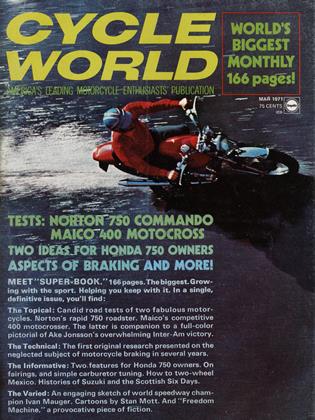

IVAN MAUGER

He Used To Beg For Rides, But Now The World Speedway Champion Tells Promoters . How Much He Wants.

ALAN DIRKIN

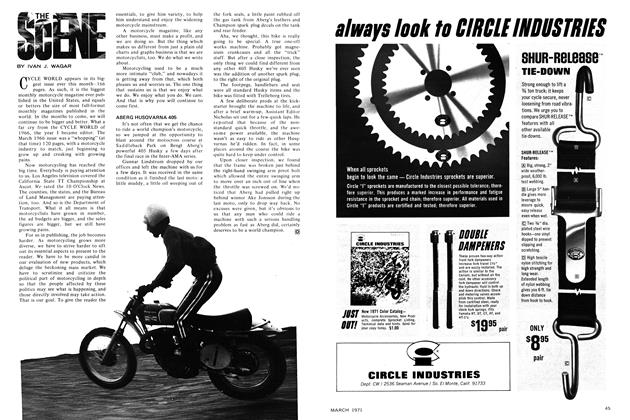

IVAN his MAUGER stocking feet. STANDS The world 5 feet cham7 in pion took a stance with one shoe on and one shoe off in the middle of a motorcycle speedway track.

Hands on hips, eyes wrinkled, he watched Australian champion Jim Airey strong-arming his bike around corners, digging the hot shoe that Mauger lent him into the dirt.

Airey rode like a champion, his rear wheel shooting adobe red rooster tails over the 185-yard Orange County Fairgrounds track, one of ' several horse arenas used for speedway riding in Southern California.

Somehow', Mauger. the chirpy New Zealander w'ho had conquered the world three times .over, stood like a champion.

He did not talk much. Perhaps he was studying Airey’s form, the surface oí the track, or simply savoring his own success.

"Í remember how hard it to save . up to buy a piston ring in those days," —»

Mauger recalled, going back 13 years to his first efforts to break into the British speedway circuit. “The Jawa people provide my machines now and I may seem lucky but, believe me, 1 know what it’s like to whip a second hand JAP with a worn-out engine, bent frame and buckled wheel around the track. That’s experience! It’s pretty hard to break through when that’s all you can afford to ride.” There was no bitterness in the recollection. It was a matter-offact thing to say.

“The English promoters have made it easier for kids to get started nowadays, giving them a chance to ride decent machines,” he remembered. “But they may be missing something. Novices don’t get as deep a knowledge of the sport as I have, and they won’t appreciate it as much as I do when they get to the top.”

At 30 years of age, Mauger is at the top and may go higher than anyone has ever gone in his profession. He has been World Speedway Champion since 1968. No one else has won the title three years in a row. He has been practically unbeatable in that period. His immediate goal is to surpass New Zealand teammate Barry Briggs’ feat of four world championships and then to better the record five titles won by the Swede Ove Fundin.

Ivan Mauger had much to go over as he stood in the middle of the Costa Mesa track. He had to give some thought to defeating the American boys who were spoiling to meet the world champion. They had improved steadily since the sport was revived in California in 1968 and Mauger was responsible for some of this improvement through clinics he had given in 1968 and 1969.

He also had to analyze the track. The oval is half the size of the smallest track in the British League. It is virtually one continuous corner, with no chance to get over 40 mph, and little opportunity to use the skill he has acquired in a lifetime of racing. “A trick track,” Mauger muttered. “It’ll just be a circus act.”

He stood there and watched as Briggs, another member of the international set brought over by Pasadena promoter Harry Oxley, started to cut laps. “It doesn't get any longer, does it?” Briggs laughed as he stopped to rest. “I feel like going around the other way just to unscrew myself.”

“I think the fella with the water cart must have shrunk it a bit,” Mauger responded, poking fun at George Wenn, the track manager who doubles as friend and mechanic.

With that, the world champion walk-

ed toward the pits. He could have been a matador leaving the ring. But the resemblance was not complete. The arrogance that characterizes bullfighters was missing. Speedway is dangerous to be sure, but when you skid handlebar to handlebar into a turn at 70 mph you learn respect, not disdain—respect for your fellow riders and respect for your machine, a 182-lb. oddity that goes better sideways than forward with a 58 bhp engine, but no brakes.

It was Ivan’s turn to ride. “Because we ride on a dirt track, speedway racing is considered a mucky sport,” he said, as he donned the black and white checked helmet that was a garish complement to his red and white leathers. “But, frankly, I bet we are a lot cleaner at the end of a night’s racing than soccer, rugby, or American football players are after a game.”

Mauger worked on starts and slides on a Czech Eso . The engine gulped alcohol and the smeil of burning castor oil was in the air. He got brief but breathtaking acceleration and then wrestled the flimsy machine broadside around corners. His style was European as he lifted his left foot to the peg for the leverage to stand the bike up and point it down the straightaway.

After several laps Ivan traded a few wisecracks with onlookers and accepted a dare to ride a fat-tired Dune Cycle. He sped around the track in it. The world champion was also in Southern California for a good time. After seven months of grinding, competitive riding in Europe, a trip to Southern California has to be some sort of vacation.

He has unlimited enthusiasm for his sport. He talked of the comradeship that exists among competitors. “In Brit-

ish League team racing we race hard against each other. But if a boy has a crash in one race, you lend him a back wheel for the next.

“This same spirit is continued on the international level. The Russian boys can’t buy the good English Lodge spark plugs, and I have personally given three or four Russians spark plugs before racing against them. I don’t think you get this sort of thing in any other sport.”

One of the Russians to whom Mauger gave a spark plug was Gennardy Kurilenko. That was before the World Team Cup races at Rybnik, Poland, in 1969. Last summer, before the European Championship at Leningrad, Mauger had trouble with the valve gear on his spare bike. “Kurilenko heard about it, and you know what he did? He lent me a complete cylinder head. Then I went out and didn’t give him an inch of room on the track. 1 know he would have been disappointed if I had.”

As it turned out, Mauger won the championship without using the spare machine. “But 1 might have had to use that bike and I would have tried to beat him with it,” he stressed.

Like many of his countrymen, Mauger has had a long love affair with speedway. When he was 10 he rode in pedal cycle speedway races in 160-yard long wooden bowls that were popular in those days in New Zealand. His mother was an official of the supporters club in Christchurch and he watched all the dirt track stars of the post-war years.

“When I was 1 1 I got on a speedway team and by the time I was 14 I was captain,” he recalls. “Later I rode motocross and road races but this was only at a club level. What I always wanted to be was a speedway champion.”

Ivan also met a girl called Raye when he was 1 4. At 1 7, he and Raye, then 1 6, were married and soon left on the

12,000-mile voyage to England that all Australian and New Zealand speedway prospects must make if they are to achieve international fame. “Even then I believe Ivan had the world championship in the back of his mind,” says Raye, now a mother of three and wife of a star. “The Australian-New Zealand circuit has no qualifying rounds for the world championship.”

Mauger’s start in England was hardly auspicious. He spent 18 months trying to get rides on the English tracks, and when he did get on the program he impressed no one. They were hard days. He was given a job as a maintenance man on the Wimbledon track at Plough Lane, London. Greyhound racing is also held at Wimbledon and the teenager’s biggest chore was to take down a wire fence that separated the crowd from the speedway circuit twice a week. He also worked as a caster in a factory. Raye got a job, but all the young couple could afford was a second-hand JAP. He was given occasional rides with the Wimbledon club, the Dons, but after two seasons of disappointment, the Maugers returned home.

Down under, things quickly got bet-

ter. In 1960 he signed a contract with Australian promoter Kym Bonython and rode in South Australia for three years, gaining the experience denied him in England. At Rowley Park, Adelaide, he raced regularly against World Champion Jack Young. He won the Victorian Championship, the Queensland Championship, and the Australian Half-Mile Championship. In 1963, British promoter Mike Parker offered to pay the family’s fare to England if Mauger would ride for the Diamonds, a team based at Newcastle-upon-Tyne in Northumberland. Mauger accepted.

Riding in about 400 races a season, he improved steadily. He became a favorite with the crowd at Brough Park, the Diamond’s home track. In 1966, he won the European Championship at Wembley Stadium, London, and finished 4th in the world final. He placed 3rd in the world final in 1967 and then at Gothenberg, Sweden, in 1968 he captured the championship, winning all his five races. He retained the crown at Wembley in 1969 and triumphed again this year at Wroclaw, Poland.

The champion is cashing in on his star status. Motorcycle manufacturers and makers of accessories bid for his endorsement. During the summer he is flown from his home in Cheshire—he now rides for the Belle Vue Aces in Manchester-to tracks throughout Europe for Sunday meetings. “I earn more in a day in France and Germany than I do in a week’s racing in the British League,” he said.

It’s being world champion that counts, and when it’s all counted Mauger reckons the championship is worth $100,000 a year. Briggs enjoys a similar income but few other British League riders top $10,000 a year. The days of begging for rides are long past.

“In the early 1960’s, after returning home from England, I wrote to all the British promoters to see if they were interested in me. Three or four didn’t even reply. When I went back to New Zealand in 1968 for a vacation after winning the world championship, those same people were ringing me up at $4 a minute for half an hour at a time asking me to ride for them. 1 don't bear them any malice. I just don't do them any favors. When they ask me to ride at a meeting I tell them how much I want. When they say it’s too much for a night’s work, I tell them it's for 10 year’s work.’’

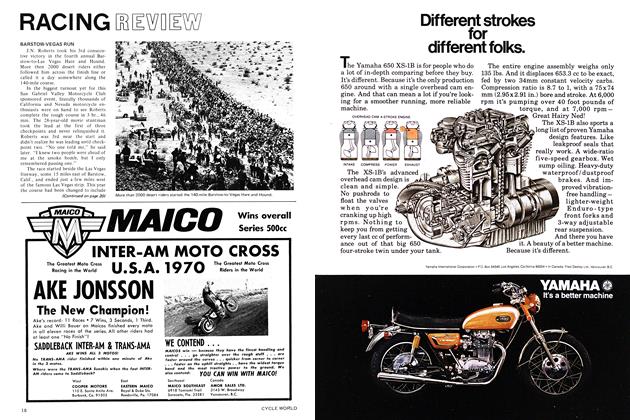

Mauger and Briggs have done much for the sport's current success in Southern California. Speedway was opened at the Orange County Fairgrounds in 1968 and the two New Zealanders were brought over to round off the season. They and other stars, of the British circuit came back in 1969 and 1970. Speedway has now been tried around horse arenas and school tracks at Lancaster, San Gabriel, Indio. Santa Barbara, Bakersfield and Sacramento.

The Friday night races at the Orange County Fairgrounds, Costa Mesa, have been the most successful with crowds averaging 4000 to 5000 from April through early November. Such local stars as Steve and Mike Bast, Rick Woods, Bill Cody and Sonny Nutter compete for shares of a minimum purse of $1000 or 30 percent of the gate. The attendances peaked at 6000 the last two weeks of the 1970 season with the arrival of Mauger, Briggs, Airey and company.

Once again, the foreigners were able to adapt to the short track and won nearly all the scratch races. But they suffered some spills, too. “I must have been in 85 meetings in Europe this year and crashed only twice,” Mauger said. “Here I hav.e competed in two meetings and 1 have crashed each night. Here, fortunately, you only go down at 20 mph. When you crash in Europe you are usually doing 70 mph.”

Mauger said it was the short track that caused the tie-ups, and admitted that it provides a greater spectacle. “In England I don't usually watch the races I’m not entered in, but here I don’t miss one. You never know what's going to happen out there. It’s terribly exciting. I personally prefer to ride a quarter mile track but I would be the last person in the world to tear this one up.”

No one is going to lengthen the track. It’s likely that the only expansion in 1971 will be in the seating. (Ö]