not want to go to power-robbing helical gears. 'They’re working on a new 250-cc enduro machine, which will be quieter (and presumably have less power). One rider was heard to comment, “I don’t want to spend SI400 for a bike to come up here and have to sweat passing inspection.”

Also new this year were roving course marshalls, to check for any illegal assistance accepted by riders. Ron Jeckel was the instigator here, as he complained that last year one rider pulled a new bike off a truck and rode that out on the course while a new top end was put on his machine. He then got his own machine back in time to check in at the finish. Fach marshall had specific points at which he would enter the course with the early riders, and cruise slowly through, so as to arrive at the end of his section with the late riders. Frank DeGray put knobbies and a super fender on his R75/5, and became a course marshall. Took a lot of ribbing about it, too, since a Be Em recently took a gold medal in the 1SDT.

BERKSHIRE/ISDT COMPARISON

The question arises: “How does the Berkshire Trials compare with the International Six Days Trial?” Well, the international event is held in a different country each year, so the terrain varies accordingly. The Berkshire Trials runs constantly through the same area. Bill Brooker indicated that you are likely to find a lot more mud in the Six Days than in the Berkshire. Then there’s the sportsmanship thing. People over there are expected to cheat, and they just see how much they can get away with. Here people are aghast when they catch someone cheating. And the rider’s attitudes? Over there nobody just quits. If it is humanly possible to make the bike start, they’ll ride the next day. Here we had a half-dozen or so bikes which finished Saturday’s run, and would have been permitted to ride on Sunday, just left standing in the empty paddock after Sunday morning’s start.

The run is organized along 1SDT lines by Americans who have participated in the world event. The going here is a little bit easier, especially since the Berkshire includes more areas where you can relax while going down the road. This is because they know that the bulk of their 400 entrants are not Six Days material. In the Six Days, they throw the hard stuff at you continuously; that’s the major difference in the run itself. But perhaps we can sense an even bigger difference in the attitudes of the competitors. Here it’s still a larksomething to do on a spring weekendfor perhaps half the competitors. There it’s deadly serious work. We recall being told by one European entrant in the ’68 event that the area in the Berkshires is ideal for holding the ISDT, should it ever come to the United States, except for the total lack of accommodations for the several thousand people who take part in the event.

It was obvious that western riders were not familiar with mud, snow, or trees. Jack Penton gave us a very amusing pantomime of a California rider approaching a tree, which would have resulted in an instant slug in the mouth for Cute Jack had it been witnessed by one of the Baja Boys. Before the 20-mile mark, one California rider had been spotted by the side of the trail on a stretcher, while a teammate waited with him. And Dean Goldsmith got lost, dropped a chain, and walked into the woods to answer a call of nature, all before 30 miles out. John Penton may have had a point when he stated that the single best preparation for participation in the Berkshire was riding in Ohio Hare Scrambles. Take a long course, in the middle of winter, with snow, mud, fallen limbs and other obstacles, point everybody in the right direction, and let them go for two or three hours of continuous riding at top speed-the guy with the most laps is the winner. No wonder these Penton youngsters are so good.

RAIN, MUD BOG RIDERS DOWN

We asked a number of top riders on Saturday if the nice weather made the event any easier to ride. They all bravely replied that rain made no difference. Gunnar Lindstrom did say that since he wears glasses, rain caused him some fog problems, but that was it. Nice weather had been forecast for both days this year, and many riders didn’t even bring rain gear. Sure enough (if you don’t like New England weather, wait 10 minutes, it’ll change . . .), Saturday night it rained. In fact it poured. Mike Bisco and Dave Rothberg, spectating, were sleeping outside under the stars. Said Mike, “If it rains, we’re dead.” They weren’t seen at all on Sunday.

Following Sunday’s run we didn’t have to ask anybody if the rain made any difference. Even the top riders were complaining that the trails would have been easier if it hadn’t rained. What happens is that the cycle of hot days and cold nights which gets the maple sap flowing, also does things inside the ground. The constant thawing and refreezing makes the ground like a giant sponge, sometimes several feet deep. This isn’t bad for the first guy through, but by the time number 580 gets there, even on a good day, the mud underneath is churned up. When it rains, this sponge turns into a deep mud bath. Now when number 580 comes through, he may not make it.

Spectators gather and start pointing out the best spot to the riders. But then the concentration of riders in that particular spot just makes that spot worse. This happened at one spectator point on Saturday. One late rider got wise, and struck off in a different direction, and made it through okay, while those who stayed to the right, as suggested by the spectators, frequently got stuck.

Since the Berkshire Trials is more than just a competition event-it is a place to gather and meet other enthusiasts-camping has long been a major attraction, and movies are shown on Saturday night. People who were involved in motorcycling several years ago show up to either run, or work, or spectate, and it seems that it’s about the only time of the year we get to see some of them. And, too, like Gunnar Lindstrom, we only get to this one enduro a year, so it’s our only chance to meet the enduro regulars.

For the entrant who aspires to world competition, the Berkshire Trials offers a firm step along the way. For the guy who just wants that shoulder patch which reads “Veteran of the Berkshire Trials,” the event offers an interesting challenge and a measure of his ability. For we outsiders (Ernie Cassidy recently described motoring journalists as “Professional Camp Followers”), it offers the compleat weekend.

BERKSHIRE RESULTS

400 entered; approximately 300 finished the first day; 103 earned medals.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

SEPT 1971 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Technical, Etc.

Technical, Etc.Balancing the Mighty Multi

SEPT 1971 1971 By Gary Peters, Matt Coulson -

Features

FeaturesIt's A Steal

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joseph E. Bloggs