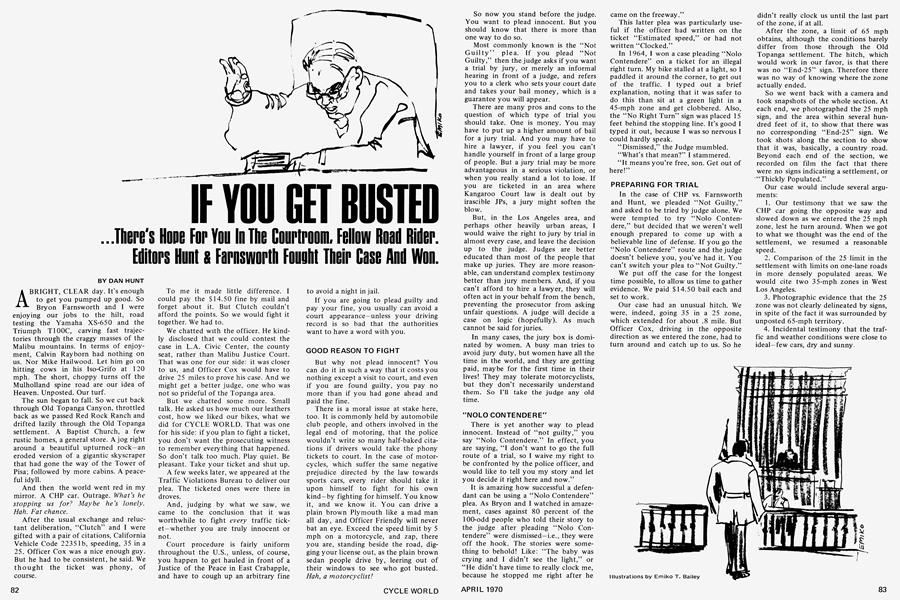

IF YOU GET BUSTED

DAN HUNT

...There's Hope For You In The Courtroom, Fellow Road Rider. Editors Hunt a Farnsworth Fought Their Case And Won.

A BRIGHT, CLEAR day. It's enough to get you pumped up good. So Bryon Farnsworth and I were enjoying our jobs to the hilt, road testing the Yamaha XS-650 and the Triumph T100C, carving fast trajectories through the craggy masses of the Malibu mountains. In terms of enjoyment, Calvin Rayborn had nothing on us. Nor Mike Hailwood. Let him go on hitting cows in his Iso-Grifo at 120 mph. The short, choppy turns off the Mulholland spine road are our idea of Heaven. Unposted. Our turf.

The sun began to fall. So we cut back through Old Topanga Canyon, throttled back as we passed Red Rock Ranch and drifted lazily through the Old Topanga settlement. A Baptist Church, a few rustic homes, a general store. A jog right around a beautiful upturned rock—an eroded version of a gigantic skyscraper that had gone the way of the Tower of Pisa; followed by more cabins. A peaceful idyll.

And then the world went red in my mirror. A CHP car. Outrage. What's he stopping us for? Maybe he's lonely. Hah. Fat chance.

After the usual exchange and reluctant deliberation, "Clutch" and I were gifted with a pair of citations, California Vehicle Code 22351b, speeding, 35 in a 25. Officer Cox was a nice enough guy. But he had to be consistent, he said. We thought the ticket was phony, of course.

To me it made little difference. I could pay the $14.50 fine by mail and forget about it. But Clutch couldn't afford the points. So we would fight it together. We had to.

We chatted with the officer. He kindly disclosed that we could contest the case in L.A. Civic Center, the county seat, rather than Malibu Justice Court. That was one for our side: it was closer to us, and Officer Cox would have to drive 25 miles to prove his case. And we might get a better judge, one who was not so prideful of the Topanga area.

But we chatted some more. Small talk. He asked us how much our leathers cost, how we liked our bikes, what we did for CYCLE WORLD. That was one for his side: if you plan to fight a ticket, you don't want the prosecuting witness to remember everything that happened. So don't talk too much. Play quiet. Be pleasant. Take your ticket and shut up.

A few weeks later, we appeared at the Traffic Violations Bureau to deliver our plea. The ticketed ones were there in droves.

And, judging by what we saw, we came to the conclusion that it was worthwhile to fight every traffic ticket—whether you are truly innocent or not.

Court procedure is fairly uniform throughout the U.S., unless, of course, you happen to get hauled in front of a Justice of the Peace in East Crabapple, and have to cough up an arbitrary fine

to avoid a night in jail.

If you are going to plead guilty and pay your fine, you usually can avoid a court appearance—unless your driving record is so bad that the authorities want to have a word with you.

GOOD REASON TO FIGHT

But why not plead innocent? You can do it in such a way that it costs you nothing except a visit to court, and even if you are found guilty, you pay no more than if you had gone ahead and paid the fine.

There is a moral issue at stake here, too. It is commonly held by automobile club people, and others involved in the legal end of motoring, that the police wouldn't write so many half-baked citations if drivers would take the phony tickets to court. In the case of motorcycles, which suffer the same negative prejudice directed by the law towards sports cars, every rider should take it upon himself to fight for his own kind—by fighting for himself. You know it, and we know it. You can drive a plain brown Plymouth like a mad man all day, and Officer Friendly will never bat an eye. Exceed the speed limit by 5 mph on a motorcycle, and zap, there you are, standing beside the road, digging your license out, as the plain brown sedan people drive by, leering out of their windows to see who got busted. Hah, a motorcyclist!

So now you stand before the judge. You want to plead innocent. But you should know that there is more than one way to do so.

Most commonly known is the "Not Guilty" plea. If you plead "Not Guilty," then the judge asks if you want a trial by jury, or merely an informal hearing in front of a judge, and refers you to a clerk who sets your court date and takes your bail money, which is a guarantee you will appear.

There are many pros and cons to the question of which type of trial you should take. One is money. You may have to put up a higher amount of bail for a jury trial. And you may have to hire a lawyer, if you feel you can't handle yourself in front of a large group of people. But a jury trial may be more advantageous in a serious violation, or when you really stand a lot to lose. If you are ticketed in an area where Kangaroo Court law is dealt out by irascible JPs, a jury might soften the blow.

But, in the Los Angeles area, and perhaps other heavily urban areas, I would waive the right to jury by trial in almost every case, and leave the decision up to the judge. Judges are better educated than most of the people that make up juries. They are more reasonable, can understand complex testimony better than jury members. And, if you can't afford to hire a lawyer, they will often act in your behalf from the bench, preventing the prosecutor from asking unfair questions. A judge will decide a case on logic (hopefully). As much cannot be said for juries.

In many cases, the jury box is dominated by women. A busy man tries to avoid jury duty, but women have all the time in the world, and they are getting paid, maybe for the first time in their lives! They may tolerate motorcyclists, but they don't necessarily understand them. So I'll take the judge any old time.

"NOLO CONTENDERE"

There is yet another way to plead innocent. Instead of "not guilty," you say "Nolo Contendere." In effect, you are saying, "I don't want to go the full route of a trial, so I waive my right to be confronted by the police officer, and would like to tell you my story and let you decide it right here and now."

It is amazing how successful a defendant can be using a "Nolo Contendere" plea. As Bryon and I watched in amazement, cases against 80 percent of the 100-odd people who told their story to the judge after pleading "Nolo Contendere" were dismissed—i.e., they were off the hook. The stories were something to behold! Like: "The baby was crying and I didn't see the light," or "He didn't have time to really clock me, because he stopped me right after he came on the freeway."

This latter plea was particularly useful if the officer had written on the ticket "Estimated speed," or had not written "Clocked."

In 1964, I won a case pleading "Nolo Contendere" on a ticket for an illegal right turn. My bike stalled at a light, so I paddled it around the corner, to get out of the traffic. I typed out a brief explanation, noting that it was safer to do this than sit at a green light in a 45-mph zone and get clobbered. Also, the "No Right Turn" sign was placed 15 feet behind the stopping line. It's good I typed it out, because I was so nervous I could hardly speak.

"Dismissed," the Judge mumbled. "What's that mean?" I stammered.

"It means you're free, son. Get out of here!"

PREPARING FOR TRIAL

In the case of CHP vs. Farnsworth and Hunt, we pleaded "Not Guilty," and asked to be tried by judge alone. We were tempted to try "Nolo Contendere," but decided that we weren't well enough prepared to come up with a believable line of defense. If you go the "Nolo Contendere" route and the judge doesn't believe you, you've had it. You can't switch your plea to "Not Guilty." We put off the case for the longest time possible, to allow us time to gather evidence. We paid $14.50 bail each and set to work.

Our case had an unusual hitch. We were, indeed, going 35 in a 25 zone, which extended for about .8 mile. But Officer Cox, driving in the opposite direction as we entered the zone, had to turn around and catch up to us. So he didn't really clock us until the last part of the zone, if at all.

After the zone, a limit of 65 mph obtains, although the conditions barely differ from those through the Old Topanga settlement. The hitch, which would work in our favor, is that there was no "End-25" sign. Therefore there was no way of knowing where the zone actually ended.

So we went back with a camera and took snapshots of the whole section. At each end, we photographed the 25 mph sign, and the area within several hundred feet of it, to show that there was no corresponding "End-25" sign. We took shots along the section to show that it was, basically, a country road. Beyond each end of the section, we recorded on film the fact that there were no signs indicating a settlement, or "Thickly Populated."

Our case would include several arguments:

1. Our testimony that we saw the CHP car going the opposite way and slowed down as we entered the 25 mph zone, lest he turn around. When we got to what we thought was the end of the settlement, we resumed a reasonable speed.

2. Comparison of the 25 limit in the settlement with limits on one-lane roads in more densely populated areas. We would cite two 35-mph zones in West Los Angeles.

3. Photographic evidence that the 25 zone was not clearly delineated by signs, in spite of the fact it was surrounded by unposted 65-mph territory.

4. Incidental testimony that the traffic and weather conditions were close to ideal—few cars, dry and sunny.

POSSIBLE NO-SHOW

We had yet another hope. That the officer might be so busy that he couldn't attend the trial. It may sound crazy, but just such a thing often happens. If so, all you have to do is say, "As the prosecution has failed to provide a witness, I would like to move that my case be dismissed." And off you go, in most cases. Give your address to the court clerk so he may return your bail money by check.

But we weren't so lucky this time around. Officer Cox did show.

We were called to the bench. The clerk swore the officer in. A prosecuting attorney representing the officer directed opening questions to him. The officer, referring to a diagram of the Old Topanga zone drawn on a blackboard, began his spiel. He said he saw us approaching the 25-mph speed zone at 50 to 60 mph and found a turn-around so he could follow us to see if we observed the speed limit.

I found myself surprised at his estimate of our approach speed, as we had just rounded a partially blind curve that I would not take at better than 35 mph unless I was racing for a $600 purse.

Technically, 50 to 60 mph was not illegal here, as the approach was unposted, but the officer was trying to establish our guilt by implication, and justify his motivation for pursuit. He had smeared us, and now I was really nervous.

His map was also confusing. I had looked at a road map, which showed the zoned stretch running North-South. But he had drawn it running East-West.

TACTICAL BLUNDERS

Neither Bryon nor I asked about the discrepancy. We should have. It offered an excellent chance to discredit the officer's testimony. It doesn't matter whether we were going 35 in a 25 or not. Court procedure is an abstract game, which has little to do with Absolute Truth. If you discredit a witness on even the smallest point, credibility of the remainder of his testimony suffers in the eye of the judge. So we blundered slightly.

In an attempt to establish the officer's expertise, the prosecutor elicited the testimony that Cox had previously been a motorcycle officer for a year and a half and presumably would be a good judge of estimating the speed of a motorcycle.

But he also blundered. He asked the officer about his roadside conversation with the defendants. Officer Cox replied that we had told him we were road testing motorcycles for CYCLE WORLD magazine. His intended inference was that road testing was a Bad Thing, but he had also indirectly established our own expertise. At this point, we didn't need to be recognized as expert riders, but if things went bad for us, we could use it later.

After the officer testified that he had caught up to us and obtained a "rolling clock" just before we left the speed zone, it was our turn to cross-examine him.

Proudly, I whipped out my pictures and asked the judge if I could introduce them as evidence.

"Yes, you may/'

I showed them to the officer and the prosecutor, and asked if they were recognizable as the area in which the violation occurred. Things went haywire for a moment, as I had about 20 prints, all out of sequence, and had to describe each one to Cox. Both the officer and myself huddled over the table below the judge's bench and conferred in friendly tones as I pointed out each shot.

The judge didn't dig this at all: "What's going on here, anyway? Speak up. You're addressing the court, not holding a private conversation!"

I gasped.

The prosecutor groaned.

Officer Cox straightened up and tried to go back to his side of the table, but bumped into me.

Finally, the prosecutor said, "Okay, okay. We will stipulate, Your Honor, that the pictures are of the area in question."

That was one for our side.

"So what do you want to do with the pictures?" the judge snapped.

I wasn't quite sure what he meant and didn't say anything.

"Come on, bring them here. Let me see them."

I approached the bench and showed him how there was no End-25 sign near where we were "clocked,"how the settlement wasn't that much different from the unposted area at either end, and that there were no other cautionary signs than the sole 25 mph posting at each end of the section.

"So all you see is the back of the sign, eh?"

"Yes, Your Honor. And regardless of what speed we were doing, it is interesting that this 25-mph zone is less populated and carries less traffic than some one-lane roads in the city that are posted at 35—like Kenter Avenue and Bundy, for instance."

"Hmmmm. (Pause.) Does the prosecutor have any questions to ask the defendants."

THE TIDE TURNS

The prosecutor wasn't sure. He was thinking about those pictures. "Ah, yes, Your Honor. I'll direct my questions to, ah, Mr. Farnsworth."

A great choice, for us. Farnsworth could sell an icebox to an Eskimo.

Since the prosecutor was now unsure that the officer's "rolling clock" at the end of the speed zone would be held valid, he questioned Farnsworth about our entry into the zone.

"How fast would you say you were going as you approached the 25 mph sign?"

"I'd say about 35 to 45 mph," Bryon said, which was, in fact, true. Rather than stop here, Fast-Mouth Farnsworth plowed onward before the prosecutor could ask the next question. "When I saw the officer, I slowed down, naturally, because I was entering this residential area. When I figured I was out of it, I speeded up. But there's no End-25 sign and our pictures prove it. Even though the zone ends. There are no more signs. That means you could ride all the way to the coast highway at 25 mph, even though it's really 65 there."

"Hmmmm," went the judge.

The prosecutor, now off-pace, asked, "When you passed the 25 mph sign going into the settlement, how fast do you think you were going?"

The judge interrupted: "That question is highly speculative, prosecutor. Mr. Farnsworth, you don't have to answer that if you don't want to."

Bryon didn't. He's no dummy.

"Any more questions?" the judge asked.

"Yes, Your Honor," I said. "Officer Cox, how would you describe traffic conditions on the day of the alleged violation?"

"Ah, I'd have to say it was light." "And the weather?"

"It was sunny and dry."

"And how long did it take you to turn around when you spotted us going the other way? That's a rather narrow road."

He smiled triumphantly. "A very short time. I was lucky. I came upon a turn-around just after I passed you and spun the car around on the dirt very

quickly."

But I pressed on, trying to make my inferred point about how fast he would have to travel to get a clock on us.

"How many seconds would you say that turn-around took, officer?"

"I can't really say," he replied. Then he looked at his watch and unconsciously pantomimed the action of spinning the car around on the dirt. It was quite amusing.

Waving an impatient hand, the judge snapped "I think that will be quite enough. I rule Not Guilty. Insufficient Evidence."

I was thunderstruck. Was this for real?

"Mr. Hunt and Mr. Farnsworth, see the clerk to get a refund on your bail money," the Judge said. "And you, officer. Get some proper signs up there. Your job is to protect the citizens, not to give out tickets because people can't figure out what is happening. How can you expect them to read the back of a sign?"

It was for real. He was chewing out poor Officer Cox. Right there. In front of God and Everybody. I almost felt sorry for him.

"Thank you, Your Honor," I said. "Sorry I took so much time with the pictures."

"That's quite all right," the judge nodded. "That's what you're here for." We had made use of our judicial system to fight for what we thought was right. And why not? Like the judge said, it is our judicial system. For all of us. Bryon and I had won.

And you can bet we feel pretty damn good about it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

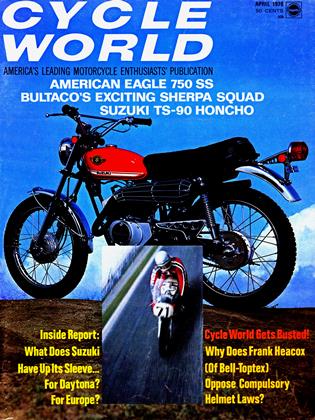

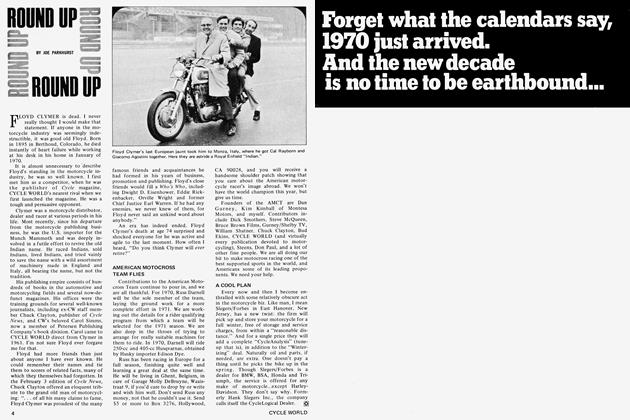

DepartmentsRound Up

April 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

April 1970 By John Dunn -

Features

FeaturesA Mind of Its Own

April 1970 By Bob Ebeling -

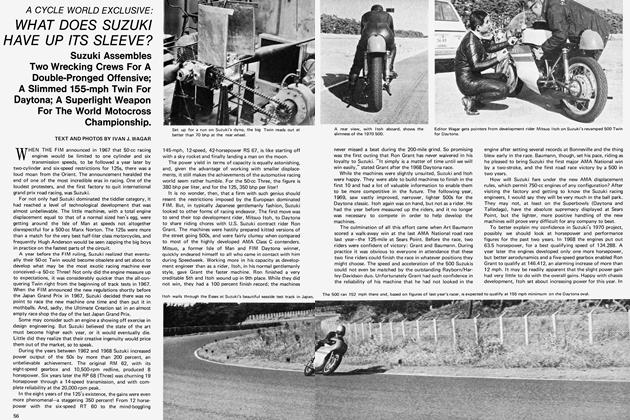

A Cycle World Exclusive

A Cycle World ExclusiveWhat Does Suzuki Have Up Its Sleeve?

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar