TECHNIQUE: THE FIREROAD

With Skip Van Leeuwen's Help, We Tell You How To Get More Fun Per Mile.

DAN HUNT

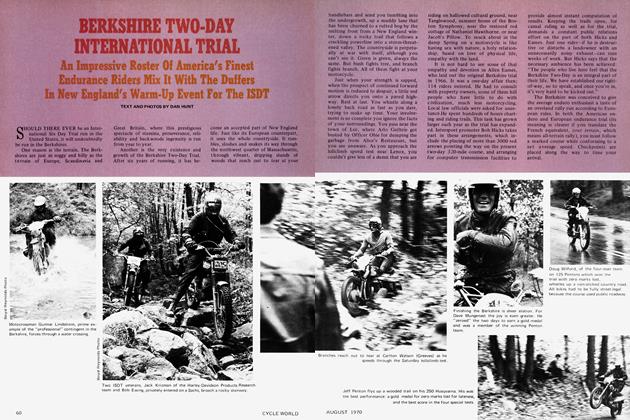

NOT MANY PROS I know would drive 150 miles to spend one hour running up and down a dirt road for no pay.

But Skip Van Leeuwen would. He's a fireroad freak.

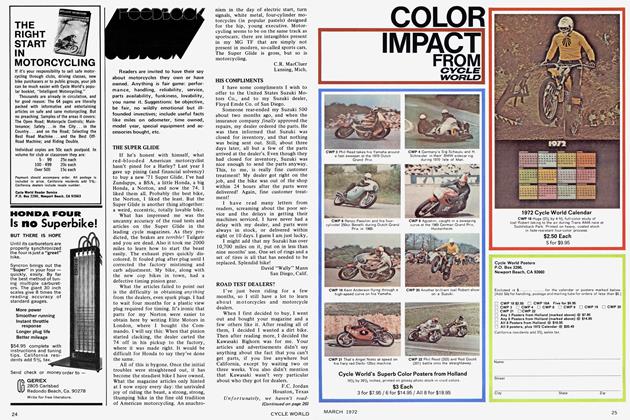

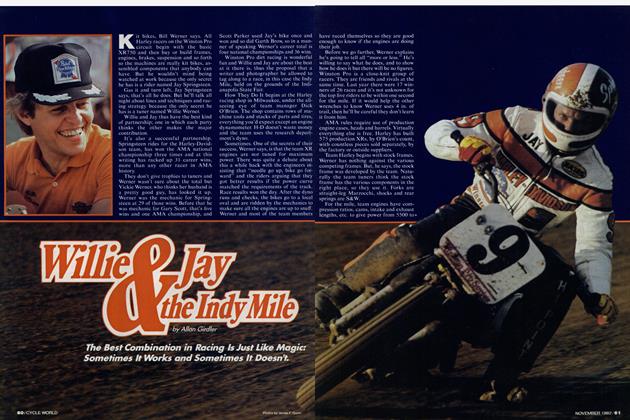

To make money, he races and wins AMA professional TT races, and promotes Buco helmets. He's won at the Astrodome. He's monopolized whole seasons at Ascot.

To relax, he likes to ride those curving, relatively smooth dirt roads in the country that we call fireroads. This kind of riding doesn’t have the jock aspect that motocross or enduro riding does. It’s mess-around riding.

It’s exciting because it’s fast and, when done right, involves a great deal of finesse. You slide and drift when running fast on a twisting mountain fireroad. The feeling is entrancing. You glide over the road in graceful swoops. Skiing parallel on the dirt.

Van Leeuwen was the ideal source for finding out how to fireroad better. A TT course is, in essence, a highly refined fireroad.

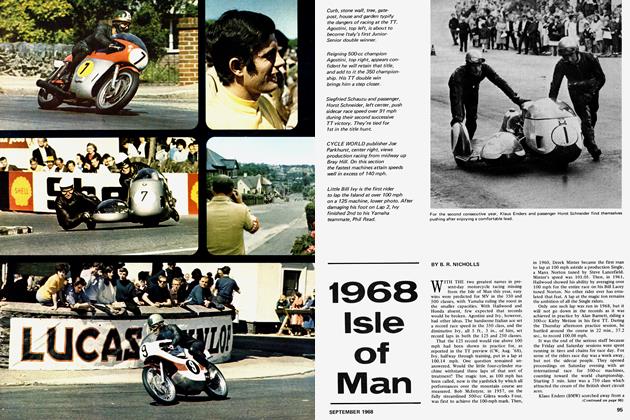

Rather than talk generalities, we picked a six-turn section of road at Saddleback Park. Skip’s task would be to run the road a few times and then analyze what he had been doing to get from Point A to Point B in the shortest time possible.

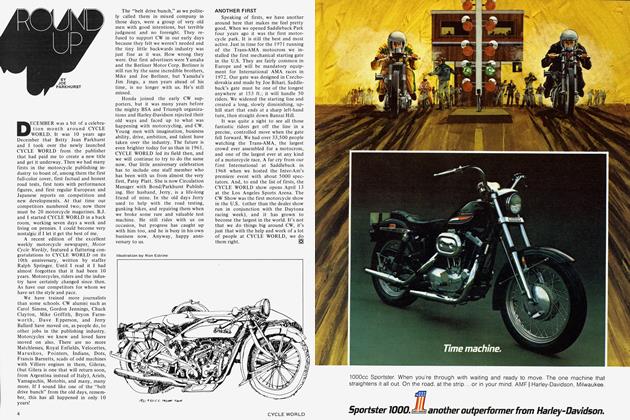

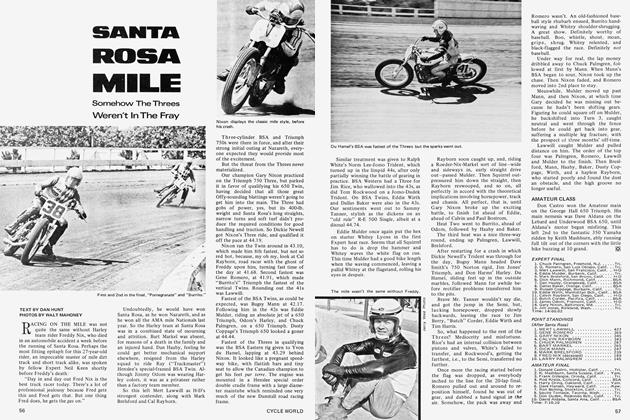

He didn’t use his own cowtrailer, a Triumph 650 which is set up specifically for sliding. Instead, he borrowed a 360-cc Bultaco Montadero machine from Bultaco Services’ rep Tom Patton. It was more like the bike an average guy would own, yet it had plenty of flexibility and torque for the job at hand.

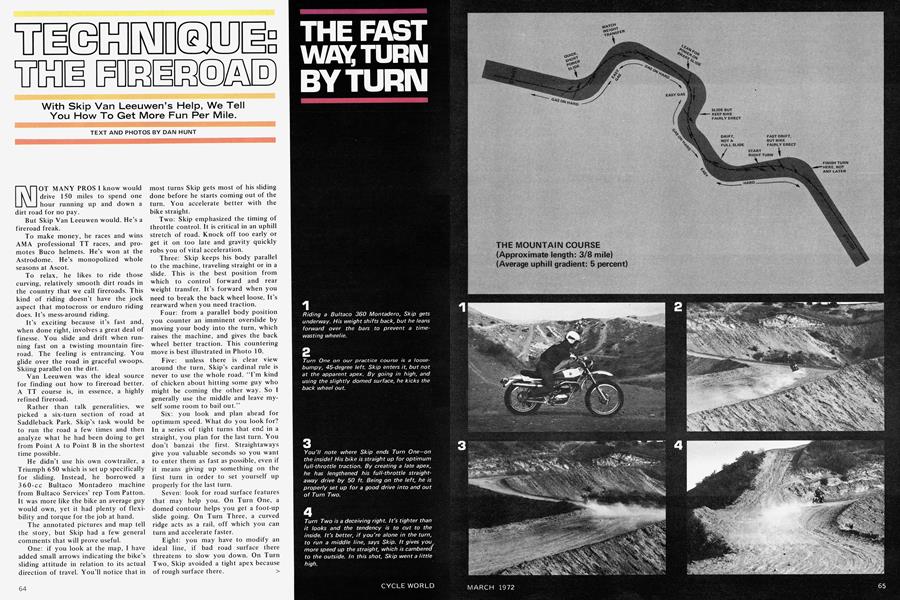

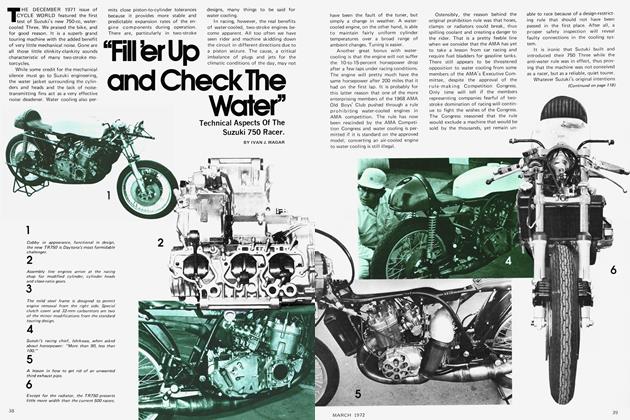

The annotated pictures and map tell the story, but Skip had a few general comments that will prove useful. One: if you look at the map, I have added small arrows indicating the bike’s sliding attitude in relation to its actual direction of travel. You’ll notice that in most turns Skip gets most of his sliding done before he starts coming out of the turn. You accelerate better with the bike straight.

Two: Skip emphasized the timing of throttle control. It is critical in an uphill stretch of road. Knock off too early or get it on too late and gravity quickly robs you of vital acceleration.

Three: Skip keeps his body parallel to the machine, traveling straight or in a slide. This is the best position from which to control forward and rear weight transfer. It’s forward when you

need to break the back wheel loose. It’s rearward when you need traction.

Four: from a parallel body position you counter an imminent overslide by moving your body into the turn, which raises the machine, and gives the back wheel better traction. This countering move is best illustrated in Photo 10.

Five: unless there is clear view

around the turn, Skip’s cardinal rule is never to use the whole road. “I’m kind of chicken about hitting some guy who might be coming the other way. So I generally use the middle and leave myself some room to bail out.”

Six: you look and plan ahead for optimum speed. What do you look for? In a series of tight turns that end in a straight, you plan for the last turn. You don’t banzai the first. Straightaways give you valuable seconds so you want to enter them as fast as possible, even if it means giving up something on the first turn in order to set yourself up properly for the last turn.

Seven: look for road surface features that may help you. On Turn One, a domed contour helps you get a foot-up slide going. On Turn Three, a curved ridge acts as a rail, off which you can turn and accelerate faster.

Eight: you may have to modify an ideal line, if bad road surface there threatens to slow you down. On Turn Two. Skip avoided a tight apex because of rough surface there.

THE FAST WAY, TURN BY TURN

RIGGING IT RIGHT FOR SMOOTH ROAD

YOU CAN FIREROAD just about /any competition or dual-purpose I I dirt machine sold today. Only some do it better than others.

Torque is advantageous. Half the fun is having an engine powerful enough to spin the rear wheel, at least in the low and intermediate gears. Thus, 175-cc or 250-cc engines would be as small as you’d want to go.

The traction you choose and the size of your wheels is important, too. Enduro bikes and motocross machines often have good enough geometry to be good sliders. But many of them are hampered by their as-sold riggingintended to give best performance over rough terrain.

NARROW TIRES SKATE

In most cases, a 2l-in. front wheel with a narrow motocross tire is a hindrance on a fireroad. It won’t stick when you “bury” the bike into a fast, smooth turn. The front wheel will tend to skate straight ahead.

This is why, for example, the Kawasaki 250E dual-purpose machine is a better fireroad machine as delivered than its nearly identical but bigger brother, the 350-cc Bighorn. The minor difference that makes the difference is that the 250 comes with a 3.25-19 Universal, while the 350 comes with a 3.00-21.

The same factor makes Honda’s latest SL350 a nice slider, and also helps the Yamaha and Suzuki Singles.

SWAP FOR A 19-INCHER

The Spanish 250s and 360s—Bultaco, Ossa and Montesa—all come with 21s. And they behave well enough that way. But the serious fireroader would benefit by swapping a 3.50-19 or 4.00-19 Universal for that 21-in. front.

Even a Husky or CZ motocrosser could be treated similarly. But, really, if all you were contemplating was fireroad work, you’d waste your money buying these specialized motocross machines in the first place.

One of the most fun dirt road bikes is the BSA Victor 500, either the MX or trail models. Four-stroke Single power produces beautifully controlled power slides. The Ducati 450 works fairly well but the seating position is high, making it better as a woods bike.

Sum ma cum laude on the fireroads goes to the Rickman-framed specials carrying Triumph 500 or 650 Twins, BSA 500 Single or Ducati 350 or 450 Single engines.

SELECT YOUR TRACTION

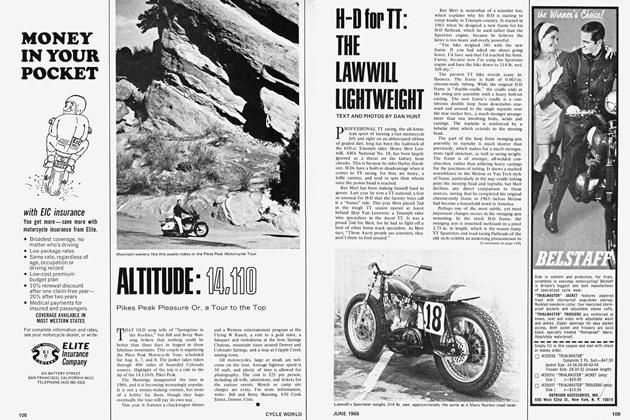

The right tire makes a startling difference between a good and indifferent fireroad machine.

We’ve already said that 21-in. fronts don’t make it. Neither do knobbies, front or back, which work only when there is enough cushion to grip.

If you plan to mix rough terrain riding with your fireroading, the blockpattern Dunlop Trials Universal is a good compromise. But it has one drawback—its flat profile. Get the bike laid over, hit a hard, slick surface and the blocks will distort suddenly. Off you go.

If you need a block pattern, but anticipate running on slick dirt roads, the Goodyear Grasshopper or the equivalent Firestone—a block pattern with rounded profile—is a better compromise.

If you are a hard-core fireroader and couldn’t give a hoot for running off into the boondocks, the Pirelli Universal or Dunlop K70 is the optimal choice. The Pirelli leaves some leeway for running on both soft and hard, smooth roads, while the K70 works better on dustcovered or slightly damp hardpan. The typical choice in size would be 4.00-18 or 4.00-19 rear, and 3.50-19 or 4.00-19 front, regardless of tread.

START FROM 24 PSI

Tire pressures are a personal thing, determined from experience. Start experimenting with approximately 24 psi front and rear. Use much less and the tire distorts too much when the bike is sliding.

Van Leeuwen would add that handlebars are important too. The bars on most dual purpose or motocross machines are either too straight or too high and forward.

You want a TT-style bar that is swept slightly backward and is designed to be used in the seated position. It must allow you to grip the throttle without having to bend your wrist. This minimizes hand and wrist fatigue. More important, it makes throttle control much more precise.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue