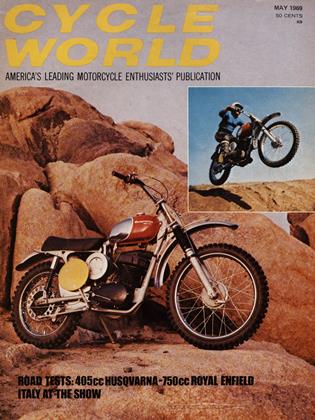

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

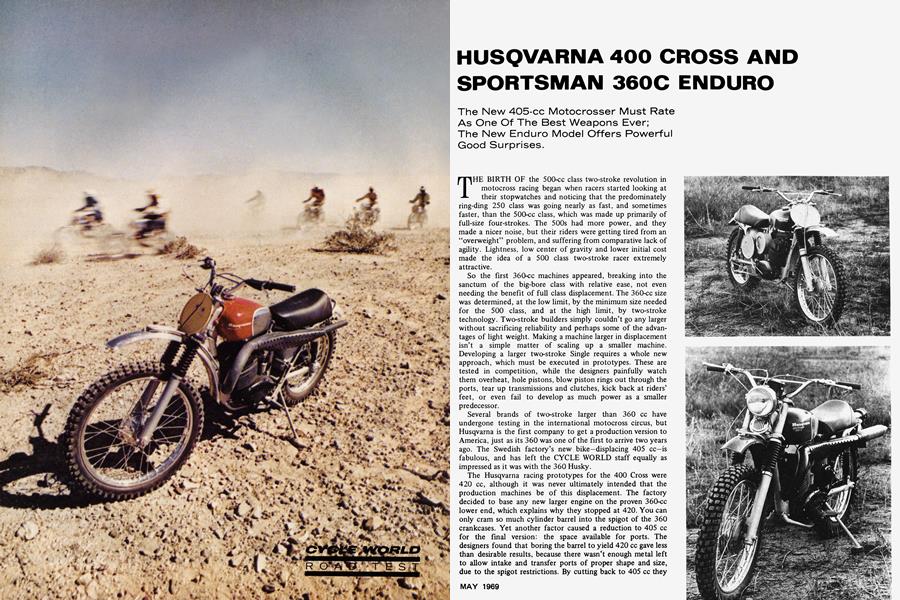

HUSQVARNA 400 CROSS AND SPORTSMAN 360C ENDURO

The New 405-cc Motocrosser Must Rate As One Of The Best Weapons Ever; The New Enduro Model Offers Powerful Good Surprises.

THE BIRTH OF the 500-cc class two-stroke revolution in motocross racing began when racers started looking at their stopwatches and noticing that the predominately ring-ding 250 class was going nearly as fast, and sometimes faster, than the 500-cc class, which was made up primarily of full-size four-strokes. The 500s had more power, and they made a nicer noise, but their riders were getting tired from an "overweight" problem, and suffering from comparative lack of agility. Lightness, low center of gravity and lower initial cost made the idea of a 500 class two-stroke racer extremely attractive.

So the First 360-cc machines appeared, breaking into the sanctum of the big-bore class with relative ease, not even needing the benefit of full class displacement. The 360-cc size was determined, at the low limit, by the minimum size needed for the 500 class, and at the high limit, by two-stroke technology. Two-stroke builders simply couldn’t go any larger without sacrificing reliability and perhaps some of the advantages of light weight. Making a machine larger in displacement isn’t a simple matter of scaling up a smaller machine. Developing a larger two-stroke Single requires a whole new approach, which must be executed in prototypes. These are tested in competition, while the designers painfully watch them overheat, hole pistons, blow piston rings out through the ports, tear up transmissions and clutches, kick back at riders’ feet, or even fail to develop as much power as a smaller predecessor.

Several brands of two-stroke larger than 360 cc have undergone testing in the international motocross circus, but Husqvarna is the first company to get a production version to America, just as its 360 was one of the first to arrive two years ago. The Swedish factory’s new bike—displacing 405 cc—is fabulous, and has left the CYCLE WORLD staff equally as impressed as it was with the 360 Husky.

The Husqvarna racing prototypes for the 400 Cross were 420 cc, although it was never ultimately intended that the production machines be of this displacement. The factory decided to base any new larger engine on the proven 360-cc lower end, which explains why they stopped at 420. You can only cram so much cylinder barrel into the spigot of the 360 crankcases. Yet another factor caused a reduction to 405 cc for the final version: the space available for ports. The designers found that boring the barrel to yield 420 cc gave less than desirable results, because there wasn’t enough metal left to allow intake and transfer ports of proper shape and size, due to the spigot restrictions. By cutting back to 405 cc they solved this problem. As a result, the 405 actually produces 5 more bhp at peak revs than did the original 420. The cylinder barrel with cast iron liner, incidentally, is a completely new item, rather than being reworked from the 360.

It is worth noting that the Husky two-stroke Singles have been of seven-port design (including exhaust) all along, although other manufacturers have made more noise about their own seven-port designs. In the Husky, these ports include three transfer ports, a central intake port, two branched intake ports and the exhaust port.

The head is newly created for the 405, and features an unusual interruption of finning at the point where it meets the cylinder barrel, to aid cooling by keeping heat from moving into the head from the cylinder barrel. Further assistance is provided by downward pointing 0.187-in. fins emanating from the lowest horizontal fin on the head. The larger piston was thoroughly tested for stress in the 420s which competed in the Inter-Am motocross series last winter. Sealing is provided by two narrow chrome rings. Bore is 81.5 mm. A new crankshaft increases the stroke to 76 mm.

To cope with the extra power, Husqvarna has strengthened the transmission with a larger mainshaft and taper. The countershaft sprocket is mounted directly on the taper, without the use of a key or spline. Primary reason for this arrangement is to facilitate a change of gear ratios to best suit the circuit being raced. Rather than fiddle with cumbersome and annoying rear wheel sprocket changes, or, for that matter, only relatively less bothersome changes to the traditional splined countershaft sprocket, the Husky allows easier substitution of countershaft sprockets. The sprocket is quickly snapped off with the aid of a special pulling tool. Husqvarna provides a number of sprockets ranging from 11 to 17 teeth, and the puller, with the newly purchased machine.

Retained from the previous Husqvarna dirt racers is the floating rear brake, the drum of which is anchored by a strut to the frame cradle instead of the swinging arm, to provide even stopping action over bumpy surfaces. The rear wheel assembly has been improved with a larger spindle and sealed bearings. For easier lubrication, there is now a grease nipple on the rear brake cam spindle.

The two most notable things that strike the rider about the Cross are its readiness to start, and its broad, smooth power band. Starting demands a determined kick, as might be expected from a big two-stroke Single with 10.5:1 compression ratio. The task isn’t helped any by the kickstarter, which is short and doesn’t engage fully at the top of the stroke to allow a full swing on the lever. Nonetheless, the machine comes to life quickly after one or two attempts and is rarely given to kicking back.

The solid, low-rpm torque and smooth power band running all the way to 9000-9500 rpm offer convincing proof of the benefits of increased displacement. The Husky has no tendency to lunge suddenly in the middle of acceleration. Hence the worries are less about over-aviating the front wheel, and directional control out of tight turns is much improved over that of the 360.

The 400 Cross chassis is quite similar to that of the 360, with massive single downtube and downward curving maintube. But the front downtube forks into two smaller cradle tubes, which tie directly into the rear frame supporting members. This provides a more rigid mount for the inboard mounted swinging arm pivot. The front forks are as before, but travel has been increased to a claimed 8 in. They seem greatly improved, having excellent double damping, and provide a much softer ride in the rough. The wheelbase is 0.7 in. longer than before, which may be the reason that the bike seems more stable than its predecessor.

Steering is still a bit quick, and it requires constant concentration, compared to machines with longer wheelbase. But, the relative shortness makes the Husky quick in the tight stuff and a cinch to lay over as far as the rider dares. Combine that with roto-rooter torque characteristics and you have what amounts to one of the best handling motocross machines available.

We had only to take the quickest glance at the new Sportsman 360C Enduro to conclude that it was strictly business. It has lights, horn, dual battery/direct lighting and barely enough muffler to make it “legal” under the scrutiny of a benevolent feeling highway fuzz. But it won’t suit the sometimes dubious requirements of the average American trail rider. The Sportsman has about as much frill as a Browning Automatic Rifle. Good thing, this functionality, for the rather steep purchase price is buying something more useful than dead weight, chrome plate and wierdo blinker pods.

The 360C (C for competition) is a motocross machine in disguise, and undoubtedly will find its way into many a high speed cross-country race, as well as standard time enduros. The gearbox ratios are spread wider apart than a motocrosser’s, so that first gear can take on anything, yet high gear reaches out for 90 mph. This combination is particularly suitable for desert racing and Baja type events.

The Sportman’s engine displaces 360 cc, putting it in the 500 class, and except for minor differences is virtually the same as Husky’s 360-cc Motocross. Compression is a mild 8.5:1, but the cylinder barrel is exactly the same as the 360 racing machine.

Frame configuration is along the old 360 Unes. The large downtube forks at the front of the cases into two smaller tubes which remain fairly close together as they run underneath the engine to tie in with the swinging arm assembly, rather than connecting with the rear frame members as they do on the 400. Evidence that the bike is intended for desert roughery comes in the form of a bash plate. The wheelbase, at 54.7 in., is slightly longer than the motocross bike, but much shorter than Husky’s previous enduro bike, the Commando, which stretched out past 57 in. As with all of the 1969 Husqvarna line, the 360C is blessed with the new, longer travel forks.

A handsome rubber-cushioned trip-set VDO speedometer/ odometer unit completes the enduro picture. The dial and numbers are big enough to provide easy reading at any time, even if the cursing pilot’s eyes are red from mud and rain. The two-circuit lighting system, which at the flick of a switch draws power from the battery to comply with the laws in several states for street bikes, or direct from the alternator should the battery become disabled, is also a welcome touch. A large 4.2-gal. fuel tank allows the necessary long-distance range between gas stops needed for this type of machine.

Handling is definitely “dirt bike” in quality and no compromises have been made for street riding. (In fact, we wonder why any manufacturer should compromise the geometry and suspension of any fullor even half-time dirt machine. Any bike with proper rough-terrain geometry will handle well enough on hard pavement, while most compromise machines prove a handful to ride in the dirt, if not downright dangerous.) The Sportsman weighs only 253.5 lb. with all its extra equipment, and therefore is manageable in any situation.

The great deal of power available at the flick of the throttle -the most we have encountered in any comparable enduro machine-would be surprising were it not for the large amount of noise coming from the bike’s ineffectively disguised expansion chamber. Riding the Sportsman through a quiet residential district would border on law-baiting.

But the noise is of no real worry. The rider of a 360C is bound to be a super-enthusiast who will truck his bike out to the sticks where people aren’t so uptight, or just aren’t. And that is much of the charm of cross-country racing. jo]

HUSQVARNA 400 CROSS

$1249

SPORTSMAN 360C ENDURO

$1089

SPECIFICATION

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

Round UpRound Up

May 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

The Service DepartmentThe Service Department

May 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1969 -

The Scene

The SceneThe Scene

May 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Travel

TravelSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

May 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

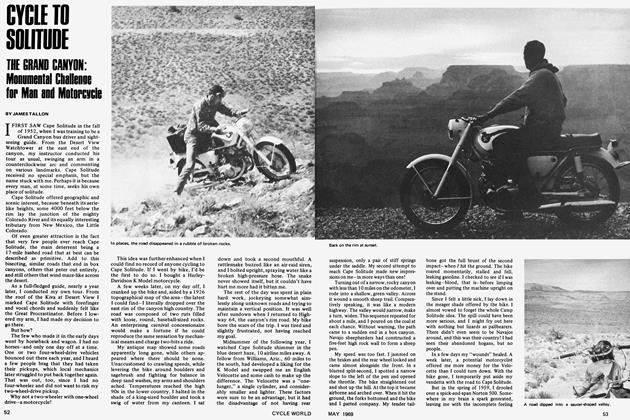

Travel

TravelCycle To Solitude

May 1969 By James Tallon