KAWASAKI SAMURAI A1SS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

When The Performance War Began, Kawasaki Entered With A Hot 250. Three Years Later, It Shows No Signs Of Making Peace.

IT'S BEEN AWHILE since we’ve tested one of Kawasaki’s “small” roadsters, or any 250, for that matter. One reason for the lapse is that the big-bore performance game has been rather distracting. Kawasaki itself has been one of the more aggressive players in this area, with the 350 Avenger and then the revolutionary Mach III.

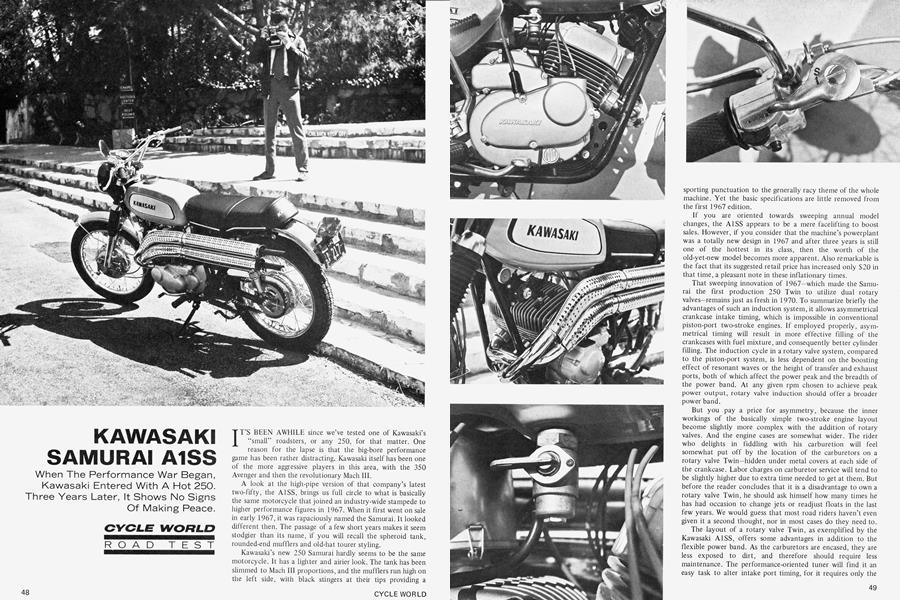

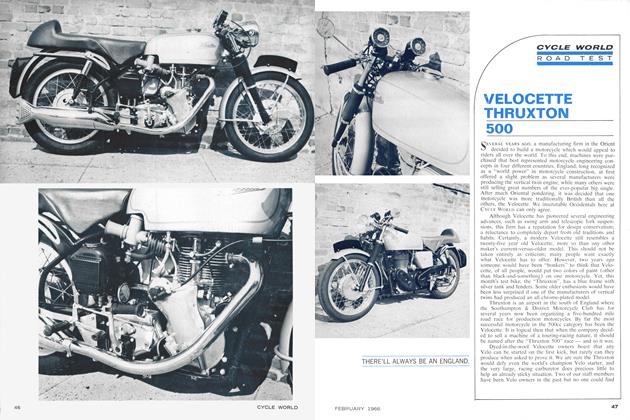

A look at the high-pipe version of that company’s latest two-fifty, the A1SS, brings us full circle to what is basically the same motorcycle that joined an industry-wide stampede to higher performance figures in 1967. When it first went on sale in early 1967, it was rapaciously named the Samurai. It looked dilferent then. The passage of a few short years makes it seem stodgier than its name, if you will recall the spheroid tank, rounded-end mufflers and old-hat tourer styling.

Kawasaki’s new 250 Samurai hardly seems to be the same motorcycle. It has a lighter and airier look. The tank has been slimmed to Mach III proportions, and the mufflers run high on the left side, with black stingers at their tips providing a sporting punctuation to the generally racy theme of the whole machine. Yet the basic specifications are little removed from the first 1967 edition.

If you are oriented towards sweeping annual model changes, the A1SS appears to be a mere facelifting to boost sales. However, if you consider that the machine's powerplant was a totally new design in 1967 and after three years is still one of the hottest in its class, then the worth of the old-yet-new model becomes more apparent. Also remarkable is the fact that its suggested retail price has increased only $20 in that time, a pleasant note in these inflationary times.

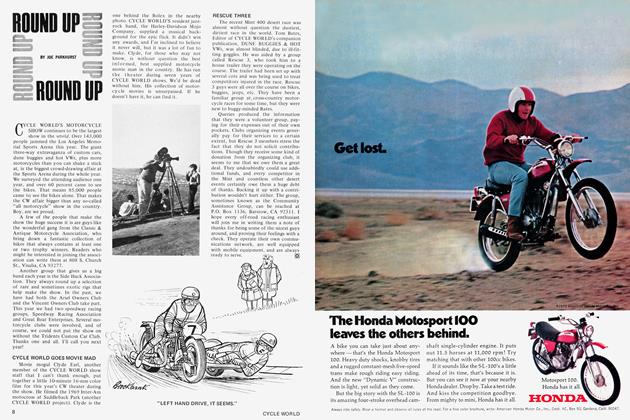

That sweeping innovation of 1967-which made the Samu rai the first production 250 Twin to utilize dual rotary valves-remains just as fresh in 1970. To summarize briefly the advantages of such an induction system, it allows asymmetrical crankcase intake timing, which is impossible in conventional piston-port two-stroke engines. If employed properly, asym metrical timing will result in more effective filling of the crankcases with fuel mixture, and consequently better cylinder filling. The induction cycle in a rotary valve system, compared to the piston-port system, is less dependent on the boosting effect of resonant waves or the height of transfer and exhaust ports, both of which affect the power peak and the breadth of the power band. At any given rpm chosen to achieve peak power output, rotary valve induction should offer a broader power band.

I~ut you pay a price tor asymmetry, because the inner workings of the basically simple two-stroke engine layout become slightly more complex with the addition of rotary valves. And the engine cases are somewhat wider. The rider who delights in fiddling with his carburetion will feel somewhat put off by the location of the carburetors on a rotary valve Twin-hidden under metal covers at each side of the crankcase. Labor charges on carburetor service will tend to be slightly higher due to extra time needed to get at them. But before the reader concludes that it is a disadvantage to own a rotary valve Twin, he should ask himself how many times he has had occasion to change jets or readjust floats in the last few years. We would guess that most road riders haven't even given it a second thought, nor in most cases do they need to. The layout of a rotary valve Twin, as exemplified by the Kawasaki A1SS, offers some advantages in addition to the flexible power band. As the carburetors are encased, they are less exposed to dirt, and therefore should require less maintenance. The performance-oriented tuner will find it an easy task to alter intake port timing, for it requires only the replacement of the standard discs with ones of different duration, or the existing disc may be removed and modified. The intake port itself may be “hogged out,” although this would require disassembly of the crankcases so they may be cleaned of the metal grindings from such an operation.

Finally, the most pleasurable advantage to the touring rider is the almost complete lack of air intake noise. Several piston-port engine makers have successfully overcome the intake noise problem. But the Kawasaki Twin has no problem to begin with, as these sounds are effectively damped by covering the entire intake system with a voluminous air intake housing as an integral part of the engine casing.

While the A1SS engine benefitted from minor refinements, a manufacturer might undertake, in the interest of eliminating minor deficiencies in a new design, one modification in particular—the adoption of capacitive discharge ignition.

Kawasaki’s original approach to ignition was a breaker point system, with a two-lobe point cam; a full wave rectifier converted AC output from the generator, driven at half speed from the primary drive. When some of the original machines had trouble with differing battery charge rate and ignition draw, Kawasaki decided to turn the generator at crankshaft speed, switching to a one-lobe point breaker cam. With the advent of the 500-cc three-cylinder in 1969, which required additional ignition firepower, Kawasaki rationalized its entire line of roadsters to the present CDI system; a signal rotor and pickup coil replaced the point breaker cam. The generator is, as in the previous AÍ, neatly housed behind the cylinders under the air intake casing, and is therefore cooled by a constant flow of fresh air. As the CDI system provides an extremely high (25,000 V) secondary voltage, surface gap spark plugs are used for optimum longevity.

To the end of improving top end performance, port timing has been made somewhat “hairier.” This involves raising transfer and exhaust port height 1.2mm. The present timing figures are: exhaust port opens/closes at 89 bbc/89 abc; transfer port opens/closes at 58 bbc/58 abc; intake port opens/closes at 112 btc/65 ate. Also, the cylinder head now incorporates a squish band to improve combustion of the fuel charge. Carburetor choke size remains the same—22mm.

Little else has been touched, except for exterior trim. Frame and rolling gear components are essentially the same as on the original Samurai. Curiously, the new model has gained about 30 lb. in curb weight, which undoubtedly cancels out the performance gains which might have been realized from the latest engine modifications. To be fair, the engine still felt “tight” when we conducted our performance tests, and this condition may also have limited the results slightly.

Riding the Samurai on the road reminds us how valid the sports car ethic is—i.e. you don’t need great gobs of big bore power to have fun. Just row the gearbox a bit, which is no problem due to its smoothness and the useful spacing of its five ratios, and pitch it through turns as hard as you dare. There is no “yaw” in fast corners. Both front fork and rear damper action are quite good. Moderately low center of gravity and proper geometry allow a decisive attack. Tire size and tread pattern make it easy to adhere to the line you have chosen.

The brakes are obviously effective, judging by the stopping test figures. But the front brake feels spongy at any lever pressure, and gives rather vague feedback to the rider on initial application. Checking back to our notes on the original Samurai, we find that we had similar impressions about braking performance then.

As for the engine, you must pay attention to the rev counter, if you desire to keep it “on the boil.” Yet it doesn’t react adversely to pottering through town in the higher gears at moderate throttle openings. It was an easy starting machine, and quite free of vibration at mile-eating freeway speeds.

We were highly impressed with the quality of the finish and general construction details, like neat welds and rational electrical wiring. The lighting works and the horn is amply loud. Even the tool kit, stored under the hinged seat, is of good quality. Styling is greatly enhanced by the elongated fuel tank and the stainless steel fenders.

The Samurai is even more so a Samurai now, thanks to its new look. It joined the performance war back in 1967, and has managed to keep up the battle quite nicely with few changes. It handles surprisingly well and proves how much fun a bike in the low-priced category can be.

KAWASAKI

SAMURAI A1SS

$715

View Full Issue

View Full Issue