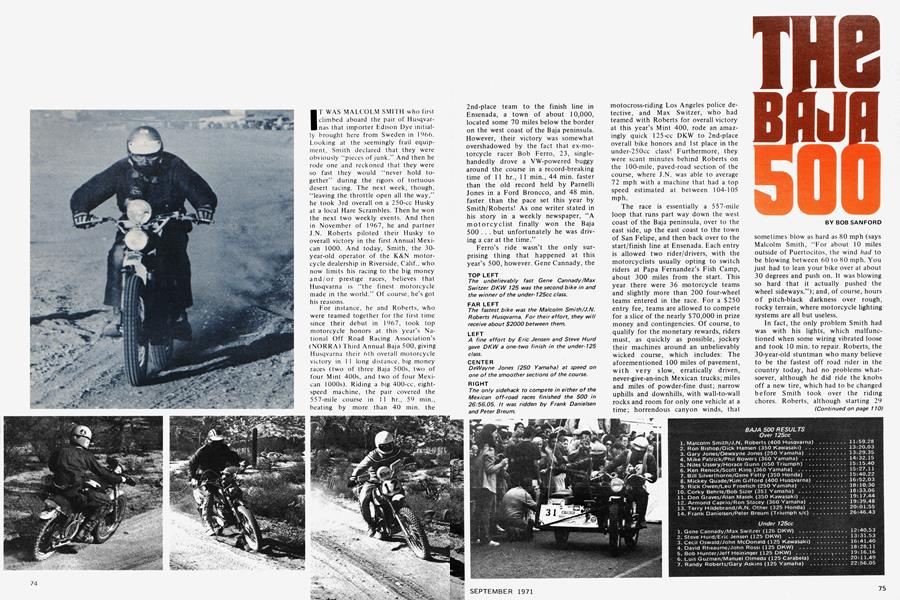

IT WAS MALCOLM SMITH who first climbed aboard the pair of Husqvarnas that importer Edison Dye initially brought here from Sweden in 1966. Looking at the seemingly frail equipment, Smith declared that they were obviously “pieces of junk.” And then he rode one and reckoned that they were so fast they would “never hold together” during the rigors of tortuous desert racing. The next week, though, “leaving the throttle open all the way,” he took 3rd overall on a 250-cc Husky at a local Hare Scrambles. Then he won the next two weekly events. And then in November of 1967, he and partner J.N. Roberts piloted their Husky to overall victory in the first Annual Mexican 1000. And today, Smith, the 30-year-old operator of the K&N motorcycle dealership in Riverside, Calif., who now limits his racing to the big money and/or prestige races, believes that Husqvarna is “the finest motorcycle made in the world.” Of course, he’s got his reasons.

For instance, he and Roberts, who were teamed together for the first time since their debut in 1967, took top motorcycle honors at this year’s National Off Road Racing Association’s (NORRA) Third Annual Baja 500, giving Husqvarna their 6th overall motorcycle victory in 1 1 long distance, big money races (two of three Baja 500s, two of four Mint 400s, and two of four Mexican 1000s). Riding a big 400-cc, eightspeed machine, the pair covered the 557-mile course in 1 1 hr., 59 min., beating by more than 40 min. the 2nd-place team to the finish line in Ensenada, a town of about 10,000, located some 70 miles below the border on the west coast of the Baja peninsula. However, their victory was somewhat overshadowed by the fact that ex-motorcycle racer Bob Ferro, 23, singlehandedly drove a VW-powered buggy around the course in a record-breaking time of 1 1 hr., 1 1 min., 44 min. faster than the old record held by Parnelli Jones in a Ford Bronceo, and 48 min. faster than the pace set this year by Smith/Roberts! As one writer stated in his story in a weekly newspaper, “A motorcyclist finally won the Baja 500 . . . but unfortunately he was driving a car at the time.”

THE BAJA 500

BOB SANFORD

Ferro’s ride wasn’t the only surprising thing that happened at this year’s 500, however. Gene Cannady, the motocross-riding Los Angeles police detective, and Max Switzer, who had teamed with Roberts for overall victory at this year’s Mint 400, rode an amazingly quick l25-cc DKW to 2nd-place overall bike honors and 1st place in the under-250cc class! Furthermore, they were scant minutes behind Roberts on the 100-mile, paved-road section of the course, where J.N. was able to average 72 mph with a machine that had a top speed estimated at between 104-105 mph. In fact, the only problem Smith had was with his lights, which malfunc tioned when some wiring vibrated loose and took 10 mm. to repair. Roberts, the 30-year-old stuntman who many believe to be the fastest off road rider in the country today, had no problems what soever, although he did ride the knobs off a new tire, which had to be changed before Smith took over the riding chores. Roberts, although starting 29 min. after the first bike left Ensenada, had managed to take over the lead by the third checkpoint in Santa Ynez, 238 miles from the start.

The race is essentially a 557-mile loop that runs part way down the west coast of the Baja peninsula, over to the east side, up the east coast to the town of San Felipe, and then back over to the start/finish line at Ensenada. Each entry is allowed two rider/drivers, with the motorcyclists usually opting to switch riders at Papa Fernandez’s Fish Camp, about 300 miles from the start. This year there were 36 motorcycle teams and slightly more than 200 four-wheel teams entered in the race. For a $250 entry fee, teams are allowed to compete for a slice of the nearly $70,000 in prize money and contingencies. Of course, to qualify for the monetary rewards, riders must, as quickly as possible, jockey their machines around an unbelievably wicked course, which includes: The aforementioned 100 miles of pavement, with very slow, erratically driven, never-give-an-inch Mexican trucks; miles and miles of powder-fine dust; narrow uphills and downhills, with wall-to-wall rocks and room for only one vehicle at a time; horrendous canyon winds, that sometimes blow as hard as 80 mph (says Malcolm Smith, “For about 10 miles outside of Puertocitos, the wind hud to be blowing between 60 to 80 mph. You just had to lean your bike over at about 30 degrees and push on. It was blowing so hard that it actually pushed the wheel sideways.”); and, of course, hours of pitch-black darkness over rough, rocky terrain, where motorcycle lighting systems are all but useless.

(Continued on page 110)

Continued from page 75

For their efforts, Smith and Roberts will receive about $2000 between them, which is really not all that much, considering the entry fee and the tremendous amount of time and money spent in preparing for and actually riding the race.

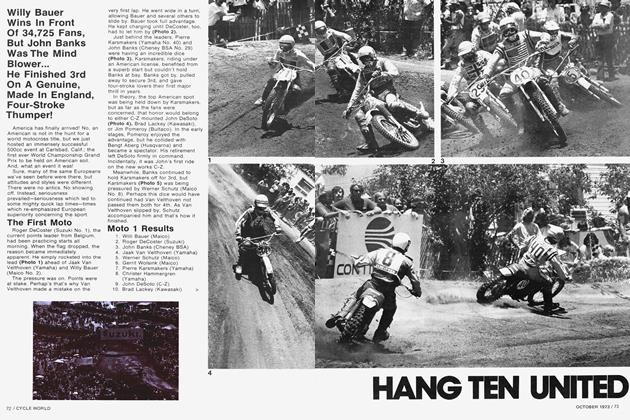

The race itself started at 12:01 p.m., with the 36 motorcycles leaving the starting line at one-minute intervals. Several thousand Mexican and American spectators were on hand to watch the starter greenflag the first bike-a 360-cc Kawasaki, ridden by Ron Bishop and Dick Hansen, the team that eventually ended up in 2nd place in big bore competition-down the starting ramp and toward the first checkpoint at Camalu, about 93 miles of pavement down the road. And finally, nearly five hours later, the last four-wheel vehicle was given the go-ahead. From then on, it was a matter of sitting around Ensenada, drinking Cerveza and following the race via NORRA’s radio communication with the nine checkpoints along the route. And at exactly 12:29.28 a.m., Malcolm Smith came barreling across the finish line, looking tremendously exhausted after his 230-mile ride. However, Bob Ferro reached the finish line at almost exactly 2 a.m., to take the overall victory on the basis of elapsed time.

Physical and mechanical attrition had, as always on these long distance races, taken its toll, with only 22 of the original 36 bike teams finishing the race within the 30-hr. limit. Included in the 22, however, was a Triumph sidehack, ridden by Frank Danielsen and Peter Breum, who completed the loop in 26 hr., 43 min. The same machine, incidentally, also completed last November’s Mexican 1000, and is the only such machine to ever enter, much less complete, either of these two races.

One of the unwritten goals for motorcyclists in these long distance events is to “beat those damn cars” for overall honors, a feat that last took place three years ago. It is not realistically likely to happen in the future, as the drivers get better, the equipment gets more sophisticated and the roads get smoother. Additionally, cars, with their massive lighting systems, have a clear advantage at night (“I know we could beat them,” said Smith, “if the race was run completely during daylight.”). But it won’t be. And cars will continue to take overall honors. Nuts! fñl

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

SEPT 1971 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Technical, Etc.

Technical, Etc.Balancing the Mighty Multi

SEPT 1971 1971 By Gary Peters, Matt Coulson -

Features

FeaturesIt's A Steal

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joseph E. Bloggs