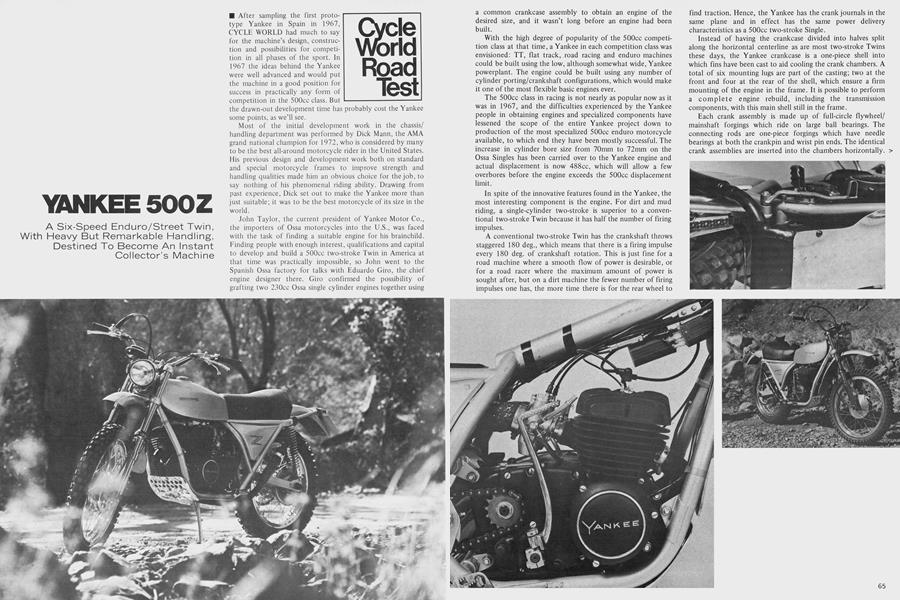

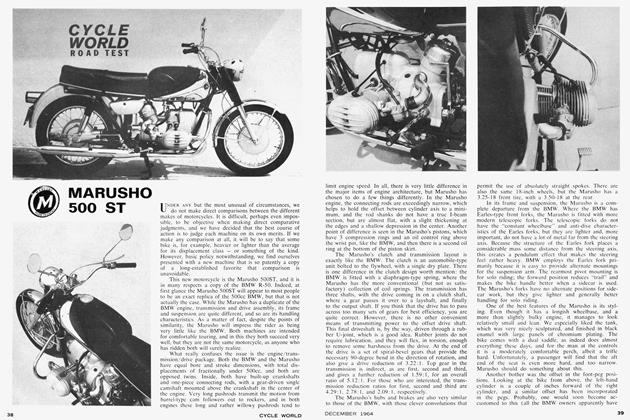

YANKEE 500Z

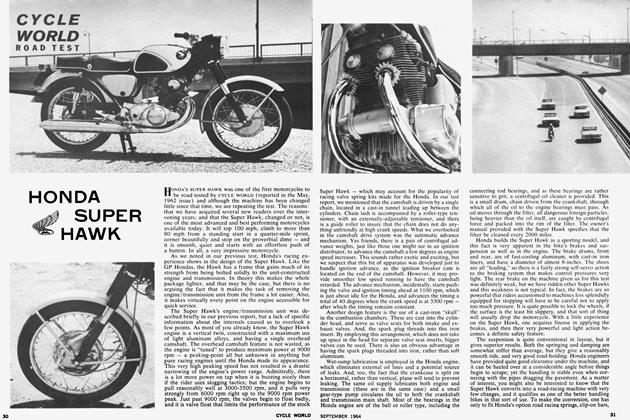

Cycle World Road Test

A Six-Speed Enduro/Street Twin, With Heavy But Remarkable Handling, Destined To Become An Instant Collector’s Machine

After sampling the first prototype Yankee in Spain in 1967, CYCLE WORLD had much to say for the machine’s design, construction and possibilities for competition in all phases of the sport. In 1967 the ideas behind the Yankee were well advanced and would put the machine in a good position for success in practically any form of competition in the 500cc class. But the drawn-out development time has probably cost the Yankee some points, as we’ll see.

Most of the initial development work in the chassis/ handling department was performed by Dick Mann, the AMA grand national champion for 1972, who is considered by many to be the best all-around motorcycle rider in the United States. His previous design and development work both on standard and special motorcycle frames to improve strength and handling qualities made him an obvious choice for the job, to say nothing of his phenomenal riding ability. Drawing from past experience, Dick set out to make the Yankee more than just suitable; it was to be the best motorcycle of its size in the world.

John Taylor, the current president of Yankee Motor Co., the importers of Ossa motorcycles into the U.S., was faced with the task of finding a suitable engine for his brainchild. Finding people with enough interest, qualifications and capital to develop and build a 500cc two-stroke Twin in America at that time was practically impossible, so John went to the Spanish Ossa factory for talks with Eduardo Giro, the chief engine designer there. Giro confirmed the possibility of grafting two 230cc Ossa single cylinder engines together using a common crankcase assembly to obtain an engine of the desired size, and it wasn’t long before an engine had been built.

With the high degree of popularity of the 500cc competition class at that time, a Yankee in each competition class was envisioned: TT, flat track, road racing and enduro machines could be built using the low, although somewhat wide, Yankee powerplant. The engine could be built using any number of cylinder porting/crankshaft configurations, which would make it one of the most flexible basic engines ever.

The 500cc class in racing is not nearly as popular now as it was in 1967, and the difficulties experienced by the Yankee people in obtaining engines and specialized components have lessened the scope of the entire Yankee project down to production of the most specialized 500cc enduro motorcycle available, to which end they have been mostly successful. The increase in cylinder bore size from 70mm to 72mm on the Ossa Singles has been carried over to the Yankee engine and actual displacement is now 488cc, which will allow a few overbores before the engine exceeds the 500cc displacement limit.

In spite of the innovative features found in the Yankee, the most interesting component is the engine. For dirt and mud riding, a single-cylinder two-stroke is superior to a conventional two-stroke Twin because it has half the number of firing impulses.

A conventional two-stroke Twin has the crankshaft throws staggered 180 deg., which means that there is a firing impulse every 180 deg. of crankshaft rotation. This is just fine for a road machine where a smooth flow of power is desirable, or for a road racer where the maximum amount of power is sought after, but on a dirt machine the fewer number of firing impulses one has, the more time there is for the rear wheel to find traction. Hence, the Yankee has the crank journals in the same plane and in effect has the same power delivery characteristics as a 500cc two-stroke Single.

Instead of having the crankcase divided into halves split along the horizontal centerline as are most two-stroke Twins these days, the Yankee crankcase is a one-piece shell into which fins have been cast to aid cooling the crank chambers. A total of six mounting lugs are part of the casting; two at the front and four at the rear of the shell, which ensure a firm mounting of the engine in the frame. It is possible to perform a complete engine rebuild, including the transmission components, with this main shell still in the frame.

Each crank assembly is made up of full-circle flywheel/ mainshaft forgings which ride on large ball bearings. The connecting rods are one-piece forgings which have needle bearings at both the crankpin and wrist pin ends. The identical crank assemblies are inserted into the chambers horizontally. >

The inner ends of the crankshafts fit into a four-row sprocket for a chain which transmits the power from the crankshaft to a jackshaft and then to the clutch. Taking the primary drive from the center of the engine instead of one side helps keep the overall width down to a reasonable level; very important on a large-capacity twin cylinder engine.

Because of the Yankee’s intended purpose, a 180-deg. crankshaft and wild cylinder porting are not needed. A smooth, progressive flow of power is obtained by using the same cylinders, small 24mm carburetors and low compression ratio of Ossa’s highly tractable Plonker, a trials bike. Yankees will be available on special order with a 180-deg. crank and different cylinders, but this setup isn’t for the faint of heart!

Twin exhaust header pipes curve downward and terminate in a muffler located between the underside of the engine and the sturdy aluminum skidplate. An outlet from the muffler curves gracefully upward on either side of the frame and terminates in a Krizman spark arrester. The exhaust system is designed and manufactured by Hooker Headers and obviously well suits the engine’s power characteristics besides effectively muffling the two-stroke crackle.

One of the best features of the engine besides the smooth, strong power delivery is the six-speed gearbox which was first used on Ossa’s powerful 250cc rotary-valve Single road racer. At the left end of the jackshaft is a 12-plate dry clutch which requires only a light pull on the lever to disengage. The straight cut gears on the end of the jackshaft and those on the clutch wheel add somewhat to the mechanical noise of the engine, but it is not objectionable, and all but disappears when the clutch is pulled in.

Having six closely-spaced gear ratios in an engine with a wide, flat torque band might seem superfluous, but in reality is a blessing. Low gear is so low that it is rarely needed except when picking one’s way through those “impossible” trials-type sections, and sixth is high enough to permit speeds in excess of 90 mph with comparative ease. For most general woods riding, second, third and fourth gears are used most often and the closeness of the ratios makes clutchless shifting a breeze without fear of tearing the gears out of the transmission. It’s really neat to have a gear for every corner one is likely to encounter where the engine can be kept revving exactly where the rider feels it to be providing the right amount of power.

The gearbox is easily modified to accept either a fiveor four-speed gearset if desired and was originally designed with that in mind because of the AMA’s former restriction of the gearbox to four speeds. In addition, the shifter shaft extends through to the right hand side so that the rider may convert to a right hand shift and left hand brake if he desires. Additional mounting lugs are provided for installation of the brake lever on the left side to simplify conversion.

Although it is hardly ever necessary, the clutch takes willingly to slipping and the gear lever travel is short with resultant crisp gear changes being the rule. We noted some sticking in the intermediate gears, probably due to the newness and tightness of the gearbox.

The heavy full-circle flywheels are aided by the weight of the external flywheels which surround Motoplat electronic ignition systems, one on each end of the crankshaft. This additional weight helps keep the engine pulling smoothly at low engine speeds where traction in mud or loose dirt is best. Once the ignition timing has been set, it shouldn’t be necessary to adjust it until the flywheel has to be removed. No contact points are used: ignition occurs as the flux density reaches a peak when the magnet passes over the stator coil. The resulting current is then fed to a transistorized circuit which triggers a silicon control rectifier located within the high voltage coil. >

YANKEE 500Z

$1495

Six-volt current is also provided by the Motoplat system to charge the battery and operate the lights and horn. The Yankee is fully street legal in every state so one can ride to his favorite field, go for a ride and then ride home again after it gets dark.

interested in combining the best components available into the Yankee, the rest of the motorcycle is a combination of Spanish and American bits. The front brake is identical to the one found on the Ossa Stilleto and Pioneer models and is a single leading shoe affair just slightly over 6 in. in diameter with a shoe width of 1.6 in. Even though it is an aluminum alloy casting and is fitted with an alloy rim, it is slightly heavy although very sturdy. It’s not too unusual, but the rear brake assembly certainly is. Using an alloy hub casting, steel brake disc and a healthy caliper unit all made in America, the rear disc brake provides truly phenomenal stopping ability, is unaffected by dirt and water and gives excellent “feel” at the brake pedal.

The line from the master cylinder to the caliper is steel-armored covered with rubber. At the other end of the hub the rear sprocket is isolated by rubber cushion blocks to ease the strain on the rear chain. Frendo “Competizione” linings are fitted to the front brake to reduce the possibility of fade, and the unit is well sealed to prevent the ingress of dirt and water. Strong, heavy spokes are used on both wheels.

Front suspension is accomplished by special forks made by Telesco with a healthy tube diameter of 1.65 in. Massive tripleclamps with a total of eight clamping screws are forged from 7075 T6 aluminum alloy by the Smith & Wesson firearms factory. Stainless steel handlebars and aluminum alloy control levers with finger tip cable adjusters complete the control group. Special hydraulic cushioning dampers in the forks prevent audible “topping out” when the front wheel is lofted. Tapered roller bearings are employed at the steering head. Rear suspension is admirably taken care of by special Telesco units designed especially for the Yankee. Slightly stiff initially, the units loosened up within 100 miles of off-road riding and feature five-way adjustable springs.

Very light oil is necessary in the front forks if they are to perform properly, and we didn’t feel that they were fully broken in. However, steering geometry is spot on for all but the slowest going and is very good for road riding at speed. No steering damper is fitted nor did we feel one was necessary. Sand washes and incredible whoop-de-dos could be negotiated with confidence at speed although the bike is quite heavy for really rough, picky going.

Massive, beautifully constructed and rugged enough to withstand a parachute drop are terms that best describe the frame and swinging arm. Largely the design work of Dick Mann, the double cradle unit features some of the largest tubes found on a motorcycle. Constructed of 4130 mild steel, the frame is quite conventional in design. A huge top tube of 2.5-in. diameter with a wall thickness of 0.049-in. terminates behind the gas tank. The front downtubes are 1.28-in. in diameter with a wall thickness of 0.065-in. These spread widely to accommodate the engine’s nearly 16-in. width, curve upward behind the transmission and terminate near the top rear shock mounting points. Two more tubes of the same size run rearward from the tail of the top backbone to the top shock mounting positions and a replaceable rear section, which supports the back portion of the rear fender, can be unbolted and changed in a matter of minutes if it is damaged.

Massive plates support the swinging arm pivot bolt and the swinging arm bearings are teflon-coated bronze with oil pockets to retain lubrication. Grease fittings are provided and are easily accessible. These bushings support a sturdy rectangular section swinging arm which measures 1.73 x 2.0 in. and undoubtedly contributes immensely to the machine’s rock steady handling qualities. Departing from normal practice, the bottom shock absorber mounting points are located behind the rear axle instead of in front.

The Yankee is built as a no-nonsense machine from the ground up and will be available from the dealer on special order in any number of different configurations. The basic package is truly a work of art. Some features that the experienced, as well as relatively inexperienced, rider will appreciate are the flexible plastic fenders that can be bent practically double before braking; the fiberglass side panels are attached with Dzus fasteners which can be removed easily for servicing the battery and voltage regulator. One thumbscrew is used to attach the seat which is removed to expose the toolkit and the aircleaner for easy servicing. The seat, incidentally, is very comfortable and provides good support for the rider’s backside without being too wide.

One thing that riders of smaller stature won’t appreciate very much is the sheer largeness and hefty weight of the motorcycle. The gas tank holds 3.25 U.S. gallons of gasoline which is enough for approximately 90 miles of serious trail riding, but it is quite wide and high off the ground. Add to that the width of the machine and you’ll find some disappointed short riders.

Much of the weight comes from the engine, which tips the scales at almost 90 lb., dry. Add to that the 32-lb. weight of the basic frame (less swinging arm), the enormous front suspension package, the wheels, the electrical system, and you have a machine weighing nearly 350 lb. ready to go. Much can be said in favor of heavier motorcycles with regard to comfort, but not in rough country unless the rider is in excellent physical shape and fairly hefty to begin with. Lifting the Yankee out of a mudhole or dragging it around a hillside can tire one out pretty quickly.

On the other hand, the entire package is so well thought out and constructed that it’s fairly hard to get into difficult situations. Almost 8-in. of ground clearance makes it easy to clear fallen logs and raises the wide engine high enough to go through narrow trenches without hanging up the crankcases. The engine is powerful and tractable enough to make it up almost any hill with decent traction, and the superlative suspension system is ideal for riders weighing 165 lb. and up.

The Yankee is disappointingly late in its arrival, but the finished package is worth the wait for the enthusiast.

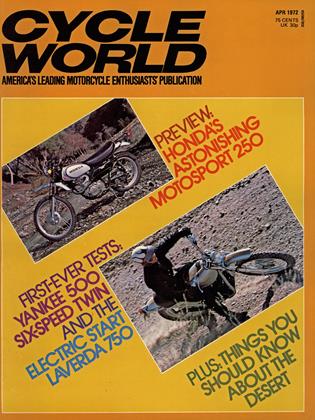

View Full Issue

View Full Issue