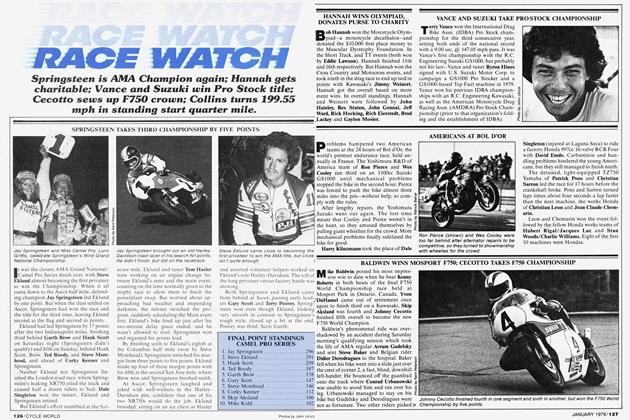

THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

ANOTHER trip to Japan, and each one more spectacular than the last. This issue carries most of my new discoveries under special reports, but I would like to share a few personal views of the whole thing here.

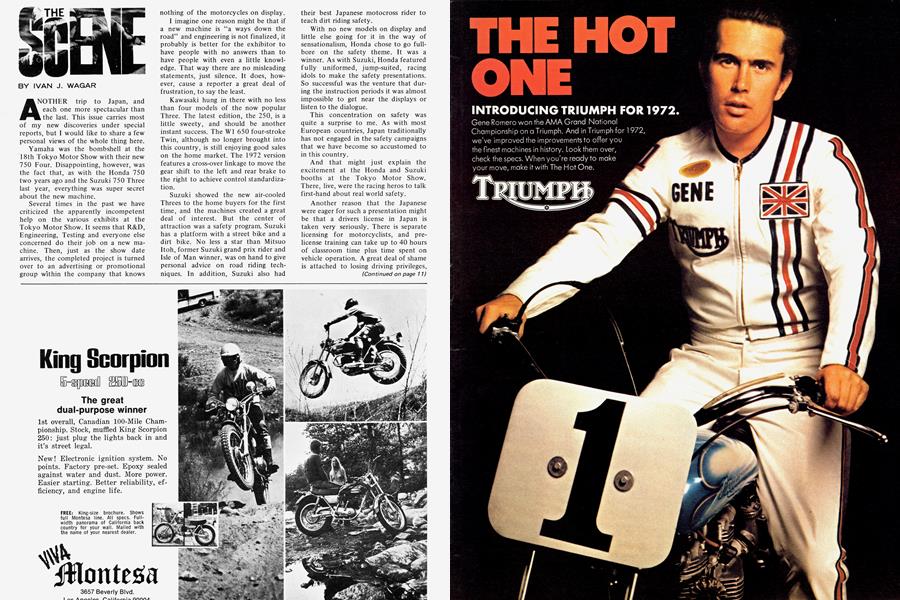

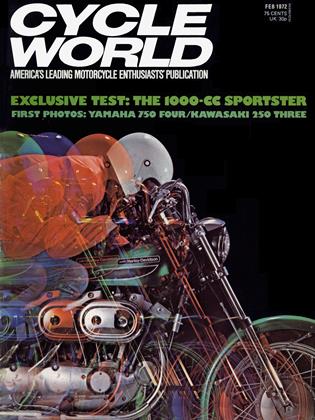

Yamaha was the bombshell at the 18th Tokyo Motor Show with their new 750 Four. Disappointing, however, was the fact that, as with the Honda 750 two years ago and the Suzuki 750 Three last year, everything was super secret about the new machine.

Several times in the past we have criticized the apparently incompetent help on the various exhibits at the Tokyo Motor Show. It seems that R&D, Engineering, Testing and everyone else concerned do their job on a new machine. Then, just as the show date arrives, the completed project is turned over to an advertising or promotional group within the company that knows nothing of the motorcycles on display.

I imagine one reason might be that if a new machine is “a ways down the road” and engineering is not finalized, it probably is better for the exhibitor to have people with no answers than to have people with even a little knowledge. That way there are no misleading statements, just silence. It does, however, cause a reporter a great deal of frustration, to say the least.

Kawasaki hung in there with no less than four models of the now popular Three. The latest edition, the 250, is a little sweety, and should be another instant success. The W1 650 four-stroke Twin, although no longer brought into this country, is still enjoying good sales on the home market. The 1972 version features a cross-over linkage to move the gear shift to the left and rear brake to the right to achieve control standardization.

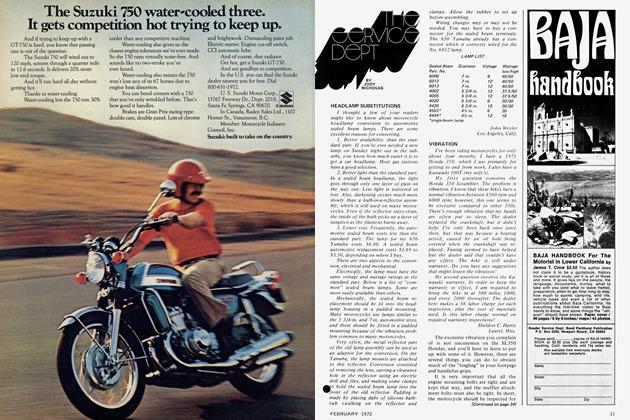

Suzuki showed the new air-cooled Threes to the home buyers for the first time, and the machines created a great deal of interest. But the center of attraction was a safety program. Suzuki has a platform with a street bike and a dirt bike. No less a star than Mitsuo Itoh, former Suzuki grand prix rider and Isle of Man winner, was on hand to give personal advice on road riding techniques. In addition, Suzuki also had their best Japanese motocross rider to teach dirt riding safety.

With no new models on display and little else going for it in the way of sensationalism, Honda chose to go fullbore on the safety theme. It was a winner. As with Suzuki, Honda featured fully uniformed, jump-suited, racing idols to make the safety presentations. So successful was the venture that during the instruction periods it was almost impossible to get near the displays or listen to the dialogue.

This concentration on safety was quite a surprise to me. As with most European countries, Japan traditionally has not engaged in the safety campaigns that we have become so accustomed to in this country.

And that might just explain the excitement at the Honda and Suzuki booths at the Tokyo Motor Show. There, live, were the racing heros to talk first-hand about real world safety.

Another reason that the Japanese were eager for such a presentation might be that a drivers license in Japan is taken very seriously. There is separate licensing for motorcyclists, and prelicense training can take up to 40 hours of classroom time plus time spent on vehicle operation. A great deal of shame is attached to losing driving privileges, which can happen quite easily if due respect is not shown to other road users.

(Continued on page 11)

Continued from page 6

The lengthy driver and rider training programs before licensing result in a very low fatality rate for new drivers. Unlike this country, where up to 70 percent of all fatalities occur within the first six months of operation, Japanese riders rank low in fatalities during the first year. After that one-year period the picture starts to look rather bad and almost approaches our own figures on a vehicle/miles-driven basis.

Initially, it would seem that Japanese statistics should look better than ours when we consider that up to 90 percent of all machines are under 125ee displacement, and that most of those machines are used for transportation at very low speeds. There are, however, many more road hazards facing the Japanese rider, among them narrow streets, blind intersections, concrete drain ditches everywhere instead of shoulders and very large speed differentials. But, despite these dangers, the new rider in Japan has a very good chance of survival. Emerging from extensive training and licensing, usually on a small machine, he is treated with respect by other road users.

Now, however, with the advent of the Honda 750 Four, youngsters are trading in their mundane 360-cc cars for big-bore screamers. I understand the same is true in Italy and even London. Superbikes are where it’s at.

Unfortunately, this new breed of dashing sportsmen is bringing about an increase in motorcycle fatalities, and causing the manufacturers a great deal of concern by it. So much so, in fact that an industry agreement will probably hold engine displacement at a 750cc ceiling. Also the manufacturers are refraining from using performance as a sales tool, relying on engineering, smoothness and comfort as the big sales features.

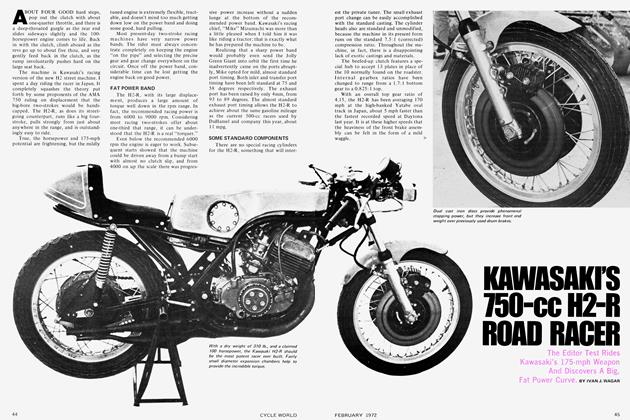

The fun part of the trip was a ride on the mighty 750 Kawasaki racer (covered in this issue), and a stop at Suzuki to see their progress on the new machine for the 1972 AMA season. We will feature the Suzuki racer next month-it’s a beauty.

Suzuki’s race chief, Ishikawa, is grinning from ear to ear these days, for the whole scene is not unlike the heydays of the mid-1960s when Suzuki was so dominant in European Grand Prix racing. No less than 43 employees now work under Ishikawa’s guidance in the racing shop. A stroll down a corridor between an almost endless line of dyno rooms revealed that several were in operation. The whole thing is a veritable beehive of activity. But more on that next month.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1972 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1972 -

Departments

Departments"Feedback"

February 1972 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

February 1972 By Jody Nicholas -

Features

Features"Hicks"

February 1972 By Ben Hands -

Previewed In Japan

Previewed In JapanKawasaki's 750-Cc H2-R Road Racer

February 1972 By Ivan J. Wagar