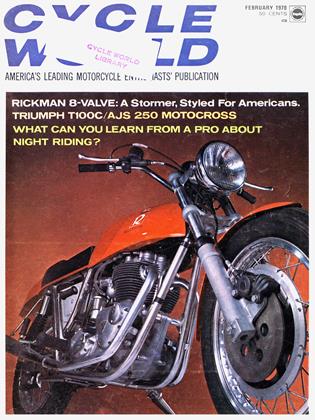

TRIUMPH TROPHY 500

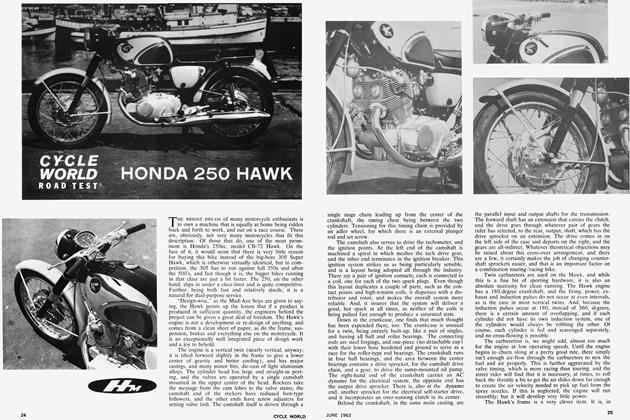

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Triumph’s Finest, After 32 Years, Is Still Triumph’s Finest, But How Much Longer Can It Endure?

WHO NEEDS A 500 Triumph? After all, horsepower is where it's at, right? You pay a little more for a 650 or 750 and you get your bhp. It's that simple. Sorry, but we don't agree. We have a certain feeling about the 500. Partly because 500 cc is the classic limit in international competition, and was the mainstay of AMA "Class C" racing until 1969. It's an economical size, big enough to thrill, yet compact enough to be an extension of man's spirit.

That feeling runs even deeper. Down to archetypal level. If the dentist gave us sodium pentothal we wouldn’t babble about 650s or 750s. Our hazy reveries would be all 500s. And particularly the 500 Triumph.

Ivan remembers... He raced a kitted Tiger at the Island in 1952. Before that he had a sprung hub 1948 Tiger 100, which he cafe-raced on the roads of back country Canada.

“For its day, it was smooth, handled reasonably well and had good brakes. (Crafty smile.) There was nobody on the road from Belleville to Kingston who could stay with me. (Frown.) No, I better not say that—we’ve got a safety image to keep up.”

“Aw come on, Ivan, it’s only a reverie.”

“Okay, okay. (Smile.) Make that: nobody stayed with me, day or night. Hah!”

Clutch remembers. “It was my everything bike. I raced it in Class C, 500 Sportsman, and cow-trailed on it. I liked a lighter bike. I once traded a 40 straight across for a T100C. It’s part of the club of growing up. You have to have a 500 Triumph. Funny, what turned me on about it. The way it spins the rear wheel. Doesn’t accomplish a damn thing, but it makes your heart go ‘woooo!’ ”

Dan remembers his 10 months straight on a ’62 in the wilds of Europe. The image still lingers—the shocked faces of two carabinieri, fumbling to start their Guzzis, as a joyous levi-clad American wearing an odd red jersey flashed by on a dirt road detour, showering gravel. “Oh, the way you could pitch that thing on those windy European roads!”

And then there’s Joe. Matchless Joe. Maico Joe. Ducati Joe Métissé. A lover of Singles. But he admits that he, too, had a Trophy, back in ’49.

“I loved it. Lots of power, and it shifted good. And I liked the sound. I had it all chromed and decked out in red ignition wire—you remember, like all the guys used to do. Then I’d go out in the dirt and beat hell out of it. I remember riding an enduro at Calabasas and almost getting castrated on the luggage rack. (Wistful pause.) Yes indeedy, it was a girl pleaser.”

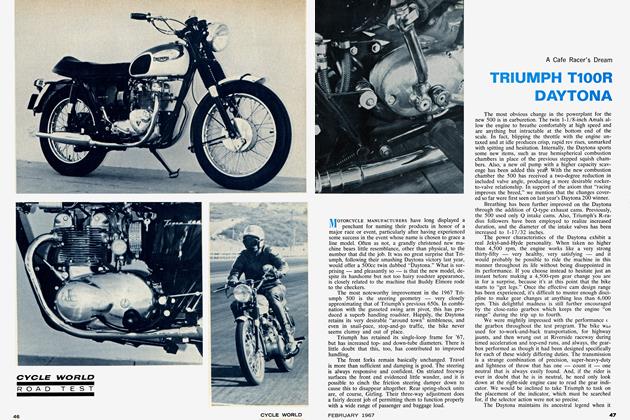

Joe doesn’t have to worry about the luggage rack. It’s gone. A “refinement” in reverse. But that 500 Twin is still here, a design conceived 32 years ago. Enough years and memories to make it a relic. Overshadowed as it is by its bigger brethren, the 500 has somehow persisted. Perhaps it owes its continued existence to American racing, culminating with Triumph’s big assault on Daytona in 1966 and 1967. Except for the massive effort to improve the Daytona racer’s handling and performance-things which were passed along to the production models-the 500 would be just another 500. Today, it is still Triumph’s finest machine. A basically sound and well proportioned design.

There are two 500 Triumphs. The T100R Daytona roadster with dual carburetors and low mufflers is the fastest, capable of 90-mph quarters in the 14s and 105-mph top speed. Yet the single carburetor, high pipe T100C “Trophy” is more popular in spite of lesser performance. Versatility is what sells it. The Trophy 500 handles as well or better than any production road bike made. Stripped of lights, and regeared, it makes an excellent cow-trailer or fireroad machine, good enough to win the national enduro championship for seven straight years.

An initiate to the 1970 version of the T100C will likely be impressed, first of all, with the bike’s quiet smoothness. It purrs docilely around town below 50 mph, and pulls easily at low rpm. This latter characteristic makes the bike easy for the novice to ride (and a welcome relief to those who are used to keeping the revs up to get torque). Mechanical noise is fairly low. Surprising, as the cylinder barrel appears to be aluminum, like the head and cases. But it is really iron, which absorbs noise.

Over 55 mph, the purr becomes a buzz. This, of course, is the reason for the popularity of the bigger 650, which only has to turn 3500 rpm at 65 mph and therefore gives a more relaxed sensation than the 500 at that speed. However, the buzz of a 500 is nowhere near as disconcerting as that of a 650 running at the same engine speed. The 500 is a better balanced engine, with lighter pistons, rods and valve gear. The displacement is near ideal for a Twin. “Oversquare” bore/stroke dimensions (69 by 65.5 mm), instituted in 1959 along with in-unit transmission, also make it an inherently smoother and more efficient machine than the long-stroke (71 by 82 mm) 650 Twin. After you get over the initial apprehensions having to do with turning an engine at high rpm, you’ll find that the T100C buzz remains pretty much the same at 85 mph as it is at 55 mph. Sweet music. And the bike won’t complain about being run all day at 70 mph.

The engine has a hidden dual nature. You could ride all day and never know about it. Then, one day, you decide to “let her wind.” And bang, a whole new rush of power comes in at about 5000 rpm and lasts to about 7500 rpm when the valves begin to float. Fantastic. Good low rpm torque, yet an almost cammy rush at 5000 rpm. This is a characteristic of Triumph’s Q-profile camshaft, which was incorporated in the 500 in 1963. It is now used in both the 30and 40-inchers, but that “Q” effect seems most pronounced in the 500s, which have a “hemi” type head designed by Doug Hele for the Daytona racers and subsequently adopted in the T100R in 1967. It wasn’t until 1969 that the T100C got the benefit of the new head.

Now it takes the mere addition of a bolt-on manifold and a second carburetor to bring the T100C head up to T100R specifications. But there is still one important difference. The hotter T100R uses the Q-cam for both intake and exhaust, where the T100C uses the Q-cam for the intake only, and a milder N-type cam for the exhaust.

Bearing similarity to the Jomo “scrambles” cam (or, in the East, the TriCor “Daytona” cam) used by Gary Nixon in his 500-cc flattrackers, the Q-type cam can be described as moderately sporty, with 269 degrees duration. Intake opens 34 btc, closes 55 abc. Lift is .314 in. By comparison, the flattracker cam has only 8 degrees more duration and .313-in. lift. The N-type profile is used in the T100C exhaust cam mainly to shorten intake/exhaust overlap, i.e., the time both intake and exhaust valves are open simultaneously. Shorter overlap makes the engine more useful at lower rpm for off-road riding.

Duration of the N-type cam is shorter, at 255 degrees, with exhaust opening at 48 degrees bbc and closing 27 degrees ate. Lift is also milder at .296 in. Comparing overlap of the two TIOOs is useful: in the R, where two Q-type cams are used, overlap is 68 degrees; in the C model, utilizing Q intake and N exhaust, it is 51 degrees.

Triumph cam faces in the past have not been noted for extreme longevity, but the situation has greatly improved since the manufacturers adopted a nitriding process to harden the cam lobes in 1969.

Some TIOOs may exhibit a slight tluftiness or lag just before the upper power band is reached, as did our test machine. This has nothing to do with the cam design, but is caused by the Amal Concentric carburetor running slightly rich. Reducing main jet size slightly or dropping the needle a position will eliminate the lag effect.

While the TIOOs have not undergone any major design changes since the appearance of the unit transmission, they are regularly improved, the changes rarely being announced. Most recently, to reduce wear, the timing side of the crankshaft has been converted to run on ball bearings, as do the 650s, rather than plain bearings. The drive side now runs on roller bearings. Lubrication is now similar to the 650s: oil is pumped to the crankshaft timing side by use of a disc in the timing cover, and exits through two holes in each journal to lubricate the big ends, which ride on plain bearing inserts. There is no bushing on the small end of the rod.

The crankcase breathing system used on the Daytona racers is now standard production practice in the T100C. Rather than employing the usual timed breather, the crankcase vents to the primary chaincase. This is accomplished by eliminating the oil seal on the drive side main bearing, allowing air pressure and oil mist to vent through the bearings to the chaincase. Three 1/16-inch holes in the crankshaft chamber wail allow excess oil to dribble back from the chaincase to the sump.

An important benefit of this system is that the primary chaincase can never run dry; proper oil level is automatically maintained. This is rather clever engineering when you think about it. Eliminate the expense of two parts, oil seal and breather, and gain a simple form of automatic oiling at the same time.

Another area of minor improvement is in the transmission, which has always been one of the T 100’s strongest points in terms of lightness and smoothness. Gas carburizing is used to harden transmission gears, resulting not only in longer life, but quieter running. Why the gears should run quieter is not immediately apparent, but the hardening process does result in a smoother finish on mating surfaces, which would make for quieter meshing.

As for chassis and suspension, they benefit from several improvements in recent years. In 1967, the diameter of the front down tube was increased for greater strength and the fork rake increased 1 degree, both useful for dirt application. At this time, the swinging arm was beefed up after experimentation with the Daytona racers. These improvements are greatly responsible for the 500’s stability on the road and its precise steering. The springing at the rear is just about perfect for road riding, but acts somewhat spongy if you hang slides on your favorite fireroad. Chances are that stripping the bike for the dirt, which will bring the machine down to about 330 lb., would have the effect of making springing more properly stiff.

The front forks are excellent, damp well, and contribute much to the bike’s good handling. On the 1970 model, the practice of finishing-grinding and chroming the stanchions has been added, to improve the function of the oil seals. Dirt riders will welcome the wider handlebars, the same as those on the 650s, replacing the narrow bars of yore which were usually the first item a T100 owner would unload.

While we’re at it, here are a few other 1970 detail improvements: carburetor mounted on a rubber O-ring to prevent fuel frothing; a better air filter, four-ply instead of two; adjustable sidestand folding to allow hard leaning types to get it up out of the way; easier access to rear damper adjustment holes; mirror bracket mounting integral with hand lever assemblies.

While never-ending refinement such as this has made the T100 Triumph’s finest achievement, you wonder whether they haven’t forgotten something. The problem is rather akin to the evolution of the old Leica. It started out light and compact. You could put it in your pocket. That was its virtue. But it got heavier, and bigger. Nowadays, nobody sticks a Leica M4 in his pocket.

Likewise, The T100C has gained about 20 lb. in the last few years. Before that, it was even lighter. Some of the weight comes from the second muffler; add a few ounces for the flimsy trellis which guards milady’s leg. Frankly, we would rather burn milady’s leg, but fortunately for her, we are not in the majority. The second muffler, of course, provides the required degree of silent legality, while retaining exhaust efficiency. But it would be nice to see development of a single, lighter silencer that could do the same thing.

Aiming closer to the 300-lb. mark would serve to better differentiate the 500 from the 650. This, plus the addition of a five-speed gearbox, would serve to increase the appeal of both C and R models beyond the devoted coterie of road riding purists and four-stroke trail buffs who now comprise the bulk of its market.

As it is, the T100C is poetry. Superb road handling. A modicum of convertibility for the dirt. Excellent braking, requiring only one or two fingers on the front stopper. Easy starting. And exemplary reliability. But in terms of development, the T100 is at the same stage as the Austin-Healey sports car (although it’s a darn sight better than the Healey will ever be). Both have been refined so conservatively, that they are on the verge of extinction.

Simply, we’d like to see the 500 evolve. And thereby endure. We can see its virtues, tangible and intangible. But can the mass market see? They are not so devoted as we are.

TRIUMPH TROPHY 500

$1160

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

February 1970 -

Features

FeaturesNight Rider

February 1970 By Stuart Munro -

Features

FeaturesHow To Teach Your Girl To Ride

February 1970 By David C. Hon -

Special Color Feature

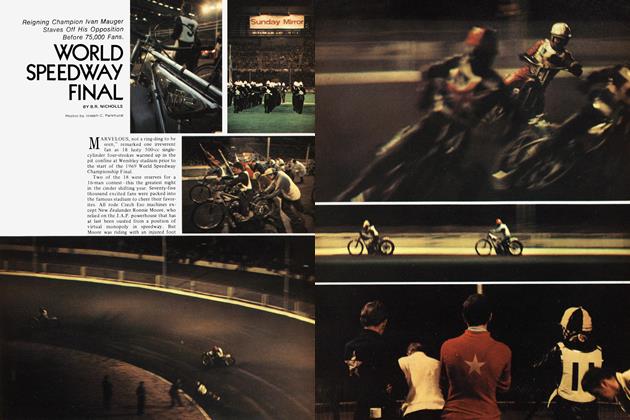

Special Color FeatureWorld Speedway Final

February 1970 By B.R. Nicholls