Frank Heacox Sells Helmets. Lots of Them. But He Opposes the Helmet Law. He Is, You See, A Motorcyclist. And We Can Thank Our Lucky Stars.

April 1 1970 Dan HuntFrank Heacox Sells Helmets. Lots of Them. But He Opposes the Helmet Law. He Is, You See, A Motorcyclist. And We Can Thank Our Lucky Stars. DAN HUNT April 1 1970

FRANK HEACOX SELLS HELLS HELMETS. LOTS OF THEM. BUT HE OPPOSES THE HELMET LAW. HE IS, YOU SEE, A MOTORCYCLIST. AND WE CAN THANK OUR LUCKY STARA.

DAN HUNT

An Interview On The Most Important Matters Affecting You, The Motorcyclist, Today.

MOTORCYCLING is in a critical state. The immediacy of the statement may not seem readily apparent. But you can see little symptoms here and there.

Anotner helmet law. A dirt track that withers in a major population area. The closing of a forest area to trail bikes. A national champion declaring that he's going to race cars. A road rider wondering what he's going to do for kicks this Sunday—something new, but where is it?

Why?

The question begs asking. And it begs answers. Why are all these little things

happening? Especially when motorcy cling is in its boom years.

So we went to Frank Heacox for some answers.

Frank is a motorcyclist. He raced at Catalina and won his class in the Big Bear run one year. But to him, all motorcycling is sport, not just racing.

He is the man who heads what is potentially one of the most powerful organizations in the history of American motorcycling-the Motorcycle Industry Council-a new group that can do much to set things right.

Before that, he was one of the more liberal members of the AMA Executive Committee. Since then, he has watched much of the work he did for the AMA-research, program studies-lie fal low, waiting to be executed.

Frank Heacox opposes compulsory helmet laws. It is a curious position, at first glance. He is vice-president and general manager of Bell-Toptex. They make crash helmets. But Heacox has good reasons for his position.

i~no ne nas positions anout many things. He doesn't hedge. He's not a politician in that word's usual connota tion, because he seems too direct. He's not overly concerned about Frank Hea cox. Rather, he's concerned about his "pet peeves." For most people, those kind of peeves are for airing in bars or over weekday lunches, soon forgotten.

For Frank Heacox, a pet peeve comes with a built-in compulsion to do something about it. That compulsion is evi dent, even in the manner that we conducted the interview. We talked about broad issues, which ofttimes lead to a great set of generalities. I prepared a loose outline of topics which I thought would lie in Frank's area of concern. He was otherwise unprepared and we had not talked about them before.

Yet, the interview proceeded in an extremely well organized manner, and Heacox had specific examples to go along with his general statements. At any time, it seemed he could produce from a file here, a closet there, a study or committee report to back his state ments. He had obviously been thinking about my questions for years, and in most cases had been doing something about them.

The interview is long, yet represents a taping session which lasted barely more than two hours. In five parts, it dis cusses the helmet law, the state of professional motorcycle racing, the road rider in relation to the AMA, the trail rider, and the Motorcycle Industry Council's relevance to all these issues.

As a whole, it emerges as a position paper, motorcycling's version of the State Of The Union message. It is our hopes, our fears and what we can do about them. If we want to.

PART I: THE HELMET LAW

Hunt: It seems curious that, although you are associated with Bell-Top tex, one of the major manufacturers of helmets, you are well known for active ly opposing compulsory helmet legisla tion for motorcycle riders. Why?

Heacox: The most important reason is because the laws as they are being passed now are aimed at a minoritymotorcyclists-and without real good reason except that it is a minority.

I personally feel that the use of safety helmets was progressing nicely. I'm very upset, being a motorcycle rider of many years standing, that this thing was done, as far as I can tell, without real regard for trying to save the maximum number of lives, rather just aiming it at putting some pressure on a minority. This is the thing I object to most. If they really want to save lives they could make the use of seat belts mandatory in auto mobiles and probably save 50 times as many lives every year. - -

Hunt: Of course, that would be a particularly unenforceable type of seat belt law.

Heacox: Oh, there would be many ways to doit, I'm sure.

hunt: I-Ia, yes, you could have a red light that blinks on top of your roof whenyouhaven'tbuckiedup!

1-leacox: me tfllng is, even it it can't be enforced, you know that there would be many people who would abide by it if it were law. And if they were involved in an accident, thrown out of the car, or if it were otherwise obvious that they hadn't fastened the belt, they could be subject to loss of insurance.

But at any rate, what I'm getting at is the idea that they have singled out motorcyclists to try and make something mandatory. In my opinion, they could look into many other areas and save more lives.

Hunt: Perhaps it would be interesting to have you draw a parallel at this point. What would be the fair equivalent to the automobile driver, given the fact that all motorcyclists must wear helmets as required by law? A seatbelt fastening law?

Heacox: Actually, if we're talking about injuries to the head—and death due to injury to the head—I'd say we have very nearly as high a percentage of them in automobile accidents, and so you could draw exactly the same parallel. Let's make it mandatory for them to wear helmets in cars, and see what sort of reaction you get from the majority!

We are talking about 2.5 million registered motorcycle owners in the U.S. But there are more than 82 million registered automobiles.

You would have it fought by the drivers themselves because they don't want to wear a helmet. Comparing the use of helmets by motorcyclists and automobile drivers is a good parallel, because most of the people killed in automobiles are killed due to head injuries.

Hunt: And most of the people responsible for motorcyclists' injuries happen to be automobile drivers. Which makes the whole legislative situation seem to be quite a cop-out.

Heacox: Very true!

Hunt: Do you, as a helmet manufacturer, stand to profit from compulsory helmet legislation?

Heacox: No, although I suppose that is what many people must think, every time they get hit with a helmet law.

From a commercial point of view, we are not in favor of mandatory laws, because it caused the sale of helmets for a period of several years to be compressed into only a couple of years and drew in a tremendous number of imports and new manufacturers to satisfy a temporary increase in demand for helmets.

Now, that demand has been pretty well satisfied, some 40 states having laws in effect, and we find today that many helmet manufacturers and helmet importers are now "discontinuing." They are in financial difficulty and many of them have gone out of business, or they've consolidated with another manufacturer to try and come out with something that can stand the reduced market conditions.

Hunt: Of course, from the point of view of time, it is almost impossible for any large company to meet a sudden demand imposed on them by the passing of a helmet law.

Heacox: Exactly. There's no way that it is practical for us. We can't obtain and train enough people—especially if we're doing it for only a short period of time.

A Good Parallel: Make it mandatory for automobile drivers to wear helmets and see what sort of reaction you get from the majority!

Hunt: That brings up another point. As this demand situation has happened already due to legislation in 40-odd states, one might guess that certain manufacturers have produced and sold many helmets that are possibly not up to the best standards.

Heacox: It's entirely possible that this is true, because, unfortunately, the facilities for policing the quality of helmets is virtually nonexistent. I say this in spite of the fact that we do have the Safety Helmet Council of America's certification program. But unfortunately that program got started so late that it didn't really have the opportunity to do the job it could have done.

As a result, people have been selling helmets and advertising them as meeting certain standards—state or otherwise— when in fact many people in the helmet industry do not feel that they meet these standards.

But there is no agency other than the state, I assume, retaining the right to check this, if they see fit, that has been doing this and the states have not been doing it, generally speaking.

Hunt: How has the Federal Government participated in the setting of standards?

Heacox: The Federal Government did suggest, long after many states already had their own helmet laws, that they consider both the Z90.1 standard and the MS&ATA standard, which are entirely different standards. So you can say, in fact, all the Federal Government was saying was: Get a helmet law with some sort of a standard.

Hunt: What is your opinion of the Z90.1-1966 standard?

Heacox: Until a few weeks ago—when the Snell Foundation announced that they have a new higher standard that will go into effect July 1, 1970—the Z90 standard was the highest standard in the world, really.

Although it is the highest standard, it still can be passed by a helmet that will absorb two direct impacts in the same

site at a maximum velocity of 13.4 mph. This makes it really a low standard. And it is a standard which is aimed at road riders and road use, not one that is intended for high performance use.

Hunt: It is not a racing standard?

Heacox: In our opinion, absolutely not.

Hunt: One may make the argument that even for a road rider, the Z90 standard might be a little low.

Heacox: Exactly. If a person was riding along on his little 50-cc machine and somehow got popped off at 35 mph and immediately went head first into a solid object—a curb, or a wall, or an automobile—a Z90 helmet would not protect him.

Hunt: How does American practice compare with European manufacture?

Heacox: I think we find as much variation in helmets that come from foreign countries as there is in the United States. Actually, there are some very good foreign made helmets and there are some that are extremely bad.

The main problem we all face is that the consumer is really at the mercy of the manufacturer. Unless a standard is followed, the consumer has no way of being sure that what he is wearing isn't just something to keep the rain off his head.

It may look like a helmet, feel like a helmet, but the construction of the shell and the impact absorbing medium may not do the job that it is intended to do.

Hunt: What will the new, higher Snell Foundation standard be and how does it affect y our production? Or will it?

Heacox: It will affect our production and we're in favor of it, actually. The new Snell standard calls for an increase of 1/3 in the impact energy level and at the same time they are decreasing by 25 percent the allowable transmitted energy of the impact. So, when you put these two factors together, they have stiffened up their standard considerably. Prior to this, Snell used the Z90 standard, as did the Safety Helmet Council of America. Now they've gone further.

I say it's good because I think there must be a series of standards. It makes sense to me to have an extremely high standard for a person who is exposed to impacts at literally hundreds of miles per hour as compared with a person who is going to be riding on the street at maybe a maximum of 65 to 70 mph.

We're looking forward to the new standard. It will probably mean that certain models of our helmets will not meet this higher standard and eventually will not be acceptable for competition purposes. But other models that we have will meet it without any question and these are the ones that we really recommend for competition anyway.

Hunt: In a way, it seems amusing to me that helmet laws are made mandatory when you consider the relatively low impact resistance figures of helmets manufactured to the highest standards. A helmet is a bonus, at best, but it doesn't make up for the fact that you shouldn't have crashed in the first place.

Heacox: Certainly not. I can guarantee that those of us in the helmet industry absolutely do not want people to think that because they are wearing a helmet, they can ignore all the safety practices, traffic regulations and so on. This is not the case.

Hunt: Nonetheless, some people take that attitude.

Heacox: Yes. You'd be surprised how many people have written us letters, saying that they were wearing one of our helmets when they had an accident. They state in the letter that the helmet saved their life. But then they're upset because the helmet was damaged in the process and they think that we owe them a free replacement!

Hunt: Incredible!

Heacox: The state of the helmet manufacturing art right at this time is on the average far below what is necessary. We're doing everything we can, of course, to try to upgrade these helmets. But people have the mistaken idea that if they buy a helmet, any helmet, and put it on, they are immune to injury and can do things that they wouldn't ordinarily do if they didn't wear the helmet. This is certainly false.

Hunt: What do you see in the way of future improvements in helmet construction?

Heacox: Unfortunately, there are no new miracle materials available to us at this time. We certainly wish we could find new materials and new techniques, and we are constantly trying to find them. But for the foreseeable future, I can't see any revolutionary changes coming.

The simple fact now is this: as the helmet gets a little larger, a little heavier, and usually a little more expensive, you get proportionately more protection out of it. We can make helmets right now that will absorb impacts at pretty high velocities, but these helmets generally are heavier, bigger and more costly, than the average person wants to put up with.

Hunt: An example would be the Bell Star.

Heacox: Exactly right. The Star, without question, is, in my opinion, the helmet capable of absorbing the most impact energy of any in the industry.

All helmet manufacturers are subject to the same restrictions, placed on them mainly by the public, but in some cases by government, and that is the matter of size, weight, cost and appearance.

As for shape, the ideal one because of its natural strength is one that is closest to a sphere. We've tried to keep that in mind in determining the shape of our helmet, yet modify it slightly so that it does the best job possible of fitting the average human head. So we have a compromise on this spherical shape idea.

The most revolutionary is our Star, and in reality all that has been done with it is to add material over the face to extend the coverage. We feel that this is vital, because the facial bones—bones around the eyes, and the jawbone—have in some cases have been instrumental in causing injury or death. They are connected either directly or indirectly to the cranial cavity and that's where the real damage takes place.

Hunt: It would seem to me that the "ideal" helmet protection would involve having a guy put on a Bell Star and then climb into a plasticene suit surrounded by a mucous membrane four feet in depth surrounded by another plasticene suit.

Heacox: Well, that may sound ridiculous but this is about what it amounts to.

I'll give you an example that ties right in with this sort of thing, and that is in regard to race cars that have a roll cage.

We think that one of the most dangerous things that have come along, from the standpoint of its effect on the helmet, and therefore the head of the wearer, is a rollbar that is situated in close proximity to the helmet.

You can see that if a car flips, and the roll bar strikes the pavement followed immediately by the helmet striking the rollbar, the effect is just the same as if somebody stood back with about a 10-foot length of pipe and swung it and hit somebody in the head. It causes a forced concentration in a very small area of the helmet. Naturally, you want to try to spread the impact over as much of the head as possible.

No, compulsory law is not good for the helmet business, and leaves open the possibility that the market may be flooded with below-standard gear.

So we try to point out to the people who build cars that they should build a "second helmet" into the car. The inside of the roll cage should have a shell over additional padding material, and the head should be restrained so that it can only come in contact with a contoured padded surface that closely approximates the padded, contoured surface of the helmet.

Hunt: It would be interesting to see the results of using a bonded liner monocoque chassis and body in a "safety car. "

Revelation: the world's stiffest helmet standard is not a very high standard. Not at all.

Heacox: Well, you're beginning to see that already in automobiles with padded dashes and visors.

I can see the day coming when helmets for automobile passengers might become a reality. It seems to me that the consideration here is: can the automobile manufacturer build the interior of a car as though it's a big helmet, just as you mentioned, and at the same time provide some means of being able to see outside.

Now, if they eliminate the need to see outside, then the entire inner surface of the car can be very thickly padded so that the inside of the car will serve to protect the people.

Hunt: I believe we call this type of car a subway.

Heacox: Hah, yes! I doubt very seriously whether the vast majority of automobile passengers would elect to go that way. I'm not just sure which way it's going to go. Maybe it will all be solved because they eliminate automobiles completely.

Hunt: Of course, there is a point of no return in the degree to which you provide for safety.

Heacox: Yes, I agree. There will always be some situation where the measures you've taken won't work.

I think we have to look at all the things that deal with safety—whether it be motorcycles, cars, planes, buses—and play the odds. To best advantage.

In this day and age, there's a certain amount of danger in everything we do. We have to decide between living in a padded closet with 100 percent filtered air, doing nothing but existing, or getting out and living under the conditions that we face and trying to set something up so that we have a reasonable chance of surviving. Somewhere between the extremes is the right way to go. I'm sure that the government's intentions are in our best interest, but sometimes they seem to go overboard.

Hunt: But we can safely conclude that using a helmet is a pretty good way for a motorcycle rider to play the odds.

Heacox: Very definitely. I think that a person who resists wearing one, just because they don't like it, or because it costs a few dollars, is not playing the odds in his favor.

I might point out a new bill introduced by Assemblyman Foran of California that does not call for mandatory wearing of helmets. But it does specify that if a helmet is sold in California that it will meet a certain minimum standard prescribed by the California Highway Patrol. I support this, my company does, and I think I speak for the Safety Helmet Council as well (Heacox is president of that council—Ed.). We're behind this basic idea and we want to work with the CHP to establish as high a standard as possible consistent with the state of the art. If such a law is passed, a person can rest assured that he is buying about as good a helmet as one can possibly buy.

I wish the Federal Government had issued guidelines for a standard prior to the time that the first law was passed by the State of New York. As it now stands, we have 40 states with laws and there's quite a variety in regard to standards among them. It would certainly make it much better when a person who lived in the state of California, without any law, decides to go across country. At least he knows that if he buys a helmet that meets a national standard he'd be free of arrest in any state that he goes to.

It's grossly unfair for a person in the United States to be subjected to a wide variety of traffic laws, without good reason.

The mandatory helmet laws are typical examples of premature legislation. They are written by people who do not have the necessary background to write such a law. The reason that they do it often seems to be politically motivated. A motorcyclist makes good campaign fodder. He's a minority. The politician can satisfy the pressure to sponsor bills to support his record in office without fear of being bitten back.

It's unforgivable.

PART II: THE RACING GAME

Hunt: Bell-Toptex has for quite some time supported professional motorcycle racers with contingency money. But, overall, motorcycling has not benefited from contingency support, or endorsement patronage, to the same extent as auto racing. It has often been remarked that bike racers "work harder" than the car people and, in some cases, draw more spectators than cars running on the same tracks. Why do we then have this poor money situation in the motorcycle sport, and how might it be improved?

Heacox: First of all, it is a shame for the professional bike racers to be paid such modest prize money, and contingency money. It's entirely too small. These people put on a sensational show. And they can sometimes outdraw the cars by 3 to 1.

I feel that the cause of this difference between automobile racing and motorcycle racing goes way back to the original idea in American motorcycling that even professional racing should be a club sponsored, or club promoted event. That it should be something that's done by the local people, on a Sunday afternoon, and if they collect $100 to divide up among all the competitors, this is fine.

That is not right, in my opinion, and I think we have got to look at professional racing for just what it is. And that is a professional sport. We should get it into the same league with auto racing, golfing, tennis, or any one of the other professional sports.

The AMA could execute a basic program to solicit contingency money quickly and inexpensively, says Heacox. But, for some reason, the executive committee has been lax.

Hunt: Can the contingency money situation be improved?

Heacox: The matter of contingency prize money happens to be a pet peeve of mine. I've repeatedly tried to encourage the AMA to solicit contingency prize money from every conceivable company that in any way is engaged in supplying parts or accessories for motorcycle racing.

Hunt: That is an interesting point, because I have the impression that the AMA has been traditionally opposed to any sort of promotion or solicitation of this sort.

Heacox: For some reason, they've never seen fit to go out and solicit.

Now, I can guarantee you that automobile racing associations-NASCAR, USAC, and the other large, prosperous associations that pay good prize money-solicit this sort of thing. NASCAR, for example, goes so far as to solicit it ahead of the season. They then print their entry blanks, listing the contingency prize money and the donor right on the entry blanks, so that before each race the entrant knows exactly what he

"The AMA has to be alive and recognize in advance, if at all possible, what the public is showing an interest in."

can win. And they do many things to try to give credit to the donor of contingency money, whereas the AMA appears to resist this practice.

Hunt: As a former member of the AMA executive committee, you must be familiar with the way in which such a policy could be instituted. How is it going to come about? Does the executive committee have to tell the central office, "Here. This is our policy, and this is what you're going to do. "?

Heacox: This is correct. All the rules that have to do with the actual racingengine size, use of brakes, etc.—are the business of the competition congress.

But a matter such as the solicitation of contingency prize money is a matter for the executive committee to investigate. It is their duty, in fact. If they rule in favor of it, then they can instruct the executive director to provide a program for soliciting contingency money.

For some reason, in spite of the fact that it has been suggested—I personally have written letters to key people—it actually has never come to pass. The executive committee has been lax.

Hunt: Is it partly because of the budget available to the AMA -or lack of it, rather?

Heacox: A solicitation program

would cost money, true. But I think that it would be very inexpensive and not take very much time for the AMA to prepare a list of people to solicit, and a letter saying that "we urge you to participate" and mail that out. That would certainly be an opener.

Hunt: A mailing like that would only take a few weeks to accomplish.

Heacox: That's correct. And I think that something like this could be done, and done quickly and inexpensively, if a decision were made to go that way.

Now if you're talking about actual personal contact by a representative of the AMA with each of the potential contingency prize money donors, then, of course, you're talking about a fairly expensive approach.

Hunt: Of course, that could be done in later years, presumably as the sport would grow because of increased contingency money, and there would be more money available to expand.

Heacox: Yes, we have to creep before we can run.

Hunt: Can you expand a little on why, then, we can't seem to be able to even creep? Who, or what, is holding back such a simple directive?

Heacox: I think that it goes back to what I was speaking about earlier. And that is the attitude that motorcycling should be a small, club type of activity and shouldn't be put into the hands of professionals, who can take motorcycle racing and make it the big thing it deserves to be.

Hunt: This club ethic sounds like it's a holdover from some fine old gentlemen trying to resurrect some good times they had 30 years ago.

Heacox: That's about what it amounts to. Let's face it, the biggest portion of motorcycling activity is not going to be club oriented. It's going to be professional racing, witnessed by spectators who don't even belong to a club.

The way I look at it, you should ask, "What percentage of the automobile activity is directly club oriented?" It's a very, very small percentage. I think that gives us a clue. It isn't really necessary to try to have the clubs sponsor professional events. A professional event has to be done by professionals.

Hunt: Does this attitude of professionalism imply that local expression of AMA districts must go by the boards?

Heacox: Absolutely not. In fact, just the contrary. At the present time, each district is merely geographical and informal. You do not have any officially recognized organization in each district at all. A district organization—or sports committee—is little more than a sort of "amicus curiae". And we need it to conduct not only racing but a full range of motorcycling activities. But I don't feel it has to be primarily club oriented. Heacox feels that the AMA should actively pursue contingency support for its profession al racers. Example: NASCAR goes so far as to line up contingency prize money donors ahead of season, and itemize prizes and donors on the entry blanks.

Hunt: In other words, the district organizations should resemble the AMA central office in structure? And they should in effect be promotional groups which should go out in the field and be more aggressive?

Heacox: This is the type of thing I have in mind, yes. I do feel that there must be, for the expansion of the AMA, district organizations, but not necessarily so deeply involved with the club aspect of the thing.

If we're talking about professional racing in particular, I'm not in favor of the district concept. It should be handled as it would be handled for professional golfing, baseball or anything else:

You have an organization which has an adequate staff to travel nationally, and investigate all the potential of various areas, find the right promoters, select the proper locations, do the proper promotion, so that the whole thing is carried out in a truly professional manner. I don't think that we have that, and here's an area where the AMA's lack of funds is a serious handicap. They don't have enough people back there. If they did have they'd be much better off.

This leads me to believe that we must reevaluate the entire dues structure, professional license fee structure, the whole works, so that we can get enough people to do the job properly. And pay these people a reasonable wage.

Hunt: It almost seems like we're in a state of emergency.

Heacox: It is! No question about it. Reform is many years overdue.

Hunt: Living near Ascot Park, as I do, I tend to view that track's decline as a hotbed of flattrack racing as a syndrome of the larger problem. With a great deal of sorrow, I might add.

Heacox: I'm glad you brought up Ascot and flat track racing. This raises another point directly connected to what we've been discussing.

That is the fact that the AMA seems to have a negative approach to ferreting out and exploiting the interests of the general public, with regard to professional racing.

As an example, I think that it has been pretty well demonstrated that the public would like to see professional motocross. And that came about—I won't say by accident—but not at the direct desire of the people who are in positions of power in the AMA.

I feel, too, that there is a possibility of reviving speedway, or Class A type racing.

What I'm getting at is that the public's interest in types of racing seems to change. To go in cycles—if you'll pardon the pun.

Flattracking, on the half mile dirt tracks, as we've seen it for many, many years, is becoming passe. Both the AMA and the industry should have people

who recognize this fact.

Hunt: Neil Keen's not going to like that!

Heacox: No, I don't think Neil feels that way about it. We've discussed this very point and Neil is in favor of all types of racing that happen to be of interest. If the people want to see flat track, then let's give them flat track. But if there's an indication that we can develop new, vital enthusiasm in another type of professional motorcycle racing, by all means, let's not be several years late.

Hunt: This year will be an interesting test of that sort of thinking. The national calendar is literally jammed with road races, compared to previous years. And now we have three motocross nationals.

Heacox: I think that this is the type of thing that is overdue, without a doubt. The AMA has to be alive and recognize in advance, if at all possible, what the public is showing an interest in. And not resist development of that kind of a program, but encourage it.

That brings up another subject. I think we need to recognize that there are differences in motorcycle racing. Each of them has its own place. And it would tend to generate more interest in motorcycle racing in general if we were to promote all of these and develop a national champion in each category— not insist that a person be a road racer, a flat tracker, a short tracker, a motocrosser, a TT racer, all at the same time.

All of these require somewhat different skills. If you want to have what amounts to an Decathlon motorcycle champion, well fine, have that.

But I think that we all recognize the fact that the Decathlon man usually doesn't get as much attention from the public as the man who wins the 100yard dash, the mile and the other specific events.

Hunt: That is a beautiful parallel.

Heacox: We are beginning to tend to recognize "separate" champions in flat track, TT, and road racing, and now, three or four years late, a national motocross champion.

I certainly wouldn't be opposed to working out some system—either by direct competition or through some sort of a point weighing system—to come with a grand national champion. But we should have separate championships.

PART III: THE ROAD RIDER

Hunt: A major part of the motorcycle business has nothing to do with racing whatsoever. It consists of the lowly road rider, who outnumbers his dirt riding brethren and his racing brethren. What do you think of his status at the moment, and what do you think can be done to improve on that status, and perhaps bring him a better sense of identification?

What I'm doing, I guess, is answering the first part of the question by implying that he is a member of a rather amorphous group, right now.

Heacox: Well, you're certainly right in presuming that the road rider is not getting a fair shake, as far as attention from the AMA and the industry.

I think that we all tend to gravitate toward the more exciting, more glamorous end of any sport, and I think this is particularly true in regard to the road motorcycle rider. More attention should be paid to him.

But it is perhaps more difficult to come up with programs that will be interesting, and acceptable, to the road rider.

How about the $2 man? Heacox: "We're losing sight of the fact that the AMA is made up of individual members who have the right to individual considerations."

However, I would question your statement that road riders are in the majority. I think you will find that the number of them that use their motorcycles for street transportation or for just the sheer pleasure of riding down the highway, through the mountains, or wherever, is less than half of the motorcycles that are registered.

(Editor's Note: A random sampling of 2,463 CYCLE WORLD readers conducted in 1967 revealed the following information: of those owning just one motorcycle, 54 percent responded that they used their machines for general transportation, 46 percent used them for road riding, 30 percent for trail riding, and 15 percent for competition. The results total more than 100 percent since most readers use their machines for more than one purpose.

Road machines of one sort of another accounted for more than 70 percent of the bikes owned by the responding readers, but due to multiple ownership, more than 45 percent of those responding also own machines for dirt riding and competition.)

I really feel that the place of the motorcycle is as a fun machine. I don't mean to imply that a person cannot have fun riding on the highway, never

getting a wheel into the dirt. There are many types of activities that can be developed for these people. This is one area where club activity in the past did a fair job but I think that proper organization, even without the clubs, can make it better in the future.

Hunt: Proper organization-by whom and for whom?

Heacox: This is what I meant by having local AMA organizations at a district level—under the direct control of the AMA headquarters. They would work in conjunction with the newly formed Motorcycle Industry Council, individual manufacturers and so on, to set up interesting activities for the individual road rider.

I feel that we've got to do this—over and above the club activities. There's a tendency for people to not want to join motorcycle clubs. A lot of people would like to take an interesting and colorful tour on their bike, but they don't have the time to devote to joining a club, attending meetings, and participating by the giving of their time to the club and its activities.

I think that these functions should really be put on by the AMA and their officially recognized local district organizations, and also by the manufacturers.

Hunt: This brings up an important point about the future role of the AMA. Do you think the AMA should concern itself with competition alone, or do any of the people involved in the AMA really care about non-competition activity?

Would the Motorcycle Industry Council-as it is more directly involved with the people who sell motorcycles, on which these "amorphous amateurs" road ride or indulge in casual trailingbe the better source for such programs?

Heacox: I don't feel that the Motorcycle Industry Council should be directly involved with this.

Certainly, individual MIC member companies can participate in providing assistance to the groups putting on these activities, but I don't think that the MIC should do it itself.

It is something that should be directed and controlled more by the riders themselves, rather than the industry, but definitely with industry's help and guidance.

Hunt: It seems to me that you have a paradox here, in that you want to have something controlled by the riders, but you acknowledge the fact that a good many riders don't want to get into an organization where they have to devote time. Yet you say the primary voice of manufacturing and distribution-the MIC-shouldn't involve themselves directly either. Somebody's got to do it. How can we make it work on the profit motive?

Heacox: If it's going to work, the AMA must have programs that are of

sufficient interest to its members—the AMA's members, the two-dollar members, not the local club members—so that they feel they are getting something of value from the AMA.

Hunt: What would that be?

Heacox: First of all, going to bat for the rider in things that have to do with legislation and other matters affecting the rider directly. The helmet law is probably the prime example.

Secondly, putting on and arranging for various activities within his area and on a national basis that will be of interest to him. Again, these things need not be competitive in any way. They should be things of interest—new ways for him to enjoy his motorcycle.

Hunt: Can you envisage on a more specific level the forms which these activities would take? Much dissatisfaction has been voiced with the "Death Valley-29 Qualms" sort of road run. Don't you think there should be alternatives to this?

Heacox: I don't think we should seek to replace this type of run. There are certain people who feel that the socalled Gypsy Tour runs are the ultimate.

Hunt: But is there another choice?

Heacox: Oh, I think there are many other choices. The organized mass event may be coming to an end because of the problems of moving that many people safely over the highways, but, in its place, I think of things like the European Youth Hostel circuits, or bicycle circuits, where arrangements are made so that if a person wants to take a vacation on his motorcycle, he can get from the AMA information that tells him: places to camp; hotels or motels that welcome you; restaurants; all the things that will allow small groups to take a variety of different types of trips, either long or short.

Hunt: The tie-up with hosteling

sounds like a novel idea. I used them quite a bit during my two bike trips through Europe. Had a great time and met many wonderful people. Yet I was on my own. And knew I could always find an inexpensive, fun place to stay.

Heacox: Well, I think that sort of thing could be worked out over here. It's sort of the "Bronson" approach, only maybe not quite as glamorous, and perhaps doesn't afford all those "unusual" opportunities to get involved, although I suppose your imagination would be the limit.

But I think we're going to have to look at this type of thing in the future. When you try and put several hundred motorcycles on the highways, all going the same place at the same time, I think the police are going to go out of their minds.

Hunt: And other people may not dig it, either.

Heacox: So we've got to do these things on an individual basis. I don't feel that there's any problem in setting these things up. And the AMA-somebody in it—is the right place.

Hunt: In respect to your hosteling idea, perhaps the most logical thing would be for somebody in the AMA office to contact the American Youth Hostel Association for information, which the AMA could disseminate.

Heacox: And first convince the hostel association that this is a desirable thing. I'm sure that if you walked in cold— especially in a few years gone by, maybe not so much now—they would have said absolutely no, "don't want those dirty old motorcyclists coming into our place."

But I think that the time is now ripe for this to take place. And it's just one example of many ways that road riding could be stimulated, if the AMA would do it.

And I think that it's something that the rider has to pay for. I think he has to realize that if he wants to have fun on his bike, and do things that require some organization, he has to be willing to put in his fair share. And then he has a right to expect that it will be set up properly so that he can enjoy it.

Hunt: It seems that the AMA would do well to raise the $2 member fee.

Heacox: That $2 fee is ridiculous. You can't even begin to contact the man and send him his card for that amount of money in this day and age!

Hunt: Yes, in the time that the AMA fee has remained at $2, inflation has more than halved the value of that money. The price should just about double every 10 years at present inflation levels.

Heacox: Additionally, I feel that any member of an organization such as the AMA should automatically receive some periodic information. The lack of communication in motorcycling is just as guilty of causing problems as anything else. We've got to communicate.

And yet, an AMA member plunks down his $2, he gets his card, and then, if he is lucky via the grapevine, he might find out something about what the AMA is doing. If he does not subscribe to American Motorcycling magazine (the AMA magazine) or one of the good motorcycle publications, then he is out of it. He receives nothing, automatically, free of extra charge, to tell about the things we have been talking abouthelmet legislation, a motorcycle-hostel arrangement throughout the country, what the other problems are that face the road rider, and how, by joining together, AMA members can take steps to do something about them.

So this is another reason the AMA fee needs to be increased. I'm not saying the communication from the AMA should be a magazine. I personally feel that it should not be. It should be free of advertising, and should come to the person automatically, as much as the AMA news is now coming automatically to the clubs. But the club news is not adequate communication with the individual member. We're losing sight of the fact that the AMA is made up of individual members who have the right to individual considerations.

PART IV: THE TRAIL RIDER

Hunt: Trail riding is a fantastically booming sport. But I see a trend: more trail bike activity, more enraged conservation club members, and, the result, fewer available trails.

Heacox: Again, you have brought up one of the things that the AMA needs to be working on, and given us another reason that they need more money and ought to raise the membership fee-so that they can get competent people to go out and negotiate to ensure that there will be areas where the motorcycle trail rider can enjoy his sport.

I think that trail riding is the real example of where motorcycling is at. It can be enjoyed by the entire family. And it gives you a mobility that the hiker never has had and never can have.

Trail riding: "I think that everybody has the right to enjoy an area, assuming that they respect that right and treat it in the fashion that it should be treated."

Hunt: That raises a good point. In many places-like California-conservation groups have managed to give trail riders a short deal on the amount of trail mileage available for motorcycles.

It seems to me that the logic is turned around. A motorcyclist can cover 50 to 100 miles a day, relaxing and stopping along the way, where a hiker, at best, can do 20 to 25 miles a day. Yet most of the time the hiker is given the majority of the trails. Sometimes there is good reason for doing this, but in other cases not.

Heacox: You're absolutely right. I'm certainly in favor of trying to maintain many of our areas in as natural state as possible. But there isn't much sense in having an area in its natural state if you can only see the edge of that huge area.

I think that it has to be a give and take proposition. The motorcycle fraternity must realize that they've got to protect the areas, comply with the regulations, prevent fires, prevent littering, and all the other things that ensure that we will be permitted to remain there.

The fact that we happen to be on a motorcycle, instead of walking, or on horseback, or in a four-wheel drive vehicle, is just a matter of choice. It's the same individual, the same person, who has the desire to enjoy the great outdoors.

Hunt: Apropos, we received a letter from a ranger who said he's tired of stepping on horse droppings! So maybe they should ban horses from the trails.

Heacox: Hah, that's beautiful! Well, I'm sure that the horse people would say that they're tired of smelling exhaust fumes. But the bad must be taken with the good!

I think that everybody has the right to enjoy an area, assuming that they respect that right and treat it in the fashion that it should be treated.

I can see the logic in maintaining some small percentage of the total area available completely free of any type of motor vehicle. The rest of the area should be made available under controlled conditions, to everyone.

PART V: THE MOTORCYCLE INDUSTRY COUNCIL

Hunt: What is the major advantage of the Motorcycle Industry Council?

Heacox: I feel that any industry that is going to progress, expand, and develop must have a strong industry association. In this case, we have the MIC.

The council was recently formed as the result of a merger between the Motorcycle, Scooter and Allied Trades Association (MS&ATA) and the Motorcycle Safety Council. Each of these groups represented about half of the motorcycle industry, speaking in terms of dollar volume. At times they were at loggerheads.

The Federal Government, for example, in its new drive on safety, needs to have one voice it can listen to with regard to motorcycle activities, as it does with all other vehicle activities.

The government expressed the desire for the industry to "get together". I'm pleased to say the MIC has done just that. We're safe in saying that we have better than 95 percent of the industry represented in the MIC. To my knowledge, this is the first time in history that this has ever happened.

What's even more exciting is the fact that all of the people have approached this with a new openness, frankness and spirit of cooperation that I think we can really build on for the future. It will open up unlimited possibilities for motorcycling in all directions.

Now that the industry is united, we can go to every agency that has anything to do with motorcycling and assist them to better the sport.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

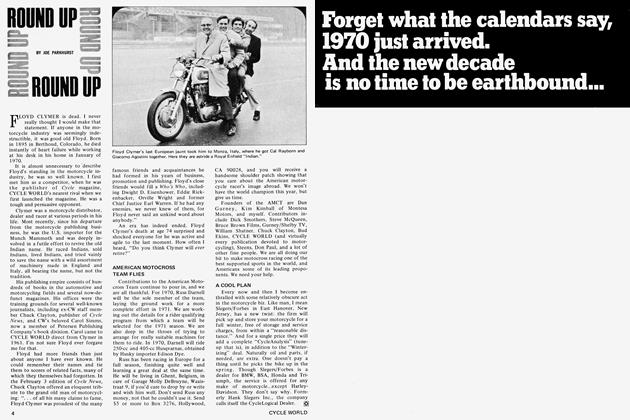

DepartmentsRound Up

April 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1970 -

Departments

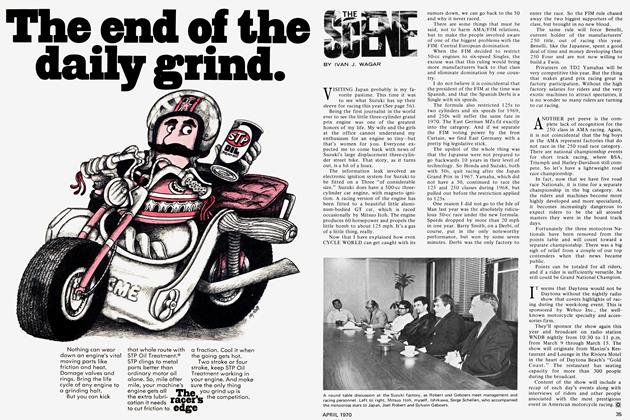

DepartmentsThe Scene

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

April 1970 By John Dunn -

Features

FeaturesA Mind of Its Own

April 1970 By Bob Ebeling -

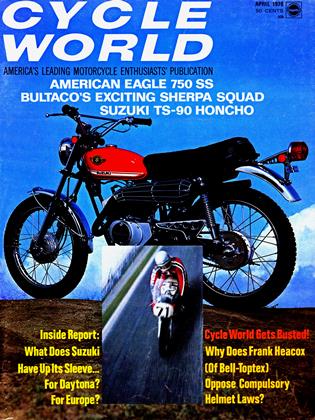

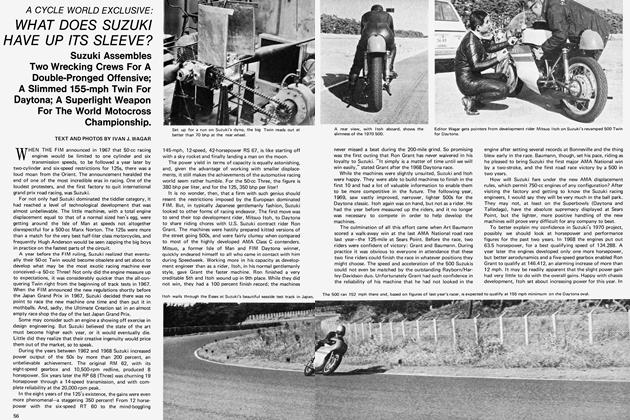

A Cycle World Exclusive

A Cycle World ExclusiveWhat Does Suzuki Have Up Its Sleeve?

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar