History of Benelli

The Benelli Brothers Have Never Fielded A MultiMillionDollar Racing Effort, But Innovative Designs And Consistent Performances Have Kept Them In The Winner's Circle.

GEOFFREY WOOD

MOTORCYCLE MANUFACTURERS the world over have attempted to gain recognition and thus increase sales by participating in European road racing events. Some have done this by mounting a furious campaign for several years that succeeded in establishing their name with a bang, but many pull out of the racing game, never again to grace the classical grand prix courses. Others have chosen to participate on a more modest scale that can be financially sustained over many years, and this usually results in a history of success, but never outright domination of the sport.

One of the companies that has chosen this last route is Benelli-an Italian concern passionately involved with road racing since they first began producing motorcycles in 1920. The marque has been successful, too. Benelli has modestly but continuously made itself known since the middle l920s.

The story of Benelli actually began in 1 9 1 1 when mother Theresa Benelli, a widow, gathered her SIX Sons around her for a traditional Italian family confer ence. The topic of discussion was the founding of a family business, which would be operated by Giuseppe, Gio vanni, Francesco, Filippo, Domenico. and Antonio. The goal was something mechanical, since the boys were all pretty well captivated by the many new mechanical devices that were being tried out in those early years of the industrial revolution.

The result of this family conference was that Mama Benelli sold some of the family land to finance the purchase of some machine tools, which were soon placed in the family palace at Pesaro on the Adriatic coast. The tiny business at first concerned itself only with the repairing of guns, cars and motorcycles. but by 1919, they entered the manufac turing field by producing a 75-cc two stroke engine that could be mounted on a bicycle. The company also came up with their trademark, a lion crest sup posed to represent courage and the ambition to forge ahead.

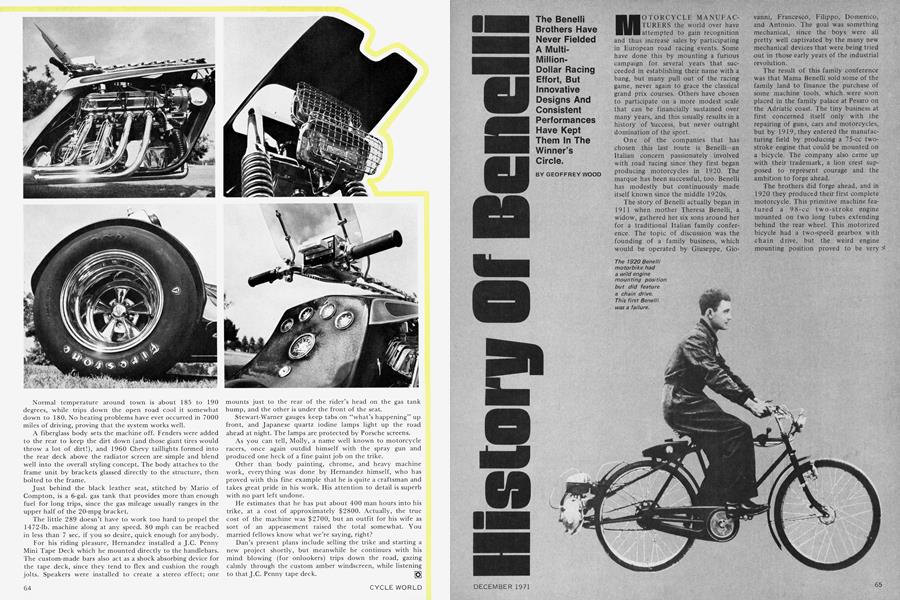

The brothers did forge ahead, and in 1 920 they produced their first complete motorcycle. This primitive machine fea tured a 98-cc two-stroke engine mounted on two long tubes extending behind the rear wheel. This motorized bicycle had a two-speea gearbox with chain drive, but the weird engine mounting position proved to be very weak and the original model was pretty much a failure.

Undaunted, the brothers set about the task of improving their machine by experimenting with a better engine mounting position. They finally settled on a central position for the powerplant-the same as did all the other manufacturers around the world. The young designers then went to work improving their engine in an effort to make it more reliable. In 1922 the tiny Single was increased to 125cc, and then to 150cc in 1923.

This rather archaic looking motorcycle had fairly advanced specifications for those days, with chain drive, a two-speed hand-shifted gearbox, magneto ignition, and tiny internal expanding brakes. The frame was rigid, and the front fork was an early girder type with a single coil spring. The frame was the "vintage" type in which the fuel tank was mounted between the two top frame tubes. The tires were the narrow 2.00-26 size.

About this time the fortunes of the tiny company took a turn for the better when Tonino (an abbreviation of Antonio) began agitating his older brothers for more horsepower. The idea behind all this was racing, and the brothers responded by preparing one of their two-strokes for Tonino to ride. On this primitive bike Benelli launched their racing campaign, and Tonino began to compete in local Italian road racing events.

The first race entered brought some encouraging results, since Tonino came home in 2nd place behind Gino Moretti on a 500-cc Moto Guzzi Single. After this, Tonino settled down to learning the art of road racing, with 1922 and 1923 showing a great number of respectable placings but no outright victories. The other brothers were learning a great deal about designing motorcycles while Tonino raced, so the Benellis were steadily improved.

The brilliant riding and improved machinery were bound to provide a victory some day, since the brothers had applied themselves most diligently to improving their products. The big day finally arrived in 1924, when Tonino won the Poggio Verceto race at Parma. This win on the 150-cc thumper was followed by a win at Bergamo, which helped get Benelli better known throughout Italy. Tonino followed this up with a win in 1925 at the Circuit del Foglia, and in 1926 at the Coppa On Le Mazzolini at Senigallia.

These racing victories naturally helped boost sales, and for the first time, the company had financial resources available to purchase better machinery for their factory. This improved machinery allowed the company to move out of the two-stroke field and into four-stroke production. We might point out here that this was a move that Benelli wanted to make very badly, since those were the days when the new overhead valve and overhead camshaft designs were making the best twostrokes look very inferior on performance.

The first four-stroke Benelli appeared in 1927, and it was destined in time to become one of those very good basic designs which would be widely copied by other manufacturers for their racing machines. The new Benelli was a 175-cc Single with a gear-driven overhead camshaft, which was mated to a three-speed hand shifted gearbox. The engine featured an alloy crankcase and an iron head and cylinder. An outside flywheel was mounted on the left side of the engine. The frame was rigid, and the "vintage"-type gas tank was still used.

This model was produced in roadster trim without lights, since lighting sets were considered to be optional equipment then, and sold well all over Italy. Because of the very good performance of this fine Single, sporting minded Italians really took to the new Benelli.

This ohc Single also proved to be an exceptionally good racing bike, due to its outstanding reliability and fair turn of speed. The biggest problem regarding reliability in those days was valve and valve spring breakage, which was caused by the poor alloy steels available then. This is, perhaps, one of the big reasons why the ohc Benelli was so reliable; its well designed valve gear had much less stress upon it at high revs than did a "push-rod" engine.

This Single was all it took for Tonino to blossom into a real star, and he proceeded to win at the circuits of Monti, Perugia, Vercelli, Verona, Crema, del Lario, del Maria and Spezia. These wins gave Tonino the Italian Championship in the 175cc class, and it also gave Benelli a tremendous amount of prestige in their native Italy. Tonino then won the 175cc class at the Gran Prix des Nations at Monza, which was the first victory in international competition for the marque. This magnificent win helped boost sales to‘a new high, and the company soon left the "tiny" classification.

During these years the company also produced a 175-cc side-valve Single, which was similar to the ohc model except for the engine. The side-valve engine was much cheaper to produce, and offered respectable performance combined with modest maintenance expense.

Tonino had another good year in 1928, when he was once again crowned Champion of Italy in the 175cc class. In 1929 Benelli again dominated Italian 175cc class racing, with Ricardo Brusi winning eight national events and Carlo Baschieri winning the Gran Prix des Nations classic. Tonino made a great comeback in 1930 and '31 by winning the Italian championships as well as the Gran Prix des Nations both years.

During the early 1930s European road racing became terribly competitive, with many factories fielding works teams on technically advanced racing models. Several of the leading marques in international road racing were located in Italy, so the competition had become very intense. In response to this Benelli designed a new racing engine for 1931, and this model also became one of those great designs many others would copy. The engine was still "iron," but it had double overhead cams and a slightly downdraught carburetor. The old hand gearshift was then in the process of giving way to the modern foot shift setup, and a four-speed gearbox replaced the three-speed version. The old vintage fuel tank was also giving way to the modern saddle-type tank that is mounted over the frame tubes instead of between them, so the Benelli began to look more like a modern motorcycle.

During the early 1930s the company began to think seriously of developing an export business, which they heretofore had not benefited from. In consideration of this need to become better known throughout Europe, the brothers decided to embark on a racing campaign all over the continent. Previously the marque had been satisfied with winning races in their homeland, but now they were going to try for bigger game. The first attempts would be modest, though, since the company was still quite small and could not afford a massive assault on the giants of European racing.

The first big race was the 1931 Swiss GP, and Carlo Baschieri surprised all by winning the 175cc class on his new double-knocker thumper. The following year Tonino went afield to capture the Swiss and French events, while in 1933 Raffaele Alberti walked off with 175cc trophies in Holland and Belgium. Alberti also won the Belgian and Italian Grands Prix in 1934, and Benelli continued to dominate the Italian 175cc races. The FIM then dropped the 175cc class from classical racing, and Benelli was forced to retreat to homeland races for the following few years.

This move by the FIM was probably good for Benelli, though, since it gave them time to concentrate on improving their standard production models. All of the success in racing had greatly increased consumer demand for the fine ohc Singles, so the brothers decided to expand their factory and range of models to take advantage of this demand for their product.

By 1936, the range was pretty well standardized with 175, 250, and 500 Singles—all of which had the tried and proven ohc engine. On this engine the single camshaft operated rocker arms, with the rocker arm ends and the valve springs left exposed for cooling. A four-speed footshift gearbox was used, and the fenders, tank, and fittings were all of the "sports" type. These Singles established a reputation for sound workmanship and spirited performance, and Benelli became the fifth largest motorcycle manufacturer in Italy.

During the late 1930s, the company made another big improvement to their range when they produced an optional rear suspension. By 1939 there were six models listed in the catalog-three ohc 250s, two 500-cc side-valvers, and a 500-ec ohc Single. The 250s had a 67 by 70mm engine, with the Sport model having a 58 mph top speed. The Sport S had a beautiful alloy engine with huge fins, and would do no less than 93 mph. The 500s both had 85 by 87mm measurements, with the side-valver doing 68 mph and the ohc model clocking 87 mph. The 250 Sport S was very popular due to its powerful engine and big brakes. It too was an exceptionally fast bike for those days.

In 1936 and 1937 the company did very little in the racing game due to their emphasis on improving production models, but in 1938 they returned to the fray with renewed enthusiasm and a magnificent new racing bike. The new Benelli was a 250-cc Single that had gear driven double-overhead cams, and the engine had an alloy head and cylinder so that the very maximum compression ratio could be used on the 50-50 petrolbenzol fuel. This Single proved to be nearly unburstable, with the peak power being produced at 8200 rpm—good enough for a 110-mph speed. The riders buzzed the engine to 9000 revs when going through the gears or on downhill runs, which gave the Benelli really remarkable performance. It is interesting to note that the post-war Mondial and MV Agusta 125 and 250 Singles had a remarkable similarity to this 1938 Benelli design!

This superb thumper used a magneto for ignition, and a most unusual feature was the oil radiator mounted in front of the oil tank. The gearbox had four speeds, and the cog-swapping was done by an unusual heel-and-toe-type lever. The wheelrims were alloy, and a 3.00-21 front tire was used in conjunction with a 3.25-19 rear tire.

Since the 1935-38 era was the period when Europeans first began using rear suspensions on their racing bikes, it was only' natural for Benelli to try some type of design in an effort to improve road holding. The rear suspension designed by the Pesaro concern proved to be an unorthodox but workable proposition, with a swinging arm being connected to a pair of plunger boxes. The plunger boxes had springs for both compression and rebound, and a pair of friction dampers were used to alter the suspension characteristics. The travel was somewhat limited on this system, but it did allow higher speeds with improved rider control and comfort over rough road surfaces.

The racing scene in which this beautiful Single was baptized had undergone quite a change since the early 1930s, with many European factories fielding works teams on technically advanced models. Grand Prix racing had become a leading sport by 1936, and state financing by Adolph Hitler allowed German marques to produce some tremendously powerful supercharged bikes. The DKW was the European 250cc champion then. Its supercharged two-stroke engine with water cooling and a rotary valve pumped out 40 bhp (in 1939), good enough for 111 mph. Moto Guzzi also had a blown Single on the tracks, so the double-knocker Benelli certainly had its work cut out for it on grand prix courses.

Undaunted, Benelli forged ahead with an aggressive racing campaign and their fine handling Single. Ridden by such pre-war greats as Amilcare Rossetti, Nino Martelli, Francisci Bruno, and Enrico Lorenzetti, the marque racked up many fine victories in the 1938 Italian races over the favored Moto Guzzi. Bruno also headed a Benelli 1-2-3 in the fast Gran Prix dTtalia, with the Pesaro Singles showing a tremendous turn of speed down the long straights. A really staggering fact was that Bruno had averaged a higher speed than had Ted Mellors in the 350cc race, and the 350cc KTT Velocettes were considered terribly fast in those classic prewar days!

This magnificent showing must have had a profound effect upon Mellors, because he later signed on with Benelli to ride their Single in the 1939 Lightweight TT race. This was an optimum situation for the Pesaro concern, since they needed an experienced Isle of Man rider if they were to ever have a chance at winning the most prestigious race in all of motorcycling. Previous to 1939 Benelli had not contested the famous IOM race, mostly because the small company lacked the finances to obtain the services of a top flight rider.

In practice for the 1939 TT, Mellors recorded the second fastest time behind Omobono Tenni on a supercharged Guzzi, with Stanley Woods just behind on another Guzzi. Then came three blown DKW two-strokes. In the race itself the two Guzzi aces streaked into the lead, but on the second lap Ted Mellors passed the ailing Guzzi Singles. Ted then proceeded to widen the gap over the field to win by 3¥i min. from Ewald Kluge on the fastest DKW. Ted's speed was not a record due to rain during much of the race, but this did little to dampen the joy that the Benelli brothers had in their hearts that June day. This victory brought the marque a great deal of fame, and sales of their roadsters expanded all over Europe.

This TT win proved to be the onl> success in grand prix racing during 1939, though, since the supercharged competition just had too much speed on the fast continental courses. The Benelli brothers had realized this as early as 1938, and had gone to work designing a supercharged racing machine. The basic design was sketched out in 1938, and in 1939 the first model was built.

The new racer was a four-cylinder rig with a bore and stroke of 42 by 45mm. It featured double overhead cams and watercooling. On a compression ratio of 12.0:1 and petrol-benzol fuel, this tiny Four screamed to 10,000 rpm and pumped out 52.5 bhp. The frame used was similar to that of the Single, and a girder fork was used at the front. Huge brakes, housed in alloy hubs, were also fitted. The top speed of this fantastic machine was 146 mph, which would have made it no less than 16 mph faster than the blown Guzzi Singles.

Benelli had great hopes that they could secure a world championship with this bike, but fate was to prevent this from ever happening. Due to the small resources at the factory, it was not possible to get the Four ready to race until 1940. By then the dark clouds of war had settled over Europe, and this magnificent racing machine never competed. Sensing that destruction of their country was eminent, the Benelli brothers hid their racing machines in rural areas of Italy near Pesaro. The four-cylinder engine was actually hidden in a dry well on a farm, and the frame in a straw stack in a barn.

During 1940 and 1941 the bombs rained out of the sky on Pesaro; when the damage was done the Nazis pillaged the rubbled remains of tne factory. The machine tools were carried off and the countryside scoured to find the exotic Benelli racers. Mute testimony that at least one Single was carried off popped up in the late 1940s in Germany, when a famous Herrinfolk concern came out with a racing Single that bore an obvious resemblance to the classical Pesaro machine. The fabulous "Four" escaped capture, though, and today it rests on display in the Benelli museum.

After the war the Benelli brothers were tired and discouraged, with their factory a shambles. Aided by the youthful enthusiasm of their sons, they struggled to rebuild their plant. They even went to Germany and Austria to retrieve some of their stolen machinery, and soon the company was again producing motorcycles. The range then consisted of 50to 250-cc two-stroke and four-stroke Singles, which were just basic transportation models for transportation-starved Italy. The first 1000 models produced after the war were actually ex-military BSA, Matchless, and Harley-Davidson models, purchased and then modified to have a rear suspension system.

Due to these severe economic restrictions, it was not possible to resume an active racing campaign right after the war, but by 1947 the pre-war Singles were again banging their way around the Italian circuits in winning form. About the only change made was to lower the compression ratio for "pool" petrol, which took a slight edge off the acceleration and speed.

In 1948 Dario Ambrosini became the Benelli works rider. He proceeded to win four Italian championship races as well as the 250cc class of the Swiss Grand Prix. In 1949 Ambrosini won at Monza and finished 2nd in the Swiss event. Because of these wins, Benelli was encouraged to make an all-out effort to win the coveted world championship in 1950.

The 1950 season started off dramatically, with Ambrosini scoring the closest TT win on record. At the end of Lap 2 Dario was 66 sec. on Lap 3. From then on the brilliant Latin ace learned the course as he raced, and the gap got smaller and smaller until he had Cann in his sights within the last few miles. As they swept past the flag, the faster Benelli just bellowed by to win by only 0.2 sec. at 78.08 mph. Dario also set a new lap record on his last lap at 80.9 mph, surpassing Kluge's prewar record of 80.35 mph.

The rest of the season was a tremendous battle between Ambrosini and the Guzzi riders, with Dario winning at Monza and Switzerland plus taking a 2nd in the Ulster GP. This fine record gave Ambrosini the 1950 World Cham-> pionship, and Benelli also won the manufacturer's award. This was and still is the only time that the Pesaro concern has ever won the coveted world title.

Both Benelli and Ambrosini had hopes of taking the title again in 1951, but fate was destined to deal some very cruel cards. The season started well with several Italian victories, and then Dario came home 2nd in the Lightweight TT. He then went on to trounce the Guzzis in the Swiss event, where his Single showed a great turn of speed. The next event was at Albi in France, where Dario crashed to his death in practice. This loss of their dashing rider so saddened the Benelli brothers that they pulled out of racing for a while. The problem was that they had no one to replace Ambrosini with, since the company was still feeling the financial limitations imposed by their rebuilding after the war. About the only racing wins for the next few years were in the local events on 125-cc two-strokes plus Geoff Duke's 1959 Swiss GP win on a revamped Single.

During the early 1950s the Italian economy recovered to such an extent that motorcycle sales greatly expanded, which in turn provided the incentive for Benelli to improve their designs. This lure of a large market also caused one of the brothers to leave and form his own "Motobi" company in 1953, but in 1962 the two companies merged into one happy family again. During the 1950s the Benelli models became more modern, and by 1961 their 125and 175-cc "Sport" models were considered to be superb machines.

The basic design was a vertically mounted ohv engine with the engine and four-speed gearbox contained in one clean looking case. The frame was a twin-loop cradle type with a swinging arm rear suspension. A telescopic fork was used in the front. The wheelrims were alloy, the seat was a dual type, and the big fuel tank had knee indentaticms— all of which gave the Benelli a sporting look that the Italians dearly love. The 125-cc model was rated as having a 65-mph speed, while the 175 would do 75 mph.

During the early 1960s the Benelli line underwent quite a change after the Motobi company merged with the parent company, since one of Motobi's ideas was to mount the engine in a horizontal position. The bike started out as a 125-cc ohv Single, but in the middle 1960s it was pushed out to a 175. Then came a 200 with a bore and stroke of 66 by 57mm. This was followed in 1966 by a full 250 with bore and stroke of 74 by 57mm, and this model was improved in 1968 when a five-speed gearbox was added.

By 1969 the Benelli line had expanded to no less than 18 models from 50-cc two-strokes up to a new 650-cc ohv Twin. Part of the reason for this expanded range was due to the American market, which Benelli has been actively courting since the middle 1960s. The current lineup of Benellis has two-strokes and four-strokes in a wide range of trim to suit both off-pavement riders and the touring crowd. Sales all over the world have reached a new high.

This expanded sales volume has provided the company with the financial means to once again pursue an active racing policy, which began in 1960 when Ing. Savelli designed a new fourcylinder 250 that had an obvious heritage to the prewar Four. The bore and stroke on this bike is 44 by 40.6mm, and it featured gear drive to the twin overhead cams from the center of the engine. This bike was first raced in 1962 by Silvio Grassetti. It produced 40 bhp at 13,000 rpm and had a six-speed gearbox. Grassetti's only win was at Cesenatico, since the new design often failed to finish.

In 1965 the great Tarquinio Provint joined Benelli, and the development of the Four accelerated. Peak power was pushed up to 50 at 15,000 rpm, and a seven-speed gearbox was fitted. A new frame was also designed, and Provint began to make himself felt in the classical grand prix races. By late 1965 the 250 was churning out 52 bhp at 16,000 rpm, good enough for a 141-mph top speed. Provini stunned the world by trouncing the fast Japanese bikes in the Monza GP that year, but in practice for the 1966 TT he fell off and injured himself so badly that he was forced to retire.

In 1966 the Four appeared with an eight-speed gearbox, and a 322-cc version made its debut in Italian races. The 322-cc model had a bore and stroke of 50 by 40.6mm, and it pumped out 53 bhp at 14,700 rpm. Since then the factory has not been quick to divulge technical data on their racers, but during 1967 and '68 young Renzo Pasolini rode the very fast 250 and 350 Fours to many fine 2nd place finishes all over Europe. Pasolini started off the 1969 season with a real bang, too, for he trounced Giacomo Agostini in four out of five Italian 350cc championship races as well as dominated the 250cc races. Due to Pasolini's dashing style plus a pair of very fast bikes, many experts felt that Benelli was again on the verge of winning a world championship.

The factory, meanwhile, continues to develop a 250-cc V-8 model, which was supposed to make its debut in the 1969 Monza GP. This fabulous machine may have to be changed to a larger displacement, though, since the FIM seems determined to go ahead with their rule to limit 250s to two cylinders and six gears. At any rate the V-8 Benelli is an interesting proposition. [o]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

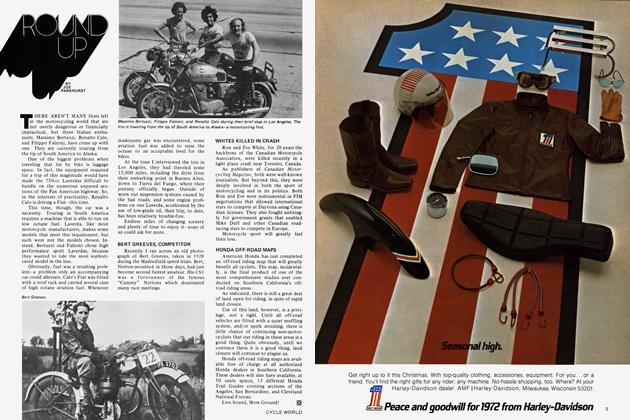

DepartmentsRound Up

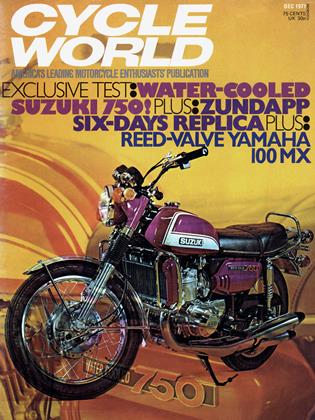

DECEMBER 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

DECEMBER 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

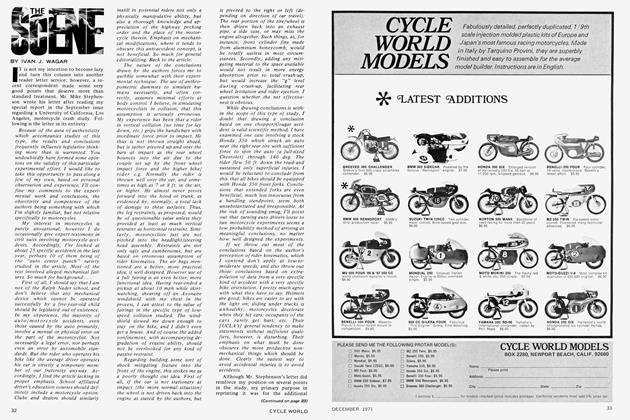

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

DECEMBER 1971 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesViewpoint: the Road Bike In Tomorrow's World

DECEMBER 1971 By Dan Hunt -

Competition

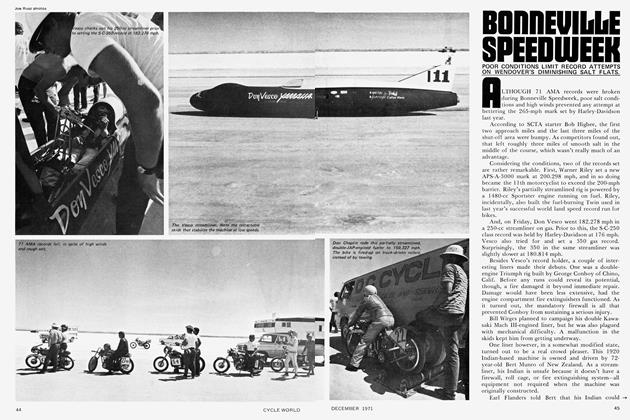

CompetitionBonneville Speedweek

DECEMBER 1971