Racing Review

BARSTOW TO VEGAS

BOB SANFORD

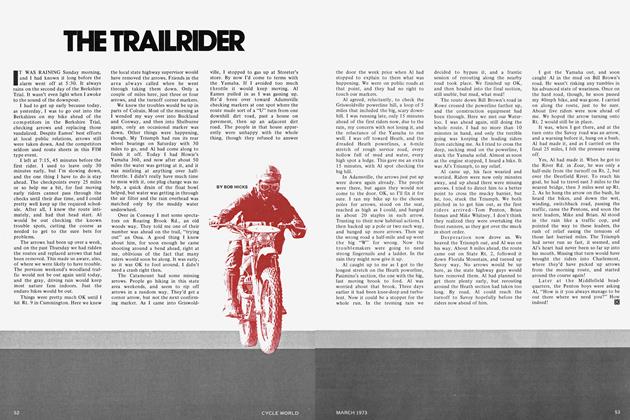

There are few things in motorcycle racing as spectacular as the start of the Barstow to Vegas Hare ’n Hound. Riders line up, side-by-side, in a slightly arching line that seems to extend for miles across the desert floor. Behind and at both ends of the line are thousands of people, as well as acres and acres of assorted campers, vans, trucks, cars and play bikes. Small, and some not so small, campfires dot the desert floor, while sharp, nippy, morning winds fan the fires and pop the hundreds of multi-colored banners which proclaim the worth of products and announce club affiliations.

On the starting line, riders are revving their engines and trying to stamp the cold from their heavily booted feet. Perhaps 200 yards in front of the line, a small group of people are doing something that apparently has the interest of everyone in the arching line. Suddenly, the small group raises a large banner and every engine and every rider becomes dead quiet, concentrating on the banner at their front.

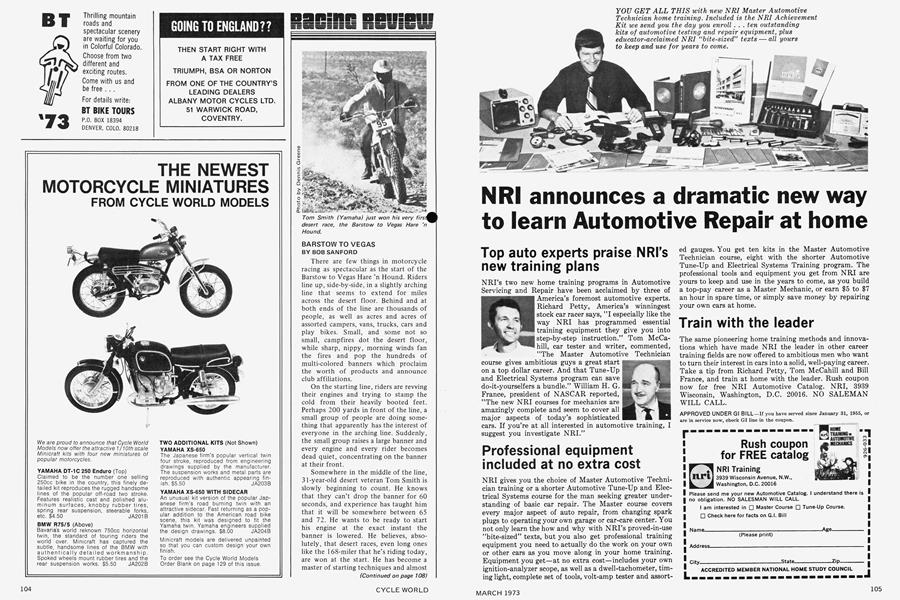

Somewhere in the middle of the line, 31-year-old desert veteran Tom Smith is slowly beginning to count. He knows that they can’t drop the banner for 60 seconds, and experience has taught him that it will be somewhere between 65 and 72. He wants to be ready to start his engine at the exact instant the banner is lowered. He believes, absolutely, that desert races, even long ones like the 168-miler that he’s riding today, are won at the start. He has become a master of starting techniques and almost always is in the top five to the smokebomb. One of his main advantages, he feels, is his Yamaha 360’s capacity for being started in gear. While other riders start their engines and fumble for 1st, he has already cleared the line and is smoothly shifting into 3rd.

(Continued on page 108)

Continued from page 104

As he counts, Smith thinks briefly of his serious competition. He knows who they are and where they are. Every one of them. Rolf Tibblin is a few riders to his left, Tom Brooks is just to his right, Gene Cannady is over there, A.C. Bakken left, Larry Pfutzenreuter right. Conspicious by his absence from the starting line is J.N. Roberts, the Hollywood stuntman and super-great desert rider.. Roberts, who had won the race the past four years, is still recovering from a non-racing injury.

At 67 seconds, the banner suddenly falls, and Smith slams his kickstarter, trying to bring life to his machine. First crank and he’s off, true to form, taking the lead.

Following Smith are nearly 1000 other Expert and Amateur riders, looking like little puffs of smoke madly dashing for the distant mother smoke, which signals the beginning of the actual course. The 1500+ Novices will follow in a few minutes.

Smith hits the bomb first and begins following the ribbon and stretching his lead over 2nd place Gene Cannady on a 3 5 0cc Honda. Somewhere near the front is 16-year-old Tom Brooks on a 125cc DKW. Brooks is a tiger of a rider and has taken the overall victory at more than one desert race this year. Besides, his 125cc, six-speed is faster than most 250s.

The course this year is easier and faster than in years past, but there are still plenty of obstacles to be dealt with. Sagebrush, ravines, rocks, uphills, sand, dust, downhills. Everything. Smith patiently follows his racing strategy by staying loose and going no faster than he can see. But his powerful Yamaha, with its top end advantage over even 400 Huskys, eats up the terrain, and he pulls into the first gas stop with a sizable lead over the still 2nd place man, Cannady. Leaving the pits, though, he is momentarily confused by the hundreds and hundreds of people in the area and loses his directions. He—literally—stops at a gas station, asks directions and proceeds down the course. But Cannady has narrowed the margin and is practically gobbling the dust from Smith’s rear knobby.

Twelve miles from the first gas, Cannady gets by, and Smith, as always, does not let the fact upset him or interfere with his concentration or rhythm. He knows he must keep Cannady in sight if he is to stand a chance, but he also knows that riding over his head is certain disaster. There is still plenty of time. Anything can happen.

Cannady does not stop to refuel at the alternate gas stop. Smith has planned a stop, hoping to avoid a repeat of last year’s disappointment, when he ran out of fuel between the alternate and the second gas stop. But he doesn’t want to lose sight of Cannady, so he takes the chance and continues the chase.

Twenty miles later, the Yamaha begins to sputter and slowly grinds to a halt. Out of gas. There is a camper nearby and Smith asks the people if they have any gas. Yes! He tops the tank, starts the engine and puts the bike> in gear...just as Tom Brooks approaches on his DKW. In a rare moment, Smith gasses too hard, slides out and lets Brooks by. (“It was a stupid thing for me to have done.”)

Coming into the second gas stop, the top three riders-Cannady, Brooks and Smith-are no more than 200 yards apart. After refueling, the three take off in the same order, but Smith errs for the second time that day and slides out, just as he’s leaving the pits. But he quickly recovers and the chase continues.

Some 15 minutes later, Smith zooms by Cannady, who has lost all but 2nd and 5th gears in his Honda. At Stateline, the final gas stop, Cannady, no longer in contention, calls it a day. But Smith is still very much in contention. He can no longer see Brooks, but at Stateline, he is told that, (A) Brooks has a 2-min. lead, and (B) Brooks has a 5-min. lead. Not that it matters that much to Tom Smith, because now he is confident of a win. He knows there is an awful lot of flat ground ahead and he feels his big Yamaha will simply outpower the little DKW.

But it’s not that simple. Smith does, in fact, finally catch sight of Brooks. But on a very long and very flat dry lake bed he quickly realizes that his big Yamaha is not much, if any, faster than Brooks’ DKW! The Yamaha does, however, prove to be sturdier, at least for this race.

Coming off the dry lake bed and with only 30 miles left to go, Brooks loses his header pipe, and thus much of his power. Smith shoots by and now it’s only a matter of keeping himself and his bike in one piece.

The Yamaha’s transmission, though, will no longer stay in 5th gear, so he must hold it in place with his boot to prevent it from jumping into 4th and destroying the engine. Blisters begin to form on the foot he is using to hold the gear change lever, but now there are just a few short miles to the finish line.

And there it is. Ahead, Smith sees a large group of people gathered around a solitary building, named, if you will, the Islander Bar. There have been thousands and thousands of people all along the course, but this is the group he’s been waiting to see. It’s been nearly four solid hours of riding, but Smith, like most desert veterans, takes the whole thing in stride. With his blistered foot, he downshifts carefully and picks his way past spectators and through the finisher’s chute, where he finally stops, accepts his magnum of champagne and the congratulations of scores of friends.

This has been one of the best days in Tom Smith’s life. He has raced the desert on nearly 150 occasions and this is his very first Hare ’n Hound win, although he has frequently and consistently been a bridesmaid. His racing strategy had finally paid off, and his machine, meticulously prepared by Yamaha of Glendale, has lived up to the capacity that he knew it had.

(Continued on page 112)

Continued from page 109

A dejected Tom Brooks limps through the finisher’s chute, followed shortly by A.C. Bakken and Rolf Tibblin on Husqvarnas. Larry Pfutzenreuter pulls in next on his Bultaco to take 5th overall and first 250.

Amazingly, by the end of the day, more than 1600 of the original 2500 riders will have finished the race. And each of the 1600 will feel more than a little proud, knowing that he or she has what it takes to finish the World’s longest Hare ’n Hound.

CASTROL SIX HOUR

ROBERT CROOKS

Over the last 20 years, Australia has produced some of the finest bike racers in the world. Some of them have gone over to Europe to try their luck and quite a few succeeded. But a lot of them have never left the country, and because we’re pretty much stuck at the end of the world, they have never become known on the world scene. Now, it looks as though that situation has changed. Last year, Agostini came out and got beaten. This year, more of the Europeans are coming out, and there is even a rumor that Cal Rayborn might like to come and try his hand.

The single event that has helped to focus foreign attention on the Australian scene more than any other has been the Castrol Six Hour Production race, which has been held annually at Amaroo Park near Sydney. Rushing any machine around this tight, 1.2-mile circuit for six hours provides the ultimate test of braking, handling and reliability.

This year’s event was a bonanza. The Yamaha factory put in a huge effort -through its local dealers by entering the new 750 Twins and the RD350s (with disc brake and six-speed box). To ride the big new four-strokes they employed nothing less than the best in the country—Ron Toombs, perennial race winner and ear ’oler extrodinaire; Bryan Hindle, who did the hatchet job on Ago last year; Bill Horsman, holder of the prestigious Duke of Edinburgh Award; and Tony Hatton, who has built himself a goodly reputation on local and interstate tracks.

Yamaha wasn’t the only one. The Benelli factory sent out its prototype six-cylinder 750. Unfortunately, it was still languishing in the hold of a ship at start time. MV entered a 750 Four, which effectively blew the collective mind of the crowd on race day. Kawasaki had one of its new 900s there, but elected not to race it. The Ducati 750s were racing, but they weren’t a new sight to the Australian crowds as they have been racing for some time there. And, of course, there was the inevitable flock of 750 Hondas and Kawasakis.

The show got going right on the dot of 10:00. After a mad scramble for bikes the field got away with Alan Hales (550 Suzuki) leading. Behind him were Craig Brown (750 Honda) and Brian Clarkson (MV Augusta). The rest of the herd of 70 riders were all in hot pursuit, all jammed together, and all looking as though they were about to participate in a momentous prang at any minute.

The Yamaha swarm was late away, with the quickest of them, Ron Toombs, lying in about 8th place. Toombs’ luck wasn’t to be holding on the day, and he dropped out after an hour and a half with a suspected main bearing seizure, after furiously dicing with Len Atlee (Norton 750 Interstate) for much of that period.

Teammate Bryan Hindle was to fare no better. He came into the pits after only a few laps with a mysterious misfire. The trouble was incurable and he eventually retired after two hour’s racing.

Things were going much more favorably for the other Japanese factories. Geoff Lucas (Kawasaki 750) had battled his way to the lead after two laps and started to put a goodly amount of empty track between him and the rest

Ipf the field. The rest of the field that is, except for Brown, who was not giving the big Three an inch. Lucas was well aware that he’d have to make ground early to make up for the giant thirst of his machine, which was eating up the juice at the rate of a tankful per hour. This meant that he was burdened with no less than five pit stops, twice as many as planned by his competitors.

(Continued on page 116)

Continued from page 113

By 10:30, the pace had settled down somewhat. Lucas still held the lead from Brown, with Tony Hatton (Yamaha 750) holding a comfortable 3rd. In the 500 class, early leader Brian Martin (Honda 500) had pulled into the pits with electrical worries, leaving Ross Hedley (500 Kawasaki) in the driver’s seat.

The big MV had a pit stop at 10:30 to fix a loose rear brake backing plate, but was soon back in it, half a lap down on its earlier position.

By 11:00 Lucas had pitted, fueled and rejoined the field, without losing h^^ lead. Level pegging Lucas for first place was...wait for it...a 315 Suzuki in the hands of Joe Eastmure.... Eastmure had been unobtrusively moving through the field since the start of the meeting, and when the 1 1:00 lap scores came through on the print-out not many people believed it. But there he was, and close behind him was Ross Hedley (500 Kawasaki), with Craig Brown scrambling to hold onto his 2nd place in the 750 class. But not for long. Within three-quarters of an hour, Brown had put his Honda’s chain through the gear-box and was involved in the long push back from the mountain.

Hatton’s Yamaha dropped out at 12:00 with an undiagnosed power loss.

The MV was out, too, with a failure of the drive train. Although it hadn’^^ been spectacularly placed, the noise tha^P it made when backing off for corners was something to be remembered.

Between 12:00 and 1:00, the first of the two Ducatis entered started to make its move. Rider Gordon Lawrence kept the wick turned up so that he moved from 5th to 2nd in the class within half an hour. The overall lead was now in the hands of Eastmure’s flying Suzuki, one lap ahead of his nearest competitor, Mike Steele, who had been fairly strategically placed since the start. Lawrence was less than a lap behind Steele, as was 3rd in class Bill Burnett (Honda 750).

In the 500 class, 2nd was still being held by Ross Hedley (Kawasaki 500) with the Crawford brothers (Kawasaki 500) a lap astern.

The highlight of the race after the midway mark was the battle bein^^ waged between Steele and Eastmurt^P The lead switched several times until at last Steele got it for good at 1:30, and began to put a substantial amount of track between him and the Suzuki.

For the last half hour, Steele and Eastmure were circulating side-by-side, although in actual fact they were separated by a full lap with Gordon Lawrence’s Ducati separating them. Eastmure was pressuring Steele severely, trying to force him into some sort of awkward situation. Five minutes from the end, Steele submitted to the strain.

They went up over the mountain and braked for Brabham-Ford loop, a notoriously difficult decreasing radius right hander with two apexes. Steele was pushed to the limit, and dropped his Kawasaki. Eastmure shot past him into what he thought was a comfortable 2nd place outright. But Steele wasn’t to be beaten. Within seconds of hitting the ground, he was back onto his feet and Jcicking his Kawasaki back into shape. rThe forks were bent, the mufflers broken, and the tank dented, but he got it going again, before Lawrence’s Ducati had a chance to go to the lead.

Steele hammered his tired old 750 around the last few laps and crossed the line at 4:00, with 333 laps completed.

The flag man didn’t realize that Steel and Lawrence had in fact completed more laps than Eastmure, and so flagged in the Suzuki as winner. Before anyone knew what was happening, the Television crowd had dragged Eastmure in front of the cameras and drowned him in champagne, crowning him victor of the 1972 Castrol 1000.

It wasn’t until several minutes later that everybody realized that a mistake had been made, and that Eastmure had only come 3rd (although even that wasn’t a bad effort considering the meagre capacity of his machine). The appropriate measures were taken, and the battered Mike Steele was pronounced winner, with Gordon Lawrence (Ducati 750) 2nd, and Joe Eastmure 3rd outright. There was more to come. All bikes are impounded after the meeting so that they can be stripped down, and checked to see that they are really standard.

This post-race scrutineering resulted in some startling revelations. Gordon Lawrence’s Ducati was disqualified. It certainly looked standard, but it seems there was a little matter of it having a capacity of 890cc.

As if this surprise enough, there then came the news that Joe Eastmure’s Suzuki was also disqualified. The reason? No horn.

It wasn’t until Monday that the results were finally cleared up. Steele won outright, with Max Robinson (Honda 750) 2nd and Ken Blake (Ducati 750) 3rd. 0