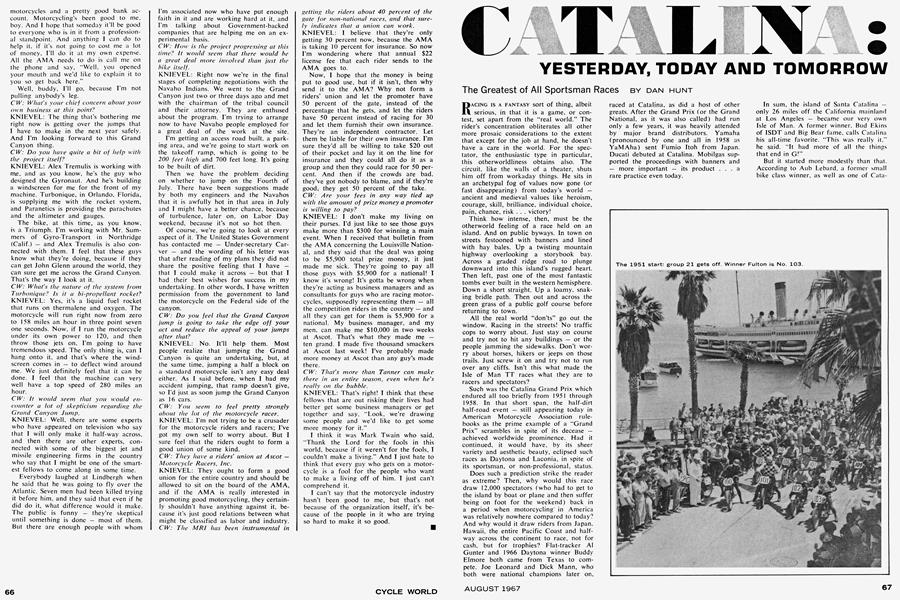

CATALINA: YESTERDAY, TODAY AND TOMORROW

The Greatest of All Sportsman Races

DAN HUNT

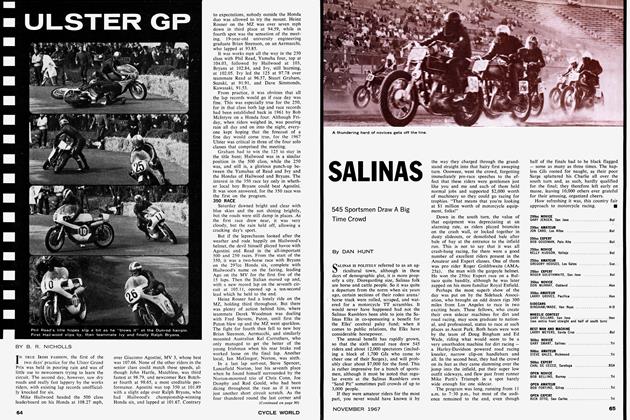

RACING IS A FANTASY sort of thing, albeit serious, in that it is a game, or contest, set apart from the "real world." The rider's concentration obliterates all other more prosaic considerations to the extent that except for the job at hand, he doesn't have a care in the world. For the spectator, the enthusiastic type in particular, this otherworldliness obtains also. The circuit, like the walls of a theater, shuts him off from workaday things. He sits in an archetypal fog of values now gone (or fast disappearing) from today's world — ancient and medieval values like heroism, courage, skill, brilliance, individual choice, pain, chance, risk . . . victory!

Think how intense, then, must be the otherworld feeling of a race held on an island. And on public byways. In town on streets festooned with banners and lined with hay bales. Up a twisting mountain highway overlooking a storybook bay. Across a graded ridge road to plunge downward into this island's rugged heart. Then left, past one of the most fantastic tombs ever built in the western hemisphere. Down a short straight. Up a loamy, snaking bridle path. Then out and across the green grass of a public golf course before returning to town.

All the real world "don'ts" go out the window. Racing in the streets! No traffic cops to worry about. Just stay on course and try not to hit any buildings — or the people jamming the sidewalks. Don't worry about horses, hikers or jeeps on those trails. Just screw it on and try not to run over any cliffs. Isn't this what made the Isle of Man TT races what they are to racers and spectators?

Such was the Catalina Grand Prix which endured all too briefly from 1951 through 1958. In that short span, the half-dirt half-road event — still appearing today in American Motorcycle Association rulebooks as the prime example of a "Grand Prix" scrambles in spite of its decease — achieved worldwide prominence. Had it continued, it would have, by its sheer variety and aesthetic beauty, eclipsed such races as Daytona and Laconia, in spite of its sportsman, or non-professional, status.

Does such a prediction strike the reader as extreme? Then, why would this race draw 12,000 spectators (who had to get to the island by boat or plane and then suffer being on foot for the weekend) back in a period when motorcycling' in America was relatively nowhere compared to today? And why would it draw riders from Japan. Hawaii, the entire Pacific Coast and halfway across the continent to race, not for cash, but for trophies? Flat-tracker AÍ Gunter and 1966 Daytona winner Buddy Elmore both came from Texas to compete. Joe Leonard and Dick Mann, who both were national champions later on. raced at Catalina, as did a host of other greats. After the Grand Prix (or the Grand National, as it was also called) had run only a few years, it was heavily attended by major brand distributors. Yamaha (pronounced by one and all in 1958 as YaMAha) sent Fumio Itoh from Japan. Ducati debuted at Catalina. Mobilgas supported the proceedings with banners and — more important — its product ... a rare practice even today.

In sum, the island of Santa Catalina — only 26 miles off the California mainland at Los Angeles — became our very own Isle of Man. A former winner. Bud Ekins of ISDT and Big Bear fame, calls Catalina his all-time favorite. "This was really it." he said. "It had more of all the things that end in G!"

But it started more modestly than that. According to Aub Lebard. a former small bike class winner, as well as one of Catalina's original organizers, the Southern California sportsman riders district (37) was merely casting about for an out of the way place to race. Catalina was the best of several candidates for a race where the type of crowd attending could be easily controlled while still allowing racing over a circuit of generous proportion.

"District 37 wanted a 'thingy' where only the enthusiasts would come." Lebard said, recalling trouble from "outsiders" and Angel types at the Hollister and Riverside tracks.

So Lebard, Frank Cooper and other reps sought support from the many factions that make up Avalon — sole town on the island of Catalina. Ultimately, however, the approval of the Wrigley family (of chewing gum fame) was sought and gained, for they were owners of the entire island, of which Avalon is only a one-square-mile piece. The fact that a P. K. Wrigley was a motorcycle fancier himself probably had much to do with the district's success.

A NEW SORT OF RACE

What kind of race was Catalina? To properly explain this, it should be noted that Catalina is a very rugged, young island — about 22 miles long by 10 wide — cross hatched by steep scrub-covered ridges jutting upwards from sea and canyon level to 1,500 and 2.000 foot height. It is only natural that, when the fellows from District 37 pondered this gorgeous bit of geological phenomenon, they started hankering for a rough country event — a hare scrambles to end all hare scrambles. The in-town sections would merely be frosting on the cake.

These dreams were quickly laid to rest by the Wrigley group which controls island affairs, the Catalina Island Company. An overly long rough scrambles event posed too many difficulties. There had to be compromises made. The end result was a 10-mile loop — three-fourths fireroad and one-fourth pavement. It could hardly be called rough scrambles.

But as committeemen Aub Lebard, Del Kuhn, Swede Belin, Frank Cooper, Howard Angel, Wes Drennan, and AMA official Harry Pelton tried out the course, they decided that maybe the compromise wasn't such a bad thing. Rather than raw ground, it was mostly cut and graded trail and road. As such, it allowed the use of Class C traction (universal tread patterns), rather than knobby tires, which would have been dangerous on the paved in-town sections. Ten laps of this course would be 10 scurrying laps, requiring finesse and good sliding style as well as stamina. (For the smaller machines, 250cc and under, a shorter four-mile loop was worked out using parts of the big bike course near town.) The course was twisty and there were only one or two straights in that 10 miles where a rider could exceed - briefly - 80 mph. Due to the nature of the land, the turns were tight and more likely to be right angles or hairpins than not. Except for the paved road, the dirt sections were quite narrow, just allowing the comfortable passage of a jeep ... or the very uncomfortable passage of two snarling motorcycles abreast.

And so was invented a new style of AMA dirt racing — the grand prix scrambles. It was fireroading, pure and simple. The style was peculiarly appropriate to western soil and terrain, and later was emulated in such events as the Corriganville and Tecate Grand Prix. The western predilection for the smooth, slidy, footdown specialty known as TT" scrambles probably owes as much to the popularity of Catalina as to anything else. (As sneering at anything less than a spine busting rough scrambles seems to be coming into vogue these days, it should be noted that smooth dirt events have a very strong and long heritage, not only in this country but abroad, in such offshoots as flat track, speedway, beach racing and grass track.)

The Catalina GP had a very "special" set of rules. In the big bore classes which raced on Sunday, competition was purely on an inch-for-inch basis, with only two classes - 350cc and open — although a 500cc class was added in 1958. Thus, an H-D 74 could run with a Triumph 30 or 40-incher. Strange? Not really, as Catalina had too many turns and too little straightaway in between to favor horsepower. Those who lay out TT scrambles courses could well use Catalina as a lesson: put some more turns in and put the race back in the rider's hands — instead of the tuner's.

An interesting sidelight: the big bore class gave no special consideration to engine design, and thus allowed even the overhead cam Nortons to run, as long as they were production machines.

In the smaller classes running on Saturday, sidevalves and two-strokes were given a displacement edge over the ohv machines to make up for their "obsolescence." This distinction was dropped in 1956, so that all classes were running inch-for-inch.

Catalina has often been paired off with the Isle of Man. Actually, it was probably more "Isle of Man" than the present race is overseas, for the Isle of Man originally was run on dirt roads.

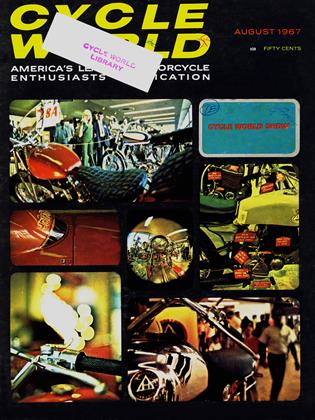

The Catalina entry was limited to 200 riders on Sunday and about 160 on Saturday, and in IOM fashion the big bores were sent off in waves — five every 30 seconds. The winner was judged on corrected time.

Catalina even had its own version of the parc ferme, where bikes — shipped over on the Catalina barge — were impounded until race time, and inspection. As an added fillip for the racers' friends, families and spectators, a beauty contest for the best looking machine and best turned out rider was held before the race. This explains the immaculate condition of most of the machinery. Beautiful paintwork, spotless plating, professional lettering, immaculate jersies were de rigueur. The polish was incredible for a sportsman event — something the viewer would sooner expect to see at a gala flat track meet at Ascot or Springfield.

CATALINA'S MEN AND MACHINES

The men who raced Catalina were a diverse bunch, as were the machines they rode. Catalina had to be an exciting thing — the stories of the also-rans are as fascinating as those of the winners.

Take Walt Fulton, for instance. He won the very first GP overall on a blatting Trophy Bird with megaphones, having surged past 51 riders in the very first lap. The megaphones, he admits, were as much for psychological effect as for speed: "When I came up behind a rider, he knew he was being followed, and most of the time would move over and let me by. I remember I used to yell a lot at a rider ahead of me. I was hoarse by the end of the race."

Curiously, Fulton - now a top-ranking executive with U.S. Suzuki — will better be remembered for the races he lost on that amazing small-wheeled American motorcycle called the Mustang. Twentieth the first year in the 250 sidevalve class, DNF in 1952 and fourth the third year, he went like the blazes while the diminutive machine kept running.

Fulton feels that the Mustang was one of the first machines to put it home to the American rider that good handling was far preferable to a few extra horsepower. For some strange reason, the funny looking Mustang had handling in spades which made up for a weakish engine and gearbox. Funny looking? You bet. They laughed at Walt when he showed up at his first race on one, but they didn't laugh long.

At the other end of the scale was Ray Tanner and his 74-cubic-inch HarleyDavidson. There is little doubt that he was the object of some ridicule as he rode this brutish anvil around those winding 10 miles, but nobody can argue with the results - 6th overall in 1951, 4th in 1952, 7th the next year and in 1956, and 6th in 1958.

Everyone got giggles of a different sort from Fumio Itoh — the Yamaha factory rider sent from Japan to contest the GP in 1958. Later to distinguish himself internationally as a Grand Prix road racer, he hairily demonstrated his skill on the paved sections of the Island course. While his fireroad style wasn't on a par with his road style, and he thus spent a significant part of the race using his back for a skid instead of his foot, he still managed a very respectable 6th place, only 38 seconds behind another Catalina rider who went on to great things, NSU-mounted David Ekins.

The variety of brand names in the bigbore winner's circle was as monotonous as it now is in AMA racing. Triumph with Fulton in 1951, Bud Ekins in 1955, and double winner Bob Sandgren in 1957 and 1958. BSA won it twice with Nick Nicholson in 1952 and Chuck "Feets" Minert in 1956. In fact, that year BSA won all three classes entered, with CYCLE WORLD'S Advertising Manager, Jerry Ballard, winning the 350 category. Velocette, a bike not often heard of these days in American racing but quite formidable then, won Catalina overall twice — in 1953 with road racer John McLaughlin riding and again the next year with Jim Johnson.

(Continued on page 88)

Harley-Davidson mounted a formidable attack on the Catalina crown in 1953 with two "K" models ridden by Charles Cripps and the fantastic Joe Leonard. But they were relegated to second and third place by John McLaughlin, who won overall on a brand-new Velocette displacing only 350cc! McLaughlin had a curious approach to Catalina, setting up his machinery with rather radical cam timing, to the point where he often had to slip the clutch coming out of corners, to get on the bottom of the power band at about 4,000 rpm. Through town, his road racing talent showed up well in a clean, foot-up style through the bends. He also won the 250 class that year on a Velo with an even rattier cam that came in above 5,000 rpm!

Bud Ekins, the 1955 winner, holds the distinction of setting the fastest all-time race record at Catalina (100 miles in 3 hours, 8 minutes and 49.99 seconds), which is no surprise as he was hitting his peak as a rider then and used to wow them on the Big Bear run by outrunning the pace plane when he hit open desert.

Bud, who has competed and won in European motocross, the ISDT, and all the big desert events, would gladly toss all those victories away for the one at Catalina, if he had the choice of only one win in a lifetime. "The Big Bear run may have been more grueling," he says, "but I practiced more for Catalina. Some races I might prepare for by riding for a few days to get in shape, but for Catalina, I'd ride the fire roads in the Hollywood Hills every day for a week."

His Catalina race record resulted partly from confusion in his pits. He had already built up a comfortable lead early in the race, but his pits misinformed him that he was being pressed: "They told me to go ... so I went."

Nick Nicholson, the Greeves distributor who has campaigned both here and abroad in famous dirt and road racing events, probably holds the most consistent record at Catalina with 10 finishes out of 10 starts, and five first places, including, of course, his big-bore win in 1952.

Many of the bikes extant then and entered in the race are no longer commonplace: Mustang, Rudge, Excelsior, James, Francis-Barnett, Puch, Ceccato, MV, Horex, Taurus, NSU, DKW, AJS, and Ariel. Some have since made, or are now making strong comebacks: Zundapp, Maico, Jawa, Moto-Guzzi, and even Guazzoni. WHY CATALINA DIED

Perhaps one of the worst wounds sportsman motorcycle competition ever inflicted upon itself was allowing Catalina to die without a full explanation to the public. After it was learned that there would be no Catalina GP in 1959 or ever again, the rumors going around were atrocious. It was either "the Hells Angels busted it up," or, "somebody molested the mayor's daughter," or, "they busted up the town." These rumors, of course, were vicious and untrue, but as is the case with all unfounded rumor, nobody stepped forward with the proper answer, loud and clear.

(Continued on page 90)

No single thing or incident killed Catalina. It was a combination of many things: a change of power in the factions that govern the small town of Avalon: an annoyed Catalina Island Co. staff faced with extra work each May; perhaps a bit of fatigue on the part of District 37; the general bad image cast upon motorcycling during that post-war period; an offended group of older retired people in Avalon found little beauty in those swift noisemakers which flashed through town, occasionally scattering hay and laying down a patina of rubber at every broadsliding turn.

Truth of the matter is that there were less incidents of a destructive or menacing nature from the motorcycle enthusiasts who thronged, regularly as clockwork, to the island each year, than there were from a notorious group of insurance salesmen who convened there, or from the "yachtsmen" who attended Buccaneer Days, an event designed to replace the Catalina GP in the somewhat tenuous Avalon tourist economy. The irony is that the motorcyclists, being landlocked creatures, spent more money in Avalon than boatmen have ever spent in the same time period.

Will there ever be racing on Catalina again? It may come as a shocker, but there is now. The Islanders MC, a Catalina motorcycle club, has little club meets on a small (relatively speaking) TT scrambles course just off the Avalon golf course. The natives can go there to practice any time they feel like it.

A race like the old Catalina? Perhaps never. But other areas of Catalina, yes. Aub Lebard, Norm Lee and others have approached island groups in recent years. "We could have a race there right now. if we'd throw it out of town, up behind the airport," Lebard says. "But the restrictions Wrigley gave us are ridiculous. Fifty bikes and only 1,500 spectators. Let's face it. The old Catalina was great because it went through town. People could watch the race and have the conveniences of town nearby."

This is a good point, and there are many who agree with it in District 37. However, the island of Catalina has more than one possible course of interest to riders, if not spectators. A complete 2Vimile loop, half paved road, exists near the rock quarry, far enough out ot town to remove the noise factor without makine it overly difficult for spectators to reach the course by foot or shuttle. Inland towards the isthmus, there exists a potential road racing course of Isle of Man caliber more than 20 miles long, not to mention magnificent scrambles country.

But, it all belongs to the Wrigley family, and it is their right to do with it what they want.

One thing for sure: the Wrigleys will have the last say on any racing on the island, not the people of Avalon or anyone else, and that is the key to the resurrection of the old Catalina or the creation of a new one.