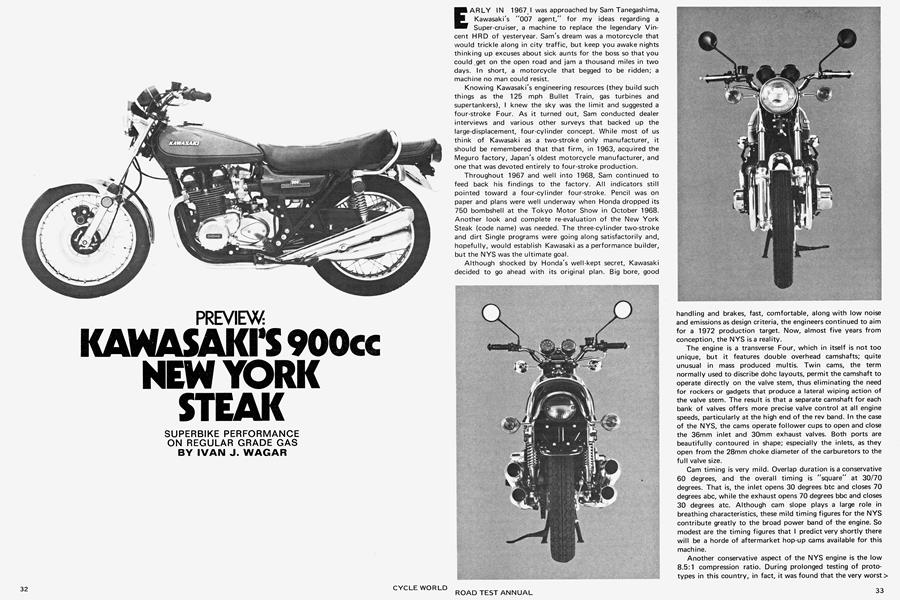

KAWASAKI'S900cc NEW YORK STEAK

PREVIEW

SUPERBIKE PERFORMANCE ON REGULAR GRADE GAS

IVAN J. WAGAR

EARLY IN 1967 I was approached by Sam Tanegashima, Kawasaki's "007 agent," for my ideas regarding a Super-cruiser, a machine to replace the legendary Vincent HRD of yesteryear. Sam's dream was a motorcycle that would trickle along in city traffic, but keep you awake nights thinking up excuses about sick aunts for the boss so that you could get on the open road and jam a thousand miles in two days. In short, a motorcycle that begged to be ridden; a machine no man could resist.

Knowing Kawasaki's engineering resources (they build such things as the 125 mph Bullet Train, gas turbines and supertankers), I knew the sky was the limit and suggested a four-stroke Four. As it turned out, Sam conducted dealer interviews and various other surveys that backed up the large-displacement, four-cylinder concept. While most of us think of Kawasaki as a two-stroke only manufacturer, it should be remembered that that firm, in 1963, acquired the Meguro factory, Japan's oldest motorcycle manufacturer, and one that was devoted entirely to four-stroke production.

Throughout 1967 and well into 1968, Sam continued to feed back his findings to the factory. All indicators still pointed toward a four-cylinder four-stroke. Pencil was on paper and plans were well underway when Honda dropped its 750 bombshell at the Tokyo Motor Show in October 1968. Another look and complete re-evaluation of the New York Steak (code name) was needed. The three-cylinder two-stroke and dirt Single programs were going along satisfactorily and, hopefully, would establish Kawasaki as a performance builder, but the NYS was the ultimate goal.

Although shocked by Honda's well-kept secret, Kawasaki decided to go ahead with its original plan. Big bore, good handling and brakes, fast, comfortable, along with low noise and emissions as design criteria, the engineers continued to aim for a 1972 production target. Now, almost five years from conception, the NYS isa reality.

The engine is a transverse Four, which in itself is not too unique, but it features double overhead camshafts; quite unusual in mass produced multis. Twin cams, the term normally used to discribe dohc layouts, permit the camshaft to operate directly on the valve stem, thus eliminating the need for rockers or gadgets that produce a lateral wiping action of the valve stem. The result is that a separate camshaft for each bank of valves offers more precise valve control at all engine speeds, particularly at the high end of the rev band. In the case of the NYS, the cams operate follower cups to open and close the 36mm inlet and 30mm exhaust valves. Both ports are beautifully contoured in shape; especially the inlets, as they open from the 28mm choke diameter of the carburetors to the full valve size.

Cam timing is very mild. Overlap duration is a conservative 60 degrees, and the overall timing is "square" at 30/70 degrees. That is, the inlet opens 30 degrees btc and closes 70 degrees abc, while the exhaust opens 70 degrees bbc and closes 30 degrees ate. Although cam slope plays a large role in breathing characteristics, these mild timing figures for the NYS contribute greatly to the broad power band of the engine. So modest are the timing figures that I predict very shortly there will be a horde of aftermarket hop-up cams available for this machine.

Another conservative aspect of the NYS engine is the low 8.5:1 compression ratio. During prolonged testing of prototypes in this country, in fact, it was found that the very worst grade of gasoline available would not produce pinging. For that reason the owner's manual will recommend regular grade gasoline. Due to the planned low compression and overall general mildness of the engine, Kawasaki engineers opted for a needle bearing crank.

Quite common in racing engines, both auto and motorcycle, roller bearing cranks are not often found where lugging-type loads are imposed on the engine. In those cases, usually a plain shell-type bearing is employed using a twopiece connecting rod. The free-revving characteristics of the big Kawasaki, however, permit the use of the lower friction (less heat) caged needle roller bearing. Also, through the use of needle bearings, connecting rod weight is kept to a minimum through the use of a one-piece unit.

The only other unusual feature about the pressed together 9-piece crank assembly is the power takeoff for the primary drive. In an effort to minimize drive train snatch, the engineers decided to cut gear teeth directly on the flange of the inside cheek of the number four crankshaft counterweight.The result is a very compact, direct primary drive system, which eliminates the need for idler gears or chains.

Drive for the two overhead camshafts is taken from the center of the crank. An endless, single-row chain, with an externally adjustable tensioner at the back of the cylinder block, serves to drive the cams. The engine oil pump is driven from a gear on the crank between the number one and number two cylinders.

The unique primary drive, the use of narrow one-piece rods, chain drive for the cams and, indeed, all crankshaft design criteria hinged on the shortest crank possible. And for a 900cc in-line unit, the NYS has a handsomely narrow engine. Similar to most car engine layouts, the crankpins are set as if a pair of 180-degree Twins were mated together. Firing is thus 1,2, 4, 3 with the dual-point coil ignition supplying a wasted spark on the exhaust stroke.

Mounted behind the crankshaft, on the left side, the ample electric starter drives directly to the crank. Therefore, it is not necessary to select neutral; pull in the clutch and hit the button. There is a kick starter for dead battery operation. Kick starting, because the clutch is a conventional clutch mounted unit, requires finding neutral in the normal manner. The five-speed box features the now almost standard shifting arrangement of one down and four up on the left side.

Gearbox shaft location in the horizontally-split cases is maintained by a ball bearing on the mainshaft at the ipput end. The counter (lay) shaft is thus located at the output, and both shafts feature needle bearings at the opposite ends. Shifting, both up and down, is so smooth that the clutch is almost an ornament. The direct drive from the crankshaft on the primary has dictated an internal top gear ratio of 1.2:1. This is a change from the normal (Japanese) practice of high overdrive ratios for top gear.

Power out of the transmission is controlled by an eightplate clutch that looks like it could serve duty on a Mack truck. On the outer cover below the clutch housing there isa sight glass to indicate engine oil level. Although the engine, technically, is of wet sump design, optimum oil level is well below the crankshaft and other operating components; thus the engine functions as a dry sump unit, but with the compactness of an integrated wet sump engine.

To appease the conservationists, because most motorcycle riders are conservationists, Kawasaki has fitted a positive crankcase ventilation system on the NYS. Valve seat material is a special sintered alloy to permit the use of lead-free gasolines. Push-pull throttle cables operate the four VM 28 Mikuni carburetors in much the same manner as the racing CR series Hondas. The feel at the twist grip is light and positive, without the tiring effects of heavy return springs. Testers claim that synchronization adjustments were not necessary during the sessions here and in Japan. A molded one-piece air intake tract connects the carburetors to an air chamber with a sealed corrugated paper air cleaner.

The frame to house the mighty 900cc engine is as sturdy and compact in appearance as the power unit itself. Constructed of varying diameters of mild steel tubing, the frame is of basic full double loop design. There is generous gusseting at both the swinging arm pivot and steering head locations to stiffen these critical areas. The frame looks strong. The wide front down tubes feature heavy front engine mounting points, and the engine actually becomes an additional frame member between the down tubes and the swinging arm area. Both the front and rear suspension are Japanese Kayaba units, but built to specifications established by Kawasaki's Mr. Hatta.

One of the few components that appears to be taken from an existing Kawasaki model, the front disc brake has the same proportions as the 750 H2. The rear is a traditional 8-in. drum with a width of 1.5 in., and is more than adequate for the big machine. A new Dunlop K87 mk 11, 4.00-18 tire is fitted at the rear, while the front has an all new K103 tire, featuring a new tread pattern. To assist high speed stability, Dunlop Japan has designed the new front tire with three center ribs. The remainder of the tire profile is similar to a conventional Dunlop front.

Seat height is comfortable for a large machine. The flatish engine profile permitted by the dohc layout has resulted in a surprisingly low overall machine height. Even with my smallish 5 ft. 8 in. stature, I had no trouble reaching the ground with both feet while at a standstill. Both seat width and padding are comfortable and did not prove irritating during my brief ride. In standard modern fashion, the seat hinges to the side to expose the electrics and a small map pouch in the plastic rear seat extension.

Servicing the big NYS might look like a big problem, but the engineers gave very serious thought to service throughout the program. Changipg the rear wheel, for instance, requires the removal of the left hand pair of exhaust pipes. Each pair of pipes, however, is a slip fit into the cylinder head, and loosening a single bolt at the rear permits the removal of the pipes as a unit. After removing the rear wheel spindle, the wheel can be pushed forward to lift the endless chain over the sprocket and the wheel then can be pulled out of the chassis.

The engine can be stripped down to the crankcases without removing the unit from the frame. Crankshaft or gear box repairs will, however, necessitate complete engine removal.

Several components are rubber (shock) mounted to prevent vibration reaching the rider. Such things as footpegs, fuel tank, headlight, speedo/tach unit, mufflers, molded plastic sidecovers, seat and turn signal flashers all mount in a manner that reduces, or isolates, vibration. Strangely, the bars are not rubber mounted. Nor was there anytime during the test that I felt they should be, so smooth is the whole unit.

Unfortunately, the riding portion of the preview did not permit a true evaluation of the machine. I was permitted to run as hard as I wanted on the short, straight line factory test strip at Akashi. But there was no opportunity to test handling whatsoever. In a straight line, the NYS feels great at all speeds, even beyond 100 mph. It is rock steady. Even under severe braking the machine is superb. The front brake requires considerable indiscretion in order to be locked-up, but hauls the bike down fast when handled even in a casual fashion.

Although the machine is big, it did not feel top heavy in the slow speed turn-around at the ends of the strip.

One area of concern is why Kawasaki chose a chain for the final drive. Some argue that if this really is a Super-cruiser it should have a shaft to transmit all those horses to the back wheel. Realizing that chain life will be a problem, and that longitudinal rotating shafts are not completely desirable (not to mention horsepower loses of two right angle drives), Kawasaki opted for a positive feed rear chain oiler. Output from the pump, mounted in the left side of the gearbox housing, is proportional to output shaft rotational speed, and in the order of 3cc per hour at normal highway speeds. A maximum output volume of 5cc per hour can be accommodated, but that is well beyond the 100 mph mark.

Subjecting the machine to the worst possible weather conditions during the U.S. portion of the test, it looks like about 3500 miles for a rear chain. The rear tire, according to their findings, is going to be in bad shape after 6000 miles and both of these points will be stressed (hopefully) in the owner's manual.

But chains and tires seem to be the price that has to be paid for the luxury of owning the new super bikes. A study conducted by one manufacturer of a super bike showed that the average owner used his machine only 5000 miles per year! So what's a chain once a year.

On the plus side, this machine will loaf along at all legal speeds in this country. It runs quietly. On the California Highway Patrol measurement standard the factory claims 83db A, which is well below any required limits. The NYS feels glued to the road in a straight line. Apparently Mr. Hatta and the frame engineers have the handling sorted out, because there is no steering damper, nor did the NYS ever feel like it needed one.

When the machine is available in this country, the CYCLE WORLD road test will give you the real scoop on handling. In the meantime, based on limited exposure, the thing is great.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue